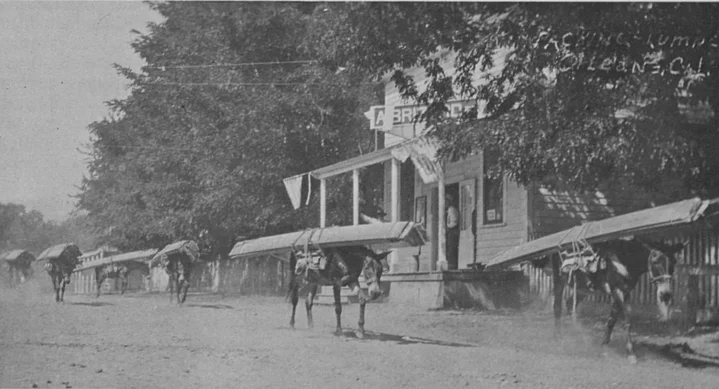

After a long, hard trip from Blue Lake and Korbel, this pack train arrive« at Orleans with its cargo. Strung-out along the road, they walk independently and at a steady pace. This photo and the one below were taken in 1920. Photos via Humboldt Historian. Click to enlarge.

When the miners had depleted the lowlands, the easy-to-get-to gold claims, they pushed on through the forests, into deep canyons. They climbed the rocky mountains to find streams running white with rapids — always in the hope that here may be a new bonanza. As the miners moved, they left behind them the easier, faster methods of transportation. No longer could they go by locomotives, stagecoaches, wagons. At times it was almost impossible for four-footed animals. It was necessary for supplies and machinery to be carried into the mining country, where settlements cropped up almost overnight with population numbers running into the hundreds. Like magic, rumors of gold drew masses of humanity.

The pack train became an indispensable necessity, linking the mines with civilization and the source of supply. In some of the more isolated localities, the arrival of a pack train was an event of importance. The mule pack train can be given a major portion of credit for the early-day development of Humboldt’s interior, the country of northern and northeastern Humboldt County.

A. Brizard’s famous pack train shared in this growth. Besides serving the branch stores in the mining country, the pack trains carried freight — pipe, machinery, supplies — for the mines. It was reported, as the packing season came to an end, Brizard pack trains had carried a half-million pounds. Brizard was not alone in packing, for there were numerous operators serving the countryside.

This picture shows how needed lumber was brought into communities on the back of mules. They pass the A. Brizard store at Orleans.

According to Hutching’s California Magazine, December 1856, “There are generally forty to fifty mules in a train, mostly Mexican, each of which will carry from three hundred to three hundred and fifty pounds, and with which they will travel from twenty-five to thirty-five miles per day, without becoming weary.”

In Humboldt, the mileage accomplished was shorter, because of the mountainous country. The mule trains passed over some of California’s ruggedest terrain to reach their destinations.

Hutching’s said:

If there is plenty of grass they seldom get anything else to eat. When fed on barley, which is generally about three months of the year, November, December and January, it is only given once a day, and in proportions from seven to eight pounds per mule. They seldom drink more than once a day, in the warmest weather. The average life of a mule is about sixteen years.

The Mexican mules are tougher and stronger than American mules; for, while the latter seldom can carry more than from two hundred to two hundred and fifty pounds, the former can carry three hundred and fifty pounds with greater ease.

It was not possible to carry food in the freight train, enroute. At night at the end of the run, the mules were turned loose to graze along the trail.

In 1865, when Alexander Brizard and James A.C. Van Rossum purchased the firm of William Codington & Company, Codington was in the forwarding business. From this point it may be assumed the Brizard firm added a pack train service to the mines of the Klamath-Trinity area.

A notice in The Humboldt Times dated May 26, 1865 states: “Particular attention paid to Forwarding Goods to any part of the Mines. All orders will be filled with care and will receive prompt attention at the old stand of Wm. Codington and Company.” This store was located at the corner of Ninth and G Streets, and was occupied by the new owners. A corral was located just west of the store.

