Dr. Michael Fratkin wants to change the way people live when they’re getting ready to die. He wants to change how families experience the dying process of a loved one. And he believes that these changes, if they catch on, could revolutionize our broken health care system and transform the way our culture deals with death.

Dr. Michael Fratkin wants to change the way people live when they’re getting ready to die. He wants to change how families experience the dying process of a loved one. And he believes that these changes, if they catch on, could revolutionize our broken health care system and transform the way our culture deals with death.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

As the director and founder of St. Joseph Hospital’s Palliative Care program, Fratkin has cared for many, many people as they approach death. Somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 people have died under his care, he estimates.

As modern medicine continues to extend life expectancy — especially drawing out people’s last days, weeks and months — Fratkin has seen how the health care system in the United States encourages, even incentivizes, quantity of life over quality.

“Back in the day you got sick and you died; that was the trajectory of things,” Fratkin said. “We didn’t have two, three, five-year periods where we know we have the disease that will kill us.”

Despite this awareness, families are often reluctant to talk frankly about worst-case scenarios, to ask loved ones exactly how, where and under what conditions they hope to spend their final hours. The result is that people often don’t die the way they would choose.

Most people in the United States would prefer to die at home rather than in an institutional setting, surveys have shown. And yet only about one in four people over the age of 65 gets to do so. As Forbes recently reported, “People are also being hospitalized more frequently in the last three months of their lives, are more likely to spend time in intensive care units, and are often receiving hospice care for just a few days before they die.”

Many families simply can’t deal openly with the prospect of death. Fratkin’s was one of them, and he still remembers the revelatory moment at age 7 when he saw his grandfather’s body lying inside a casket at his funeral. Fratkin had loved and admired his grandpa. “He was about four feet, 10 inches tall, but he was a giant to me,” Fratkin recalled. When his grandma and grandpa visited from New York City they’d bring smoked fish, bagels and chocolate cake.

“He was one of the only grown-ups I knew who knew how to show up for kids, respect them for what they were,” Fratkin said. “He was so good and kind. And then he stopped coming.”

A year later Fratkin’s family told him that his grandpa had died. He’d been sick, but the family didn’t discuss it. The family traveled to New York City for the funeral, and Fratkin remembers feeling betrayed.

“I was this kid,” he said, “and everybody was walking around with platitudes and ‘now-now’s, patting me on the head. I was angry.” Eventually it came time to view the body. “I walked up to casket, looked inside, and I realized, ‘That’s not him. We are not our bodies.’ And that just sat with me.”

That knowledge informed Fratkin’s career, which led him from volunteering with a Hospice in Florida during the AIDS epidemic to becoming a doctor and working at Tampa General Hospital.

While there he recognized that the health care system was missing the forest for the trees. “I realized that people weren’t being seen for the people they are but the problems they had,” he said. Patients, meanwhile, experience their medical care “from middle of who they are and where they live,” Fratkin continued. The various treatments at our disposal develop a momentum all their own, often taking patients down paths they wouldn’t necessarily choose if given the option.

Fratkin says this system is both insensitive and outdated, especially given the attitudes of Baby Boomers, Gen-Xers and even millennials, all of whom have been seeking more empowerment over their own health care compared to previous generations. “They don’t necessarily want more, more, more,” Fratkin said is a recent interview. “They want the information to make their own calls.”

Data reflects these shifting attitudes. The percentage of Medicare beneficiaries dying in acute care hospitals has been falling over the past 15 years while the percentage of people 65 and older who died at home climbed from 15 percent in 1989 to 24 percent in 2007 [source]. Palliative care is becoming more and more popular.

Fratkin believes it’s possible to create a new and better system for delivering health care to the terminally ill, a system grounded in patients’ values, desires and holistic experiences rather than simply their symptoms. To this end, he recently embarked on an endeavor he’s dubbed Resolution Care, a multi-faceted project that aims not only to improve in-home palliative care for the people of Humboldt County but also to duplicate this type of care elsewhere in the state and beyond, especially in rural areas like ours. And the kicker? He’s hoping to finance this program’s start-up costs largely through online crowdfunding.

“I am crowdfunding a complete end-of-life care team,” Fratkin said with a hint of impish delight. He plans to assemble physicians, nurses, support staff, even a chaplain, all focused on providing what Fratkin calls “soulful, compassionate care” for people who are seriously ill but not yet ready for Hospice.

On Nov. 1 (Dia de los Muertos, appropriately enough), Fratkin will launch a Resolution Care project page on the fundraising website Indiegogo, an approach that he admits is unorthodox. “Nobody’s been crazy enough to crowdfund a team of professionals,” he said.

