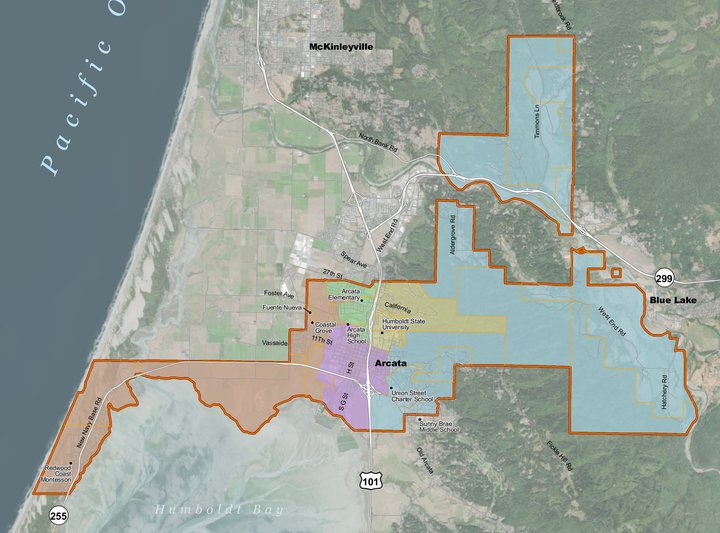

The new districts were drawn by consulting firm Planwest Partners. Click for a larger PDF version.

###

There are three seats up for election on the Arcata School District

board of trustees, but two people are running … and they’re

running for the same seat. Because of the district’s transition to

trustee-area voting — changed for the sake of equity, and to avoid a

lawsuit — only a fifth of ASD’s constituents are eligible to vote

on the one contested seat.

These unique circumstances are the result of a settlement agreement related to the California Voting Rights Act of 2001, which prohibits at-large elections — elections in which trustees represent all voters within school district boundaries — if they impair the ability of minority voters to influence an election. The solution is implementing trustee-area voting, in which trustees represent only voters who live in the same district.

Transferring to district elections has successfully diversified representation on many school boards throughout California. Because specific neighborhoods sometimes have higher populations of protected class voters, trustee area voting ensures that their votes are not diluted.

The Arcata School District made the switch to district elections, leaders say, because it believes in the Voting Rights Act, and because it believes that equity in the district is an important goal. But it also did so in the face of a threat of a lawsuit from an out-of-town attorney, backed by a somewhat obscure interest group, which collected a settlement fee from the district before backing down.

As to whether the district’s new election system will actually empower more people to participate in school governance — that’s still very much an open question.

###

One year ago, ASD Superintendent Luke Biesecker received an email from an attorney, H. Frederick Seigenfeld, who wrote on behalf of Arcata resident Marquita Simms. Simms worried that at-large elections impaired the chances of protected classes to gain a seat on the board, and Seigenfeld cited that the district had not complied with the CVRA and indicated an intention to sue.

A valid CVRA complaint must come from someone living within district boundaries. Simms was the face of the operation, but the muscle came from a third party way down in Santa Barbara, at a nonprofit called the California Voting Rights Project. Alan Ebenstein, the organization’s founder and president, is the person who initially told Simms about racially polarized voting and the CVRA. At the time, the two were distant acquaintances. Simms sings for the same gospel choir that Ebenstein’s brother plays piano for, Simms told the Outpost over the phone.

Ebenstein “brought to my attention that a lot of the minority students were not being represented in the schools here in this particular area, and that there was an easier way to do that,” said Simms, who does not have any kids in the district.

“And so, I was like, ‘okay, explain it to me,’ and they did and I said, ‘okay, well, I understand that,’” Simms said. “Neighborhood representation is really good, you know, because the neighborhoods vary, you know, the people vary in the community. So yeah, we want adequate representation for everyone, and pretty much that was just the jist of it. It wasn’t anything more than that. It was just, you know, yeah, I agree, is pretty much what it was. I agree that we need representation as well, as minorities.”

Simms didn’t mention Seigenfeld, and said it was Ebenstein who facilitated everything once she agreed with the concerns. “He did most of the work as far as that went, because I did let him know that I was not really into politics,” said Simms, who was hesitant to speak to the Outpost. “I agreed with the concern, and so he pretty much handled everything for me.”