Mules are found listed in the Humboldt County assessment rolls for 1867 as being owned by A. Brizard. “There is something very pleasing and picturesque in the sight of a large pack train of mules quietly descending a hill, as each one intelligently examines the trail, and moves carefully, step by step, on a steep and dangerous declivity, as though he suspected danger to himself, or injury to the pack committed to his care,” said an eye-witness account in Hutching’s magazine. In Northern California, there were at least five thousand mules engaged in packing in 1856. The number was to grow as population and commerce increased.

Oscar Lord in the Humboldt County Historical Society yearbook for 1954, wrote:

The early settlers of Northern Humboldt, Klamath and Siskiyou Counties were supplied with provisions, furniture, and gold mining equipment brought in by pack trains. These trains usually consisted of from 30 to 40 mules, each carrying an average of 300 pounds. A bell-mare led the pack train. There was also a mule for each packer. The crew consisted of a boss packer, a packer for each 10 mules, and the bell-boy who doubled as cook, led the kitchen mule. During the trip the men subsisted on pancake bread, bacon and beans. “The three large trains operating in this area in the 1880’s were owned by Alexander Brizard, who had 125 mules; Thomas Bair, who had 60 mules; and William Lord, who had 75 mules.

Pack train routes, as Mr. Lord remembered them, were described in these words:

One of the old trails taken by the pack trains into the Orleans Bar country started at Arcata, then went to Trinidad, and northeasterly over the mountains by Redwood Creek near the homestead of the Hower’s, which was a stopping place for many years; then up the Bald Hills; through the Hooker ranch to French Camp; down into Martin’s Ferry; to Weitchpec and Orleans Bar. Another trail, which was used more than the trail by Trinidad, commenced a short distance east of Glendale; to Liscom’s Hill; down into the North Fork of Mad River; to Fawn and Elk Prairies; down into Redwood Creek at Beaver’s; to Hower’s, through the Hooker Ranch, etc., as noted above. A loaded pack train took seven days to travel the 78 miles from Arcata to Orleans. The return trip without a load took only five days.

Here, the Martin’s Ferry is occupied, crossing the Klamath River with a string of pack mules headed for the interior. The photo was by the girl photographers A. and Z. Pitt of Martin’s Ferry whose cameras saved a treasure of valuable history.

On the first page of the Arcata Union, Vol. 2, No. 1, July 30,1887, one finds A. Brizard advertising at the “Stone Store, Arcata,” with branch stores: Orleans, Willow Creek, Weitchpec, in Humboldt; Somes Bar, in Siskiyou Co., Francis and White Rock, New River in Trinity County.

Attention is called to packing:

Running my pack trains to above points, am prepared to furnish transportation to these or any points in the mountains on favorable terms. Goods consigned to me for transportation will be stored free in my fireproof building.

For many years the A. Brizard pack trains were loaded in corrals in town. Then the train was taken out of town about a mile on the Alliance Road, where time was taken to readjust the packs for the remainder of the trip.

Before the advent of the Arcata & Mad River railroad, freight was carried from Arcata to mountain destinations. Later freight was to be loaded aboard the trains. This cut down the distance considerably and saved the strength of the mules for the mountainous work.

According to a note found in the Blue Lake Advocate, dated April 18, 1891, this was the time when the new loading location came into use. Mrs. Eugene F. Fountain, Blue Lake historian, included this in her “The Story of Blue Lake” on October 6, 1955.

Mr. Brizard’s train under the management of J. Zeigler left Blue Lake Wednesday morning for Somes Bar, with a cargo for Martin’s Ferry, Orleans Bar and Somes’ Bar. This is the first train which left this spring and after this all of Mr. Brizard’s pack trains will start from Blue Lake.

Mrs. Fountain reported in a story she found in the Blue Lake Advocate, July 27, 1895, the fact the pack trains often returned with “pay-loads.” Sometimes they made special supply trips:

Every year A. Brizard’s pack trains make a few trips to Etna, Siskiyou County, where they pack a whole lot of flour from the mill there, to supply his stores at Somes Bar, Orleans, Francis and White Rock. The two trains in charge of Ed Scott and Weitchpec Ben, respectively, are expecting to go to the Etna mill in a few days. Mr. Brizard usually buys every year about 45,000 pounds of flour from that place.

