Screenshot of Tuesday’s Eureka City Council meeting.

###

Dozens of desperate community members gathered in Eureka City Council chambers on Tuesday evening to call upon city officials to do more to address the city’s shelter crisis.

The idea behind the informational workshop was to encourage community members to bring forward creative solutions to the shelter crisis and provide residents with the requirements necessary to create authorized encampments with tent structures of tiny homes on private property within city limits. Over the course of the three-and-a-half-hour meeting, those in attendance urged local organizations and city officials to act with urgency to prevent more deaths in the unhoused community. Some advocated for the repeal of the city’s anti-camping ordinance, while others called for the shelter crisis to be treated as a bona fide emergency, comparable to a wildfire or other natural disaster.

Eureka City Manager Miles Slattery began the discussion by outlining several housing strategies the city has already explored and/or implemented in the last decade, including rotating encampments and expanded sheltering options through Betty Chinn’s Blue Angel village, St. Vincent de Paul and the Eureka Rescue Mission. The city is currently working with Betty Chinn and contractors to develop the Crowley Site as well, Slattery added, referring to a city-owned lot on Hilfiker Lane, at the south end of town.

The City of Eureka passed an emergency shelter resolution back in 2016 and a subsequent emergency shelter ordinance in 2021 in an effort to expedite immediate shelter options for those in need. However, emergency shelters are only allowed in some areas of the city, said assistant planner Millisa Smith.

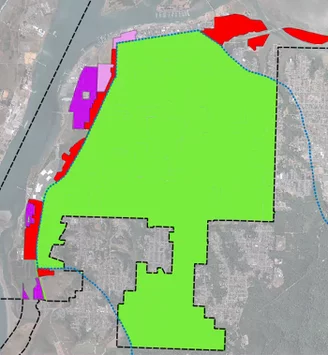

“The city’s zoning code divides the city land into zones and includes specific rules and regulations for each zone,” Smith explained. “It is important to note that because part of the city is in the coastal zone, we have separate coastal and inland zoning code regulations.”

Emergency shelters are allowed in the red and purple portions of the map to the right under the Emergency Shelter Crisis Act. For instance, the Hinge Industrial Zone — near the intersection of Broadway and Fourth — allows emergency shelters in buildings and open spaces without a use permit, but the shelters cannot be located within 1,000 feet of a school or within 50 feet of another shelter. Other portions of the coastal zone would require a coastal development permit and would be subject to environmental review, Smith said.

“Any city-owned or controlled site can be used as an emergency shelter,” she continued. “If a property owner wanted to use their property as an emergency shelter they would have to enter into a lease agreement with the city allowing for any parcel in the inland portion of the city to be an emergency shelter, as seen in green on the map. … Local zoning and planning standards do not need to be adhered to but basic health, safety and welfare standards must be met [and] environmental review is still required.”

‘Our Compassion Has to Come Out’

More than two dozen community members spoke during the public comment portion of the meeting. Several commenters shared their ideas for potential encampment sites and setups, but the vast majority of speakers emphasized the need to act quickly.

“The emergency is happening tonight,” Eureka resident Scott Graham said. “The emergency was last week. The emergency was last year. When can we expect this to happen? Is it going to, you know, just languish somewhere [while] people just mull it over and [it] doesn’t happen? … Something, somewhere, somehow, things have to happen. Our compassion has to come out. … Those people out on the streets are suffering more than any of us in this room. We should really be trying our best to help them and give them a lift up.”

Unfortunately, Slattery said the city “can’t really tell” how long the process will take. “I can tell you this: If we had a program in place that was approved by council, this could happen as soon as another council meeting, as long as the provisions are in place to meet the guidelines that we just described,” he said.

Eureka resident Caroline Griffith asked if the city would consider suspending its anti-camping ordinance so people can be “in a settled, safe space” while a more permanent encampment is established. The ordinance currently prohibits camping anytime in Old Town/Downtown, Henderson Center, the Waterfront and the Northern Gateway districts, in city parks, the golf course and within 75 feet of public trails. It also bans camping anywhere in the city during daylight hours, except for when it is raining, snowing or below 40 degrees.

“Technically could happen,” Slattery said. “I think, from staff’s perspective, we’d have the same concerns about the rotating camp and not having any oversight. I think that would be a council decision, but it would be extremely difficult to manage.”

Griffith also asked if the city would consider a vacancy tax or an occupancy incentive to motivate property owners to fix up and fill empty buildings. “I moved here six years ago, and throughout the course of wandering around the City of Eureka in that time [I have seen] buildings that the entire time have sat vacant,” she said. “Whatever we can do to make sure that those are actually occupied would be amazing.”

