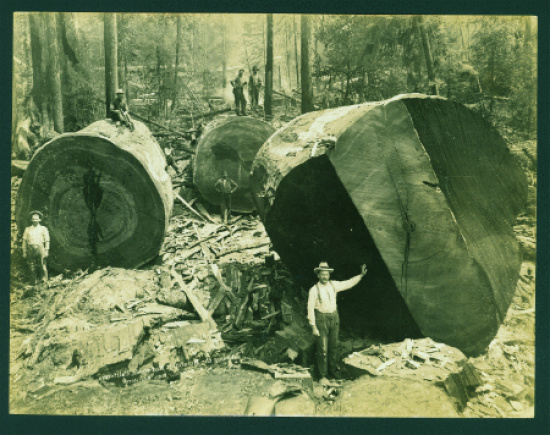

Trees such as this may have stood for a thousand years or more prior to Euro-American incursion. (Photo courtesy of the Humboldt Historical Society)

The following piece is a guest article by Kyle Keegan. It was first printed in the Trees Foundation Newsletter. It is reprinted here with their kind permission. In a society that sees the effects of diminishing streams and increasingly damaging wildfires, the more knowledge we can gain about the systems that affect them, the more we can act to prevent some of the damage.

Here is a link to Restoring the Sponge part 1

A Crisis of Culture

“The march of improvement is westward, its destiny `to rule the spacious world from clime to clime’ cannot be gainsayed; while on the shores of the Pacific the same mighty power `shall every field explore, Trace every wave and culture every shore.’”

Alta California, 1850

In 1850, the settlement of Eureka, which was sparked by the Gold Rush, signaled the beginning of the most radical change experienced by the land of the North Coast since the last Ice Age. The waves of environmental destruction that followed the arrival of the first early settlers (which still continue to this day) were merely symptoms of a much deeper cultural malady. These invaders imposed an entirely new set of ideologies, belief systems, and cultural values on the surrounding ecosystems and its native inhabitants.

The indigenous land-based cultures that had persisted on the North Coast for millennia prior to Euro-American incursion can be described as “kincentric,” a term coined by Native American ethnobotanist and restorationist, Dennis Marinez. In other words, native cultures of this region and beyond created belief systems or cosmologies that held humans as being merely a part of nature; where the elements that comprised the landscape (water, trees, animals, etc) were seen as kin. Leaf Hillman, who writes of the Karuk’s mythic cosmology, expresses this mindset clearly:

“All of us at the beginning of time were spirits. At the transformation, some spirit people become human beings and some become rocks and fish and trees and water and air and mosquitos and all those other things. That right there is the most fundamental principle that everything springs from, because that establishes our relationship to this place. We began at the same place that everything else did. We were all spirit people, all equal…we were all related because we were all spirit people. The transformation just meant that people took on different forms, different life forms, so that means that if the spirit becomes a tree or a rock, that’s a life form.”

It was this “kincentric” view of the land being replaced by an “anthropocentric”, or human-centered view of the land that set into motion the ecological devastation that followed. Anthropocentric belief systems are based on dominion and the control of Nature, and are centered on the rights and freedoms of the individual.

Numerous first-hand accounts written by early settlers during the Gold Rush era made three clear assumptions about California’s natural environment. Kat Anderson in her book, Tending the Wild writes:

“First, they assumed that its diverse natural resources lay idle, untapped, and uncultivated by lazy Indians and Californios. Second, they thought Nature’s abundance and diversity were going to waste, and they had a God-given right to use them for profit. Third, they viewed the resources of California as inexhaustible.” It was this endless frontier delusion, coupled by a belief system that justified the commodification of Nature for profit, that would set the stage for the first wave of attacks on North Coast ecosystems and its native peoples.

The Replacement of Localized Economies with Export-dependent Economies

Also of importance in understanding the sequence of events that have brought us to this current point in history, is the acknowledgement of what once were highly localized, and diverse land-based economic systems being replaced by—export-dependent, resource extractive economic systems.

|

|

The Indigenous people’s land-based economy was kept in balance by cultural ideologies and mysticism that practiced and upheld the virtues of self-regulation and the willingness to accept feedback from the surrounding environment. These ideologies were passed on and strengthened through stories and songs and became a requisite value to instill in each succeeding generation in order to assure their continued quality of life and survival. The resilient localized economies were based on: maintenance and support of biodiversity, regional self-reliance, personal and communal responsibility/restraint, appropriate technologies, and by creating cultures of place.