When the Blue Lake Advocate celebrated its jubilee May 7, 1938, a story from the files for December 26, 1903 is featured: “THE PACKING SEASON OVER.”

The packing season from Blue Lake to different points in northern and northeastern Humboldt is now closed for the winter, A. Brizard’s train under the charge of Oscar Brown, has gone to winter quarters at Bald Mountain, while the other train, under Ed Scott, is making its last trip to Hoopa and Weitchpec. The faithful mules will be turned out for their winter vacation on Brizard’s Bald Mountain ranch, and in about two or three months packing operations will be resumed. Ed Scott, one of the best boss packers in Humboldt County, has decided to quit the business and from now on he expects to be employed for the Orleans Bar Gold Mining Co., at Orleans. Ed put in a good season last year, having been on the road and trail since February 15th, but he considers this kind of life as a little too hard for him, and hence his resignation.

At the end of the next season, February 20, 1904, the Advocate said:

Brizard’s pack mules, some seventy-seven in number, were driven from Hoopa to Bald Mountain, Saturday, for a change of pasture. Some thirty-three head, in charge of Domingo Bibancos, the old Chilean packer, were taken to Arcata Monday for a week’s stay, where they will be fed hay. The packing season will commence some time next month.

Mrs. Fountain wrote the mules were being loaded behind the A. Brizard store at Blue Lake. At times there were unavoidable mishaps such as this:

When leaving the freight yard with a load of shovels, one of the faithful mules turned its back too close to a window in the store building and as a result the long shovel handles passed through a pane of glass. The loss was charged to that particular mule’s credit with a little remonstrance on the side.

Here are some of the packers who kept the mountain routes and commerce alive. With the exception of Ben Billie of Weitchpec, upper left, they came from Mexico and South America. Not in the photo is Domingo Bibancos, probably one of the most famous of packers in northwestern California.

Besides Domingo Bibancos, another South American packer, was Sacramento Moreno. In 1881, in an advertisement, Brizard recognized his association, as the “Brizard & Moreno pack train.” This association remained until 1887, when Moreno sold his interest to Brizard. Moreno was in Arcata in 1873, when in March of that year, Edmond Le Conte sold the packer property in Arcata for $450.

Alexander Brizard was convinced he had the best pack trains, the best packers, and he did not hesitate to say so. In a letter on June 8, 1896, to J.T. Parsons of San Francisco, an official in the Red Camp Mining Company, Brizard wrote:

As to the transportation your company requires will say this is my line and flatter myself that I can handle in more satisfactory manner than anyone else in this section. Trust I need not refer you to anyone for my reliability and facilities to carry out any engagement. I refer to this for there are some with only a few mules who will offer to take all that is offered them, and do the work where and when they can or convenient.

I deliver goods beyond Cedar Flat and could not if the other route you mention is used. The goods then must go by rail to Redding thence to Weaver by team, 40 miles to North Fork of Trinity, by team about 20 miles, thence by pack mule to Cedar Flat, another 24 miles. It has to go through all these hands, each adding their charges. There is no regular pack train running between North Fork and Cedar Flat. You would have to have someone arrange terms for this additional transportation.

To show you advantages of my route, I will receive the goods f.o.b. Steamer Pomona from your city, marked ‘Diamond B’ Arcata, with added initial to desegregate from my freight. I will deliver to Cedar Flat, 2/4 cents per pound, provided of course packages are suitable for mule transportation.

His letter adds: “I have had 40 years experience in packing. Mined many years ago with a rocker at Cedar Flat.”

In another letter a few days later, Brizard told the San Francisco mining man: “It is six days from here to Cedar Flat — say eight days to be safe. If my pack trains are out, I can, if I know a few days in advance, arrange a train to pick up goods.”