City Attorney Autumn Luna said the city “has discussed some kind of tax on absentee owners” and expressed interest in looking into the matter further. “But I will say that it doesn’t guarantee that those buildings will then be occupied,” she cautioned. “Samples of that [strategy] from other cities show that many owners will choose to just pay the tax, so we are aggressively pursuing other options with those buildings that could potentially be put into receivership, fixed up and come back into the housing stock.”

Slattery added that the city is in the process “of doing a vacancy incentive slash tax” that will be reviewed by the council in the coming months.

Manila resident Sequoyah Faulk urged the council “to consider pushing for properties to be allocated and prepared” for tent or tiny home encampments and proactively seek organizations “that can make proposals that would fit those sites because one of the biggest hurdles is location.”

He and his father, retired Humboldt State University professor Dan Faulk, started building tiny houses a number of years ago. In 2021, the pair worked with Councilmember Leslie Castellano to place two tiny homes at the St. Vincent de Paul site in Eureka. Just last week, Faulk released an 18-minute documentary called “Humboldt is Home” to highlight and humanize members of the local unhoused community.

“There’s not an ‘all of the above’ approach that’s going to solve this situation,” Faulk said. “From my experience [in] meeting individuals who are experiencing homelessness, there’s as big of a variety of backgrounds and circumstances as people who are housed. … I think we need to hit it from every angle and don’t crumble in the face of NIMBYism and be willing to not have things be perfect, but just do what’s going to be looked back upon in 10 years as the thing that set Eureka on the right course, as opposed to taking the easy path that just kicks the can down the road.”

Area resident Mike Price expressed “some concerns with the proposal” and urged the city to address the drug and mental health crisis before putting people into encampments.

“I also have some concerns about enforcement mechanisms,” Price said. “What are we going to do to ensure that this doesn’t evolve into what our unsanctioned homeless camps look like right now? … If we have sanctioned homeless camps we’re gonna have harm reduction there. We’re gonna have needles there. Who’s cleaning it up? Who’s administering the Narcan? Who’s ensuring public safety? Who’s ensuring that this doesn’t devolve into a situation that we’ve had over and over again?”

Slattery reiterated that, as a part of the council’s approval process, guidelines would be established for each encampment. He noted that there was a lot of concern surrounding the establishment of Betty Chinn’s Blue Angel Village but said “those concerns never came to fruition [and the program] has been extremely successful.”

Doris Grinn said she recently moved back to Humboldt County after spending a number of years working in the Sierra Nevadas with the U.S. Forest Service. During that time, she said she had spent time learning about the “fire evacuation camp model” and implored the city to treat the homelessness crisis as an actual disaster.

“It’s got portable toilets, portable showers and portable laundry facilities,” she said. “It has covered cafeterias and kitchens [where] they’re able to feed people. They’re able to help [people] with emotional stuff. There are places for children. There’s actually an assessment of people’s skills, you know, can they help? Can they work? What can they do? … The fire camp model, I think, is a good plan for a homeless camp. … We know the format and we know what works and what doesn’t work for large amounts of people.”

Lisa Gust, a homeless outreach worker with the county, said she has lived in Humboldt County for the last six years “and not one thing has changed.”

“I want to know what’s going to happen when we leave this meeting,” she said. “People are dying. People are out there in the freezing cold. There’s no place for them to go. If they have animals, they’re just SOL. If they’re on drugs, they’re just SOL. If they’re too mentally ill, nobody will take them. There’s no place for them to go. The gentleman who died at the bus station last night was one of those [people] that there was no place for him to go. He was destined to be on the streets for the rest of his life. We tried to help him, but it didn’t work. So guess what? Now he’s gone.”

Gust urged residents “to do more to help our own people,” adding that bureaucracy and “stupid government regulations” are only preventing communities from helping struggling individuals.

The last commenter of the evening was Dotti Russell, a relative of the man who was found dead at the bus stop at Third and H Streets in Eureka on Tuesday morning. In a heartbreaking plea, Russell asked over and over “How did this happen?”

“How did it happen that my nephew, who never hurt anybody, was alone and cold and died at a bus stop in Old Town?” she asked, her voice wavering with emotion. “My nephew passed away in Old Town. Why? Because he was told that the services were better [than in Southern Humboldt] and he should go to where the services are in Eureka. … I know you really want to do the right thing and he just followed the information he was given, but how did this happen?”

‘The First Step is Making a Plan’

Following public comment, Councilmember Renee Contreras de Loach asked Slattery to explain “the obstacle in 2020,” a point that had been referenced several times throughout the public comment period. Slattery explained that the city had been working with Affordable Homeless Housing Alternatives (AHHA) over the course of four months to create a sanctioned encampment but at the eleventh hour, AHHA backed out due to community response.

