Brandie Wilson with Rebel the dog at the Humboldt Area Center for Harm Reduction. | Photo by Ryan Burns.

Brandie Wilson is an intense person, and after five years at the helm of Humboldt County’s most controversial and polarizing nonprofit she had reached the end of her fucking rope.

That’s how she phrased it, and if you’re averse to f-bombs, well, don’t expect her to apologize.

This past Friday was Wilson’s last day as executive director of the Humboldt Area Center for Harm Reduction (HACHR), the syringe-exchange program she founded in 2014, and in a recent sit-down interview at the nonprofit’s Eureka offices she said this departure was always part of her plan.

Why?

“Because I know who the fuck I am,” she said. “I know that I’m a creative person and I also know that I struggle with bouts of mental health issues. I have an understanding of my capacity.”

Plus, she said, “best practices” show that the people who start nonprofits tend to get possessive of the organizations they’ve built, and their overprotectiveness can stifle growth. So it’s always been her plan to leave HACHR.

She reiterated that a couple times, that her departure was planned, because she wanted to make sure that HACHR’s most fervent critics — the people who’ve made personal attacks and death threats on social media, who exaggerate and lie about the program, who harassed her in public and posted her home address online, and whomever it was that keyed her car — she doesn’t want any of them thinking that their approach worked, that they ran her off.

On a recent episode of the HACHR podcast, which is called #factsmatter, Wilson even thanked the people who, as she put it, have given the organization hell.

“You showed us where our weak spots are,” she said. “You showed us how to always be one [step] ahead of the strategy. … Thank you for making me the powerful advocate that I am, for putting me through this amazing journey the past five years.”

That journey began with a pleading email she sent to various national drug policy organizations in 2014, asking for advice.

“I was freaked out because someone I knew died; then more people died. In a short period of time so many fuckin’ people had died,” she said, referring to drug-related deaths. “And then I started looking into why everyone’s fuckin’ dying here, because it just hadn’t been in my purview. And when I started looking at data I was like, ‘What the fuck?’ It just blew me away.”

Specifically she looked at the 2011 Rural Community Vital Signs report produced by the California Center for Rural Policy (pdf here). Among the findings was that Humboldt County, at the time, had the highest drug-induced death rate in California, and it was rising.

Wilson, who holds a degree in sociology from Humboldt State University, saw a need to address the issue systematically, and her email seeking advice prompted a response from Amanda Reiman, then the California manager for the Drug Policy Alliance. Reiman urged Wilson to apply for one of the agency’s annual “Promoting Policy Change” grants. In order to be eligible Wilson had to form a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, and before long, HACHR was born.

For Wilson, the back end of that acronym — the part that stands for “harm reduction” — represents a philosophy she came to through a difficult and circuitous path. Raised in a rural farming community in the Central Valley, she attended kindergarten through eighth grade at a Christian school where strict moralizing was ever-present and “science wasn’t a thing,” she said. “It was religion and memory and chapel.”

A nonbeliever who also happened to be attracted to girls, “I spent most of my life being told that something’s wrong with me, morally,” Wilson said.

She battled substance use and mental health issues as a teenager, got married at 18, quickly divorced, and after being sexually assaulted she entered a 10-year stretch of chaotic drug use. That period of her life found her homeless on the streets of Reno, incarcerated back in the Central Valley, in and out of drug court and, more than once, on the run from the law.

None of it — the punishment, the moralizing, the trauma — worked to curb her drug use. “And then I got an education,” she said. “And an education worked.”

Sociology gave Wilson a lens through which to view America’s drug epidemic and the failed war against it. And Reiman, with the Drug Policy Alliance, introduced her to the concept of harm reduction, a public health approach to drug treatment that encourages positive change without judgment or punishment.

“I had no clue about harm reduction until then, which is insane to me,” Wilson said.

In line with this approach, the California Department of Public Health encourages syringe-exchange programs such as HACHR to adopt a needs-based distribution method, which means giving out as many free, sterile needles as people request. The idea is to prevent the spread of communicable diseases such as HIV and Hepatitis C while making other resources available to people who inject drugs.

“Public health research has consistently found that restrictive models [such as requiring a one-to-one exchange ratio] increase syringe re-use and sharing among program participants,” the state notes.

When Wilson launched HACHR, she did so with this needs-based distribution approach, and public resistance was intense.

“Making space for people who use drugs in this community, in this way, was really, really hard,” Wilson said. It was an uphill battle just getting people “to acknowledge that we’re humans and we have rights and those rights aren’t negotiable.”

Many — not just here in Humboldt County — are inherently offended at the idea of handing out free needles so people can inject illegal drugs. It seems to them like enabling or even encouraging drug use. When addiction is viewed as a personal failing, as the sole province of criminals, reprobates and hedonists, the only acceptable responses are shaming and punishment.