On June 15, 1896, still writing to the Red Cap Mining Company officers, A. Brizard advised:

The mining pipe should be put up in 150-pound rolls not over, by 150 we can add here. Be sure not to forget the rivets, needed tools, as there is some distance to where these can be had, and in this there can be an expensive loss of time. It is the little things that are inexpensive, but are overlooked, nevertheless. Important to have indispensable good man to direct work on ground, and remind you that the most efficient helpers, good ordinary laborers, are not always available in those parts. I offer this as a suggestion.

Although there are many stories in existence of pack train mules owned by other operators, carrying five or six hundred pounds, A. Brizard, would never permit abuse or overloading of his animals. In an excerpt from a letter concerning shipment of mining equipment, Brizard said: “Will not agree to take freight till I see it, as I can’t tell what mill and pipe will be. Some think a mule can pack anything. I know they cannot.”

During this period of packing, tobacco was an important ingredient for both packer and miner. In a letter dated, October 8, 1896, A. Brizard wrote:

Yours of 3rd received. In regard to quantities of tobacco used. Some months use 300 pounds to 500 pounds according to business. I never order less than 150 pounds or 200 pounds at one time. ‘Battle Ax’ has been looking up and I now sell quite a quantity, and seems to be improving. Whenever ordering never send me less than a 100-pound lot of same.

You must understand my business, that at certain times of the year I handle large quantities of tobacco, according to the season. Some months four times as much as others. I have to pack all my goods by mules, so have to depend on the weather …

Buying of mules for the pack trains was a job A. Brizard himself undertook, which he so states in a letter to J.W. Stout of Klamath Falls, Oregon:

I have just returned from a trip to Round Valley where I purchased all of the mules that I required at a very low figure, as mules are plentiful there just now and can be had at any price. I do not know of anybody in this part of the country who you could make a sale to. I have on hand over 150 head, some of which I would be willing to sell very cheap …

There was always the weather to contend with, as A. Brizard indicates in this portion of a letter to W.J. Wiley, San Francisco, on May 10, 1896: “First day of decent weather. Had been raining, delayed pack trains. Two of mine delayed four days this side of Redwood Creek. Could not cross.”

Tired, pack animals and their loads arrive at Orleans. Knowing it was the end of the journey, some of the mules stretched out for a rest before unloading.

On September 13, 1896, the Arcata & Mad River passenger-train plunged through a suspension bridge over Mad River. The drop of 35-feet, killed seven passengers and injured many more. A. Brizard wrote in a letter to the Red Cap Mining Company he was both shocked and horrified by the tragedy. The victims, he knew, as friends and customers. Too, he pointed out, there would have to be some changes in getting freight to Blue Lake, since the train had been used carrying Brizard freight. This would now be delayed until the bridge was rebuilt. He announced he would immediately start moving freight, by wagon to Blue Lake. Apparently this was satisfactory with the mining people.

The A. Brizard pack trains carried all types of freight, merchandise for the branch stores. There were often interesting requests, such as this one by A.F. Risling, manager of the Orleans store on November 19, 1892: “… Send by train one large demijohn. Please have it filled with Greenwald whiskey and address Samuel Bell, and also one gallon for Charles Bristol. I should like to get up a gallon myself for a few personal friends for Christmas and assure you no harm will be done.” The word “harm” was given additional assurance with an underline.

Old-time packers knew how to overcome thirst, if whiskey was in the manifest. By driving horseshoe nails into the keg, then withdrawing it, they were able to encourage enough leakage to acquire the “needed spiritual” reinforcement, we are told. Ernest C. Marshall of the Bar Vee Ranch at Hoopa, viewed a picture on a calendar issued by A. Brizard, Inc. It showed a typical pack-train readying to leave Blue Lake. Two of the packers in the picture were Bell-Boy Bud Carpenter, and Ben Bille.

In reminiscing I cannot help but turn back the pages of time to my youthful years,” the old-time packer wrote in a letter to “My Children”, “when the scene was common and the only means of getting ware to the most remote areas in the mining regions …

The mule trains of that era consisted of from 25 to 50 mules, though at times on urgent orders two mule trains would merge, making the train capacity 75 to 100 mules. A crew for 25 miles consisted of around 3 men. There was a bell-boy, second packer and the boss packer, or foreman. The duties of the bell-boy included the culinary department. He requisitioned all food and utensils, with the boss packer’s approval, needed to prepare meals and make the lunches. He led or rode the bell-horse ahead of the pack train. It was impossible to leave a mule behind, once the bell-horse started forward on the trail.