With the early beginnings of globalization and the industrial revolution came the erosion of localized economies, and with it followed the destruction of the land in which both the local economy and its people relied upon. Export-oriented, resource-based economies are incompatible with ecological soundness; since unlike Nature, energy (nutrients, carbon, minerals, life) flow linearly away from existing communities. The export-oriented economy relies upon the continuous extraction of local resources while becoming dependent and vulnerable to the fluctuations of global or domestic markets. By embracing this system, a community and culture relinquish control of their destiny.

The export economy exists only through perpetuating that similar unaccountable systems be carried out in far off lands; since most resources needed locally must be imported to the now dependent region. In this manner, natural communities are transformed into commodities. Thus, the environmental impacts that we find ourselves confronting today are merely symptoms of social/economic systems created by our perceived separation from the natural world.

In the following paragraphs we will follow the history of these symptoms and how they have impacted the “sponge” on the North Coast. (The sponge is defined as the ability of a watershed to receive, hold, and retain in-coming precipitation, while then slowly releasing that water over time to support healthy stream flows.)

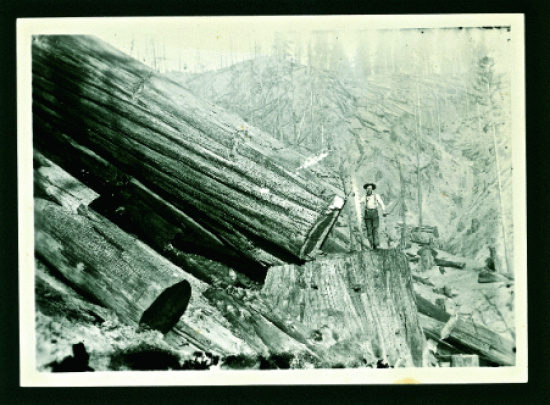

| Ox-teams such as this hauled logs over “corduroy roads” which were often constructed directly in stream channels. |

| Photo: courtesy Humboldt County Historical Society |

Gold is what enticed the first new cultures to settle the North Coast. By the close of 1850, every major watershed in the Klamath-Trinity basin had been prospected and “panned out”.(5) By 1851, there were possibly as many as 10,000 miners working in the Klamath-Trinity river system.(5) In the decades to follow, the entire Klamath-Trinity basin and its tributaries were literally disemboweled and left in rubble. Stream-side mountains were liquefied in the search for profits. The mindset behind this madness was exemplified succinctly in Hutching’s California Magazine in 1857:

“The MINER: He turns the river from it’s ancient bed, and hangs it, for miles together, in wooden flumes upon the mountain’s side, or throws it from hill to hill, in aqueducts that tremble at their own airy height; or he pumps a river dry, and takes its golden bottom out. He levels down the hills, and the same process levels up the valleys;…he pounds the rocks of the mountain into dust. No obstacle so great that he does not overcome it; “can’t do it” makes no part of his vocabulary.”

Eventually the “rush” was exhausted, and the thousands of faces who had arrived to strike it rich either turned to embrace another extractive endeavor, or moved on.

The Mass Removal of Carbon

“At every available point for shipment stands a saw mill turning trees to lumber, furnishing employment for labor and investment for capital.”

An early historian, 1881

Only eleven days after the founding of Eureka in May of 1850, redwood logs were being loaded onto ships and sent south to San Francisco—signaling the birth of the North Coast’s first export-driven, carbon-based economy. Four decades later, the North Coast would have 400 saw mills in operation. The hunger for the forests went through many cycles: redwood for shingles, shakes, fenceposts, wine stakes and logs—the tan bark boom—then Douglas-fir, and each year word spread further across the continent and beyond, with people coming and going by the thousands seeking quick profits from the land’s stored capital. As technology advanced, so did the logging methods, and with every successive wave of settlers came the loss of more ancient forest to speculation. After World War II came the bulldozer—now it would be a war on the land.

