Last week, people around the world were having lots of fun with the North Coast Journal’s big scoop. That scoop was: A woman who was reported missing in Humboldt County while supposedly working at a weed farm a few months ago, and who was included on state and local lists of missing persons, was located by one of the NCJ’s own Facebook friends, safe and sound, on a major reality television show.

Fun! This was a fun story. It was made yet more fun by a press release the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office issued in the aftermath. The press release laid out in great detail the Rube Goldberg-like chain of events that left Rebekah Martinez on the Sheriff’s Office missing persons list, even though, in the intervening months, her family had reported her safe and sound, and even though millions had since been bewitched by her pixie haircut – the first in the 21-season history of The Bachelor, as The New York Times informed us.

Strangely, though, the Journal seems not to find all this as fun as everyone does. And that is because it believes that the fun obscures the splashy investigative work featured in this last week’s issue — and now this week’s — which purports to explore what the Journal calls “the highest rate of missing persons reports in the state.” This is a number that the Journal wants you to be troubled by.

Writer

Linda Stansberry explains her disappointment with the fun machine

here:

Our small, rural county HAS 👏THE 👏 HIGHEST 👏 RATE 👏OF 👏 MISSING 👏PERSONS 👏 REPORTS 👏 PER 👏 CAPITA 👏 IN 👏THE 👏STATE. This is the story. This is why I do my job. https://t.co/fsFo8xxuZd

— Linda Stansberry (@LCStansberry) February 2, 2018

Did that get your attention? Good. Then click on the Journal’s story, there, if you haven’t yet, because it is a pretty nifty story that, apparently against its own author’s wishes, shows that a statistic like “highest missing persons reports per capita” is just about meaningless, especially when taken out of context. Subsequent events – the unearthing of Rebekah Martinez and two more of what the Journal had dubbed the “Humboldt 35,” one of them a guy found living here in Eureka blessedly ignorant of his own missingness – have underscored this point handily. It’s strange that the Journal resists the conclusions of its own reporting.

An actual missing-persons cold case is one of the most heartbreaking and terrifying things imaginable. The Journal illustrates such cases in all their terribleness very well, both in this week’s issue and last week’s.

However, the Journal does those cases a disservice when it tries to make them illustrative of missing persons reports, which come and go as cheaply as you please. Rebekah Martinez is far more emblematic of those reports than any actually missing person. It’s hard to clap for attention, though, when your story is mostly about California’s highest rate of people who don’t return their moms’ phone calls.

###

The Journal’s reporting leans hard on two sets of data. They are both flawed by nature, they became more flawed through the Journal’s incomplete and sometimes erroneous reporting, and they barely have anything to do with one another.

The first set is the number of people reported missing in counties across the state, per capita, since 2000. “Missing persons reports,” as the Journal wrote, are filed in any number of cases — runaway kids, people hiding from their exes, people killed in catastrophic events, people with a simple desire to be off the grid for a while. All it takes is someone not able to find someone else, and a phone call to a law enforcement agency.

Humboldt has the highest per-capita rate of such reports. That’s true, and that’s the nut of the Journal‘s reportage.

But you know what else Humboldt County had the highest rate of, over that period of time? It had the highest per-capita rate of found people. Far more people were found here, per capita, than anywhere else in the state.

| HUMBOLDT | 670.1 | 1st |

| TULARE | 640.1 | 2nd |

| MERCED | 613.9 | 3rd |

| KERN | 608.8 | 4th |

| STATE AVERAGE | 361.9 | — |

| RIVERSIDE | 355.4 | 30th |

| SAN FRANCISCO | 337.0 | 34th |

| LOS ANGELES | 300.4 | 42nd |

Yowza. We sure do find a lot of people! That’s better than 85 percent more than the statewide per-capita rate of found people. For all the time and energy the Journal expended on the number of missing persons reports, it’s odd that it never chose to share these numbers — about the resolution of those reports — at all.

You might think: Hey, so a lot of people are reported missing here, and a lot of those people are subsequently found here. So maybe everything balances out?

