Eureka was awash in the scales, skin and flesh of a fresh-caught Chinook, whose precious pink meat was sloppily shorn into lopsided bricks in the stainless steel trough of the fish market sink.

Amidst the meat and viscera, thin tendrils of red circled the gurgling drain: Blood from a deep slice across the fingertips of my left hand. It came in spurts, like an overdone special effect from B-movie Hollywood, and it hurt.

The crowded dining room behind me, beyond the waist-high glass case that displayed the day’s selection of local ocean bounty, remained oblivious to the carnage, even as several of my white-shirted coworkers dashed back and forth in a low-grade panic, determining how exactly they were going to evacuate their apprentice fishmonger with minimum fuss.

This was old Eureka on parade.

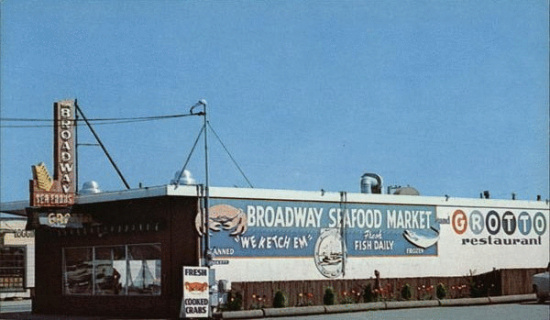

Black kitchen chairs set round plainly outfitted dining tables, maritime regalia tacked crookedly to greasy walls, a faded linoleum floor scuffed over years by the sneakers and boots of restaurant staff, and a garishly lit aquarium that whispered a tuneless drone to the recently arrived customers as they filed in through the glass doors and stepped into line, the Eureka Seafood Grotto wasn’t high dining, and rated no stars from pretentious, metropolitan food critics.

It was a dive, but a comfortable one. Around the tables, most anxiously awaiting their delicious dollop of homebrewed clam chowder, were the salty remnants of Eureka’s past and fading present: Old fishermen and their wives, blue hairs happy with the food they know, suits just in from their monthly Chamber of Commerce meetings, and the occasional — though increasingly rare — fisher himself, most often in jeans and flannel, bearded, tan like fawn leather, proud.

They’d been coming here for decades. Adults who were first dragged in 30 years prior were now dragging and shushing their own kids through the door, prying them away from the sweat-smeared glass of the fish tanks to settle them into high chairs and booster seat that had seen better days.

The Grotto was my introduction to an early yet definitive aspect of this Victorian Seaport, hearkening back to the extractive roots of our now sputtering North Coast economy.

For more than a century, residents here often made their living — and a good one — by felling ancient trees or hauling lines and nets from the deep and rich waters of the Pacific Ocean. But those old cash cows were ailing, their udders recently corked by environmental degradation, increased regulation, and diminishing profit.

It was 1994.

I’d found a job at the greasy Sixth Street restaurant and fish market through my sister-in-law — her mother had for years been the manager of the restaurant’s quaint fish counter, a narrow case of glass and stainless steel that abutted the back end of the dining room. Under the case lights: Petrale sole, rock cod, sand dabs, swordfish, mahi tuna, albacore, ling cod, halibut, scallops, bay shrimp, squid, prawns, dungeness crab, the occasional octopus and — by strangely popular demand — the foul lutefisk of Scandinavian lore.

The Grotto’s best days were long gone at this point. Already, Eureka Fisheries — soon to go under — was struggling with the same disease that would ultimately bring the company down. And the Grotto — within the company always a peculiar mix of flagship and bed-headed step-child — was often the first to feel the pain: Low wages, minimal investment, duct tape and bailing wire.

The customers were aging, the industry changing, and the old dive’s long career was mired in permanent ebb tide. Still, it had its charm. Often, while pacing the slats behind the fish counter, watching the clock and pushing my towel around in tight circles, I’d squint my eyes and see the place for what it had been, for what Eureka had been — salt-burnt and wise, tough as shit, fierce in the face of a hard storm, and on the lookout for a good time.

Nineteen, and a college dropout, at times I worked hard there. On Christmas Eve, for instance, under constant assault from the long lines of holiday-weary patrons, I spent 14 hours bent over the same sink backing more than 2,000 pounds of crab until my wrinkled hands cramped and my thumbs throbbed from handling one sharp-edged orange shell after another.

I also learned that all of this was a sadly fading future.

Whereas I sensed the depredation and doom looming over both the restaurant and the company, not to mention the industry itself, my predecessors — those of my parents’ and grandparents’ generations — succumbed to the lull of quick money that fishing, as well as timber, had provided.

Instead, I knew I had to get out.

After an initial semester of failure at College of the Redwoods, followed by another semester off, I enrolled again that next year after working a full season at the Grotto. Whether it was learning the value of hard work, or simply refusing to leash myself to a career in food service and fish scales, crab butter and reeking meat, something in me had shifted. School, suddenly, seemed the quickest route to write for a living. At a desk, where the wounds had all healed.

Unlike my bloody fingers. Try as I might that day with one towel after another, cotton gauze and a tubful of Neosporin, no amount of pressure or maneuvering seemed enough to staunch the flow of blood from my lacerated middle and ring fingers. The fillet knife I’d stowed for personal use was damn sharp, and did its work just as well on me as on its intended salmonid targets. We weren’t that different after all.

Sensing my concern, Jim, the head cook, took charge. A lanky Texan with feathered hair and cowboy boots, he was a library of anecdotes and exaggerations. He’d been on the job for three months and the luster his bravado had initially afforded him was rapidly fading under the stain of his foul temper, demonstrated ineptitude, and culinary catastrophes.

After spotting my wound, the self-described combat veteran dashed into the busy waitress station up front and grabbed a handful of coffee straight out of the can. Back behind the fish counter in seconds, even as his kitchen overflowed with tickets and normally peaceful patrons grew restive with hunger, he stooped down to look me straight in the eye.

Man to man. Cook to fishmonger.

“Here’s a little trick I learned in battle,” he said, then flung his handful of coffee grounds into the yawning cuts on my hand. To stop the bleeding, he said.

As a waitress led me out the door for the ride to the Emergency Room, Jim played the hero and looked me up and down as if verifying the results of his intervention. Flustered, I thanked him for his help, and he patted me on the back.

“Nothing you wouldn’t have done for me,” he said.

Hours later, as the doctor finally finished removing every last ground from my wounds with tweezers and a magnifying glass, he shook his head.

“Don’t ever do that again,” he said. “It’s not like you were bleeding to death.”

At the Seafood Grotto, the lessons were just piling up. And Jim, of course, was right as always: There’s nothing I’d enjoy more, even now, than rubbing some grit into his open wounds.

###

James Faulk is a writer living in Eureka. He can be reached at faulk.james@yahoo.com.

CLICK TO MANAGE