“We had many many meetings with board members, with our previous police chief, [with] Sgt. [Leonard] La France, at the time,” he said. “Community members came to a consensus –from my understanding – that we were ready to move forward and go to council and then it was decided by AHHA not to move forward with the plan.”

Councilmember Leslie Castellano jumped in to add that “relationship-building can take some time,” noting that “the conversation isn’t necessarily over or anything like that.”

Contreras de Loach also asked about the city’s vehicle abatement program and whether the city would be willing to provide a sticker or a permit to stick on their dashboard to inform the abatement team that the vehicle is being used as a shelter “so it isn’t hauled off.”

“We get a lot of abandoned and dumped vehicles in my neighborhood and they are legitimately, I think, dumped and abandoned because it’ll sit there for days with no one anywhere near,” she said. “But if somebody is using [their vehicle] as a shelter … I don’t want us to be impounding vehicles if someone is not necessarily using that as a vehicle, but that is a shelter.”

Slattery noted that the abatement process is largely complaint-driven, adding that the city “doesn’t do vehicle abatements just because they’re sleeping there.”

“We do vehicle abatements if they’re unregistered and … we have to notify them if they’re on the road for 72 hours that they will get abated,” he said. “We don’t go and abate their vehicles because they’re sleeping in it. As far as a permit system where you can say, ‘Yes, they can stay here if they meet all the other vehicle codes,’ that is something that we could do. But the 72-hour thing would probably come into play … because that’s state code.”

Castellano said she empathized with the community’s calls for creativity and expediency, noting that different things work for different people and multiple solutions will be necessary moving forward. She suggested a three-part approach to “create a pathway to success.”

“The first step is making a plan,” she said. “We could host a workshop for anyone interested in collaborating on making not just one plan but maybe, like, five plans that could be successful. The site is the next step. We host a collaborative workshop to find sites. … I would like to see the city designate at least one site, you know, in good faith. … And then, I guess the third part would be working with people to get grants.”

Castellano added that there ought to be “a time signature” applied to the encampment proposal process to really push the matter forward. “I understand that this is an emergency that’s happening now and I want to honor that,” she said. “The longer we wait, the more people are in life-threatening situations.”

Councilmember G. Mario Fernandez agreed that the city should view the shelter crisis “as a disaster,” but acknowledged that the city would not be eligible for state or federal relief funding in the same way as a natural disaster.

Fernandez also asked about the scale of Eureka’s homeless crisis: How many unhoused individuals are currently living in the city? There were 498 unsheltered individuals identified by county staff and volunteers in Eureka during the 2022 Point in Time (PIT) Count. However, the City of Eureka only identified 250 individuals as a part of the Eureka Police Department’s Homeless Survey for 2022.

The actual number “is somewhere in that ballpark,” Slattery said, noting that the city has helped local shelter providers to bring the total number of shelter beds to approximately 150 in the last few years.

Fernandez asked if any of the local shelters provided space for people to leave their belongings, if there is kennel space for dogs, or if people that are under the influence of alcohol or drugs can seek shelter.

Slattery said most shelters offer space for people to store at least some of their belongings but none of the local shelters offer kennels for dogs. He added that it is a “big misnomer” that shelters turn away individuals who are under the influence. “Can you do drugs in [the shelter]? No. Can you come in inebriated or on drugs? Yes.”

In previous conversations with the Outpost, the Eureka Rescue Mission has confirmed that shelter staff breathalyzes newcomers and people they suspect to be under the influence. The shelter’s website notes, “You must be sober. We use a breathalyzer.”

Fernandez also asked about the possibility of using the Eureka Municipal Theater or the Eureka Vets Hall as temporary shelter locations. Slattery noted that as the veteran’s hall is not owned by the city, that would be a county decision. As for the Muni, Slattery said it “is partially leased” for special programs. “If we were to do that, we wouldn’t have a Hoopsters program,” he added.

Councilmember Kati Moulton asked about some of the requirements associated with a tent encampment, and whether the tents would be elevated off the ground. Slattery said the tents would be elevated, but said that could easily be done by placing the tent on a palette. She asked if the city would be able to provide future residents of the encampment(s) with tents, heating pads and bedding.

“The city doesn’t have the funds to do stuff like that,” Slattery said. “If we were to do [that] and … if we were to go after a grant for something like this, we would want it to be more permanent. … I’m sure we can assist in some way. I think that if we have an approved project and it’s ready to go and we have a location, it’s not going to happen overnight, but I don’t think that funding is going to be difficult to get.”

After some additional discussion, Castellano asked if her fellow council members would be interested in pursuing the three-part strategy she suggested earlier in the meeting but Luna interjected, noting that the workshop was billed as informational and any further action would be inappropriate. Castellano agreed to bring the item forward as a future agenda item during the council’s next meeting on Tuesday, March 7.

A full recording of the meeting can be found at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE