OBITUARY: Sharon Darlene Martin, 1953-2026

LoCO Staff / Friday, Feb. 13 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Our beloved grandmother, mother, sister and friend, Sharon Darlene Martin, passed away peacefully in her sleep on January 5, 2026, surrounded by love and the memories of a life well lived.

Sharon was born on September 1, 1953, to Robert and Mary Lou Dake in Blue Lake. She deeply loved her hometown and treasured the many lifelong friendships she formed while growing up there. She graduated from McKinleyville High School and carried those early connections with her throughout her life.

Sharon was married to Ralph Martin, and together they welcomed her only son, Jamie, in 1969. In 1973, she welcomed her daughter, Heidi. Later, she shared her life with Joe Luiz, and in 1978 they welcomed her daughter, Nikki. Above all else, Sharon was a devoted mother whose love for her children never wavered.

For many years, Sharon worked as an office manager at Ag Sales in Arcata, where her quick wit, humor, and kindness quickly made customers friends. She had a deep love of books and could rarely be found without one close by, sometimes finishing two or more books in a single day. She loved new beginnings, babies, animals, and tending to her plants and flowers. Gardening brought her peace and reflected the same care and patience she showed people throughout her life.

In her younger years, Sharon loved to dance and play pool and was happiest where there was music and laughter. Later in life, she cherished traveling with her sisters and cousins, where many memories were made, and she enjoyed spending time at the casino. She loved being around people, especially her grandchildren. Watching a movie with Sharon always meant hearing her commentary — often including her predictions of the ending — and her unmistakable laugh. She had a way of filling a room and making everyone feel welcome.

Sharon never met a stranger. She made people feel seen, safe, and loved. She was the kindest soul and never judged anyone. When people were nervous, stressed, or unsure, she would simply smile and say, “They can’t eat you,” and somehow everything felt easier.

She faced many hardships in life, but they only deepened her compassion and strength. Her heart remained soft, generous, and open. She welcomed countless children and friends into her home and treated them as family. She was endlessly proud of her grandchildren and loved them fiercely.

Sharon was preceded in death by her beloved son, Jamie; her partner, Terry Lawler; her parents, Robert Dake and Mary Lou and Domingo Santos; her brother-in-law, Allen Mann; and many cherished friends and family members.

Sharon is survived by her daughters, Heidi Varshock (Dave) and Nikki Naughton (Chris), and by Ariel Santos, whom she lovingly raised as her own. She is also survived by her grandchildren, who were the highlight of her life—Jaysea Jennings, Bryr Steinle (Alexis), Sydney Varshock, Cody Slater, Bryson Lawler, Kenia Robles Hernandez, Riley Lawler, Brooklyn Lawler, and Austin Lawler — and a great-grandbaby on the way. She is further survived by her sisters, Lorelei Woods (Mark), Karen Mann, and Kristina Plisik (Mike); her brothers, Rick Santos (Rebecca), Brett Santos (Suzette), and Randy Santos; her bonus sons, Tommy Lawler, Robbie Lawler, and Dustin Lawler; many nieces and nephews whom she loved dearly; along with extended family, cousins, and many dear friends who became family.

A celebration of life will be held on March 14, 2026, at 2 p.m. at Azalea Hall in McKinleyville. There will be food, music, laughter and love — just the way Sharon would have wanted it. All who knew and loved her are welcome.

Sharon will be remembered for her generous heart, her laughter, her love of books and plants, her resilience, and the way she welcomed everyone exactly as they were.

We would like to extend a very special thank you to Shonna Conner for the love, patience and unwavering care she gave our mom. We are forever grateful.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Sharon Martin’s family. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

BOOKED

Today: 5 felonies, 11 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Friday, Feb. 20

CHP REPORTS

No current incidents

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: City of Arcata Hosting ‘Water Rates Workshop’ February 25, April 15

The Atlantic: The Protein-Bar Delusion

The Atlantic: The Decline of Reading: The Orality Theory of Everything

Governor’s Office: Here’s how many medals Californians have brought home from Milano Cortina 2026 for Team USA

OBITUARY: Cathern Lee Stuefloten, 1952-2025

LoCO Staff / Friday, Feb. 13 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Cathern Lee Stuefloten, born Jan. 15, 1952, passed away suddenly on Dec. 29, 2025.

