OBITUARY: Brian Wayne Billings, 1985-2025

LoCO Staff / Friday, Feb. 14, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Brian Wayne Billings, born July

24, 1985, took his journey home on February 5, 2025.

There was never a day that he wasn’t working. He started working at the local store when he was 17 years old through CIMC, and he continued to work at other places in customer service. He worked at Lucky Bear Casino, Ki:ma’w Medical Center, Joe’s Deli, Straight Arrow, Hoopa Mini Mart, Hoopa Elementary School and the Hoopa Grocery Store. He had a heart for giving and always wanting to help where he could. He was an ordained Assistant Minister for the Hoopa 1910 Indian Shaker Church. He traveled to Shaker churches in Washington, Oregon and California with his beloved Mama. He was always willing to take a ride and enjoyed the time spent cruising.

When he wasn’t working, he enjoyed spending time playing video games, dice and card games with his friends and family. His culture and language were important to him and he continued to share it with those close to him and took pride in the dances. He was a die-hard Dallas Cowboys fan. He was known to many as BS Billings with his quick wit and the ability to keep a straight face even when he knew he was full of it.

He is preceded in death by his Mama Gloria Billings, Uncle Keith Baldy, Father Floyd Billings Jr., Mother Leandra Billings, and his namesake Uncle Wayne Grant.

He is survived by his only son Brian “Beans” Billings II, his Grandma Vi Masten, his uncles Oscar “Tyke” Billings (Lori), Richard Billings, Ed Masten, Elrod Masten (Susan), Hank Masten, Thomas Masten, his aunts Terry “Suzie” Hall (Rick) and Debbie Billings-Baldy, his brothers; James “Scuffer” Rickaby (Kristen), Floyd “Cowboy” Billings (Amber); his Sisters; Gina Rickaby-Cote’ (Jeremy), Jacklin Billings, Darcy Padilla (Brian) and Ruby Mularky (Mikey) along with numerous nephews and nieces.

Pall Bearers: Cowboy Billings, Brian Padilla Jr., Mikey Mularky, Adam Martin, Dana Chisum Jr., Lyle Elvis Baldy Jr., Leroy Baldy, James McCovey, Lance Teodecki, David Ruiz Sr., Ricky Hall, Alex Bristol, Jeremy Cote’, David Ruiz Jr., Darius Ruiz, Thomas Billings, Trystan Billings and Torin Billings.

Honorary Pall Bearers: Oscar “Tyke” Billings, Richard Billings, Ronnie Robbins, Ed Masten, Elrod Masten, Hank Masten, Thomas Masten, Rick Hall, Mike Mularky, Robbie Morrill, Gabe Cervantes, Jody Jackson, Tyson Dempewolf, Infallible Ausenbauer, Warren Tamerius and Anthony Risling,

There will be a wake at his residence on Telescope Road Friday, February 14, 2025 starting 6 p.m. Funeral Services Saturday February 15, 2025 at 11 a.m. at the Neighborhood Facilities, officiated by Rodney E. Vigil Sr. Burial immediately following to be held at Bald Hill Family Cemetery and Reception will be at the Fire Hall.

Arrangements are under the care of Paul’s Chapel, Arcata.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Brian Billings’ loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

BOOKED

Yesterday: 4 felonies, 11 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

1740 Mm96 E Hum R17.40 (HM office): Traffic Hazard

Myrtle Ave / Harrison Ave (HM office): Defective Traffic Signals

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Wet Winter, Dry Reality? Humboldt Officials Say Water Risk Isn’t Gone

RHBB: College of the Redwoods Del Norte Campus Project Moving Forward with Measure I Funding

RHBB: Major Roadwork Scheduled Friday, February 6 through Thursday, February 12

Fishing the North Coast : Finally — Rain on the Way for North Coast Steelhead Rivers

‘Our Roads Absolutely Suck’: Supervisors Debate How to Prioritize Spending Revenues From Measure O, the New Countywide Sales Tax

