University Police Seeking Suspect Who Allegedly Threw Paint at People on Campus During the Pro-Palestine Protests Monday

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, Oct. 8, 2024 @ 6:47 p.m. / Crime

See photo below. Press release from the Cal Poly Humboldt University Police Department:

The University Police Department (UPD) is seeking the public’s assistance in identifying an individual who is alleged to be involved in assaults at approximately 12:30 p.m., Monday, Oct. 7 at the University Quad at Cal Poly Humboldt.

The incidents, reported by students and a community member, are under investigation. UPD is working to identify the individual, who was last seen wearing a purple hooded sweatshirt, yellow coat, and black pants, and throwing paint from a ladle, according to witnesses.

UPD takes this incident very seriously and is committed to ensuring the safety of the campus and local community.

This investigation is ongoing and anyone with information is encouraged to contact UPD at (707) 826-5555 or submit a tip through the Rave Guardian mobile app. Rave Guardian is available on the Apple Store and the Google Play Store. For more information see this link. Tips can remain anonymous. Your assistance could be crucial in helping us identify the individual responsible.

UPD would like to thank the community in advance for any assistance in this matter.

Suspect.

BOOKED

Yesterday: 5 felonies, 11 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

No current incidents

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Planning Commission Backs Briceland Cannabis Nursery With Zoning Change

RHBB: Humboldt CalFresh Enrollment Surges 55% in a Decade, Outpacing Statewide Trends

RHBB: Six Rivers National Forest Now Hiring

RHBB: City of Arcata Hosting ‘Water Rates Workshop’ February 25, April 15

If You Live in a Problematic Mobile Home in One of Arcata’s Mobile Home Parks, the City May Have Some Money to Help You

Dezmond Remington / Tuesday, Oct. 8, 2024 @ 2:15 p.m. / Housing

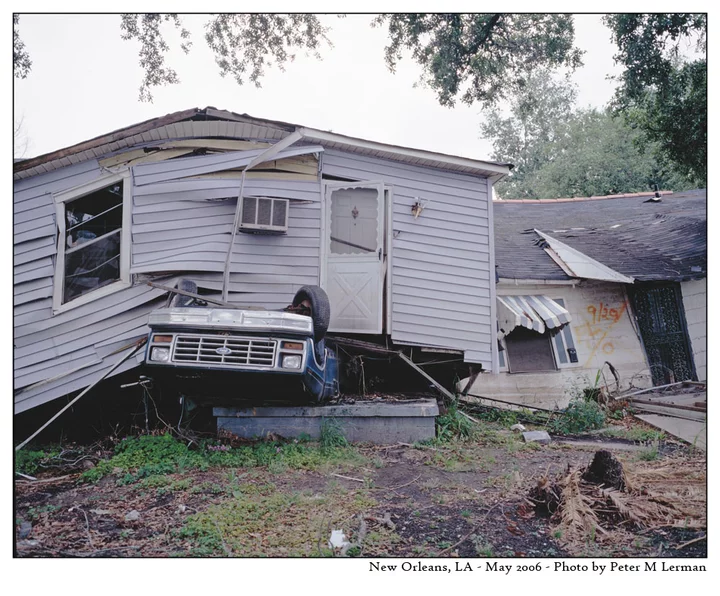

Your mobile home probably doesn’t look like this, but it might feel that way sometimes. Peter Lerman, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Reality, for a few residents in Arcata’s six mobile home parks, is roofs that fail to keep the water out, floors that fail to keep the feet dry, and plumbing that fails to make water go anywhere. Some mobile homes lack infrastructure that would make them accessible to people with mobility issues, or to the elderly.

A new state-funded grant could go a long way towards repairing some of those homes.

The Manufactured Housing Opportunity & Revitalization (MORE) program, funded by the California Department of Housing and Community Development, will grant money to mobile home owners whose homes need repairs. This is the program’s first year, and Arcata received a $3 million award.

To be eligible, people must live in one of the six licensed mobile home parks in Arcata and make less than 80% of the Humboldt County median income.