To many she was mom, grandma, sister, aunt and cousin. Everyone who knew her called her Mama Katie. She was a loving, free spirit who made friends anywhere she went.

Mama Katie was born in Woodland and she had lived everywhere between Sonoma County and Humboldt County. She loved her little dog Maple and took her everywhere with her. She loved the sun, moon and stars the most, but loved the ocean just as much. She loved to be camping in warmer places as much as she could. She loved to color and crochet. You could find her carrying either or sometimes both anywhere she went, and she loved the casinos even if she only had $1. Loved the Rolling Stones and skulls.

Mama Katie is survived by her children: Randy Crandall, his wife, Ada Crandall and their children Joshua Caswell, Jessica Crandall, Joe Crandall, and Jenna Crandall; her daughter Belinda Rivera, her husband, Rufino Rivera, their children Dustin Osborn, Theresa LaRose Ward, Sebastian Rivera and Rufino Rivera Jr.; her daughter Margaret Johnson and her children Timmy Ireland, Austyn Smith, Zeanna Johnson and Thomas Taylor-Johnson; her stepdaughter Amanda; twin sister Kathleen Phrampus and her husband, Dan Phrampus; sisters Beth Brinkerhoff, Wendy Buckley, Linda Lutz, Margie Jones, Judy Nocks; and her brother Tom Brinkerhoff. Also survived by many nieces, nephews, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and cousins.

Preceded by her mother, Patsy LeAnn Brinkerhoff, and father, Elmer Ray Brinkerhoff; her partner Tom Koontz; and her grandson Coltin Lee Osborn.

Mama Katie was cremated on Jan. 8, 2026. Anyone wishing to donate towards her celebration of life can send to her daughter-in-law Ada Crandall at $misfitcrandalls or contact by email adacrandall@gmail.com. Celebration of life to be determined.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Katie Stuefloten’s family. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

Facing ‘Extinction Vortex,’ California Grants New Protections to More Mountain Lions

Rachel Becker / Thursday, Feb. 12 @ 1:17 p.m. / Sacramento

Kittens from a local mountain lion population tracked by the National Park Service and UCLA in 2015. Photo via National Park Service

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

Just weeks after a mountain lion wandered into San Francisco, state officials voted to permanently protect populations of the charismatic predators that prowl the coastal mountains between the Bay Area and the Mexican border.

Mountain lions are one of the last big predators keeping ecosystems in balance. They feed on deer and other animals, leave scavengers, raptors and other wildlife the remains, and help maintain equilibrium among plants, prey and predator.

But, caged by concrete, killed by cars and sickened by rat poison, the isolated mountain lions along California’s coast risk inbreeding themselves into extinction, scientists and state wildlife officials say.

Members of the California Fish and Game Commission on Thursday voted unanimously to list six groups of Central Coast and Southern California mountain lions as threatened under the California Endangered Species Act.

These mountain lions account for about one-third of the roughly 4,200 solitary, tawny cats thought to roam California.

Dozens of people spoke before the board today, from ardent supporters of wildlife to fierce opponents of free roaming predators and residents of rural areas concerned for their livestock and livelihoods.

Listing the mountain lions aligns with the state’s existing ban on hunting mountain lions for sport and prohibits harming, or “taking”, them except with a permit under certain conditions. It could also increase their priority for limited conservation grants and other funds.

More importantly, advocates say, it will trigger habitat protections — including under the landmark California Environmental Quality Act.

Builders push back

State and local planning agencies must determine whether projects such as new roads, buildings or other developments could harm protected species and their habitats, and require developers to reduce that harm when possible.