| Centuries of stored carbon were removed and exported away to distant lands. |

| Photo: courtesy Humboldt County Historical Society |

The entire North Coast forest organism was under attack, and watershed by watershed the tapestry that had taken thousands of years to be intricately woven was experiencing a mass unravelling. The region-wide removal of old-growth forest cover sent a cascade of impacts throughout the entire system. With the loss of the ancient trees that blanketed the land, came the loss of the tight cycling of carbon and nutrients. The forests were now unable to protect and feed the soil life and with this loss of bioregulation—the biological dam was opened—sending stored nutrients and minerals out of the system, and towards the ocean.(2) The loss of forest cover forced soil organisms to turn on stored carbon (humus) in the soil; oxidation of soil carbon increased; the entire structure, composition, function and process of the forest ecosystem

was altered.

With each passing storm, and every hot, dry summer, the wealth of the land was being diminished. No longer could the forest sponge effectively receive and hold the winter rains, and no longer could the summer fog coalesce on the outstretched arms of the fallen ancient trees. The climate was changing—and the now hot, dry summers—baked the once cool, and forested landscape.

With each winter season the return of heavy rains induced landslides, gullies, debris torrents, and mass wasting. Over-land flow and the loss of infiltration and forest interception led to swollen, chocolate colored rivers choked with centuries of judiciously stored topsoil.

Compaction of the Living Soil

The living soil became damaged and compacted by an array of imported machinery. The bodies of ancient trees were cabled, yarded, and dragged across—up—over—and—through landscapes. Soils compressed by bulldozers, skidders, and other heavy equipment were less able to absorb in-coming precipitation, and the subterranean ecology was altered by both compaction and the loss of forest protection.

The cut-over and compacted land now opened to the sun and driving rains experienced a shift in its biology both above and below ground. Interdependent links were broken. Mycorrhizal fungi which depended on the trees for their energy were severely diminished—so followed the Northern Flying Squirrel which depended on the truffles produced by the fungi—along with the Spotted Owl who fed on the flying squirrels—and so went the Martens, Fishers, Pileated Woodpeckers, Red Tree Voles, Marbled Murrelets, and Varied Thrush—now forced to seek new home places, or perish.

Overgrazing and its Effects on the Sponge

“How large a ranche have you, sir?” I asked. “One hundred and sixty acres,” he replied. “How many sheep have you?” “Four thousand or more.”

Warren B. Johnson (The road between Alder Point and Bell Springs 1882)

The new settlers had arrived with a diversity of exotic animals, plants, and seeds to help establish their culture. Exotic weed seeds introduced by both early Spanish explorers and Euro-Americans rapidly began to colonize North Coast lands. The most pervasive and aggressive of these exotic invaders were annual grasses. With the introduction of foreign livestock, the landscape quickly began to be transformed. Overgrazing and overstocking of the land began the early processes of erosion, soil compaction, carbon loss, and the alteration of plant diversity and composition.

North Coast prairie ecosystems had co-evolved with native mule deer and elk being moved through the system by both animal and human predators for millennia prior to Euro-American arrival. The continuous dispersal of the herbivores over large areas helped to build, rather than degrade topsoil. As the animals browsed the native perennial grasses and forbs, the roots would die back leaving carbon (humus) stored deep in the soil layers. The brief disturbance of the soil caused by the browsing and movement of narrow hoofed ungulates, as well as periodic low-intensity ground fires, maintained and supported one of the most diverse prairie ecosystems on the planet.(8)

Early settlers saw the grasslands as inexhaustible and would often place numbers of livestock far beyond the carrying capacity of the land. This had dire consequences for the land’s ability to hold and store winter rains. The wide, flat hooves of horses and cows compacted the fragile soils. The overgrazed land became vulnerable to surface erosion; the pores of the soil stomped into dust in the summer months became clogged and impervious when exposed to heavy winter rains; water sheeted over the landscape taking with it centuries of soil building processes. The earth, now exposed, was easily colonized by exotic annual grasses. Thus, began the landscape-scale conversion of perennial grassland systems into annual systems.

Annual grasses are hungry for water and nutrients, and with their shallow root systems, store significantly less carbon in the soil than perennial grasses. With the conversion of native prairies from perennial to annual systems, also came a change in the soil community. Perennial plants actively grow and photosynthesize throughout the year, producing exudates (carbohydrates/sugars) that feed soil life. Perennial grassland soils have a higher fungi/bacteria ratio, versus annual systems which are bacterially dominated. Mycorrhizal fungi produce glomalin, which recent studies suggest may contain 1/3 to almost a half of the carbon that is present in healthy soil ecosystems.(4,10)

Also of significance, annual grass invaders store most of their carbon above ground, and with their shallow root systems, lose most of their stored carbon to fires. Conversely, perennial grasses which co-evolved with low-intensity ground fires have the ability to store large amounts of carbon deep underground, safely protected from fires passing through

the system—thus keeping the prairie sponge intact.

| After a century of logging, the Christmas flood of 1964 set loose thousands of years worth of soil building processes. |

| Photo: courtesy Humboldt County Historical Society |

The historic floods of 1955 and 1964 delivered yet another violent blow to the already wounded North Coast ecosystem. Debris torrents scoured many upland streams and creeks down to bedrock, disconnecting watercourses from their floodplains and opening up inner gorges to the hot sun. The now gutted, and deeply incised channels would bleed stored groundwater from surrounding hill slopes, hastening the flow of water out of the upper catchments.

The land, denuded of its old growth, was unable to replenish the supply of large woody debris to stream courses. This large woody debris had created natural check-dams and in-stream terraces that functioned to slow down and increase the residency time of water, sediment,

and nutrients within the system.

Abandoned skid and haul roads that had mostly laid silent for years, suddenly came alive with the torrential rains—unleashing a flurry of hydrologic schizophrenia on the landscape. Roads became watercourses, and water flowed with an energy and direction on the land that had not yet been experienced since its conception—diversions, gullies, landslides and more debris torrents followed.

The loss of the upland’s capacity to mitigate storm energies exacerbated the destruction of the lowland floodplains. Many of these fertile flatlands had been converted from old-growth riparian forests to farming and grazing lands prior to the 1955 and 1964 floods. During the flood events, main-stem rivers experienced radical changes as an unimaginable mass of debris, sediment, and water inundated the lower systems. Entire riparian zones were wiped out causing changes in floodplain connectivity, and the continued pulses of fine sediment clogged hyporheic zones (surface/groundwater conduits), decreasing the chances of water to infiltrate adjacent stream banks for groundwater recharge.

Most main stem rivers had been narrowed by newly built roads, highways, and dikes which further disrupted floodplain dynamics and increased the rate and intensity in which water flowed out of the system. During floods, peak-flow energy could no longer be dissipated by riparian forests, increasing the discharge rate of water and nutrients from the system. The loss of riparian trees also reduced the possibility of large woody debris recruitment, further affecting in-stream dynamics.

While periodic floods prior to the Euro-American arrival had always had an influence on riparian forests, the scale and magnitude of human-caused disturbance leading up to the 1955 and 1964 floods changed riparian forest composition dramatically.(7) Unrestricted logging had removed most old-growth conifers from stream banks. The floods of 1955 and 1964 further transformed many riparian zones from conifer dominated—to deciduous/hardwood dominated forests.(8)

Deciduous hard woods use (evapotranspire) significantly more water than coniferous trees and can have a more direct impact on stream flows than the surrounding catchment.(6) Nonetheless, early successional deciduous trees such as alder, willow, and cottonwood serve an important function in repairing damaged watersheds.

The Plough and the Sponge

“We believe in going to the bottom of things,—and therefore in deep plowing and enough of it.—Subsoil is the better.” From a “Farmer’s Creed”

Humboldt Times, 1854

Farming and ranching took hold on the lower floodplains where deep soils rich in carbon and minerals had accumulated for thousands of years. Diverse perennial systems (riparian forests and wetlands) would be changed into simplified annual food-based crops or grazing lands.

With farming, the use of ploughs and tractors inverted the soils, altering the soil ecology, as well as oxidizing carbon (humus)—sending stored carbon into the atmosphere. The earth, left exposed from tilling, was lost to erosion in the winter months, and the fine particles of bare soil set free by heavy rains clogged soil pores, reducing infiltration and percolation. The sponge of the lowlands would begin to shrink from the annual ritual of tillage. The overstocking of livestock on the lush lowlands would also contribute to soil compaction, erosion, and the introduction of invasive weeds and grasses.

Urbanization: Paving over the Sponge

Expanses of wetlands and estuaries were drained, diked, altered and rerouted. Large areas of the lowlands would be settled, becoming towns and cities. Urbanization and development would continue to cover vast landscapes with impervious surfaces that no longer could absorb water. The sponge was simply paved over, and the dominant paradigm of development and design influenced by hydrologic illiteracy became the common practice of developers and city/state planners.

The Legacy Continues

As the forest and meadowlands recover, legacy impacts still remain. Beneath the canopy of dense recovering forests lie inactive skid and haul roads continuing to alter hill slope hydrology. These legacy roads still intercept and “daylight” subsurface water from cut hill slopes—racing water out of the system. Gullies formed decades ago, continue to decrease the water table by draining adjacent groundwater to their deep, incised channels. In this manner, water can be rushed out of a watershed at velocities 10 to 1,000,000 times faster than natural processes.(3) Roads are also subject to this phenomenon. Thus, water that would have remained subsurface in deeper soil layers and released slowly, providing stream flows over longer durations—is quickly lost to the ocean.

As North Coast forests continue to regenerate, stream flows have begun to degenerate. Recovering forests composed of dense stands of even-aged trees, are now using much of the available groundwater that exists.(1,2,3) Young stands can use up to three times as much water as old growth forests.(1) The crowded structure of young forests also intercept much of the precipitation that falls, which is then lost to evaporation.

Suppression of Fire

Frequent low-intensity fires and occasional stand-replacing, high-intensity fires, were a “keystone process” that had shaped and influenced North Coast landscapes for millennia prior to Euro-American arrival. The Native peoples were well aware of the benefits of fire and used it as a tool to increase the productivity and resiliency of ecosystems. Beginning in the early 1900’s, the suppression of fire was imposed on the North Coast with a military-like zeal that still continues to this day. Inhibiting this natural process has had inadvertent consequences on the health and resilience of North Coast ecosystems. With the long-term suppression of fire came: the simplification of the landscape, the loss of biodiversity, higher transpiration rates from the now dense undergrowth, and the increase of catastrophic fires.

Douglas-fir seedlings that had historically been kept in check by periodic fires slowly began to invade meadows and the under-stories of deciduous oak woodlands; fuel-loads increased. Areas that had been severely logged became choked with even-aged young Douglas-fir and redwood.

Never before in history have entire forest ecosystems been consumed on such a scale, and fire suppressed for such long durations. The dynamic composition and complexity of the ancient forest ecosystem has been transformed and simplified into a cluttered mass of trees now suspended in secondary succession. When fire does return, the entire recovering system overburdened with fuel loads is often destroyed—and the ecological reset button pushed—once again.

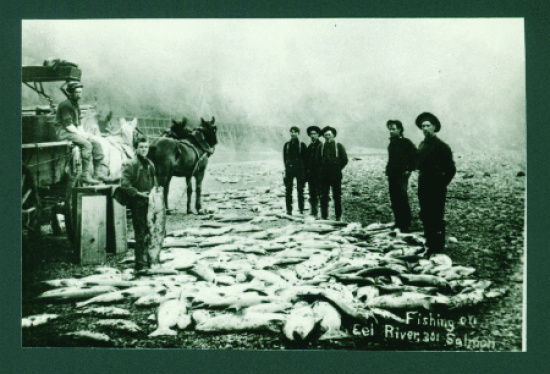

| The impacts of logging and overfishing would eventually diminish the supply of marine nutrients being delivered to interior watersheds. |

| Photo: courtesy Humboldt County Historical Society |

The new settlers wasted no time in their quest to exterminate predators that posed a threat: Grizzly and Black Bears, Mountain Lions, Coyotes, and Badger were trapped, shot, and poisoned. Beavers were hunted almost to extinction, and with the loss of their engineered dams, came impacts to the water table and stream flows. Elk, deer and waterfowl were over-hunted.

Overfishing, as well as rapacious logging, and two catastrophic floods, virtually cut off the annual cycles of marine fertility being delivered by salmon returning to their watersheds of origin. This upstream migration of nutrients had nourished North Coast ecosystems since the last Ice Age. Without the abundant returns of salmon, the health of North Coast watersheds were further degraded and the chance for recovery lessened.

