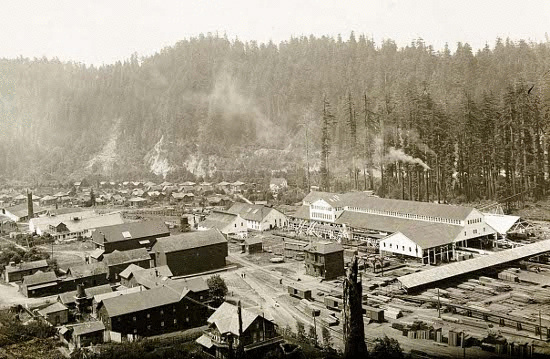

Once upon a time, the company town of Scotia – all the houses, all the commercial buildings, the post office, the Winema Theatre, the Scotia Inn and the factory itself – was heated with steam. The Pacific Lumber Company’s biomass plant burned wastewood from its massive milling operations to generate electricity and boil water for a strange village-wide network of underground tunnels and pipes. On cold days these pipes blew hot steam into hundreds of radiators, warming a grateful workforce. The service was provided free of charge.

Like so much else in Scotia, this is very nearly a thing of the past. Pacific Lumber is bankrupt and gone. The Humboldt Redwood Company now owns Scotia’s remaining mill. Its civic and commercial buildings and all its houses are owned by an entity called Town of Scotia. The building that houses Stanwood A. Murphy Elementary School was sold off to the school district, and, most recently, the biomass plant was picked up by a Sacramento firm called Greenleaf Power.

These latter organizations – once both arms of the same corporation’s benevolent dictatorship, now independent actors swimming in the chaos of the Palco Perestroika – have been in a bit of a struggle these last few weeks. That’s when Greenleaf gave Scotia Elementary, which seems to be the last facility in town to depend, in part, on the old ways of doing things, a final deadline: Wean yourself from company steam by March 1, or else go cold.

Greenleaf now plans to shut down its entire plant for a couple of months to repair and retool its biomass plant. Soon, energy that used to heat the town will be captured and sent to the electrical grid. Steam delivery will be gone for good. The company’s deadline put Scotia Elementary in a tough spot. Some of the school’s facilities have already been converted, but the pool, the gymnasium and four classrooms are still on steam. Would the stoppage close school?

Happily, it appears that it will not. The school board met last night and approved the emergency purchase of a $66,000 device that will allow Scotia Elementary to produce its own steam, enough to heat the four remaining classrooms. The gymnasium and the pool will have to be shut down for at least several months while the school board and the community find a new way to heat those facilities.

Town of Scotia President Frank Bacik sympathized, somewhat, when the Lost Coast Outpost spoke with him earlier today. He said that the town stood ready to offer alternatives sites for classes while the school undertook the needed renovations. Still, he found it hard to muster much personal compassion for the plight of the people running things at the school district.

“They’ve known for years that the free steam from the power plant would eventually end, and that every building needed to convert to PG&E,” Bacik said. “Only the school has failed to complete that conversion.” He fowarded his correspondence with Scotia Superintendent Jaenelle Lampp dating back to 2009, which warns the school of the need to seek alternative sources of heat.

Lampp, reached a few hours later, didn’t at all deny that Scotia Elementary has been well aware of the impending end of steam service. The injunction to seek alternate heating options was written into the school district’s contract to purchase the facility after the collapse of Pacific Lumber, she said. But the State of California’s fiscal crisis has starved the particular pool of funds that finances plant improvement projects of this sort. The California Office of Public School Construction has pledged some $900,000 to modernize the school’s heating system, Lampp told the Lost Coast Outpost, but the district has only received $189,000 so far.

Part of that money will now be used to purchase the small boiler that will keep the remaining steam-powered classrooms open. Now it’s all hustle to get the thing up and running before deadline. Everyone’s pitching in. Lampp said that Greenleaf has pledged to fudge the shutoff by a couple of days if that will help, for which she was very grateful.

“Everyone’s doing everything possible to race through this as fast as we can,” Lampp said. “Worst case scenario? We could have school closure days.”

Unfortunately, things don’t look so good for the gymnasium. The district will have to shutter the facility at least until the state delivers the balance of funds it has pledged, Lampp said. Without heat, she fears that mold and decay will set in.

But she had reason to be hopeful. The entire community uses the gymnasium, and various community groups are trying to find other grant funds that might pitch in. A nonprofit group that advocates for public pools wants to help the district reheat the pool, somehow. In these endeavors, which are long-term and whose paths to success are not entirely clear, the school district has to pray that Scotia’s civic spirit is longer-lived than the big corporation that once bankrolled it.

CLICK TO MANAGE