For mountain lions, advocates and scientists hope that the listing will reduce further habitat loss and fragmentation in areas already carved into isolated pockets by roads and cities.

“If we want to maintain mountain lion populations in these coastal regions, then we’ve got some work to do,” said Chris Wilmers, a professor of wildlife ecology at the University of California, Santa Cruz and lead investigator of the Santa Cruz Puma Project.

Builders have challenged some of the details of the listing, but did not oppose granting the mountain lions protected status.

In a letter, the California Building Industry Association and the Building Industry Association of Southern California warned that the state’s current habitat maps could force developers in urban areas into studies and mitigation efforts that “would significantly increase project costs and schedules.”

Protecting mountain lions is a card that one wealthy Bay Area enclave has already tried to play in a gambit to block denser housing — to the scorn of housing and wildlife advocates alike.

Conflict over wildlife conflict

Ranchers and residents of hilly, remote Bay Area and Central Coast suburbs also argued that more protections could spur more mountain lion attacks on people and livestock, and harm ranchers’ livelihoods. Some sent the commission photographs of mauled cattle.

“People have them on cameras all the time eating house cats off peoples’ porches, dogs dragged off in broad daylight right in front of their owners, and children being mauled,” Greg Fontana, whose family has ranched the coastal reaches of San Mateo county for generations, wrote in a letter to the board.

It’s rare for the reclusive cats to attack people — rarer still for the attacks to be fatal. Cougars are known to have killed six people in the last 136 years — most recently a young man in 2024 in El Dorado County, outside the area where mountain lions are now listed as threatened.

Attacks on livestock and pets, however, have trended upward in recent decades, according to a state report. But state wildlife officials also note that such attacks rise for every mountain lion killed or relocated in the prior year. One theory is that younger males move into the emptied territory, where the less proficient hunters go after slower pets and livestock.

Listing mountain lions under the state’s endangered species act doesn’t prevent wildlife officials from intervening in conflicts, either, according to Stephen Gonzalez, a spokesperson for the Fish and Wildlife department. The act still allows the department to “issue permits for take of a … listed species for ‘management’ purposes,” which could include managing mountain lions that kill pets and livestock.

Mountain lions have had temporary protections under the state’s endangered species act while the state weighed whether to list them under the endangered species act. Even in that time, Gonzalez said the department has issued such permits to scare off or relocate troublesome mountain lions. It “anticipates it will continue to do so … evaluating each situation on a case-by-case basis and continuing to prioritize non-lethal methods.”

Inbreeding to extinction

Scientists and advocates say that mountain lions are running out of time: physical signs of inbreeding, including kinked tails, testicular defects and malformed sperm, have already cropped up in cougars corralled by freeways in the mountains of Southern California.

Having a kinked tail, where the end is sharply bent like an ‘L’, doesn’t seem to harm a mountain lion, Wilmers said. But they’re an ominous sign that a population is reaching alarming levels of inbreeding. Without fresh gametes swimming in the gene pool, the iconic cougars of the Santa Ana and Santa Monica mountains risk dying out in the coming decades when inbreeding starts affecting reproduction and survival, scientists warn.

Even populations further north are struggling to find mates that aren’t related to them.

The kinked tail of mountain lion P-81 is a physical manifestation of inbreeding. Photo via National Park Service

The kinked tail of mountain lion P-81 is a physical manifestation of inbreeding. Photo via National Park Service

Wilmers recalls the first time he saw a kinked tail on a trail cam in the Santa Cruz mountains. “It was definitely an ‘Oh shit’ moment,” Wilmers said. “This is really happening.”

To combat the array of threats — from inbreeding and car accidents to rat poisons and wildfires — the Center for Biological Diversity and the Mountain Lion Foundation petitioned in 2019 to add Central Coast and Southern California Mountain Lions to the state’s endangered species list.

“These populations are facing an extinction vortex,” said Tiffany Yap, urban wildlands science director at the Center for Biological Diversity. “We need these protections to get more connectivity on our roads, in our development, so that they can roam freely.”