It more than balances out. In point of fact, we do much better at finding missing people than the state as a whole does. Here is a table of selected California counties ranked by their rate of missing persons cases filed that are unresolved by the end of the year:

| IMPERIAL | 11.2% | 1st |

| FRESNO | 10.8% | 2nd |

| ALPINE | 10.7% | 3rd |

| SAN BERNARDINO | 10.5% | 4th |

| STATE AVERAGE | 6.9% | — |

| NAPA | 5.7% | 33rd |

| HUMBOLDT | 5.7% | 34th |

| KERN | 5.6% | 36th |

| MENDOCINO | 5.2% | 39th |

Not too shabby. Despite the volume of calls our county handles (per capita), Humboldt clears its missing persons reports about 17 percent more often than the state as a whole.

And now you might think: OK, so we’re actually doing a lot better than the rest of the state, comparatively speaking, but 5.7 percent of missing persons reports not cleared is still a lot of missing people here in Humboldt.

And that would be a lot of people — about 54 per year — were that the case. You’d be forgiven for thinking it’s the case if you only got your information from the Journal, which wrongly refers to these as “open cases” in one of the graphs in this week’s paper, which is also one of the few places the Journal references statistics on found people at all. [See correction, below. — Ed.]

They are not open cases, though. Please refer to the fine print in the tables above. These are open cases plus cases that were opened and then closed in different calendar years. As the Attorney General’s missing persons page puts it:

The statistics in the following reports are gathered from missing person entries and cancellations made by law enforcement agencies in the Department of Justice (DOJ) Missing Persons System … The counts for each of the ‘status’ reports is based on cancellations during the same year the entry was made.

The Outpost followed up with the AG’s office this week to make sure that this says what it seems to say — that the “status” reports, or the reports on missing person cases closed — apply only to people lost and found in the same calendar year. It does.

So from the outside we have no way of knowing how much of each category — still-missing persons, people since found — are lumped into that number. That’s a serious flaw in the statistics we have about actual missing person cases. But it’s a pretty safe bet, given how often we find people in the calendar year, that many or most of them fall into the latter category. You already know about three such cases — Rebekah Martinez and her two fellow members of the “Humboldt (formerly) 35.”

Because the Journal doesn’t talk much about the missing persons reports that have been closed — however imperfect that data is — it doesn’t have much to say about the state those people were found in. It does talk, at one point, about the people found dead, presumably because that sounds scary, but the overwhelming majority were just fine. Here are Humboldt County’s numbers from 2017, which are representative:

| RETURNED | 177 |

| LOCATED | 119 |

| DECEASED | 7 |

| ARRESTED | 7 |

| VOLUNTARILY MISSING | 23 |

| WITHDRAWN/INVALID | 10 |

| OTHER | 42 |

| UNKNOWN | 1 |

| TOTAL | 386 |

To sum it up: 429 times last year, someone called up one of Humboldt County’s law enforcement agencies to report someone missing. In 386 of those cases, the person was found within the calendar year. In seven of those cases, the person was found dead — either from suicide, foul play, tragedy or simple, unsuspicious death — and in every other case the person was alive and (probably) well.

Forty-three of those people were not found before New Year’s Day, which represents a much lower ratio of cases unresolved by that deadline than could be found in the state as a whole. One of them was a burgeoning reality show superstar. [See correction number two, below. — Ed.]

###

Spend some time with these numbers, and you’ll see why it’s puzzling that the Journal basically only chose to share one side of the story the numbers tell with its readers (the high proportion of cases filed, compared to other counties) without telling the other side (the even higher proportion of cases resolved).

But it’s even weirder that the Journal places those record statistics alongside stories of people who have actually gone missing and stayed missing over the years. We’re talking about cold cases, rather than surly teenage runaways who shamble back home after a few hours or freespirited young folk up in the hills and off the grid.

