Why Aren’t There Buses to Bayside, or on Sundays?

Dezmond Remington / Wednesday, Dec. 31, 2025 @ 7:32 a.m. / Transportation

An HTA bus.

There are around nine miles between Arcata and Eureka, and there’s a lot of highway beyond both. For people without a car or with disabilities, covering the distances between Humboldt’s far-flung towns can be an insurmountable task without public transportation.

At recent public meetings around the county, the floor was open to members of the public who had “unmet transit needs” to share with local policymakers, who then passed them on to the Humboldt County Association of Governments (HCAOG). None of the Humboldt Transit Authority’s (HTA) buses run on Sundays and none of the Arcata & Mad River Transit System’s make it out to Bayside, two inconveniences that affected many of the commenters at Arcata’s unmet needs hearing on Nov. 19.

So why don’t they? — a simple question with several answers.

HCAOG’s associate regional planner Stephen Luther told the Outpost in an interview that they’d looked into Bayside service after many requests from community members, digging into census tract and transportation data. According to the 2020 census, there are roughly 1,800 residents in Bayside; six of them took the bus to work. HCAOG concluded that it wasn’t feasible because its population density isn’t high enough to justify the cost. Stops on the Red and Orange routes near the Murphy’s in Sunny Brae average around 30 people daily getting on and off there; Luther estimated adding stops deeper into Bayside would increase that by single digits.

“In terms of regular commuters that would be commuting into Arcata,” Luther said, “It was pretty low.”

According to last year’s unmet needs summary, buses used to run to Bayside “some time ago,” but that ended because so few people used it. HCAOG’s staff asked HTA if they could extend the Red line down Old Arcata Road to Bayside Corners; HTA said it’d add 8 minutes to the loop and couldn’t be done. In 2016, HTA added bus service down Old Arcata Road. Within two years, it was discontinued for the same reason.

Buses may one day run again to Bayside when the Roger’s Garage low-income housing project is constructed, according to the summary. But for the time being, it’s simply too expensive.

The same goes for Sunday bus routes. The big number: it’d cost about $600,000 annually to fund the route on Highway 101 called the Redwood Transit System (RTS), $200,000 from operating costs, like maintenance and fuel, and the rest from the five new people HTA would have to hire to keep operations running another day of the week.

HTA used to run buses on Sundays, but declining use during the pandemic killed it.

An estimated 237 people would use the service every Sunday. With the standard $2 rider fare, that means it’d run HTA about $15 every time someone rode the bus (what HTA calls their “operating subsidy”). It’d put that program deep in the red.

HTA’s deputy general manager Katie Collender told the Outpost they’re looking for an operating subsidy closer to $3 a rider.

Consultants for HTA also recommended that if RTS Sunday service started, the intra-city bus routes should also run on Sunday. Funding that would be another huge expense HTA can’t meet: $95,000 for Eureka and another $67,000 for Arcata (even when only running the Orange route).

“Bottom line and big picture, we’d love to have Sunday service,” Luther said. “We recognize it as an unmet need that does need to be filled. There are a lot of people that comment on this process that need the bus to get to work on Sundays. Who maybe work later in the evenings at a restaurant and rely on the bus to get home, but it doesn’t run late enough in the night. So there are many of these transit needs that we hear, year after year, that are just super challenging to implement.”

He said there was a “tension” between bus coverage and bus frequency; it’s expensive to add both at the same time.

“You really can’t have everything,” Luther continued a few minutes later. “We have a limited amount of funding. HTA does everything they can to get as many dollars as they can, to make it stretch as far as they can … If HTA can start a service and operate it, they’re going to.”

BOOKED

Today: 7 felonies, 9 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

Us101 S / 12th St Ofr (HM office): Traffic Hazard

Us101 / Indianola Cutoff (HM office): Traffic Hazard

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: High Surf Advisory Issued for the North Coast

RHBB: Protest Planned at Humboldt County Courthouse This Afternoon Over ICE Shooting in Minneapolis