The salary of the bell-boy was $30 per month, including found (‘found’ means board). The duty of the other packers were general; unloading the packs at the end of the day, unsaddling and feeding or pasturing the mules as they depended entirely on forage along the trail. Therefore, camps were always made where there was plenty of feed. They picketed the bell-horse and the mules never strayed very far away.

The day started long before dawn, with the bell-boy busy around the camp fire getting breakfast for the crew, while the other men brought in the mules to saddle and load for the day’s trek.

They left as soon after dawn as possible, traveling not more than 15 to 20 miles per day, to give the mules more rest and foraging time at the end of the day.

The second packer rode in the middle of the pack train to better watch the mules so they did not bunch up or shove another loaded mule off the narrow trails, and to see that the mules were riding straight up, because sometimes over the narrow trails a lop-sided load could throw a mule off the trail, killing the animal. The second packer’s pay was around $35 a month, with found. The boss packer rode behind the train, keeping an eye on all the mules. He was responsible for the care of the mule train and his men, and of the safe delivery of the cargo in his care. His salary ran around $40 to $45 per month, and found, depending on the number of mules in his train. He had to maintain all the equipment, keep the mules well shod, make arrangements for the feed of the animals along the route. He had to know the carrying capacity of each mule, which varied from 300 to 400 pounds. There were only a few mules that could carry a top pack, such as a cook stove or bulk loads weighing 300 pounds or more.

All loads were carefully packed and roped together at the starting point, or warehouse, and placed in strong burlap bags for side packs. These weighed from 150 to 200 pounds each making the loads for the mules from 300 to 400 pounds. The loads were placed in long rows, ready for the next day at dawn.

The life of a packer on a mule train was a rugged one. He had to be able physically to endure the cold weather, the rain, snow, sleet,and frost,and the terrible windstorms of the high mountains. Crossing swollen streams entailed the use of canoes, later swimming the mules across, to again load and resume the journey.

Regardless of the weather, the packers knew that for their protection from the weather they had to pitch their tent for the night. They also had to dry out their blankets as best they could under these weather conditions. Deep trenches had to be dug around the tent to prevent the water from running into it while the men slept. Bedding consisted only of blankets and canvas spread on the ground.

Each packer had a leather canteen for carrying his personal belongings, lunch and a leather blind that had to be used in the loading and unloading of the mules. The blind was placed over the eyes of the mule, and the end straps over the ears, holding it in place. Some of the mules were outlaws, never taming, regardless of heavy loads and work.

“You will note that the loads on the mules have two different hitches,” Mr. Marshall says, referring to the photograph. “The most generally used, the diamond hitch and barrel hitch. I had the occasion of participating in the loading out of the last pack train that was operated by A. Brizard, Inc. when I was employed by the company as a clerk at Hoopa. That was around the year 1920.”

Somewhere in Humboldt County there should be a bronze statue dedicated to the faithful pack mule-servant and slave.

When California’s first commercial oil was taken from the Mattole Valley, it was on the backs of pack mules to Leland Stanford at his San Francisco refinery. Wool was shipped from the Bald Hills to Humboldt Bay; from the mountains of south county to Shelter Cove, and from Blocksburg to the waiting steamer — all aboard pack mules.

There were butterfat trains from Bear River and the Mattole Valley for Port Kenyon and the San Francisco market — long trains working along the trails with many duties to accomplish in those worrisome times of settlement. The same trains brought settlers and their belongings. Without them — the pack trains — what would our history have been like?

The store at Weitchpec gets its cargo of necessities as the mule train arrives. Similar trains traveled to White Rock and other trading posts scattered throughout the inland area.

###

The story above was originally printed in the September-October 1982 issue of The Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society, and is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE