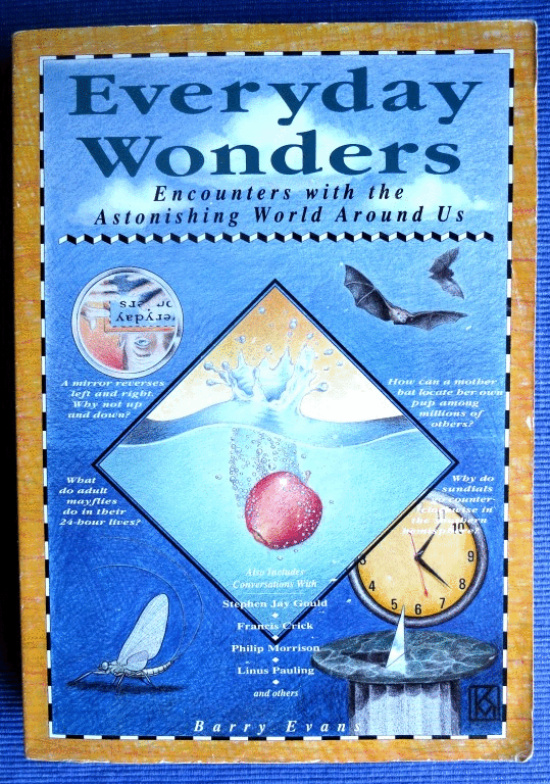

The hardest thing I’ve ever done was the 18 months I spent writing my second “real” book (i.e. published by a real publisher, in this case a subsidiary of McGraw-Hill), Everyday Wonders: Encounters with the Astonishing World Around Us. Featuring, as the cover breathlessly promised, interviews with Stephen Jay Gould, Linus Pauling, Francis Crick and others (!). It was published in 1992, sold some 12,000 copies (not too shabby for a popular science book from a no-name author) and I received $12,500 from the publisher. For which I was thrilled. Still am.

I chose to read part of the intro last Wednesday evening at Old Town Coffee and Chocolate’s open mic night. People seemed to like it, so I’m reproducing it here, unedited. (Or as the ghost in Hamlet says, “No reckoning made, but sent to my account/With all my imperfections on my head.”)

###

In the fall of 1978 I had just returned to North America after a year-long round-the-world odyssey. It had been a time full of rich experiences and new friendships, but light on personal insight, which is really what I’d been seeking on my wanderings. To remedy this minor omission, I enrolled in a nine-day Buddhist retreat held on the beautiful, ocean-bounded grounds of a Catholic seminary on Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

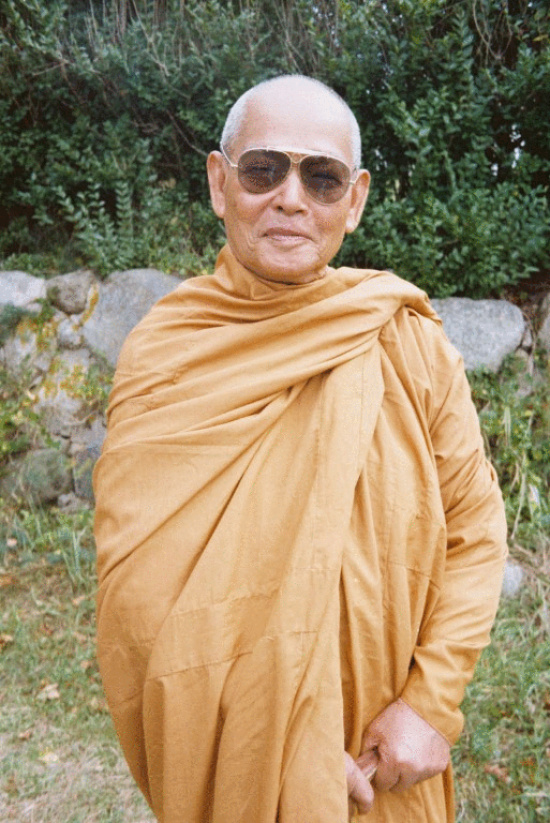

The retreat was intense, involving about ten hours of meditation each day. It was also silent. We dressed silently, ate silently, showered silently and walked silently, so as not to disturb the inner rhythm of concentration. The only exception to the rule of silence was a half-hour period after lunch each day, when we could approach our 81-year old master, a Cambodian monk living in the U.S., and ask for help with our contemplation. I decided at the outset that, as a matter of personal pride, I wouldn’t take advantage of this respite. By the third day, I’d repented.

“Bhante,” I said, “I’m having so much trouble with my meditation. My mind is constantly distracted and I never seem to stay centered for more than a few seconds at a time. What’s really frustrating is that I’ve been meditating on and off for about ten years, and this is even worse than all those other times in the past when I couldn’t maintain my focus. Can you help me?”

He looked at me with his ageless, jolly, baby-blue eyes. “That was then. This is now,” he said. That was it. He didn’t add or expound on these words. I finally nodded, thanked him, and he rose, bowed, and left me sitting there.

“That was then. This is now.” Those six words have stayed with me for fourteen years. When I find myself worrying about the future or feeling remorse about the past, the words come back. They foreshadow one of my purposes in writing this book: to celebrate the present.

His words are here now, an immediate mental response to any regrets I have about the past. All my “could’a, should’a, would’a’s” are transmuted into, “That was then. This is now.”

Bhante’s words echoed, with remarkable brevity, the delicious pragmatism of Edward Fitzgerald’s Omar Khayyam:

The moving finger writes, and having writ

Moves on; nor all your piety nor wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a line

Nor all thy tears wash out a word of it.

If the past is immutably frozen, the future is a fluid vision that may or may not come to be. Even the next few hours are uncertain, no matter how clear our plans. Days, weeks and months ahead blur into uncertainties. I suppose Bhante would say about the future: “That will be. This is now.”

Which brings us, by a not-too-subtle process of elimination, to the present. This book is about the present, because it’s about awareness: noticing, stopping, looking, heeding, remarking, observing, beholding, discerning, perceiving, asking, examining, probing, considering, pondering, weighing, appraising, studying…right now.

It’s about wonder.

###

Everyday Wonders was in print until recently. It’s still available, although not for its original $14.95 retail price (which today would be $24.95). Nothing like the humbling realization that one’s baby, a year-and-a-half in gestation, can now be picked up as an ex-library copy for just a penny.

Plus $3.99 shipping.

###

Barry Evans gave the best years of his life to civil engineering, and what thanks did he get? In his dotage, he travels, kayaks, meditates and writes for the Journal and the Humboldt Historian. He sucks at 8 Ball. Buy his Field Notes anthologies at any local bookstore. Please.

CLICK TO MANAGE