Two weeks from now, on Aug. 4 and 5, the California Fish and Game Commission will hold its regular meeting here in Humboldt County, at Fortuna’s River Lodge Conference Center, and during its Wednesday session the commission is scheduled to decide whether or not to ban bobcat trapping statewide.

It’s a controversial issue, with some groups lining up exactly as you’d expect — environmental nonprofits supporting a ban, trappers and hunters opposing — while others say more information is needed before a decision is made.

Here in Humboldt, the Environmental Protection Information Center (EPIC) has joined the campaign supporting a ban. In an action alert posted on its website, EPIC points out that commercial bobcat trapping in the state is largely driven by the foreign market value for the cats’ pelts, particularly in China and Russia.

The Humboldt County Board of Supervisors, meanwhile, opposes the ban, saying the Fish and Game Commission lacks the authority to take such a sweeping action and should instead take the alternative approach: establishing no-trapping buffer zones around state and national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, where trapping is already prohibited. (Hunting bobcats would still be allowed, as would trapping problem bobcats, such as those threatening livestock.)

These two options — a statewide ban or a zone-based approach — represent the two alternative paths that the Fish and Game Commission could take as a means of implementing a state law that passed two years ago: Assembly Bill 1213, aka the Bobcat Protection Act of 2013. That law focused on the area surrounding Joshua Tree National Park, where bobcat trapping had become a hot-button issue after trappers illegally captured and killed a number of bobcats on private property. But the law also instructed the commission to consider extending the ban to lands “within, and adjacent to, preserves, state conservancies, and any other public or private conservation areas identified to the commission by the public as warranting protection … .”

Those are pretty vague criteria, and late last year the commission started discussing the possibility of making those protected areas really big — as in, big enough to encompass the entire state.

Some background

Bobcat trapping used to be a relatively big business in California. Until the 1970s there were no protections for bobcats and no restrictions on the “take” or “harvest” of the animal. But in 1971, with domestic and international demand for bobcat pelts rising, the state legislature gave the species non-game status. Since then California has issued trapping licenses and kept track of how many are killed each year during the official trapping season, which runs from Nov. 24 through Jan. 31.

During the 1977-78 season more than 20,000 bobcats were killed in California, but shortly thereafter the bottom began to drop out of the market. Below is a chart showing the total number of bobcats killed by people (in an official capacity, at least) from the 1976-77 season through the 2013-14 season (the most recent stats available).

Data source: California Department of Fish and Wildlife

You can hover over each bar in the graph to get the information for each season. Bobcat pelts, like pretty much every other market, are subject to the laws of supply and demand. The average price for a pelt dropped from a high of $167.33 in 1986-87 to just $17.91 three years later, and the take numbers have been comparatively low ever since.

But demand began to rise again in the early 2000s, driven by people in Russia and China (and, to a lesser extent, Eastern Europe) who want the thick, soft pelts for fur coats and showpieces. While the official stats from Fish and Wildlife put the average price of pelts at $390 in the 2013-14 season, wildlife advocates say they’ve gone as high as $2,100 apiece. The cost of an annual trapping license, meanwhile, is just $115.

To many, this practice seems fundamentally barbaric and morally wrong. (The San Francisco Chronicle, for example, quoted a fourth-grader who said, “It is disgusting that people are killing the beautiful bobcats.”)

Natalynne DeLapp, executive director of EPIC, agreed that it’s a moral issue, but said it’s also an economic and scientific one. The bobcat is an important and highly adaptable mid-sized predator, DeLapp said. She added that while both options before the commission would help protect the species, a trapping ban makes more financial sense.

EPIC has joined forces on this issue with the Center for Biological Diversity, which estimates that the zonal approach to bobcat management would cost nearly $600,000 per year, far more than the state brings in from trapping licenses and shipping tags for sales and exports.

“When we write our comments [to the commission] we do have to look at the issue from an economic standpoint to justify our larger reasoning, which is the intrinsic value” of bobcats, DeLapp said.

How many bobcats?

Both EPIC and the Center for Biological Diversity call attention to the fact that Fish and Wildlife’s estimate of the total statewide bobcat population — 72,000 — is more than 35 years old, and a somewhat dubious figure to begin with.

When Governor Edmund G. “Jerry” Brown signed AB 1213 into law in October 2013, he issued a signing statement [pdf here] calling for a new bobcat population survey, though no such effort has been undertaken.

Dr. Greta Wengert is the assistant director of the nonprofit Integral Ecology Research Center, based in Blue Lake, and she has studied bobcats fairly extensively in northwestern California and the southern end of the Sierra Nevada range. But she also doesn’t know how many bobcats there are in California.

“I don’t think anyone has a good estimate at all,” she said.

A more important consideration is the bobcat population in each specific ecosystem, Wengert said. She described bobcats as “a cosmopolitan species,” meaning they live not only in forest ecosystems, where they interact with fishers, martens and mountain lions, but also on the outskirts of urban areas in Southern California, where they’re threatened by development and habitat encroachment.

Circumstantial evidence suggests that bobcats are not a threatened species from a statewide perspective, according to Wengert. For one thing, the harvest numbers are low compared to both the past and to other states. “From a population perspective, the amount [of bobcats] harvested each year does not seem like it will affect the overall bobcat population,” she said.

But again she mentioned that specific bobcat communities could indeed be threatened.

“I feel like there’s a lot of information missing on which to base decisions, and it [regulation] may have to become a local question,” Wengert said.

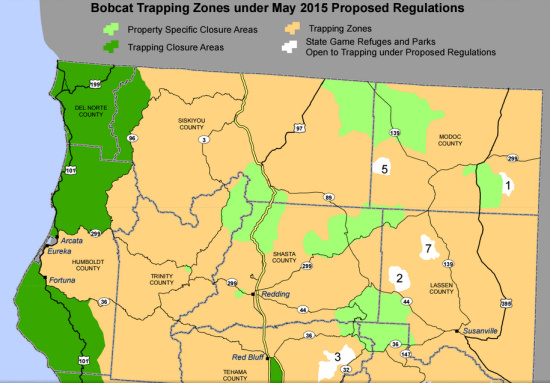

The zonal approach to bobcat management aims to take those sensitive bobcat populations into consideration. Below is a map showing the proposed zones in our part of the state (Click here big pdf version of the statewide map).:

Courtesy California Fish and Game Commission

Bobcat trapping is not hugely popular in Humboldt County. Here, have a look:

Data source: California Department of Fish and Wildlife

More than 500 bobcats were killed here during the boom season of 1987-88, but there hasn’t been more than 10 harvested in any year since the 2000-01 season. (The blank spaces reflect gaps in the data, not years with no harvest.) The low prevalence of trapping here might be due to the fact that desert-dwelling bobcats tend to have thicker, softer and more spotted pelts than those of cats living this far north, Wengert said.

Regarding the original law, Wengert said Joshua Tree National Park is known for having “really healthy bobcat populations.” That being the case, trapping done outside the park is not likely to threaten the overall population.

“It’s almost like they’re surplus animals,” she said, before quickly adding, “That’s only from biological perspective. Ethics are a different issue; I’m not gonna go there.”

The legislative process

The Humboldt County Board of Supervisors doesn’t go there either, though they do oppose the ban. Back in January, the board unanimously voted to send a letter [pdf here] opposing that option to the heads of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the California Fish and Game Commission. As Board Chair Estelle Fennell recently explained to the Outpost, the supervisors’ opposition to a ban was based not so much on a philosophical or ethical stand as on procedural concerns. (Siskiyou County supervisors sent a letter articulating the same objections in March.)

“It was actually based on a request from [Humboldt County’s] own Fish and Game Advisory Commission,” Fennel said. “Their concern, and subsequently the board’s, was about circumventing the legislative process.” As the board sees it, an outright state ban on bobcat trapping was duly considered and rejected by the state legislature back in 2013, during debate on the law itself. Implementing the ban now would be overstepping the commission’s authority, the board letter argues.

Furthermore, Fennell noted, the board thinks the Department of Fish and Wildlife should undertake the population survey requested by Governor Brown.

The Department of Fish and Wildlife, for its part, has endorsed the zonal approach, basing its argument on numbers and science. (The agency suggests charging a new annual bobcat trapping validation fee of $1,137 to offset the increased costs of management.) But Sonke Mastrup, executive director of the Fish and Game Commission, said morality issues are not beyond the scope of the five-member commission’s criteria for making such decisions.

“As I like to tell folks, the commission’s job is to balance what the science calls for and what the public will tolerate,” Mastrup said. “Science is certainly a foundation, but it’s not the only thing that goes into to making a decision.”

The commission will also consider public testimony and other information provided during the course of deliberations. But Mastrup said that, so far, advocates for a total ban have focused on the moral aspect.

“Based on the testimony I’ve been hearing, it’s more about the morality or ethics of whether we should be allowing people to commercially exploit bobcat furs,” Mastrup said. “Mostly [the testimony] boils down to: We just don’t like it.”

(And if you’re at all prone to such feelings, browsing websites like CagingBobcats.com or the Facebook photos of Camtrip Cages will likely stir your sympathies.)

Mastrup said it’s also possible that no decision will be reached at the Fortuna meeting. The commission could opt to implement one of the two options, it could postpone the decision or it could say it doesn’t like either option and come up with another approach altogether.

EPIC will be hosting a “teach-in” the Monday before the hearing from 6-8 p.m. at the Arcata Community Center’s Arts and Crafts Room. The event will also address a couple other items on the commission’s agenda, including a request to list the Pacific Fisher under the California Endangered Species Act as well as EPIC’s own petition to add the Humboldt marten to that list.

As for the bobcats, there’s at least one point on which seemingly everyone agrees: Better data is sorely needed.

“The bottom line for me,” Wengert said, “is that the state really needs to invest in really good bobcat population numbers.”

Thus far there have been no specific proposals to do so.

If you’d care to attend the meeting (or live-stream it through cal-span.org), you can download the agenda ahead of time here.

CLICK TO MANAGE