More than six years later, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife agreed. In December, a staff report recommended that, with some tweaks to the protected area, California list these mountain lions as threatened.

Room to roam

California is already taking steps to connect cougars’ habitats — sinking millions of dollars into highway crossings to give wildlife safe passage over or under the cars and trucks that scientists report killed hundreds of mountain lions over a seven year stretch.

Yap says it’s not enough — and San Francisco’s recent visit from a cougar is a prime example. Young males disperse to find new territory and mates away from their relatives and other more dominant males.

But without paths to suitable habitat, they can find their way to Yap’s neighborhood in Pacific Heights, where the 80-pound cat ended up sandwiched in a narrow space between two apartment buildings.

Yap was across the street watching California Fish and Wildlife biologists and veterinarians from the San Francisco Zoo trying to catch the cougar, which they eventually tranquilized and released into the Santa Cruz Mountains.

To her, it drove home the importance of protecting — and connecting — the mountains the lions call home.

Wilmers agreed. “There’s always going to be mountain lions bumping into San Francisco. But right now, that’s all they can do,” he said. “We’d like to get to the place where they can find ways through this maze of urban and suburban development, to the next mountain range over.”

Lyza Padilla, Local Bassist and Center of Puerto Rican Community, Killed by Wave in Puerto Rico

Dezmond Remington / Thursday, Feb. 12 @ 11:31 a.m. / Music

Lyza Padilla. Photo courtesy of Daniel Nickerson, shot by James Adam Taylor.

An Arcata resident was swept out to sea in Puerto Rico on Monday.

Lyza Marie Padilla Coreano, 34, was hit by a 12-foot wave in the Reserva Natural Cueva del Indio in the Arecibo municipality on the north coast of Puerto Rico. She was with two other people, according to the Coast Guard; one made it back to shore, and the other was found dead during a search that covered 850 square miles. Padilla is still missing and is presumed dead.

“The Coast Guard made the extremely difficult decision to suspend our active search tonight,” said search and rescue mission coordinator Matthew Romano in a written statement. “We extend our most heartfelt condolences to the families and hope they find strength and closure during this most difficult time….This is a stark reminder to be ever vigilant while planning activities in and near the water, especially during rough sea conditions.”

Padilla played the bass guitar in the local cumbia band Makenu. Her death leaves an unbridgeable gap, her bandmates told the Outpost in a group interview.

“People will remember her as a person who inspired a lot of people, especially when we were playing,” Makenu vocalist Jaime Pierola said. “I heard a lot of friends of mine — women — who used to say, like, ‘Oh my god, I want to be her friend. I want to sing like her. I want to learn how to play the bass.’ She inspired a lot of people as a musician. [Those closest] to her will remember her as a happy person.”

Padilla was originally from Puerto Rico and moved to Humboldt in the mid-2010s. She joined Makenu when the band was founded two years ago. She was an accomplished musician — for a period, she studied at the Conservatory of Music of Puerto Rico — as well as an incessant performer. She played bass and sang for not only Makenu, but also Soul Trip, Phosphorous, the salsa group Tropiqueño, and Brett McFarland and the Freedom Riders. Makenu bandmate Daniel Nickerson estimated she played almost 60 gigs in Humboldt County last year alone. Padilla could keep large bands chugging along smoothly (Tropiqueño’s roster is large enough to take up a whole stage), even when dealing with the outsize egos that sometimes accompany the job. Makenu bandmate Johana Batera told the Outpost that Padilla was talented enough that she could have had that kind of self-importance; she chose humility instead. She could make people feel understood and heard, even when they were angry.

Pierola said when they met he felt incredibly lucky to have her in the band, both for her skill with a bass and for her presence. She had something that made people want to be around her, be with her, Pierola said; the ease with which she could lay down a bassline, glue the other members of the band together was simply a bonus. Padilla — Lyza, her friends called her — could talk and play for hours. Several of them said that their memories of her, the ones they return to time and time again, will be the simple ones when they’d sit around with a few drinks and jam and chat all night.

She was a linchpin in the local Puerto Rican community; she invited many of her friends to visit Humboldt, and many ended up sticking around. She was a proud Puerto Rican, eager to talk about “her island” and share its music.

“Lyza was pure light,” David Belmar said. Belmar is a guitarist for the local band Pichea and had known Padilla for years. “She was happiness. She was, I think, the true definition of a Puerto Rican woman. She’s a very hard working soul. She always took care of everyone. She is very talented. She’s very alive. I never saw her sad — nunca la vi triste, siempre la vi sonriendo. I always see her smiling. We all can learn a little bit from her, and we just hope that everything turns out how it needs to turn out.”

She fixed things for money, made her own clothes and sewed bikinis, and grew dozens of plants. Some she gave away (“A lot of people have her children around town,” Tropiqueño singer Rocío Cristal said), some filled her house, and many put down roots on her old Corolla’s dashboard, so many it was hard to see her when she drove it. She decorated everything, her friends said; her house was bejeweled with handmade tile mosaics, and she added flourishes to her clothing.

Her friends say it will be impossible to forget Padilla. She had no equals.

“I kind of feel like she wouldn’t want us to be sad,” Belmar said in a group interview with several friends and fellow musicians. “She’d want us to go, like, do something with our hands. Go build something. Go garden. Go make something.”

“That’s what I’m thinking about,” Nickerson replied.

It was a long time until any of them spoke again.

(VIDEO) Good Morning, America! The Sequoia Park Zoo Skywalk and Some Early-Rising Locals Made Their Debut on ABC’s Flagship Morning Program

Hank Sims / Thursday, Feb. 12 @ 11:17 a.m. / :)

One clip from today’s broadcast, queued up to the relevant moment. Rewind if you want to see some boring report about the Central Coast.

Say cheese!

This morning, as advertised, the Skywalk was featured prominently on Good Morning America, the crazy popular ABC morning magazine that your grandma still watches religiously. Correspondent Becky Worley, cheered on by locals who bothered to get up bright and early, broadcast live from the treetops throughout this morning’s program.

It’s all part of GMA’s “50 States in 50 Weeks” initiative, through which the program seeks to celebrate each of our 50 fabulous states (not Puerto Rico) on the occasion of the 250th anniversary of the founding of this amazing nation.

This means that pretaped segments from other and frankly less interesting parts of California preceded each hit from the Skywalk. But whatever, we’ll take it! Shout-out to whoever came up with the “Our Trees Are Bigger Than Yours” sign. That’ll surely drive tourism!

California Sues as Trump Cuts $600M in Public Health Grants to Four States

Ana B. Ibarra / Thursday, Feb. 12 @ 7:01 a.m. / Sacramento

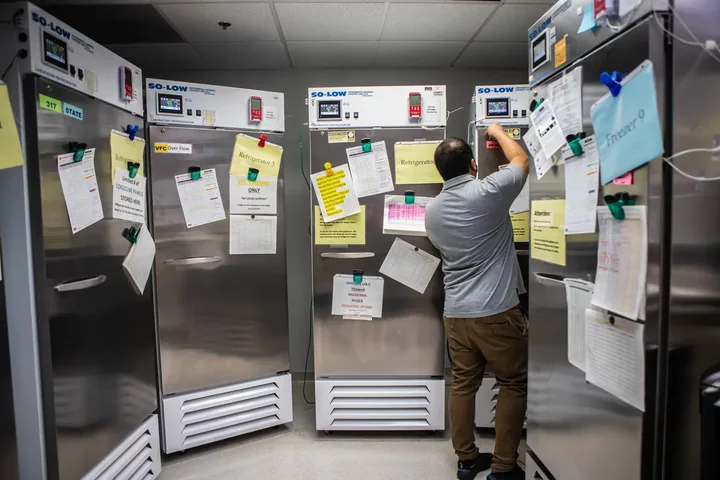

STD Investigator Hou Vang unlocks a refrigerator that houses immunizations in the Fresno County Department of Public Health on June 8, 2022. Photo by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

California is suing the Trump Administration over its plans to cut $600 million in public health funding from California and three other Democratic states, Attorney General Rob Bonta announced Wednesday.

Earlier this week, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services told Congress it would end Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grants in California, Colorado, Illinois and Minnesota. The attorneys general in those states filed a joint lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois Wednesday, arguing the cuts are based on “arbitrary political animus” and would cause irreparable harm.

The grants under threat help fund workforce and data modernization as well as testing and treatment for diseases like HIV.

The cuts target grants provided to state and local health departments as well as universities and providers. According to the complaint, one of the grants at stake is the Public Health Infrastructure Grant, considered the “backbone” of public health nationwide.

California is due $130 million from that grant, according to Bonta’s office; the money pays for more than 400 jobs, including in areas lacking healthcare workers. It also goes to update the state’s ability to send electronic laboratory data and to provide urgent dental care to underserved children, the state claims.

Meredith Reyes, a lab technician 1, labels COVID-19 swab tests before processing at the Sonoma County Department of Public Health on June 8, 2021. Photo by Anne Wernikoff, CalMatters

Losing those dollars would cause layoffs and weaken the state’s ability to prepare for public health emergencies, according to the lawsuit.

Another grant under threat, according to the lawsuit, supports planning for extreme heat events.

Other grants at risk include $6 million for Los Angeles County to address health inequities, $1.1 million that could be withdrawn from the Los Angeles County’s National HIV Behavioral Surveillance Project; $876,000 for the Prevention Research Center at USCF to address social isolation among older L.G.B.T.Q. adults; $383,000 for the Los Angeles LGBT Center, and $1.3 million for health staffing at Alameda County.

The U.S. Health and Human Services agency has not said why cuts to the Public Health Infrastructure Grant are happening only in four states, even though the program funds health departments in all 50. An agency spokesperson said only that “these grants are being terminated because they do not reflect agency priorities.”

Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi, a San Francisco Democrat, called the agency’s reasoning “a transparent excuse to punish states and communities it disagrees with, at the direct expense of lives and readiness.”

California Democratic U.S. Sen. Adam Schiff called the cancellation of grants “dangerous” and “deliberate.” “The Trump administration’s targeting of blue states is illegal and must end,” he said on X.

The California Department of Public Health and local health departments contacted by CalMatters said that they had not received official notice of the reported cuts. The Los Angeles Department of Public Health said the impact to Angelenos would be long-lasting.

“As local health departments across the nation face simultaneous health emergencies, cancelling federal investments will make our communities less healthy, less safe, and less prosperous,” the department said in an unsigned email.

Los Angeles County anticipates the cuts would undermine its capacity toIn summary The grants targeted help fund public health workforce and disease monitoring. Ending these grants could result in layoffs and worse health outcomes, according to a lawsuit filed by Attorney General Rob Bonta. respond to natural disasters and outbreaks like measles, avian flu and influenza, as well as its work monitoring sexually transmitted diseases and chronic conditions.

This isn’t the first time the Trump administration has targeted public health funding. Last spring, it tried to claw back billions of dollars from states meant to respond to public health threats, including COVID-19. A federal judge in Rhode Island ruled those cuts unlawful.

###

Supported by the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF), which works to ensure that people have access to the care they need, when they need it, at a price they can afford. Visit www.chcf.org to learn more.

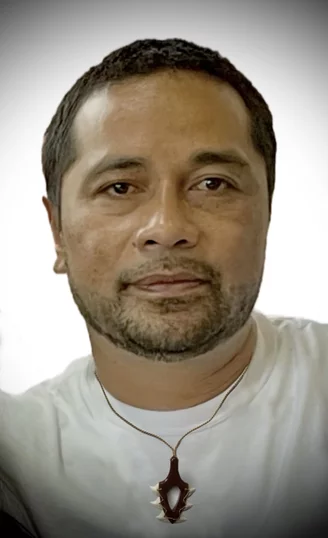

OBITUARY: Samasoni Talavou Fonoti, 1976-2026

LoCO Staff / Thursday, Feb. 12 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Samasoni Talavou Fonoti (49) of Eureka passed away peacefully on January 27, 2026 at home surrounded by his loved ones.

