Welcome to the freshly constructed LoCO Coliseum! I’m your announcer Andrew Goff! Today, your Lost Coast Outpost launches a new feature … LoCO Infight! in which office disputes concerning issues that affect our community are waged in front of the bloodthirsty Humboldt multitude. Are you ready to rumble?

Let’s do this! The topic for our first online slobberknocker: Should Humboldt County ban the production of genetically modified organisms? Discussion surrounding this particular query arose due to the fact that local activists with the group GMO Free Humboldt are currently pounding the pavement for signatures with the hope of getting an initiative placed on this year’s ballot that would prohibit the cultivation and production of GMOs in Humboldt County.

Let’s do this! The topic for our first online slobberknocker: Should Humboldt County ban the production of genetically modified organisms? Discussion surrounding this particular query arose due to the fact that local activists with the group GMO Free Humboldt are currently pounding the pavement for signatures with the hope of getting an initiative placed on this year’s ballot that would prohibit the cultivation and production of GMOs in Humboldt County.

Your inaugural LoCO Infight combatants will be Hank Sims, arguing for local GMO production prohibition in the piece below, and Ryan Burns, arguing against such a ban in this opposing screed. It should be noted that your gladiators were not granted knowledge of the other’s attack strategy prior to clicking “Publish.” We want a fair fight.

Now, please enjoy the spectacle of co-workers bludgeoning each other on the blogosphere field of battle. This, is LoCO Infight. -AG

# # # # #

Ten years after the flame-out of Measure M on a technicality, Humboldt County residents are taking another stab at an ordinance banning the cultivation of genetically modified organisms within our borders. Petitioners are out gathering signatures for the so-called “Humboldt County Genetic Contamination Prevention Ordinance” – read the text of it here, along with impartial analysis here – with the hope of qualifying it for the local ballot.

This is a long time in coming, considering that Humboldt County is generally skeptical of GMOs. A year and a half ago, we overwhelmingly voted in favor of Proposition 37, which would have required statewide labeling of genetically modified products. The new measure will almost certainly reach the ballot, and it will almost certainly pass.

Unlike other writers I could name, I applaud the good sense of the people of Humboldt County in this matter. In point of fact, the measure is not only in the county’s immediate best interest – it is in the interest of all people, in that it lends the county’s little voice to the sensible argument that perhaps we should not so quickly rewrite blueprints of life that we barely understand.

The simplest and most immediate argument in favor of the measure is that it would be good for our economy. For some time, the county’s business community – and especially its agricultural community – has been pushing, in concert, to make the words “Humboldt County” synonymous with everything clean, wholesome and natural in the mind of the average consumer. Why? Not least because it allows those companies to sell their products at premium prices – an absolute necessity if those industries are to survive and thrive in our far-flung, terrain-challenged, transportation-poor county. Go take a gander at the websites of companies like Eel River Beef or Humboldt Grassfed Beef or the Humboldt Creamery, all of which are located in the county’s most politically conservative region. What key words and phrases do you note? “Organic,” “natural,” “humane,” “pristine,” “pasture-raised,” “local family farms,” and – in Eel River’s case – “GMO-free.”

The owners of these businesses are not dummies. Neither are they raving hyper-radical leftwing freaks. They see a niche in the market and they are working to fill it in a way that their competitors have not or cannot, and their products are bringing big dollars into this community from the outside. Livestock and dairy accounted for $117 million of Humboldt County’s gross domestic product in 2012 – the very large majority of the county’s non-timber, non-marijuana agricultural earnings. Put them head-to-head with Cargill and they are dead. They have to distinguish themselves from the cheap stuff if they want to justify higher prices, and they’re doing just that – kind of miraculously, actually.

(Note that when agribiz giant Foster Farms acquired Humboldt Creamery in 2009 – not the dairy farms, but the Creamery that buys milk from the farms – it kept the Humboldt label alive and now actively promotes it as a high-end line.)

A local GMO ban would support these vital local industries by underlining their branding efforts and capping them with an exclamation point. We can say to their customers: Hey, that stuff our businesses have been telling you? That is correct. Humboldt County is all about quality, non-corporate agriculture. We believe in local family farms. We are organic and natural and humane and pristine.

What would we lose in so doing? Very, very little. At present, it seems that the only GMO crop ever to have been commercially grown in Humboldt County is corn, for silage purposes. It’s unclear whether anyone is growing it now. And guess what? Since almost all of Humboldt County raises its cattle on grass pasture and labels it as such, there isn’t much of a local market even if anyone did wish to hop in. And cattlemen who wish (wisely) to shoot for the “USDA Organic” seal on their meat or milk can’t use GMO feed for their herd, anyway.

So that’s the easy case. A Humboldt County GMO ban would have next to zero economic downside and a very positive economic benefit, in that it supports the work our local farmers have already been doing in marketing the county’s agricultural operations to consumers outside the area – those who want fresh, natural, organic, non-GMO-tainted food and are willing to pay top dollar for it.

Now, you could say, as my estimable colleague no doubt will, that these consumers are fools. No one has ever demonstrated that eating transgenetically engineered food has any ill health effects at all. By playing into their fears of GMOs, we flatter and encourage their knuckleheaded distrust of new, beneficial technologies.

One might crassly respond to this with a shrug of the shoulders: So? Unless capitalism suddenly grew a conscience overnight, there are far worse ways to fleece the suckers than by offering them the chance to buy the food that their grandparents ate, before it was redesigned in a laboratory.

For myself, though, I don’t believe that GMO skeptics need be so amoral. Neither do I believe they need to trumpet every last scrap of Internet paranoia about the technology to make their case. I don’t believe that producers and consumers who seek to slow the adoption of genetically modified agriculture are suckers at all. I think they are people who are wise enough to understand the limits of scientific knowledge.

