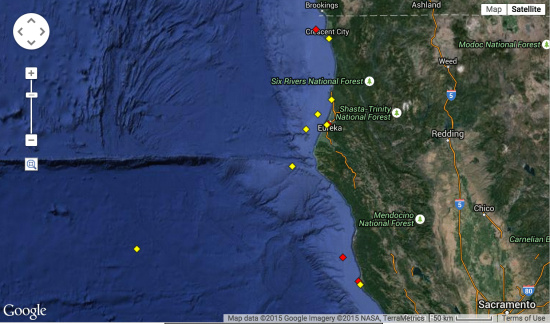

From the National Data Buoy Center via NOAA.

It’s the same thing every morning: You turn on the computer, start your coffee and, while it’s brewing, take a look at the buoys. The 22 is your go-to for the larger picture of what’s happening right now, wind and swell-wise. The good ol’244 tells you the immediate offshore action. Some folks even take a look at the 213! If you plan on interacting with the ocean on any given day, the combined info these buoys provide determines not only where you go, but if you go at all.

But depending on the outcome of Wednesday’s California Dept. of Boating and Waterways meeting, those who depend on the ocean for their livelihood and/or recreational needs may lose both the North Spit (244) and Cape Mendocino (213) buoys – the very ones featured on your LoCO Ocean page! – those two are “Scripps” Waverider buoys, whereas the Eel River buoy is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) network.

This is where it gets really wonky. Hang with us as the acronyms come at you. See, the Scripps buoys are part of the Coastal Data Information Program (CDIP), which is jointly funded by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Division of Boating and Waterways (DBW), the U.S. Navy along with other entities, and staffed through contracts with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

So why is the state considering taking our two Scripps buoys away?

According to California Parks and Recreation Deputy Director Colonel Christopher C. Conlin, USMC (Ret), the matter has come under consideration due to advances in wave science, “especially the reliability of wave models for the California coast and the increased reliability of the permanent NOAA National Data Buoy Center (NDBC) wave buoys.” Therefore, Conlin continued, a reduction of CDIP buoys is being considered to avoid redundancies and offset increasing costs.

“We have not made any firm decisions,” he said, “but we will be determining buoy priorities based on the criticality of their specific data collection and resources available.”

Despite the perceived reliability of the NOAA buoys, North Coast buoy report users know that the 22 goes offline not infrequently – the buoy went adrift in November, 2014 and a replacement not deployed until four months later.

And when things do go awry, explained Troy Nicolini, Meteorologist in Charge at the National Weather Service’s Eureka office, getting them fixed is “a real challenge.” The NOAA buoys are large, Nicolini said. “They take a big ship from 1,000 miles away to service them.” That means the 22 can be offline for months at a time as the ship makes its way up and down the coast.

In contrast, the Scripps buoys are “little one meters” that can be serviced by Humboldt State University’s Coral Sea.

At the moment, the U.S. Army Core of Engineers has offered to provide temporary funding for the 244, but if the state does not hear sufficient outcry about the funding cuts, then it, the Cape Mendocino buoy and almost all the Scripps buoys on the coast are likely to go away. DBW staff is currently soliciting input from boating interests and the Boating and Waterways Commission will consider the options at its public meeting, Wednesday, Aug. 26 at 9 a.m. in the Humboldt Bay Aquatic Center.

CLICK TO MANAGE