Wilson said the United States has taken that approach for the past 50 years. “It’s how we got here,” she said. From Nixon’s declaration of a “war on drugs” through the Reagan era’s “Just say no” mantra and Clinton’s “three strikes” policy, “You can see the progression of the punitive measures of the drug war and how it escalated and got us here,” Wilson said.

HACHR’s approach, in contrast, is based on historical precedent and research about what actually works, Wilson said. As an example she pointed to Portugal, which has seen dramatic drops in overdoses, HIV infection and drug-related crime since 2001, when it became the first country in the world to decriminalize the possession and consumption of all illicit substances.

That’s not to say that one size fits all.

“Originally we did a straight needs-based distribution across the board because that’s what we thought we should do,” Wilson said. “However, we needed to modify that with the understanding that we have a huge homeless population.”

File photo from a 2018 protest, which was accompanied by a counter-protest. | Andrew Goff

By the time HACHR made that modification, needle litter had become the most polarizing political issue in Eureka, along with the organization itself. Protesters took to the streets and to social media, voicing their anger at city council meetings and organizing to “Take Back Eureka” from “all the crime, drugs, solicitors, trash and vandalism.” These social woes, many felt, could be laid squarely at the feet of HACHR.

Wilson wasn’t totally surprised by the criticism.

“I think that at the beginning everyone was new to this,” she said. “The community, leadership, us, we were all new to this. And it’s scary, right? It’s a scary thing. So, I understand. And I understood at first. But what I then began to not understand was, I just didn’t understand how things were allowed to get as far as they did.”

She recalled Eureka City Council meetings where people made comments that felt like personal attacks, where people said HACHR should be eradicated or run out of town, where the raucous crowd cheered and hissed. “People were allowed to do it in person, so why wouldn’t they do it online?” she said.

A handful of the most vociferous critics took things further. Some called HACHR’s funders to complain; others spread misinformation online in an attempt to discredit the organization; and a few confronted and threatened Wilson, both online and in public.

These people represent a small minority, she said. Their numbers pale in comparison to HACHR’s supporters. But the dedicated harassment campaigns took a toll. It’s what dragged her to the end of her rope.

“I don’t leave my fucking house. I don’t go to community events. … It’s fucked up, what’s been allowed to get to this point.”

“It’s been the worst shit I’ve ever dealt with,” she said. “I don’t leave my fucking house. Safeway delivers my fucking groceries. When Uber Eats and DoorDash started I was so fucking excited because I don’t leave my fucking house. I don’t go to community events. I go to CVS because it’s near my house and because in WinCo someone yelled at me to pick up my fucking syringes, and at Safeway people always want to talk to you? It’s fucked up, what’s been allowed to get to this point.”

Later in the interview, after we asked Wilson to address complaints about needle litter and illegal overnight camping on HACHR’s property, she got visibly exasperated.

“These people are so pissed off about a fucking cap or a fucking needle. They don’t fucking care if people are going to fucking die. Fuck them! You don’t fucking deserve to be a part of this community. If that’s how you think and that’s how you feel, go fucking build a community somewhere else. There are a lot of fucking people in this place trying, that fucking value people. And those assholes that want to know about camping, that want to know about litter? Fuck you! Go fucking build housing and it will all be fixed.”

She’d started crying.

“Makes me so fucking upset,” she said. “There’s like seven people who are goddamn assholes who are making it hell for everyone.”

Some critics have seized on the fact that Wilson defines herself, to this day, as a person who uses drugs.

“Because I am a person who uses drugs,” she said. “Whether or not they are prescribed by my doctor; they’re still drugs.” Beyond tobacco and cannabis she didn’t identify which drugs she still uses. On the HACHR podcast she said that while she’s never been an injection drug user, she has had “massive chaotic bouts of drug use.”

She went on to say that she’s been “chaotic-use free” for some time now. Stories about her drug use are just another attempt to discredit her, she said, and in our interview she voiced frustration with those who refuse to accept research data and evidence while spreading beliefs that aren’t grounded in fact.

“The research and science shows that the goal is to meet people where they’re at, and through that you create a connection,” she said. “You treat people like people, and you create a plan according to what that person thinks is most critical in their life, because going from full-blown chaotic use on the street to housed, fully-functional, clean [and] employed is almost never done immediately. Research shows that’s not a thing that happens very often. And when it does, that’s glorious. [But] we need people who understand that struggle. And just because I say I’m a person who uses drugs, why does that negate anything?”

Asked how HACHR defines success, Wilson quoted a phrase (which has since become a hashtag and rallying cry) from Dan Biggs, a drug-treatment pioneer who died last year: “Any positive change.”

“Because every day, if you did a positive change? Great,” she said. “Now we can start from there tomorrow and do another positive change. … That’s real. That is our path. Our path is not so boldly linear as it is creative, but we get there.”

Wilson has seen these changes take place and build on each other until people’s lives have been transformed. She sees former HACHR clients out in the world. Sometimes they stop by to give staff hugs and tell them “thank you,” she said.

HACHR did eventually modify its approach, moving away from a totally needs-based syringe distribution method in recognition of Eureka’s specific issues, including its high concentration of homelessness, poverty and mental health issues.

Jessica Smith, a longtime HACHR volunteer and employee who this week took over Wilson’s position as executive director, explained the methodology.

Now, she said, when people come in for the first time they’re given a list of dos and don’ts, a rundown of what’s expected (including bringing used needles back) and an explanation of how the exchange works.

“We get to meet with our consumers and make relationships with each and every one of them,” Smith said. “So we know who is housed and who isn’t, and who is bringing back their syringes regularly and who isn’t. So we determine what happens based on those relationships.”

If a person who’s homeless comes in and asks for 500 needles, “it’s not safe for them,” Smith said. “They’re going to get stolen, [or] the police are going to stop and arrest them.”

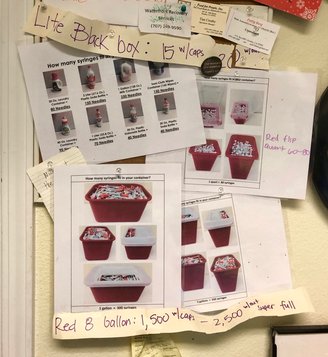

Print-outs on the wall at HACHR.

So the number of needles distributed is based in part on each client’s personal situation and in part on how many needles those clients bring back in. On wall in HACHR’s reception office, tacked-up printouts show images of various containers filled with syringes. These are guidelines from the California Department of Public Health showing how many needles fit into each container.

A one-gallon milk jug holds 250 needles. A two-liter Coke bottle? 150 needles. A big, red two-gallon, FDA-approved sharps container can fit 550. HACHR uses these guidelines to count returned needles.

Many critics have questioned HACHR’s methodology. They suspect staff of overestimating or fudging the numbers to make their exchange rate look better, and they’ve called for HACHR to be more transparent, to publicly disclose their monthly stats, including the number of needles they pick up, their exchange ratio and more.

Wilson said they used to provide some of that information, but it didn’t appease anyone.

“People behaved quite nasty,” she said. “It wasn’t a normal conversation. … It immediately goes into, ‘They’re lying! That junkie Brandie!’ The usual shit. So when people behave badly we’re not going them give them the tools to beat us.”

Last fall HACHR became a state-authorized syringe-exchange program, which means the organization no longer has to report directly to the City of Eureka.

“The state is our authorizing body,” Wilson said, “so they get yearly reports and that’s what they have asked for and that’s what we will do.”

As for the accuracy of needle-counting, Bill Taylor, a retired engineer, spent three days last year testing HACHR’s methods after a Eureka City Councilmember said it sounded like little more than guesswork. Taylor conducted experiments, weighing needles with and without caps, taking measurements and counting each individual one.

“In my mind it verified the technique they’re using,” he told the Outpost. After coming in as a skeptic he wound up volunteering for the organization. He’s done everything from putting stickers on sharps containers to registering people to vote, taking them to doctors’ appointments and picking up donations for a winter clothing drive.

“Hell, I go over there to hang out,” he said.

Wilson acknowledged that needle litter is a legitimate concern, which is why they have their own cleanup crew and pay an employee to go out and pick up needles four or five days a week.

Smith said HACHR now does case management, testing people for Hep C and HIV, offering to make treatment appointments at Open Door, handing out the naloxone, the opioid-overdose-reversal medication, to those who need it. It’s the “warm handoff model,” Smith said.

Wilson said the problems in Humboldt County are a lot more complex than HACHR critics like to think and suggested we need to focus on building housing and addressing mental health.

“Everyone wants to attack people who use drugs, but we have conversations with all these folks,” she said. “We know what’s going on. We know that it’s not just drug use.”

Nor did Wilson or HACHR create the problem. “I became the symbol of 50 years of bad drug policy,” she said. “And that’s stupid.”

Not everyone felt that way, of course. During her tenure Wilson was also lauded by the New York Times, among other media outlets, and last year the American Red Cross bestowed her with a Healthcare Hero award in recognition of her “exemplary service to the community.”

Wilson said that while Humboldt County’s social issues often seem intractable, the people who’ve supported groups such as HACHR and Betty Chinn and John Shelter outnumber those trying to tear them down.

“This community is full of so many amazing and supportive groups of people, and there’s a lot of people doing great work to get some of these systemic failures fixed,” she said. Specifically she mentioned Affordable Homeless Housing Alternatives (AHHA), Open Door Community Health Centers, St. Joseph Hospital and the Humboldt Patient Resource Center.

Wilson has now moved out of Humboldt County, her home for the past 15 years. She said future plans include some national consulting work, helping to develop other programs with a similar mission to HACHR.

“Basically I’m moving to a bigger stage of harm-reduction work,” she said. And the organization she founded lives on.

CLICK TO MANAGE