Ebenstein, who is an economics professor at UC Santa Barbara and was a Republican candidate for California State Assembly in 1992, spoke to the Outpost over the phone recently. He has been involved in efforts to implement trustee area voting for over 20 different entities, including city councils and school boards. “People who are local neighborhood leaders can become elected to city councils and school boards rather than people who are backed by political interests, perhaps representing the larger area,” Ebenstein said. “And that’s a good thing, because elected bodies should represent the whole community.” Additionally, he claimed that trustee areas typically result in larger candidate pools and higher voter turnout. His organization, the California Voting Rights Project, noted that “no member of a protected class has sought election to the Arcata School District Board of Education since 2001,” according to a report that Ebenstein shared with the Outpost. It is unclear how the organization determined that the candidates cited were not members of protected classes, and it appears as though the claim was based on surname alone.

Ebenstein contacted Seigenfeld, an attorney also from Santa Barbara who has sent letters regarding the CVRA before. Around the time Seigenfeld wrote to ASD, he sent the same letter to the City of Marina, but failed to find a voter who was a Marina citizen and had to try again a couple months later.

ASD’s response to the letter was swift. “There was no lawsuit,” Biesecker told the Outpost during a phone call, “but we did reach a settlement agreement to resolve their concerns and reach an agreement on a reimbursement for costs incurred for the work to produce and support the notice of concern.” Simms was eligible to seek those fees because under the CVRA, the aggrieved voter shouldn’t suffer financial consequences of making a complaint. The district paid $21,000 and voluntarily began the process to transition to trustee area voting.

The settlement agreement was the most financially prudent action to take, Biesecker said. In recent years, lawsuits against cities and school districts that use at-large voting have swept through California, and prosecutors almost always win these cases. In fact, when Biesecker received the complaint, no district had ever successfully argued a defense. In some cases, districts have had to pay upwards of a million dollars after challenging the law.

“I’m not saying this would have been that expensive but there was, you know, that’s a huge amount for a small district like us,” Biesecker said. “That would have been crippling. I don’t know how we would have continued to operate or how that would have worked.”

###

Through a series of public meetings, the ASD board approved a transition to trustee-area voting for the November 2020 election and hired a contractor to make a map of new district areas, which was meticulously constructed to empower minority classes. Usually, transitioning to trustee-area voting requires approval by a district-wide election, but in May ASD got a waiver from the California State Board of Education to transition immediately. The total cost of the process, including the settlement, was $30,000.

The intention is to increase representation on the board, a goal that Biesecker has hopes for, but with a note of reservation — ASD covers a small population that is predominantly white, and drawing a map that encompassed minority classes so that the area-voting system would serve its purpose was a stretch. There are not significant blocks of protected class voters in one neighborhood versus another, Biesecker said. “I’m not sure how much [it’s] really going to benefit us, but we’re going to find out.”

Ebenstein admitted that Arcata is one of the smaller places where he’s advocated for trustee-area voting, but said it’s “large enough, and there are enough students for it to be a valid concern.” He disagreed with Biesecker regarding Arcata’s composition. “I think that if there are distinct neighborhoods in a jurisdiction as there are in Arcata, then it makes sense to have district elections,” he said, adding that the enrollment at ASD has become “considerably more diverse in recent years than it historically was.” Biesecker confirmed that ASD is gradually becoming a more diverse school district.

Data from the California Voting Rights Project write-up that Ebenstein shared with the Outpost show that he was referring to the total enrollment of the district, including its charter schools. The data in this report, which were collected from the California State Department of Education, cite a total enrollment of 1,129 students in the 2018-2019 school year, with 67.7 percent of that population identifying as white. However, ASD’s four charter schools — Coastal Grove, Redwood Coast Montessori, Union Street and Fuente Nueva — have independent governance. ASD’s school board represents only 500 students and two schools — Arcata Elementary and Sunny Brae Middle.

Additionally, the write-up cites census data to show that ASD enrollment is reflective of the larger community, but the data contradicts what was used by Planwest Partners, the mapping service that ASD hired. Because ASD does not cover the entire population of Arcata, Planwest Partners accounted for 5,000 fewer people than the California Voting Rights Project did to conduct an analysis of fair representation on the ASD board. Based on data comparison, a large number of the 5,000 people living outside of the district are protected classes. These people were included in the California Voting Rights Project’s justification for implementing trustee area voting, however, they are not eligible to run or vote for ASD seats.

According to Planwest Partners, the total population within the district is 14,599, and they aimed to minimize population difference between the five trustee areas with an average population of 2,920 in each district. Within district boundaries, there are 310 people who identify as Black, 321 who identify as American Indian, 367 who identify as Asian and 1,700 who identify as Hispanic. Planwest Partners didn’t have a “multi/other” ethnic population taken into account for the map making process, but the California Voting Rights Project did consider this group in their report with a total population of 807 in the city of Arcata.