Ryan Burns / Thursday, Feb. 13, 2025 @ 2:42 p.m. / Local Government

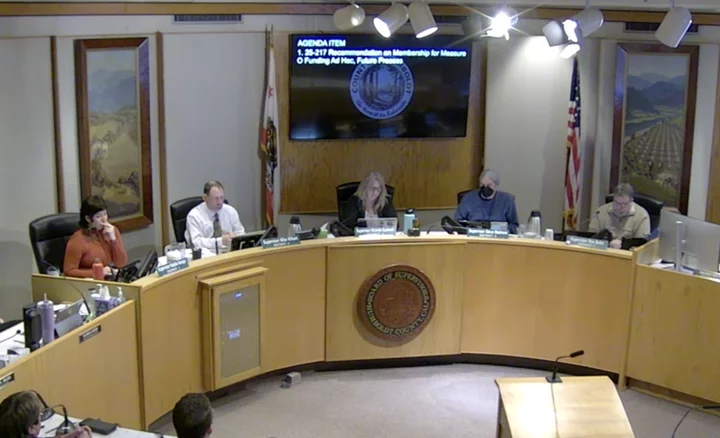

The Humboldt County Board of Supervisors (from left): Fourth District Supervisor Natalie Arroyo, Third District Supervisor Mike Wilson, Second District Supervisor and Board Chair Michelle Bushnell, Fifth District Supervisor Steve Madrone and First District Supervisor Rex Bohn.

###

Back in November, more than 63 percent of Humboldt County voters approved Measure O, aka the “Humboldt County’s Roads/911 Emergency Response Measure,” ushering in a new 1 percent sales tax countywide (including within our incorporated cities).

The measure is expected to generate $24 million per year, and on Tuesday, the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors debated how to prioritize spending those revenues, with First District Supervisor Rex Bohn advocating hard for spending the vast majority — if not all — of it on road repairs, rather than public transit.

“Our roads absolutely suck right now,” Bohn said at one point in the meeting. He said he regularly gets calls from constituents complaining about potholes and the general state of disrepair of county roadways, “but I don’t get any calls on transit.”

Other supervisors — particularly Fourth District representative Natalie Arroyo and Third District representative Mike Wilson — said that while roads should certainly get the biggest chunk of Measure O revenues. public transit initiatives deserve a cut, too.

Such spending decisions will need to be made each year, and Tuesday’s board discussion also focused on reviewing the process for those future deliberations, which will involve oversight and input from an audit committee, technical committees, county department heads and the Humboldt County Association of Governments (HCAOG).

Way back in July, when the board unanimously agreed to put Measure O on the ballot, it promised to appoint a “Funding Workgroup,” or ad hoc committee, with representatives from the county (including two supervisors, the Public Works director and someone from the County Administrative Office) as well as outside agencies such as HCAOG, the Humboldt Transit Authority and the McKinleyville Community Services District.

The recommendation presented by staff on Tuesday also called for the inclusion of representatives from the the Building and Construction Trades Council of Humboldt and Del Norte Counties and the Humboldt Builders’ Exchange. Wilson questioned this late addition.

“What expertise do those organizations bring to this discussion in terms of how we allocate community funding — prioritizing where transportation dollars get spent?” he asked. “Like, what’s that about?”

County Administrative Officer Elishia Hayes said it’s entirely up to the board, who gets put on this committee, and it will ultimately be up to the board alone to make allocation decisions. The ad hoc committee, which is only scheduled to meet one more time before the first spending decisions are made, will only set broad expectations, she said.

Wilson remained hesitant.

“I agree with you that the ad hoc [committee] is not necessarily super deep, but it’s still a vibe,” he said.

Fifth District Supervisor Steve Madrone said the group’s directive will be limited to recommending how to split revenues between transit and roads, “nothing more.” By way of example he threw out some hypothetical percentages — 20 or 30 percent to transit, or maybe 60 or 70 percent to roads.

The prospect of giving that much to transit — even hypothetically — appeared to irk Bohn. He noted that local transit agencies have received close to $35 million in grants over the past year and suggested that road repairs should be a much higher priority.

“I have roads failing everywhere; [Second District Supervisor] Michelle [Bushnell] has roads failing everywhere,” Bohn said, referring to conditions in their respective districts. He argued that the Measure O sales pitch to voters focused heavily on roads. “Our roads are terrible,” he said.

Madrone and Bushnell have been the county’s representatives on the Measure O ad hoc committee thus far. Madrone asked to continue serving in that role, and he described himself as an advocate for both roads and transit. He advocated spending “an appropriate level” of Measure O revenues on transit, suggesting perhaps 20 percent.

“We got a lot of money to work with,” he said. “We’ll figure it out.”

Wilson said that, unlike Bohn, he has heard constituents advocate for improved public transit, with public polling reflecting that interest.

Bohn, clearly frustrated, stuck to his guns, saying roads should receive all or nearly all of the funding for at least the next three years. In his view, that’s what voters wanted when they passed Measure O.

“I’m just saying, can we just agree to spend the money where we said we were going to spend it, instead of diverting it?” Bohn said. “What I’m saying is our roads are bad, and I think people jumped on this because our roads are bad.”

Fourth District Supervisor Natalie Arroyo replied, “I am absolutely in favor of the vast majority of this going to road repairs,” though she added that, as both the chair of the Humboldt Transit Authority and the board’s representative for most of the City of Eureka, she’s heard from many people who voted for Measure O because of its inclusion of public transit funding.

Bushnell wound up making a motion to appoint the staff-recommended list of people to the ad hoc committee, though she suggested replacing herself with Wilson as the board’s representatives. The motion passed 4-1, with Bohn dissenting.

Before the vote, Bohn argued his position one more time. “I want transit to be funded … ,” he said, “but our roads are failing, and they’re going to do nothing but get worse if we don’t do anything.”

Eureka Joann Fabrics One of Hundreds Across the Country Slated For Closure

Andrew Goff / Thursday, Feb. 13, 2025 @ 11:15 a.m. / Business

Photo: Andrew Goff.

This might be a good day to check in on the local sewers, quilters, crafters, cosplayers and DIY home decorators in your life. They may be in mourning after news that the Eureka Joann Fabrics is one of the chain’s roughly 500 locations slated for closing.

Wednesday’s announcement from Joann Fabrics comes nearly a year after the retailer — which was founded in Cleveland in 1943 — declared bankruptcy, citing higher overseas shipping costs and declining consumer demand.

The 500 Joann Fabric locations scheduled for closure represent more than half of company’s locations. In our region, the Eureka store’s fate is shared by stores in Redding, Chico, Klamath Falls and Grants Pass. The Medford location will be spared for now.

Joann Fabrics has not given an exact date for when its stores will shutter.

California City Makes ‘Aiding’ or ‘Abetting’ a Homeless Camp Illegal

Marisa Kendall / Thursday, Feb. 13, 2025 @ 7:40 a.m. / Sacramento

The Fremont City Council gave final approval this week to an ordinance that bans camping throughout the entire city, while also making anyone “aiding, abetting or concealing” a homeless encampment guilty of a misdemeanor.

The aiding and abetting clause has sparked alarm from local outreach workers who worry they could be targeted for helping people living in camps, and experts in homelessness law who say they’ve never seen anything quite like it in California. Council members considered changing that part of the ordinance Tuesday night, but ultimately passed it as-is 6-1.

“Our public spaces belong to the entire community and it’s really not compassionate at all to cede our public spaces to a select few individuals at the expense of everyone else in the general public,” said Councilmember Raymond Liu, who voted in favor. “Families should be able to take their children to the parks, to the libraries, without fear, and all residents should be able to use our public spaces without encountering any unsafe conditions.”

Council members discussed the camping ban at length in a five-hour meeting Tuesday, where nearly 200 people lined up to speak for and against the measure during public comment. It was an unusual amount of fanfare for an ordinance that the city council already passed once earlier this month – Tuesday’s vote was a “second reading,” which typically is just a formality that warrants no discussion.

But the controversy surrounding the ban, which prohibits camping on all sidewalks, streets and parks in Fremont and makes anyone who aids or abets such a camp subject to a $1,000 fine or six months in jail, prompted the City Council to reevaluate the ordinance.

Three council members, plus the mayor, expressed interest either in removing the aiding and abetting clause or adding language to specify that it wouldn’t be used to punish people for handing out food, water and other essentials in homeless camps.

That change seemed likely to go through until minutes before the final vote. But after City Attorney Rafael Alvarado said multiple times that the aiding and abetting clause would target people who help unhoused people set up illegal camps, not people who give out food, council members changed course. Ultimately, they passed the measure as-is.

Changing the language would have forced council members to re-introduce the ordinance, meaning they’d have to go through two more votes. By the time the City Council voted Tuesday, it was almost midnight.

The text of the ordinance doesn’t specify what qualifies as aiding, abetting or concealing a homeless encampment. That leaves some uncertainty as to how the ordinance will be enforced, despite Alvarado’s assurances, UC Berkeley Law professor Laura Riley told CalMatters.

“That might be their stance at the time of adoption,” she said, “but there’s nothing in the language of the ordinance itself that prevents targeting people from doing things as humane as giving unhoused people tarps when it’s raining.”

In practice, local police often determine how they will enforce an ordinance, Riley said. How the Fremont aiding and abetting clause is interpreted could change when the city’s leadership changes, she said.

The city attorney’s statements were small comfort to Vivian Wan, CEO of Abode Services, which provides food, tents, clothing and other services to unhoused people living in camps.

“We worry about the ‘concealing’ portion, as PD/City staff in Fremont have been known to pressure us to share confidential information, including where a participant is staying,” she said in an email to CalMatters. “I think this ordinance may be used to compel such information, breaking the trust with folks that often takes years to build.”

The measure also puts the city of Fremont at odds with the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern and Southern California, which, in a letter to council members signed by several other aid and human rights groups, said the aiding and abetting clause is “patently unreasonable and will expose the City to legal liability.”

More than two-dozen California cities and counties have either passed new ordinances or beefed up old ordinances banning camping in recent months, after the U.S. Supreme Court gave them more freedom to do so. But none of those bans appear to include specific language that makes it a crime to aid or abet a camp.

In a statement to CalMatters, the Fremont city attorney’s office said the aiding and abetting language is nothing new – it’s already illegal in Fremont, as in many cities, to aid or abet any crime. When asked about that by council members during Tuesday’s meeting, Alvarado said even if the new camping ban didn’t have that specific clause, “in theory,” someone could still be penalized for aiding and abetting a homeless encampment.

But Riley said it’s significant that the new camping ban explicitly makes it a crime to aid and abet an encampment – language she’s never seen in any other active camping ban in California.

“This does seem to be going further,” she said. “Because by making it explicitly tied to this section of the code, to me, it signals that there is intent to prosecute under this section.”

Legal experts CalMatters spoke with said this is extremely unusual. No other city, to the best of CalMatters’ knowledge, has attempted to use general municipal code in the fashion this ordinance would.

More than two-dozen California cities passed, strengthened or are considering ordinances that penalize people for sleeping outside, after the U.S. Supreme Court allowed cities to crack down.

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

California Court Rules Against Baker in Revival of Same-Sex Wedding Cake Disputes

Jeanne Kuang / Thursday, Feb. 13, 2025 @ 7:33 a.m. / Sacramento

Photo by Brent Keane via Pexels.

A Kern County baker violated California law when she refused to sell a cake to a lesbian couple for their wedding, a state appeals court ruled this week in a suit brought by the state’s Civil Rights Division.

If the scenario sounds familiar, that’s because it’s central to a series of cases that have for years been shaping the nation’s legal debate over free speech and anti-discrimination laws.

In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a Colorado ruling that a baker had violated that state’s nondiscrimination law when he refused to bake a cake for a same-sex couple’s wedding. The ruling was based on the court’s finding that the Colorado civil rights commission handling the case had been prejudiced against the baker’s religious beliefs.

The court in 2023 ruled, also in a Colorado case, in favor of a website designer who opposed same-sex marriage on religious grounds and who was afraid the same state statutes could in theory force her to design a wedding website for a gay couple. That would violate the designer’s First Amendment rights to free expression, the Supreme Court ruled in a decision that LGBTQ rights activists said could open the door to more discrimination in public spaces.

The California decision this week draws boundaries on what counts under a business owner’s right to free expression.

In a statement, California Civil Rights Commission director Kevin Kish praised the ruling for upholding “the longstanding principle guaranteeing all Californians full and equal access to services and goods in the marketplace.”

The case stemmed from the marriage of Eileen and Mireya Rodriguez-Del Rio, who visited Tastries bakery in Bakersfield to buy a cake for their wedding in August 2017.

The couple spoke with an employee and selected a pre-designed plain, white, three-tiered cake that the bakery often sells for various celebrations including birthdays and baby showers, according to court filings. When the couple returned with friends and family for a tasting the following week, Tastries’ owner Catharine Miller refused to sell the cake upon learning it would be served at a same-sex wedding.

Miller is a devout Christian who also refuses to make cakes depicting marijuana use or sexual imagery. She later told the courts she has a bakery policy stating that “wedding cakes must not contradict God’s sacrament of marriage between a man and a woman.”

The couple filed a complaint with the state Civil Rights Division, which sued Miller in 2018. Miller, who is represented by the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, argued her policy was based on her religious beliefs about marriage, not animus toward LGBTQ people.

A Kern County judge sided with her, ruling that Miller’s policy did not violate the state’s Unruh Civil Rights Act because it applies to all customers, and because Miller referred the couple to another bakery that had previously agreed to sell cakes to same-sex couples (but which the Rodriguez-Del Rios had already ruled out).

The state appealed the decision last year, and a three-judge panel of the 5th Appellate District reversed it in a unanimous ruling.

The judges ruled Miller’s policy is not neutral because it could only apply to customers on the basis of their sexual orientation. They also ruled that reproducing a plain cake with no writing or decorations that Miller would have sold to anyone else does not count as being forced to express support for a same-sex wedding.

“Drawing the contours of protected speech to include routinely produced, ordinary commercial products as the artistic self-expression of the designer is unworkably overbroad,” the judges wrote.

Miller, through a spokesperson at the Becket Fund, declined to comment. In a statement, her attorney and Becket Fund vice president Eric Rassbach said Miller would continue to run the bakery while they appeal the decision to the state supreme court.

“This case is not just about Cathy Miller — it’s about protecting the rights of all Americans

to live and work according to their deeply held beliefs,” said another of her attorneys, Charles LiMandri. “We will continue to fight in the courts on Cathy’s behalf to ensure that the freedom to live out her faith through her creative work is upheld and that justice is fully served.”

The case could be primed for more appeals by conservative legal groups that ultimately seek to extend the Supreme Court ruling in the Colorado web designer case and establish exceptions to anti-discrimination laws allowing businesses to refuse services to gay Americans, said Matt Coles, a law professor at UC Law San Francisco.

But he said the California ruling makes important distinctions between designing a wedding website and making a standard cake.

“This was not a great case for them,” Coles said. “The challenge in this case was, how do you draw a line between stuff that’s clearly speech or expression, and stuff that’s clearly not? If what you’re selling is some kind of generic cake, you don’t have 1st Amendment claims.”

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

OBITUARY: Kenneth Lee Rose, 1969-2025

LoCO Staff / Thursday, Feb. 13, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

It

is with the heaviest of hearts that we announce the passing of

Kenneth Lee Rose of Rio Dell. He was known by many names to those who

loved him — Baby, Honey BunBun, Dad, Opa, Kenneth Lee, Kenny,

Rosebud and Wolfie, to name a few.

Ken was born to Carl and Nancy (Cowart) Rose on December 16, 1969. He was the fifth child and last son born to Carl and Nancy. He grew up in Fortuna and Hydesville, attending what was then known as Town School, Hydesville Elementary, Fortuna High School and East High. Some of his favorite childhood memories were spending time with his brothers and friends on Vancil Avenue in Fortuna, playing in the woods.

In 1984, Ken met the love of his life, Cindi Mock. They spent his freshman year riding around Hydesville and Carlotta on his dirt bike, getting gas at the old Murrish Market before riding on the river bar at the end of Fisher Road, exploring the trails and woods around Martin and Shirley’s, Fox Creek Road and Starvation Flats. They separated when Cindi graduated from high school. When Ken was 16, he and Brenda Beebe became parents to his first son. Ken quit school and went to work as a timber faller. He then went on to work at Humboldt Printing and then Pacific Lumber Company. He married Carrie Stephens in 1991 and they became parents to Ben, Amy and Matthew. After Ken and Carrie divorced, he and Monica Warden had a son together.

Ken and Cindi reconnected after both divorced their spouses and were married on May 3, 2008. They both said it was like no time had passed while they were apart and they picked up their friendship and romance right where they had left off. They liked to share that they were high school sweethearts; they knew God had made them for one another. During their nearly 18 years together, they built a life they both loved. They started a firewood business, Log Dawg Firewood, in 2020. While the rest of the world was shut down, Ken and Cindi spent countless hours in their truck and in the woods making firewood. Some of their best times were spent being surrounded by nothing but trees and God’s creatures.

Although Ken liked to complain that Cindi was crazy and she didn’t have to sing quite that loud in the truck, he always tuned the radio to the oldies station so she could sing along with the songs from the 1970s and 1980s. In the following years, anytime Cindi would get crabby Ken would tell her to get in the truck so he could take her to the woods. He knew it always made her feel better to spend time with him outdoors.

Ken accepted Jesus as his Savior in 2007 and was later baptized at Rio Dell Baptist Church by Papa Pastor (Darrow Sanderson). His was a quiet faith, but he loved Jesus and knew he would see many loved ones again in Heaven someday. Ken was also proud of kicking alcohol and an addiction to opiates that he had been prescribed for a back injury.

Ken passed away suddenly at the age of 55 from a massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage on the morning of February 7, 2025. He was preceded in death by his parents, Nancy and Carl Rose, and his special friend, Andy Crase. He is survived by his adoring and devoted wife, Cindi Rose; his children Kenneth Lee Anderson-Rose, Benjamin Rose, Amy Rose, Matthew Rose (Melissa) and Jared Warden; Cindi’s children which he loved like his own, Molly Buck (Felix), Callie Buck, and Levi Buck; his grandchildren, Lauriana, Nevaeh, Braydon, Teheya, Trae, Bellamy, Braxton, Kaliyah, Kaysen, Natalia, and Lily; his siblings David Cowart, Ronald Rose (Heidi), Steven Rose (Audrey), Brian Rose (Tammy), and June Rose-Castro (Noe); and his in-laws, John and Arlene Mock, Aaron Mock (Ruth), and Ammi Mock (Mark). He also leaves behind nieces, nephews, cousins, and friends who mourn his passing.

There will be a memorial service for Ken on Saturday, March 1 at 11 a.m. at Fortuna Church of the Nazarene, 1355 Ross Hill Road, Fortuna. Family welcome you to attend and share your memories of Ken.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Ken Rose’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

(AUDIO) Are You Down to Experiment With Sobriety and Gut Health, Humboldt? The Water Kefiry, a Local Ferment Factory, Would Like to Help You With That

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Feb. 12, 2025 @ 4:44 p.m. / On the Air

Ivy Lucco, founder of The Water Kefiry

(AUDIO) The Water Kefiry on KHUM

How’s your New Year’s resolution going, Humboldt? Maybe you’re one of those people who said, you know, I’d like to cut back on my drinking this year but — ack! — I find myself struggling come the end of the day with that craving to sip on something delightful and delicious.

Well, can we interest you in some water kefir?

These days more and more people are experimenting with sobriety, which is one of the topics discussed on today’s edition of Wellness Wednesday — KHUM’s weekly Lizzerd Kween-hosted discussion of all things health. Today we chat with Ivy Lucco, founder of The Water Kefiry, whose passion is crafting high-quality and innovative probiotic-rich beverages right here in Humboldt County.

Click the audio player above to hear Lucco and Lizzerd Kween chat about the mental and physical benefits of healing your gut and/or click on over to The Water Kefiry website for more information. And be sure to tune into KHUM 104.3/104.7 to hear a new Humboldt-based health enthusiast share their passion on the next edition of Wellness Wednesday.

Ivy Lucco discusses her passion for healthy, fermented foods

Lizzerd Kween, your KHUM Wellness Wednesday host

The KHUM studio in Old Town Eureka | Photos: Andrew Goff