Gold Rush to Green Rush

“Much of what there is to gain from the history of this area is, I’m afraid, a knowledge of the mistakes which should not be repeated.”

Ray Raphael

After more than a century of logging, virtually every watershed on the North Coast had experienced the loss of 90% of its old-growth trees. In economic terms, the new inhabitants of this region were deeply engaged in the process of “deficit spending.” With the forests over-harvested, fisheries plundered, farmlands plowed, and grasslands grazed to bare soil, what were the people of the North Coast to do?

At the tail end of the logging boom, logged-over land and large ranches began to be subdivided and sold. During this period, a new flush of settlers arrived in what was to be called the “back-to-the-land movement.” Many of these people came with the intention to heal the damaged landscape and to heal themselves, seeking a new way of life. Arriving as foreigners, many of them from urban environments, they had much to learn.

The beginnings of the restoration movement were pioneered at this time in response to the declining fisheries and damaged watersheds. Close to the same time, some back-to-the-landers began experimenting (pioneering) the start of the North Coast’s first cannabis culture. What started out as a small trade, became a full-blown black market industry by the 1980’s. The interior watersheds of the North Coast would experience a new “boom”—the Green Rush.

Fast forward to 2012, and we now find ourselves telling many of the same stories of the past. A culture now dependent on an export-based economy (cannabis), subjected to the uncertainties of distant market forces. Like the Gold Rush days of the past, rampant speculation and the influx of new faces seeking short-term profits, has sparked another attack on the still healing landscape. Details on the environmental impacts of the “Green Rush” can be found at: www./treesfoundation.org/publications/article-476, as well as: www.treesfoundation.org/publications/article-486

Severing of the Land/Human Connection

Of all of the damage that was inflicted on the North Coast, perhaps the most profound impact was the forced displacement and attempted extermination of the Native North Coast peoples. With the virtual extinction of some tribes, came the shattering of thousands of years of embedded knowledge on how to persist here. This traditional ecological knowledge contains the oral link to the purpose and skill of maintaining the health and resilience of North Coast landscapes. The loss of this land/human connection has had disastrous effects on our ecosystems and our collective well being.

We will learn in the next article (Part 3), how the use of indigenous wisdom, system-based restoration, ecological design principles, and re-creating localized cultures/economies of place on the North Coast, will help restore both the living sponge and ourselves. (Part 1 can be found at www.treesfoundation.org/publications/article-488)

Kyle Keegan has lived with his family in the Salmon Creek watershed for the past 15 years and has been actively involved in restoration, environmental education, and local issues pertaining to land stewardship. Kyle can be reached at owlsperch@asis.com

Sources:

(1)Barbara J. Bond, Fred C. Meinzer, “How Trees Influence the Hydrologic Cycle in Forest Ecosystems”, 2007

(2)David A. Perry, Forest Ecosystems, John Hopkins U. Press, 2715 N. Charles St, B. Maryland.,pp 453-456

(3)Leonard (Brad) Job, “Engineered Groundwater Recharge as Mitigation for Reduced Summer Low-Flows in the Upper Mattole Watershed”, BLM, Arcata, CA

(4)Nameth Marcy, “Soil as a Superorganism”, Acres USA, June 2010

(5)Ray Raphael/Freeman House, Two Peoples One Place, Humboldt County Historical Society, 2007

(6) R.Dan Moore,S.M Wondzell, “Physical Hydrology and the Effects of Forest Harvesting in the PAC-NW:A Review” Journal of the American Water Resources Board, 2005

(7)Stacy Urner, Maryanne Madej, “Changes in Riparian Composition and Density Following Timber Harvest and Floods along Redwood Creek CA”, Redwood Field Station, 1997

(8)Thomas E Lisle, “Channel-Dynamic Control of the Establishment of Riparian Trees After Large Floods in NW CA”,USDA Forest Service, 1986

(9) “CA Coastal Prairies” http://www.sonoma.edu/preserves/prairie/index.shtml

(10)”Glomalin: Hiding place for a Third of the World’s stored carbon” http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/ar/archive/sep02/soil0902.htm

More Articles…

CLICK TO MANAGE