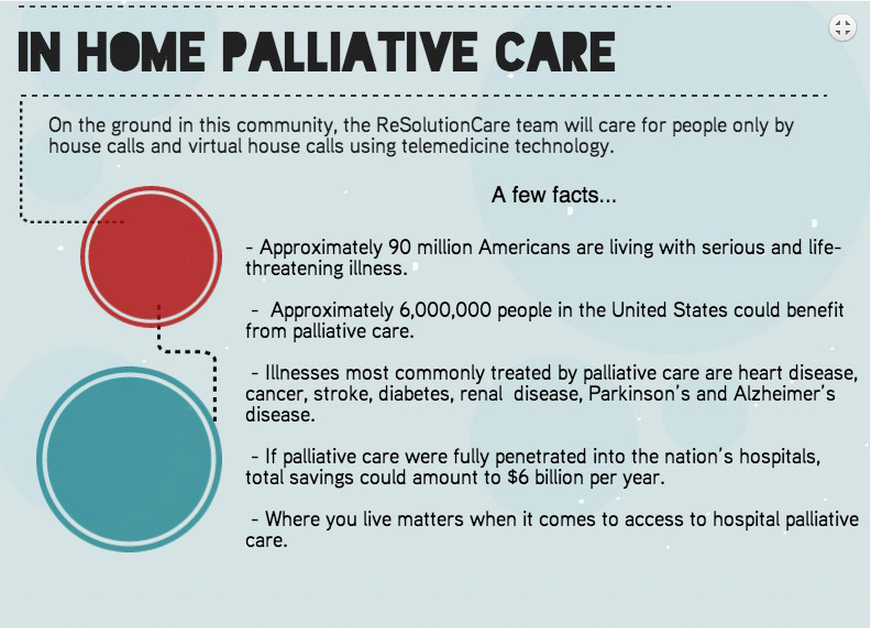

Infographic from the Resolution Care website.

Infographic from the Resolution Care website.

The team of professionals Fratkin has assembled will do three things, he explained. First, they will provide outpatient palliative care to people in their own homes, either via house calls or through virtual house calls using telemedicine technology.

Secondly, Resolution Care will provide telemedicine consultations to patients anywhere in California, particularly in rural areas where palliative care is lacking. Fratkin said these consultations can support the care that people are getting in their communities.

The third mission of Resolution Care will be to reproduce this palliative care model elsewhere in the state. This facet of the project, which will take place under a nonprofit operating in tandem with the corporation required for clinical services, is what Fratkin is most excited about.

The inspiration came a revolutionary program out of the University of New Mexico called Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes). A few months back Fratkin read a profile of the project in the New York Times and had what he called an “ah ha” moment.

Project ECHO was started nearly a decade ago by a hepatologist at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine named Dr. Sanjeev Arora. He had noticed problems with the treatment of New Mexico residents who had the contagious liver disease hepatitis C. Specialists were concentrated in urban areas while afflicted patients were spread across the state’s vast rural regions. Consequently, less than 5 percent of New Mexico’s estimated 34,000 chronic hepatitis C patients had been treated.

Determined to improve this situation, Arora traveled around the state meeting with care providers in rural areas, explaining that better care was possible with help from experts on the disease. As the New York Times reported,

He made an offer. If [these rural providers] volunteered to spend two hours a week with him, he and other specialists would work with them in close collaboration until they could manage their own cases.

Back in Albuquerque Arora assembled a team of specialists, and through videoconferencing they began conducting weekly case-based training sessions for caregivers across the state. Thanks to grant funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Project Echo quickly spread across the state, and it produced impressive results. Again, from the New York Times:

In 2011, the New England Journal of Medicine published a study that compared the cure rates of patients treated at the University of New Mexico’s HCV [hepatitis C virus] clinic with those treated by primary care clinicians in 21 remote ECHO sites, including federal and state run health centers and five prisons. The study reported that the primary care clinicians achieved slightly better cure rates and their patients had fewer serious adverse events. The research suggested that, when treated in local settings, patients adhered better to treatments; and primary care doctors more familiar with patients’ medical histories and personal situations could better coordinate care and anticipate problems.

This resonated with Fratkin, who had long seen the benefits — both mental and physical — of in-home palliative care. Not only are patients and family members more at peace when they’ve had conversations with palliative care specialists, but the patients also wind up spending less time in the hospital and, perhaps surprisingly, living longer.

A 2010 study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that “integrating palliative care early in the treatment of patients with advanced lung cancer not only improved their mood and quality of life, it also extended their lives.”

In recent years, Project ECHO has grown dramatically by expanding its model of hubs and spokes — that is, centralized “hubs” of expertise that disseminate knowledge through telecommunication “spokes” to a network of geographically diffuse caregivers. The project now involves more than 30 hubs dealing with 26 specialties including rheumatology, H.I.V., dementia, breast cancer and more.

Here’s Arora explaining the project’s success:

Resolution Care, Fratkin’s palliative care endeavor, has partnered with Project ECHO in the hopes of duplicating its model and its successes. Fratkin and his project partner, Acute Care Nurse Practitioner Karen Ayres, recently returned from Albuquerque and have been planning the way forward.

“We will create learning units, or spoke sites, in primary care practices, dialysis centers, oncology practices and more,” Fratkin explained. “Special thought will be needed for each category, but the opportunities and options are vast.”

Resolution Care has partnered with a variety of organizations including St. Joseph Hospital, Heart of the Redwoods Community Hospice and Redwood Urgent Care. Fratkin said that a private supporter has donated $10,000, and he’s working with other donors to try to raise $100,000 in matching funds for the crowdfunding endeavor.

Organizers are still working out the rewards that will be offered to donors, but a few have been lined up. For example, a $100 donation will get you an autographed copy of Dr. Ira Byock’s book “The Best Care Possible”; renowned local sculptor Peggy Loudon will handcraft “prayer bowls” for people who donate $1,000; and $2,500 donors will be able to work with San Francisco artist Mary Mar Keenan to create a unique ceramic urn.

If the project had to rely on the traditional fee-for-service model, Fratkin said, it would be sunk immediately. And going forward it will likely depend on grant funding, federal and state money. As the New York Times said of Project ECHO, long-term, nationwide success for this model will depend on governments and insurance companies developing a standardized reimbursement approach.

Fratkin thinks this model of shared expertise would ultimately prove a better value for society. Resolution Care’s approach, he said, can transform not just palliative care but potentially the entire health care system. “My sense,” he said, “is that if we can sort out a proper and soulful way to care for people as they face their death, we can kind of work backwards and transform the health care system.”

For more information visit the Resolution Care website.

CLICK TO MANAGE