County of Humboldt Meetings: Mayors’ City Selection Committee Meeting Agenda

RHBB: Motorcycle and Car Collide Near Fortuna Main Street Onramp

California’s Budget Outlook Is Grim. Here’s What You Need to Know

Yue Stella Yu / Wednesday, Dec. 31, 2025 @ 7 a.m. / Sacramento

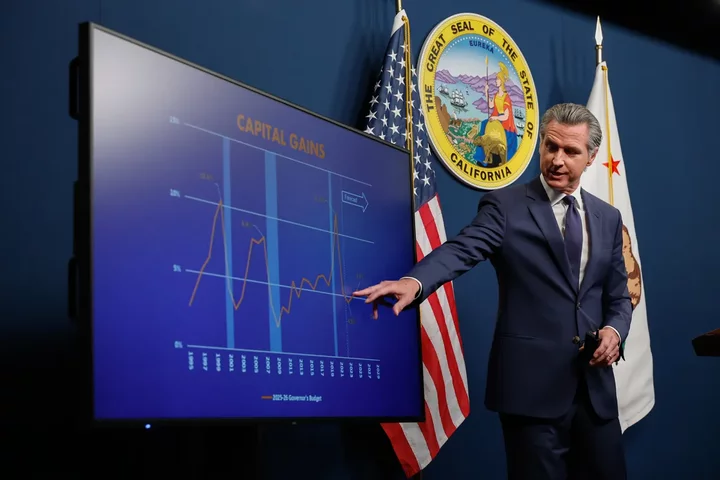

Gov. Gavin Newsom releases his revised 2025-26 budget proposal in Sacramento on May 14, 2025. Photo by Fred Greaves for CalMatters

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

Gov. Gavin Newsom opened this year with a rosy forecast: Buoyed by $17 billion more in revenue than previously planned, the state would have a modest surplus of $363 million for fiscal year 2025-26, he told reporters in January.

But life turns on a dime.

The January wildfires that ripped through Los Angeles forced the state to spend billions in disaster aid and delay tax filings for LA residents. The cost of Medi-Cal, the state-run health insurance program for low-income residents, ballooned to $6 billion more than anticipated. President Donald Trump’s on-again-off-again tariff policies rocked the stock market, which California heavily relies on for tax revenue. And the state lodged a flurry of lawsuits against the Trump administration over its threat to withhold federal funding for food assistance, disaster recovery and other grants.

By May, Newsom no longer predicted a modest surplus, but a $12 billion deficit.

To plug the hole, Newsom initially proposed drastic cuts to Medi-Cal. But the final budget he negotiated with state lawmakers depended largely on internal borrowing, dipping into the state’s reserves and freezing Medi-Cal enrollment for undocumented immigrants to avoid deep cuts to other social services.

While Democratic leaders largely blamed the Trump administration for California’s budget problem, the volatility of state revenues is not new. California highly depends on taxing the income and capital gains of high earners, whose fortune is often at the mercy of the stock market. In 2022, the state saw a nearly $100 billion surplus, followed by a projected $56 billion deficit over the next two years.

2026 outlook

The deficit is projected to reach nearly $18 billion next year, mostly because the state is expected to spend so much money that it would offset, if not eclipse, the strong tax revenues driven by an AI boom, said the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office in its fiscal outlook last month.

If the estimate holds, it’ll be the fourth year in a row in Newsom’s tenure that California faces a deficit despite revenue growth.

Worse yet, the structural deficit could reach $35 billion annually by fiscal year 2027-28, the LAO said.

California is facing $6 billion in extra spending next year, including at least $1.3 billion because the state must now pay more to cover Medi-Cal benefits under Trump’s budget bill. The state also stands to lose more housing and homelessness funding from the federal government.

How can legislators fix it? The options are stretching thin, as the state already took one-time measures to balance the books. The LAO notes that solving an ongoing structural budget problem requires either finding more sustainable revenue streams, or making serious cuts, or both.

Scared of Artificial Intelligence? New Law Forces Makers to Disclose Disaster Plans

Khari Johnson / Wednesday, Dec. 31, 2025 @ 7 a.m. / Sacramento

A new California law requires tech companies to disclose how they manage catastrophic risks from artificial intelligence systems. The Dreamforce conference hosted by Salesforce in San Francisco on Sept. 18, 2024. Photo by Florence Middleton for CalMatters

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

Tech companies that create large, advanced artificial intelligence models will soon have to share more information about how the models can impact society and give their employees ways to warn the rest of us if things go wrong.