The headline of the Journal’s first story was “The Humboldt 35: Why does Humboldt County have the highest rate of missing persons reports in the state?” Reading it like that, you’d think the two things have something to do with one another. They really don’t. The first part is about the horrifying cases that leave families in a state of emotional paralysis; the second part — as we saw above — is almost all about people who are not missing for very long.

“The Humboldt 35” came from the second set of data that the Journal relied upon for their story — a non-comprehensive list of missing persons cases, spread out over a number of decades, that the state attorney general chose to feature on its website. There’s no reason to think that these 35 — now 32 and falling — represent a higher proportion of actual cold-case missing people than the state as a whole.

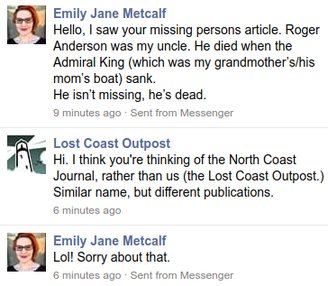

A Facebook message the Outpost received Wednesday.

And even if it feels like a high number to you, you should be aware that it doesn’t represent what you and I — and the families of the people listed — might think of as “missing person cases,” or Humboldt County missing persons cases. A number of the people listed there are people known for certain to be dead, either through violence or tragedy. At least two of them were lost at sea. They’re included in the “missing persons list” because their bodies were never found — a tragedy, certainly, but a tragedy of a different sort than a family left in uncertainty. Another of them went missing in Nevada, but gets lumped into Humboldt County’s missing person list because he was from here.

All this is only to underline the fact that the statistics we are given to work with here are really sloppy and bad, and that when they do say something they often say the opposite of what the Journal seems to want them to say.

The Journal, on its face, wants them to say: Look at these missing people. See their pictures. Read their names. We have the highest rate in the state.

#Humboldt County has the highest rate of missing persons reports per capita in the STATE. To research this story our data guy @tngliker went through tons of reports and found some crazy, troubling numbers.

— Linda Stansberry (@LCStansberry) February 2, 2018

I talked to family members whose sons, daughters, brothers, children have been missing, some for decades. They want answers. I tried to give them answers.

— Linda Stansberry (@LCStansberry) February 2, 2018

But what the numbers say in fact, when you add in the ones that the Journal chose not to share and correct the ones it misread, is: A lot of people file missing persons reports in Humboldt County. Fortunately the vast majority of them end happily, as best we can tell, and we clear them up at a pace that far exceeds the state average.

The Journal’s efforts to bring public attention to the cases of people who have gone missing in suspicious circumstances — Jeff Joseph, Sheila Franks, Robert Tennison and others — is obviously laudable.

Less laudable is its impulse to tart up the incidence of such cases with incomplete, misread and unrelated statistics in order to imply that the Journal has uncovered a troubling trend looming underneath the Humboldt County fog. That’s not what the statistics say at all.

###

CORRECTION: Journal graphic designer Jonathan Webster tweets us to let us know that he got the “open cases” number not from the data we had assumed he had — the attorney general’s hard data about missing persons cases resolved in the same calendar year — but from the same list of missing persons cases featured on the Attorney General’s website that resulted in “the Humboldt 35.”

In a way this is even more problematic, especially when you attempt to use it to compare statistics from county to county, as it is does not purport in any way to be representative of actual “open cases.” It says right there at the top: “DATA LIMITATIONS: This database is a subset of all persons reported as missing by law enforcement in the State of California” (emphasis added). Nevertheless, we regret the error!

###

CORRECTION 2: Journal graphic designer J-Web catches another boo-boo! Though the Humboldt County rate of resolving cases was, in fact, 17 percent higher that the state as a whole over the 18-year period covered in the chart above, Humboldt’s rate of resolving such cases was actually lower than the state’s in calendar year 2017 — numbers from which were unavailable at the time of the Journal’s original story. Error once again regretted. [Addendum: And Webster wants you to know that it was also lower that the state’s in 2017 when only considering adults, too, which is the boo-boo he originally noticed.]

CLICK TO MANAGE