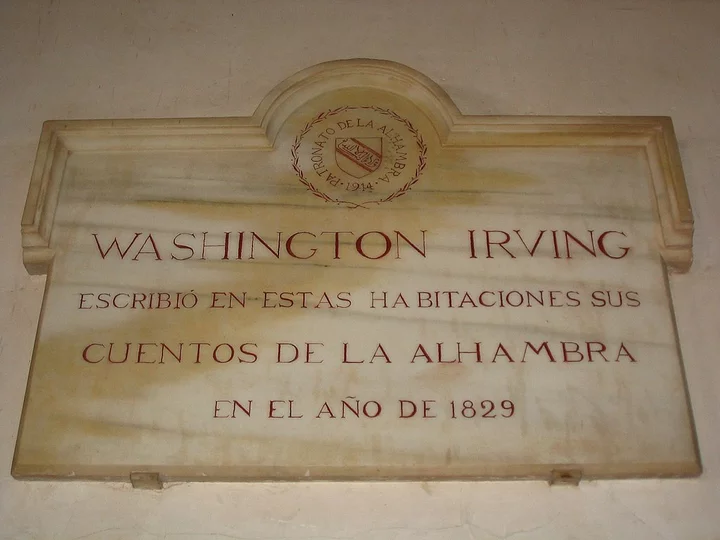

A plaque on a wall of Spain’s Alhambra Palace celebrates the American writer Washington Irving (1783 –1859), who wrote his best seller Tales of the Alhambra there in 1829. Construction of the palace-fortress, located in Granada in the heart of Andalusia, Spain, was begun nearly 800 years ago. It’s the finest example of Islamic architecture that I’ve seen, well worth a day trip from Madrid in the north or Malaga in the south. Go early! When I visited in 1983, I was one of only a dozen tourists, but I hear it’s now crowded, especially at weekends.

One corner of the Alhambra. (Barry Evans)

Plaque acknowledging where Washington Irving wrote “Cuentos de la Alhambra,” Tales of the Alhambra, in 1829. Javier Carro, Creative Commons license, via Wikimedia.

I’d barely heard of Washington Irving back then, not having been raised in the U.S., where I understand such classics as Rip Van Winkle and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow are essential reading for young people. My first real encounter with Irving was when I was researching the myth that Christopher Columbus was warned that the world was flat and he might sail off the edge of the world. The first record I ever owned (remember 78s?!), a present from my sister in 1951 (I was nine), cemented the facts in my mind. Guy Mitchell sang:

Queen

Isabella she gave heed

Said

go buy the ships you need.

Take

my jewels but travel slow

‘Cos

you might fall down to the world below.

I blame Washington Irving. Before his stay at the Alhambra, he lived in Madrid, where he wrote A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, published in January 1828. According to Wikipedia, it went through 175 editions before the end of the century. In it, Irving spins the yarn that scholars believed in a flat Earth in the medieval world of Columbus’ time, and that we should thank the Genoese navigator (who was actually a conquistador, in the worst sense of the word, once he reached the Americas) for proving that the world was round.

Not only was the shape of the Earth well known to the ancient Greeks nearly two thousand years before Columbus “sailed the ocean blue,” but they even knew the approximate size of it — to a better approximation than that assumed by Columbus, who confused the units used by the Greeks. Around 200 BC, the head of the Library of Alexandria, Eratosthenes of Cyrene, estimated Earth’s circumference to within a few percent of the actual value. (Probably — historians are unsure about the modern equivalent of his unit of length, the stadion.) He did this by famously measuring the difference in angles of shadows cast by vertical rods in Alexandria and Syene (modern Aswan), knowing the distance between them.

So yeah, Columbus knew the Earth was round, even if he did underestimate its circumference (by a whopping 33 percent — hence “Indians”). And Washington Irving knew that he knew, but he was a writer, a teller of tales. Someone who practically invented the genre we now call “historical fiction.”

CLICK TO MANAGE