A 9.5-megawatt floating wind turbine deployed at the Kincardine Offshore Wind project, located off the coast of Aberdeen, Scotland. Photo: Principle Power.

###

The wind resource beyond Humboldt Bay is among the best in the United States, with strong, consistent wind speeds that are ideal for commercial development. There’s just one problem: electrical transmission.

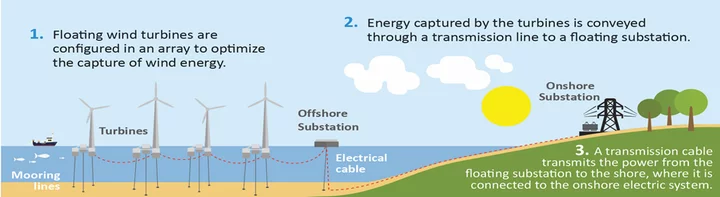

Getting the power from the floating offshore turbines to the shore is one thing; getting the power to communities throughout the region and across the state is another. Wind developers can run big, subsea cables from their offshore wind projects to land with relative ease, but once that power comes ashore it encounters an electrical grid that wasn’t designed to handle it.

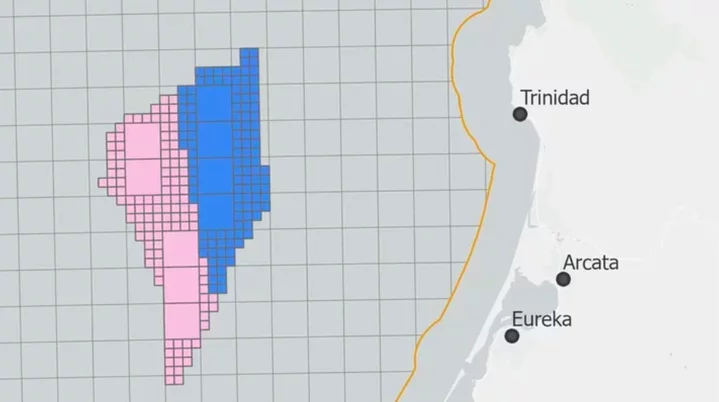

Image: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM)

The Humboldt Wind Energy Area (WEA), located approximately 20 miles west of Eureka, will host as many as 100 floating wind turbines across 200 square miles of deep ocean waters. The Humboldt WEA will capture a mere fraction of the state’s renewable energy potential. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates the state’s offshore winds “have the technical potential to produce … approximately 150 percent of California’s annual electricity load.”

The problem is, local capacity is extremely limited, and the North Coast region is relatively isolated from California’s electrical load centers. As you can see in the map below, there are only a handful of transmission lines running in and out of Humboldt County, none of which have the capacity to accommodate the power generated by a commercial offshore wind development.

California’s power grid. Thicker lines = higher capacity transmission. Zoom in for greater detail. Data: California Energy Commission.

Matthew Marshall, executive director of Redwood Coast Energy Authority (RCEA), likened the state’s electrical transmission system to a network of roads, offramps and highways. The highways, or bigger transmission lines, can carry more electricity.

“Here in Humboldt, we’ve got little two-lane, winding roads like State Route 36 going in and out of the county, but what we need is, like, Interstate 5 through Los Angeles, because the potential for power generation is at a state level of significance,” Marshall explained. “It’s an exciting opportunity for us, not only to meet our own climate goals but to be an exporter of clean power and to help further the state’s goals. It’s going to be a huge undertaking, not to just build the wind farms but to also build up the infrastructure needed to handle the power being generated.”

In fact, parts of the county are already at capacity. Late last year, Pacific Gas and Electric informed the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors that it had all but reached its limits to transmit electricity to new projects throughout the Eel River Valley and Southern Humboldt.

“That line that travels south through the county is very small and it needs upgrades to provide more service,” Marshall said. “When we look at offshore wind and the scale of our energy use here, there is no way our existing infrastructure can accommodate the energy the offshore wind farm will produce. Our local energy demand is, like, 10 percent of what the Humboldt [WEA] could generate.”

Upgrading the line from 60 kilovolts (kV) to 115 kV would alleviate existing transmission limitations, said Arne Jacobson, executive director of the Schatz Energy and Research Center at Cal Poly Humboldt, “but it won’t be big enough for what is required for large-scale offshore wind development.”

“There are basically three state agencies involved in the energy transmission aspect of offshore wind: the California Energy Commission (CEC), the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) and the California Independent System Operator (CAISO),” Jacobson explained.“The CPUC issued a decision at the end of February to order reliability procurements. Essentially what it’s doing is ordering the CAISO to develop transmission lines for offshore wind.”

CAISO, the entity that manages the flow of electricity on high-voltage powerlines and oversees infrastructure planning across the state, estimates the total cost of transmission development over the next 20 years – including transmission line and substation upgrades across the state – to clock in at a staggering $30.5 billion.

The report, 20-Year Transmission Outlook, notes that some existing transmission lines could be used for the Morro Bay WEA but the North Coast area will need “significant” upgrades to integrate offshore wind into the state’s grid.

“To facilitate the interconnection of the 4,000 MW of offshore wind in the North Coast to the ISO system, the ISO identified the need for two 500 kV [alternating current] lines connecting to the Fern Road 500 kV substation and a [high-voltage direct current] line to the Collinsville 500/230 kV substation,” the report states. “One other alternative considered in the ISO’s 2021-2022 Transmission Plan is a … deep sea cable to a new station referred to as Bay-hub located in the Greater Bay Area.”

In simpler terms, the state could increase capacity by upgrading the main transmission lines for the region – one coming in from Cottonwood to the east and the other from Laytonville to the south – or connect directly to the San Francisco Bay Area via subsea cable.

“We’re probably going to need two out of those three options to accommodate the power that will be generated by the offshore wind farm,” Marshall said. “There are other options, like, what if we went up to Oregon instead? Wind energy areas are being developed for Oregon as well. Whether we connect to a larger western grid of the California grid is definitely not decided yet. It’s probably a 10-year process between planning and permitting and then, eventually, construction.”

The future sit of the Humboldt Wind Energy Area. Map: BOEM

Another report, Transmission Opportunities for California North Coast Offshore Wind, Vol. 1: Executive Summary conducted by the folks at the Schatz Center, explores options for offshore wind development that fit within the bounds of the region’s existing transmission infrastructure. However, the study notes that “developing an economically viable offshore wind project at a small scale is challenging.” The alternatives identified in the study were projected to have financial losses over the project’s lifetime.

“While the wind resource could enable [the] development of large-scale wind farms, the existing transmission infrastructure limits the size of projects in the absence of significant investment in transmission upgrades,” according to the report. “An initial option for [the] establishment of an offshore wind industry in the region could involve [the] development of one or more small commercial wind projects that are scaled to match local loads and transmission capacity, requiring only modest investments in new transmission infrastructure.”

Marshall spoke in favor scaled approach because it would prioritize local energy needs.

“I think there’s a lot of that’s a desirable outcome to meet our local goals and potentially hit those targets for clean, renewable energy sooner rather than later,” he said. “Doing it that way, we can also learn and make sure there aren’t unanticipated environmental impacts. … But, even if it’s not entirely done in phases, the developers can’t just snap their fingers and suddenly there are a hundred turbines in the ocean. There’s going to have to be a sequential deployment because it will take a while to get the projects fully built out because of the sheer size and scale of the effort.”

Even so, state and federal lawmakers are trying to expedite the process.

“This is going to take many years,” Rep. Jared Huffman told the Outpost in a recent phone interview. “Anyone who thinks that we are very close to manufacturing these huge turbines, getting the clean power onto the grid and adding these thousands of jobs might be disappointed. This is going to take close to a decade to really bring it all forward, but I’m hoping we can speed that up.”

However, the development of offshore wind is completely dependent on California’s transmission capabilities. Those issues must be resolved before offshore wind can move forward, Huffman said.

“The developers don’t know how many of these floating platforms they’ll even be able to install until they know whether there’s enough transmission to move the power onto the grid,” he continued. “To me, that’s by far the most important bottleneck here. Until you have all that figured out, you really don’t know a lot about the economics of the project. When you’re trying to negotiate community benefits and other things, you can begin those conversations now, but you can’t sign on the dotted line until you know how big the project is, how much it’s going to cost, how profitable it’s going to be. It all depends on all of these details that tie back to questions about transmission.”

There are several bills moving through the California legislature that would ease the implementation of offshore wind and electrical transmission efforts across the state, including AB 3, AB 50, AB 80, AB 344, SB 286 and SB 319.

AB 50, introduced by Assemblyman Jim Wood, would ensure that large electric corporations adhere to electric connectivity timeframes.

“We can’t reach our housing and climate goals and expand local economies if utility companies can’t meet the demand for electricity when it is required,” Wood said. “My bill, AB 50, looks to improve the planning process for meeting the state’s electrification goals, which will be crucial in ensuring the North Coast has the infrastructure to support the development of offshore wind farms as well as to meeting California’s critical housing and climate goals.”

Similarly, state Senator Mike McGuire’s bill, SB 319, would implement “a long-term fix-it plan for [PG&E’s] antiquated system.”

“PG&E has been underinvesting in their infrastructure for decades, putting profits over people, and our communities are paying the price. This simply can’t stand,” McGuire wrote in an emailed statement. “That’s why we’re advancing critical legislation, SB 319, that would force PG&E to do their actual damn job connecting homes, businesses and green power projects with safe and reliable distribution and transmission lines.”

Marshall added that RCEA will continue to engage at the regulatory level to advocate for local interests.

“We want to make sure [this project] doesn’t end up just being a flyover situation where they build the wind farms and build a giant 500-kV line that just takes the power straight from the ocean and down to the Bay Area,” he said. “That would be the worst-case scenario. … To use my road analogy, it would be a shame if this brand-new highway doesn’t have any off-ramps. Hopefully, there will be local benefits as well as an investment in our community infrastructure and power grid. That would be a win-win.”

[CORRECTION: This post originally stated that the Humboldt WEA could potentially produce more than 150 percent of the state’s current demand for electricity. It has been corrected. The Outpost regrets this error.]

###

DOCUMENT: Transmission Alternatives for California North Coast Offshore Wind: Volume 1 Executive Summary

PREVIOUSLY:

- Biden Administration Proposes Offshore Wind Lease Sale, Including Two Spots Off the Humboldt County Coast

- IT’S ON: Humboldt Offshore Wind Leases to Go Up For Auction on Dec. 6

- Harbor District Announces Massive Offshore Wind Partnership; Project Would Lead to an 86-Acre Redevelopment of Old Pulp Mill Site

- Offshore Wind is Coming to the North Coast. What’s in it For Humboldt?

- North Coast Fishermen Fear for the Future of Commercial Fisheries as Offshore Wind Efforts Advance

- North Coast Tribes Advocate for ‘Meaningful, Impactful Partnership’ with Potential Developers Ahead of Tomorrow’s Highly Anticipated Offshore Wind Lease Auction

- ‘Together We Can Shape Offshore Wind for the West Coast’: Local Officials, Huffman and Others Join Harbor District Officials in Celebrating Partnership Agreement With Crowley Wind Services

- SOLD! BOEM Names California North Floating and RWE Offshore Wind Holdings as Provisional Winners of Two Offshore Wind Leases Off the Humboldt Coast

- ‘It’s Beyond Frustrating’: Yurok Vice-Chair Calls Out Provisional Winners of Offshore Wind Bid for Failing to Engage With the Tribe Aheads of This Week’s Auction

CLICK TO MANAGE