Samasoni was born on January 30, 1976 in Pago Pago, American Samoa at LBJ Hospital in Faga‘alu village to Fa’apisa Togafau Talamaivao and Toga La‘u Fonoti Sr. He was raised in Samoa until the age of 11 — a place that deeply shaped his values, strength and lifelong devotion to his family, faith and culture. He carried his Samoan heritage with pride everywhere he went, grounded in respect, solid in values, always putting family first, and carrying himself with dignity and purpose.

Growing up with a competitive spirit, Samasoni stayed active playing the sports he loved: baseball, basketball, football, and rugby. In 1987 he traveled with the American Samoa Youth Baseball Team to Honolulu, Hawai‘i. He remained there and lived with Aunty Isu Miller and her family who welcomed him with love and guidance. He attended Alva Scott Elementary School and ‘Aiea High School, graduating in 1994. During his years in Hawaii Samasoni continued to grow both academically and personally, forming lifelong friendships, deepening his sense of responsibility and independence.

In 1998, Samasoni moved to Eureka with his father and little brother to attend College of the Redwoods and live alongside his older brother, Toga Fonoti Jr. Soon after, he met his wife Keaka (Roberts) Fonoti, and they were blessed with seven children: Talimaivou, Fa’apisa, Malia, Puletele, Tamasili, Samasoni Jr., and Kalea Fonoti. His children were his greatest joy. He took immense pride in each of them, always encouraging, teaching, and supporting them along the way. Samasoni was the foundation of his family, leading with integrity, wisdom and a strong work ethic that spoke louder than words. His family was the center of his world and everything he did was for them.

Throughout his life, he delivered newspapers, worked at Daiei Market, JCPenney, Sequoia Park Zoo, Costco #125, and in 2020 established his own restaurant. Island Delight held a special place in his heart for the following four years. He was deeply involved in every aspect and took great pride in running his family-owned business. He personally perfected his authentic Hawaiian recipes such as his Onolicious Chicken Katsu and Sweet and Sour Spareribs, along with his homemade sauces (all made from scratch with lots of love). These quickly became favorites among customers who raved about the tasty flavor. Cooking and sharing food became another way for Samasoni to connect with people, express his culture and give to others.

Samasoni will be remembered as a man of dedication, generosity, strong will and kind-heartedness. His laughter filled rooms. His wisdom carried others forward and in a life shaped by humility he listened more than he spoke. Though our hearts are heavy we take comfort in knowing he passed surrounded by love and is welcomed with open arms in Heaven.

Samasoni is survived by his loving wife, Keaka Fonoti; his children Talimaivao Lokomaikaiokalani Fonoti, Fa’apisa Peleina Fonoti, Malia Atamai Fonoti, Puletele Talila Fonoti, Tamasili Fa’asoa Fonoti, Samasoni Makanatogiola Fonoti Jr. and Kalea Laginatia Fonoti; and his siblings Mila Fonoti, Fiti Fonoti, Sally Fonoti, Toga Fonoti Jr. and Susie Fonoti. He was preceded in death by his parents, Toga La‘u Fonoti Sr. and Fa’apisa Togafau Talamaivao, and his younger brother Talavou Fonoti.

Services will take place on Friday, Feb. 20, at:

The

Church

of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

2806

Dolbeer St., Eureka, CA 95501

Viewing: 9 a.m.

|

Service: 11:30 a.m.

Burial:

2 p.m. at Ocean

View Cemetery, 3975 Broadway, Eureka.

In lieu of flowers, to honor Samasoni’s life and legacy, a fund has been set up to support his family. Monetary donations are deeply appreciated and will help assist the loved ones he devoted his life to.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Samasoni Fonoti’s family. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.