Starting January 1, a law signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom gives whistleblower protections to employees at companies like Google and OpenAI whose work involves assessing the risk of critical safety incidents. It also requires large AI model developers to publish frameworks on their websites that include how the company responds to critical safety incidents and assesses and manages catastrophic risk. Fines for violating the frameworks can reach $1 million per violation. Under the law, companies must report critical safety incidents to the state within 15 days, or within 24 hours if they believe a risk poses an imminent threat of death or injury.

The law began as Senate Bill 53, authored by state Sen. Scott Wiener, a Democrat from San Francisco, to address catastrophic risk posed by advanced AI models, which are sometimes called frontier models. The law defines catastrophic risk as an instance where the tech can kill more than 50 people through a cyber attack or hurt people with a chemical, biological, radioactive, or nuclear weapon, or an instance where AI use results in more than $1 billion in theft or damage. It addresses the risks in the context of an operator losing control of an AI system, for example because the AI deceived them or took independent action, situations that are largely considered hypothetical.

The law increases the information that AI makers must share with the public, including in a transparency report that must include the intended uses of a model, restrictions or conditions of using a model, how a company assesses and addresses catastrophic risk, and whether those efforts were reviewed by an independent third party.

The law will bring much-needed disclosure to the AI industry, said Rishi Bommasani, part of a Stanford University group that tracks transparency around AI. Only three of 13 companies his group recently studied regularly carry out incident reports and transparency scores his group issues to such companies fell on average over the last year, according to a newly issued report.

Bommasami is also a lead author of a report ordered by Gov. Gavin Newsom that heavily influenced SB 53 and calls transparency a key to public trust in AI. He thinks the effectiveness of SB 53 depends heavily on the government agencies tasked with enforcing it and the resources they are allocated to do so.

“You can write whatever law in theory, but the practical impact of it is heavily shaped by how you implement it, how you enforce it, and how the company is engaged with it.”

The law was influential even before it went into effect. The governor of New York, Kathy Hochul, credited it as the basis for the AI transparency and safety law she signed Dec. 19. The similarity will grow, City & State New York reported, as the law will be “substantially rewritten next year largely to align with California’s language.”

Limitations and implementation

The new law falls short no matter how well it is enforced, critics say. It does not include in its definition of catastrophic risk issues like the impact of AI systems on the environment, their ability to spread disinformation, or their potential to perpetuate historical systems of oppression like sexism or racism. The law also does not apply to AI systems used by governments to profile people or assign them scores that can lead to a denial of government services or fraud accusations, and only targets companies that make $500 million in annual revenue.

Its transparency measures also stop short of full public visibility. In addition to providing the transparency reports, AI developers must also send incident reports to the Office of Emergency Services when things go wrong. Members of the public can also contact that office to report catastrophic risk incidents.

But the contents of incident reports submitted to OES by companies or their employees cannot be provided to the public via records requests and will be shared instead with members of the California Legislature and Newsom. Even then, they may be redacted to hide information that companies characterize as trade secrets, a common way companies prevent sharing information about their AI models.

Bommasami hopes additional transparency will be provided by Assembly Bill 2013, a bill that became law in 2024 and also takes effect Jan. 1. It requires companies to disclose additional details about the data they use to train AI models.

Some elements of SB 53 don’t kick in until next year. Starting in 2027, the Office of Emergency Services will produce a report about critical safety incidents the agency receives from the public and large frontier model makers. That report may give more clarity into the extent to which AI can mount attacks on infrastructure or models act without human direction, but the report will be anonymized so which AI models pose this threat won’t be known to the public.

Eureka Police Officer Placed on Paid Leave After Christmas Eve Arrest for Alleged Drunk Driving

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, Dec. 30, 2025 @ 2:16 p.m. / Crime

Eureka Police Chief Brian Stephens (left) swears in James Whitchurch upon the latter’s graduation from the College of the Redwoods Police Academy in June. | Screenshot from EPD video on social media.

###

PREVIOUSLY

###

Press release from the Eureka Police Department:

The Eureka Police Department is aware that on December 24, 2025, the California Highway Patrol conducted an investigation involving Officer James Whitchurch, which subsequently led to his arrest.

Immediately following his arrest, Officer Whitchurch was placed on paid administrative leave. This is an ongoing personnel matter; the department will not release additional information at this time.

The Eureka Police Department is fully cooperating with the California Highway Patrol, which is the lead investigative agency in this matter. Any further information regarding the arrest must be obtained from the California Highway Patrol.