Now, because we can all see the knee-jerk response such a statement invites, let me say: I will cede to no person – no layperson, anyway – in my love of, appreciation for, and wonder at the scientific endeavor. Nothing else in human history even comes close to the glory of that cooperative, intergenerational, millennia-long project. We should engrave a summary onto brass tablets and blast them into space under the headline “LOOK: WE FIGURED SOME OF IT OUT.”

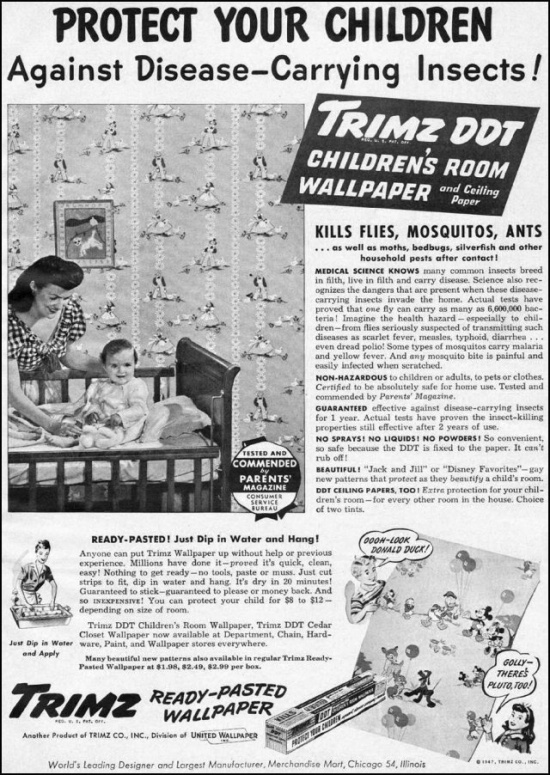

Poster advertising the benefits of Disney-adorned, DDT-laced wallpaper for use in children’s bedrooms. “Certified to be absolutely safe for home use!”

But the first requirement of scientific inquiry is skepticism, and that includes a healthy appreciation of what science can tell us and what it cannot. To put it crudely: Science can tell us what will happen if you pour Beaker X into Flask Y. It can even tell us, with a great degree of certainty and despite the lack of perfect experimental conditions, many more complicated things – for example, the reason that salmon runs on the Klamath have declined over the last few decades.

What science cannot do is answer the question: “Hey, if we decide to reach down and fiddle with the wiring of life itself and then let industry spread our cool new creations all over the globe … nothing really bad is going to happen a hundred years from now because of that, right?”

Science cannot answer that question because the question is ill-defined, and because science is not soothsaying. Go take it to any freshman biology student and ask her to research the answer. The student will laugh in your face, and her professor will call campus security to have you ejected from the premises – quite rightly, too. The glory of science is, in large part, its refusal to offer answers to unanswerable questions. If Lori Dengler were running around saying that the Cascadia Subduction Zone is going to slip next Friday at noon and we are all going to die, we would call her a quack. Instead she says that it is going to slip sometime – probably sooner rather than later, geologically speaking – and its effects will be dramatic. Given enough time and patience she can show you why. She is a scientist.

Nevertheless, and regardless of the proper silence on the subject from the scientific community, that basic question – what does the world look like after 100 years of rampant genetic engineering? – is an important one for a democratic society to keep in mind. We are right to be wary of the fact that it has no answer. Given our clumsy, relatively recent Promethean ability to push the systems that support life on our planet to the brink, we would be derelict not to regard our own technological innovations with suspicion.

The engineers – science in service of power – are always several steps ahead of science disinterested. We know we can do something long before we know what the consequences will be. Forty years passed between the drilling of the world’s first commercial oil well and Svante Arrhenius’ first, tentative notions that the mass combustion of fossil fuels may affect the planet’s climate. Many more decades passed before anyone thought to get serious about the problem. At the dawn of the nuclear age, the whole thing repeated itself – people rejoiced at the prospect of unlimited cheap power from the atom. Twenty-five years passed between the spinning-up of the first commercial nuclear power plant and Three Mile Island.

This year marks only the 20th anniversary of the Flavr-Savr tomato, the world’s first commercial genetically modified crop. Today, 433 million acres of genetically modified corn, soybean, sugar beets, cotton, alfalfa and other GMO crops are in production worldwide. The vast majority of all corn, soybeans, canola and sugar beets grown in the United States are now genetically modified. Genetically modified animals have only recently been licensed. This is a stunningly rapid rate of adoption.

The scientific community can debate and test the potential problems it can identify at this early, Arrhenius-like stage of the game – pollen drift, the effect of this crop or that on wildlife or human health, the environmental effect of the increased use of pesticides many of these crops are designed specifically to accommodate – but it cannot address questions that no one yet has the vocabulary to ask.

And the agricultural shift we are undergoing right now is far more profound that the shift from coal to oil, from barbiturates to Thalidomide, from the blunderbuss to the atom bomb, or even from oil to nuclear energy. We are tinkering with two fundamental systems – the internal processes of life, and the ecological systems that allow our Earth to support it – that we, as a rational species, only barely have a grasp on. Modern genetics and ecology are in their infancy.

No one denies the immense, immediate tangible good offered by something like golden rice. But neither should anyone presume to deny that human beings have, by now, a long and venerable history of blunders and whoopsies and “didn’t see that one coming!”s both small and enormous.

It will not hurt us to be among the cautious ones. We can do well by doing good. Let’s slow it down, Humboldt.

YOU’VE HEARD HANK, NOW HEAR BURNS.

CLICK TO MANAGE