Planwest Partners reported at a January 2020 meeting that it was difficult to keep protected classes in one trustee area.

The company presented three maps to the ASD board, which ultimately selected the map with the best protected class-to-population ratio. This map empowered voters in areas 3 and 5, with a population of 81 Black and 84 American Indian voters in Area 3, and a population of 134 Asian and 494 Hispanic voters in Area 5 — each out of a total of nearly 3,000 residents.

No one filed to run for areas 3 and 5, which cover Arcata Elementary and Humboldt State, respectively.

###

ASD welcomes the potential for more balanced representation on its board. “Equity is really important to the board of trustees and the district. It’s a priority for us,” Biesecker said. At the same time, they fear that seats might not fill.

When Seigenfeld sent the letter on behalf of Simms, there was an open seat on ASD’s board, which the district was having a hard time filling. The district invited Simms to apply for the open seat, but she declined. So when the board unanimously agreed to transition to area voting, the vote was paired with concerns that the change would leave some seats unoccupied on a board that faced difficulty filling vacancies to begin with. Struggling to maintain a quorum could affect district operations, Biesecker said.

Because they live in the wrong districts, two trustees who might have run as incumbents — John Schmidt and Prairie Moore — now don’t have the option to. Schmidt confirmed with the Outpost that he would have rerun had it been an option, and Moore didn’t respond by publication.

Meanwhile, Biesecker thinks that “there were other people interested maybe in running this time around, but they weren’t in the trustee area that was up for election.”

The two vacant seats will be filled by appointment in lieu of election. The district sent out a letter seeking applicants for appointment, and Biesecker confirmed that they’ve received two applications from Area 3 and one from Area 5. Applicants will be interviewed and selected by the current board.

Ebenstein said that COVID-19 is likely to blame for the lack of interest in those seats. “I believe that in the future, that wouldn’t be the case,” he said.

Ebenstein, who identifies as pro-education, once attempted to establish a ballot measure to end union representation of California State employees through a different nonprofit he founded, called the California Center for Public Policy. When he was campaigning for signatures, Ebenstein told The Sacramento Bee that “unions have too much influence and the pay and perks their members receive are leeching money from government services, like education.” He’s pro-education funding, but for a small district like ASD, $21,000 toward a settlement was a significant hit to their budget.

“We like to feel like we run a pretty tight ship, you know, that we’re using government funds — public funds — very thoughtfully,” Biesecker said. “Every dollar we spend, we want to make sure that it’s going to support student learning and education. And so we can do a lot with, you know, $20,000 in additional staffing [and] programs for students.”

So why go through a lawyer at all? Why not send a letter — on behalf of a citizen — directly from the California Voting Rights Project itself, in order to save the district money while instigating a transition to trustee-area voting?

“That’s a good question,” admitted Eberstein, who claimed his organization has facilitated the process without lawyers before. “In the case of the Arcata School District, I think, because it was the first in the county, it seemed like maybe it was better to be more proactive,” he said, adding that the settlement agreement at ASD was “a considerable reduction from the the maximum amount that can be charged,” which is $30,000 according to the CVRA. “We appreciate that these are, you know, expenses, and at the same time, the issues of voting are very important.”

Ebenstein confirmed that although the California Voting Rights Project does not have “specific plans” for other Humboldt school districts at this time, he might pursue implementing district elections elsewhere in the county in the future.

Ebenstein couldn’t promise that he wouldn’t use a lawyer should he return to Humboldt.

It is unclear how much of the settlement money went towards the California Voting Rights Project. Ebenstein did not directly answer the question and said that it varies based on the size of the district and the amount of data that needs to be gathered. “Sometimes we’ve, you know, taken a loss to implement district elections somewhere,” he said.

The California Voting Rights Project is not a registered 501(c)3. The organization doesn’t currently have a website; Ebenstein said it is being redone.

If the trustee voting system doesn’t work, Biesecker said that the district might discuss transitioning back to at-large elections in the future.

Since the district began the transition, an appellate court ruled that dilution of protected classes must be evident in order to require a switch to trustee area voting as the result of a lawsuit. This precedent might apply to ASD and protect the district if they were to transition back to at-large elections.

For now, the Area 4 seat is contested, with incumbent Joe McKinzie and challenger Brian Hudgens both residing in that district. In terms of ASD, only those living in Area 4, which includes a large chunk of southern Arcata and downtown, will have something to mark on their ballot.

CLICK TO MANAGE