[Eureka Police Chief Brian Stephen said,] “The arrest of one of our officers for driving under the influence is a serious matter. This type of behavior is unacceptable and does not reflect the values, standards, or expectations of this department. We hold our members to a high level of accountability, both on and off duty. The department will address this incident through the appropriate administrative and disciplinary processes as the matter moves forward.”

Humboldt’s Homicide Rate is the Lowest It’s Been in 20 Years

Isabella Vanderheiden / Tuesday, Dec. 30, 2025 @ 1:21 p.m. / Crime

The dark blue line represents all homicide cases investigated by the Humboldt County Coroner’s Office. The light blue line represents cases within the jurisdiction of the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office. Data sourced from HCSO.

###

Humboldt County’s homicide tally hit a 20-year low this year, with three such killings recorded since the start of 2025. A fourth case remains under investigation and has not yet been ruled a homicide.

In a recent interview with the Outpost, Humboldt County Sheriff William Honsal said the county’s homicide rate has been on a downward trend for several years — despite upticks in 2020 and 2023 — averaging four to five cases per year. While three homicides were officially recorded in 2025, only one case is a “bona fide homicide,” he said.

“We technically only have one criminal homicide this year, and that was the sheriff’s office homicide investigation near Blue Lake,” Honsal said. “[The other] two cases are officer-involved shootings, which are classified as homicide, but not criminal homicide. … There’s another case that we’re assisting the Arcata Police Department on, but that has not been determined to be a criminal homicide as of yet. Really, only one bona fide homicide this year, and that is bucking the trend.”

The four homicide investigations include the following cases:

- June 5: Nicholas Anderson, 29, of Simi Valley was killed in an officer-involved shooting near the Bear River Recreation Center in Loleta. Anderson, who was in apparent medical distress leading up to the incident, was shot and killed after he allegedly rushed a deputy with a knife. In a critical incident video released after the investigation, Honsal said Anderson “held [the knife] above his head in a threatening manner,” prompting the deputy to shoot “in defense of his own life.” The District Attorney’s investigation is ongoing.

Sheriff Honsal speaks to another deputy at the scene of the officer-involved shooting near Loleta. | Photo: Andrew Goff

- July 8: Joshua McCollister, 37, of Fort Bragg was fatally shot at his home near Glendale. Following a three-day investigation, HCSO’s Major Crimes Division arrested two suspects: Arcata residents Danielle Durand, 41, and Deunn Willis, 38, both of whom were charged with murder, conspiracy and robbery. While questions remain about what led up to the fatal shooting, an HCSO press release says “preliminary findings suggest the shooting stemmed from a dispute over a civil matter involving two individuals.” The investigation is ongoing.

- July 26: Jared Nelson, 35, of Eureka was killed in an officer-involved shooting in Glendale. Deputies were in the Glendale area to serve Nelson with an arrest warrant for illegal possession of a firearm when they allegedly saw him “walk into the roadway in front of them.” Nelson fled, allegedly shooting at deputies as he ran into some bushes nearby. He was fatally shot following a brief standoff. The District Attorney’s investigation is ongoing.

The scene of the officer-involved shooting in Glendale. | Photo: Gena Bernabe

- Oct. 16: An unnamed woman was found dead in a homeless encampment in Arcata’s Valley West neighborhood. A 23-year-old man was arrested in connection with the woman’s death, and released a few days later due to insufficient evidence, according to the Times-Standard. The Arcata Police Department’s investigation is ongoing. APD did not return the Outpost’s request for additional information before publication.

In addition, there are still several missing person investigations underway that could turn out to be homicide cases.

“We have a body that was found on the Eel River early this year, and that case is still under investigation,” Honsal said. “We also have some missing persons investigations out of McKinleyville and the greater Eureka area, where we suspect the people may be deceased, but we don’t have evidence to point to [whether] they are a victim of homicide or not. We’re still investigating, and if we get evidence to prove that they were murdered, then we will pursue and request the [District Attorney’s] office to charge those cases.”

The decline in local homicides aligns with national and state statistics. In 2024, California reported its second-lowest homicide rate since 1966, according to the California Attorney General’s office. Preliminary numbers from AH Datalytics, a Louisiana-based analytics company, show a 19 percent decrease in murders in California between 2024 and 2025, which closely aligns with national stats.

