This is a follow-up to a recent post in which I suggested we return to simply enjoying food instead of worrying about it. Our “toxins are everywhere” culture seems to be presently engaged in making us super-anxious about what we eat and drink: “Five Foods You Should Never Eat,” “Your Doctor NEVER Eats This,” and similar ominous warnings appear to be a permanent fixtures on web pages and magazine covers these days.

My bottom line was, What you eat probably won’t kill you/what you don’t eat probably won’t cure you. One exception to this simplistic comment is celiac disease. If you have it, gluten may not kill you, but it sure will hurt you, by damaging the inner brushlike surface of your small intestine. Celiac disease affects somewhere between 1 in 100 and 1 in 200 of the population; a blood test with a follow-biopsy can establish if you have it.

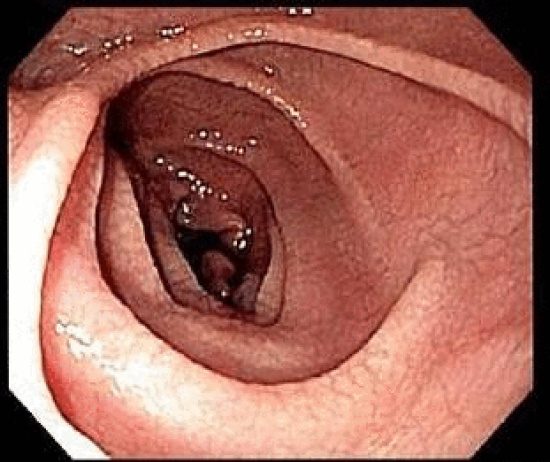

Scalloping and “caked mud” appearance of damaged lining of small intestine caused by celiac disease. [“Samir at en.wikipedia.” Creative Commons Attribution.]

Celiac disease is, for hotly-debated reasons, about five times as common as it was 30 years ago. Other immune disorders such as hay fever, IBS and multiple sclerosis are also on the rise, suggesting that our intestinal microbial communities are getting more compromised, perhaps by overuse of antibiotics and too much emphasis on hygiene.*

Here’s a little more on gluten. It’s a protein, created when molecules of glutenin and gliadin combine during the production of flour by milling. The gluten emerges from the mixture as an elastic membrane—it’s what makes bread chewy and pizza doughy. Bakers sometimes add “vital wheat gluten” to dough to trap carbon dioxide and add volume to bread, and it’s added to pasta, cereal, crackers and literally hundreds of foods as a thickener.

Wheat provides 20 percent of the world’s nourishment. [“Bluemoose.” GNU Free Documentation License]

Gluten is found in wheat, rye and barley, meaning that it’s ubiquitous. Wheat, for instance, provides about one fifth of the world’s calories (more nourishment that any other source), equivalent to about 200 pounds per human per year. It’s easy to grow, easy to store and easy to ship. Wheat and wheat derivatives are found in about one third of foods stocked in a typical U.S. supermarket.

Gluten appears to be one of the four basic food needs (the others are salt, sugar and fat) that humans adapted to long ago; cut out one, and your body (or the food manufacturer!) will try to compensate by providing more of the others. That’s one reason why diets are, in general, so difficult to maintain: our stomachs are far better at manipulating our brains than the other way around. (As I wrote recently in the Journal, “…will power isn’t the issue. You’re not a weak, bad person if you go off the diet wagon. You’re a normal person, with normal genes, and a body that outsmarts your brain.”)

The jury is still out on Non-Celiac Gluten Disease, or NCGD, but meanwhile, if you’re having symptoms, it’s worth trying to find out if you really are allergic to gluten — if only because it’s such a hassle to completely cut it out completely from your diet! Also, because there’s a genetic component to the disease, your blood relatives may end up thanking you.

* One piece of supporting evidence for the “too much hygiene” idea comes from Karelia, the territory that spans the border of Russia and Finland (the area has a sad, complicated history). Although the populations on both sides eat similar amounts of wheat, celiac disease—together with allergies and asthma – is up to five times more common on the Finnish side. Why? The theory is that Russian Karelia, being poorer, is less attuned to hygiene, so suffers a higher incidence of fecal infections, which result — ironically — in stronger immune systems.

The closest I got to Karelia: Savonlinna Castle, Finland. [Barry Evans]

CLICK TO MANAGE