Violent crimes reported in California between January and October 2025, according to data from AH Datalytics.

While homicides are often linked with substance abuse and mental health issues, no one thing causes violence to rise or fall. Honsal thinks the reason for the drop in local cases is tied to cannabis legalization.

“I’ve always equated a lot of our violent crime to illegal marijuana, and I think legalization had a big impact on us. It was legalized in 2016, and you see this trend going down to 2019,” he said in reference to the graph up top. “Robberies are down, assaults are down and homicides are down. Organized crime is not what it once was within the county. Several of our murders over the years have been directly related to marijuana rip-offs or some kind of crime related to marijuana.”

But what about the spike of 14 homicides in 2020? And another dozen in 2023? Honsal couldn’t say.

“Did it have to do with the pandemic anxiety? I don’t know,” he said. “Last year, the sheriff’s office had two [criminal homicide cases], and this year we have one.”

Attempted homicides within the sheriff’s office jurisdiction fell from 12 cases in 2024 to just two in 2025. However, assaults and rapes are up by five percent.

“I think drugs have a lot to do with it,” Honsal said. “We have a credible methamphetamine and fentanyl problem here … and the drug problem does have a direct effect on our violent crime as well.”

Turning back to the topic of missing people and cold cases, Honsal emphasized the crucial role the community plays in working with law enforcement to help move investigations forward. He pointed to the case of Emmilee Risling, a 32-year-old Hupa woman who went missing while suffering through a mental health crisis in October 2021.

“We don’t know what happened to her, but there’s a lot of speculation about what may have happened to her,” he said. “We believe people do know, but they don’t want to talk about it, and there’s other cases just like that within the county. People may have a piece of information that they can provide to us that can help break open these cases. We want to encourage people to trust law enforcement and call us if they see something.”

Those with information about any of the cases mentioned in this story or other ongoing investigations in Humboldt County can leave an anonymous message on HCSO’s Crime Tip Hotline at (707) 268-2539.

“We can’t be everywhere, and we rely on the community’s help when it comes to protecting everyone,” Honsal said. “Whatever information we can possibly get, even if it’s minimal. Whatever you know, it’s good to call us.”

Here’s Why a Jet Left Big U-Shaped Contrails Over Humboldt County Yesterday

Ryan Burns / Tuesday, Dec. 30, 2025 @ 12:01 p.m. / Hardly News

###

Hey, did you see those big U-turns in the sky yesterday? Many of you did, judging by the number of photos posted to social media.

What’s the story? Well, a subset of you will conclude with absolute certainty that the sky-donuts were composed of noxious chemicals spooged into the troposphere by nefarious globalists to control the weather/human population/our brains. Eek!

Others will reference flight-tracking websites and see that Boeing was testing one of its new 777-9s. These twin-engine wide-body behemoths are “set to revolutionize long-haul air travel” when they go into commercial service in 2027, according to at least one industry website.

This particular jet departed the King County International Airport, aka Boeing Field, around 12:30 p.m. and cruised down the coast at speeds exceeding 500 miles per hour. The pilot(s) then pulled an aerial brodie over Humboldt Bay and did a couple of laps between here and the Coos Bay vicinity before returning to Seattle shortly after 5 p.m.

When the hot, moist emissions from jet engines come into contact with the frigid air at 40,000 feet, streams of ice crystals are formed, leaving behind the long, thin trails of condensation in the sky. That’s assuming you trust scientific consensus, of course.

Watch the video below for more information and/or indoctrination.

Sheriff’s Office Announces $20K Reward for Leads in Cold Case of Missing Hoopa Woman Andrea ‘Chick’ White

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, Dec. 30, 2025 @ 9:34 a.m. / Crime , Missing

Press release from the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office:

The Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office would like to announce a $20,000 reward for information leading to the location of Andrea “Chick” White.

The reward is a combination of $15,000 from the Hoopa Valley Tribe, and $5,000 from the Bureau of Indian Affairs Missing and Murdered Unit.

White was last seen on July 31st, 1991, on Highway 299 near the Blue Lake offramp. She is described as a Native American woman, brown hair, brown eyes, approximately 5 feet tall and weighing approximately 115 pounds.

Anyone with information on this case is asked to call Cold Case Investigator Mike Fridley with the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office at 707-441-3024.