Applicants whose homes have been cited for HCD code violations are at the top of the list for getting that grant money, followed by applicants whose mobile homes are not up to code but have not been cited yet, and then those with accessibility issues.

Arcata wants people in that second category to ask a contractor to check the damage out and estimate how much it would cost to repair. Arcata is also taking bids from contractors to do the repairs. The program will run until funds run out.

Some of the most common problems with Arcata’s mobile homes are leaky roofs; water-damaged, spongy floors; and plumbing problems. At the Lazy J Ranch, an age-restricted mobile home park for people 55 and older, some homes need ramps or grab bars.

“So we just got a lot of calls, and they’re like, ‘Hey, it’s raining and my roof is leaking, and now I have mold problems,’ or ‘I’m having all kinds of plumbing issues or electric issues,’” Jennifer Dart, Arcata’s Community Development Deputy Director, told the Outpost.

“I think being able to put people in safe and affordable living conditions is going to be huge for the people that can participate in the program. And we want to be able to assist as many people as possible…We’re really excited about the program, and hope to help as many people here in Arcata as possible.”

Instructions on how to apply can be found at this link.

Odd Disturbance in Pine Hill Area Last Night Leads to Police Standoff, Arrest, Sheriff’s Office Says

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, Oct. 8, 2024 @ 10:27 a.m. / Crime

Press release from the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office:

On Oct. 7 at about 6:30 p.m., Humboldt County Sheriff’s deputies responded to a report of a disturbance in the 1100 block of Lloyd St. in the Pine Hill area. The caller reported a male — later identified as Jeffrey Buckalew, age 62 of Fortuna — yelling and banging on their door before leaving the property.

While searching the area for Buckalew, deputies received another report that someone was yelling in a nearby private pasture, about half a mile from the initial incident location. Suspecting that this was the same person, deputies responded to the caller’s residence in the 500 block of Sea Ave. in the Pine Hill area.

Buckalew was found hiding in the pasture’s brush and responded to deputy callouts with threats to use a firearm on them. For safety purposes, deputies drew their department-issued handguns and less-than-lethal weapons, as well as brought a specialized K-9 on scene. Deputies continued to tell Buckalew to cooperate and negotiated with him for over an hour, but he refused to comply with commands and continued threatening the use of his firearm.

After about 90 minutes of negotiating, Buckalew crawled out of the brush with his hands up and no firearm was seen. Shortly after, he fled back into the brush; however, deputies were able to safely apprehend him. Buckalew was taken into custody for disorderly conduct while under the influence (PC 647(f)) and obstructing/resisting an executive officer (PC 69).

This case is still under investigation.

Anyone with information about this case or related criminal activity is encouraged to call the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office at (707) 445-7251 or the Sheriff’s Office Crime Tip line at (707) 268-2539.

GUEST OPINION: To Fix Our County Roads or Not, That is the Question

Steve Madrone / Tuesday, Oct. 8, 2024 @ 7:30 a.m. / Guest Opinion

So the ballots are out, and it’s time to consider many important issues. One issue is in regards to the state of our county roads. I am sure it takes no convincing to recognize the need to repair our roads. They are in horrible condition, and in fact state data show that on average each car owner is spending $900 per year per car on repairs related to bad roads. Shocks, tires and rims, alignments and more from hitting potholes and rough patches. The question is how to raise funds for road repair.

Measure O is on the ballot to raise funds for road repair and a small amount for transit. There are those that have said it should have been a special tax earmarked for roads, but that would have taken 67% of voters to pass. That would have been an unlikely outcome. Polling suggest that a majority will support the measure, but not 67%. So we decided to do it as a General Obligation tax that only needs 50% plus one to pass. Yes, that means that the funds go into the general fund and there is no guarantee that these funds will go to roads. While that is true, the ballot language was crafted carefully to be sure that roads will be the primary use of the funds, with a little to transit. Read the ballot language carefully and you will see that it says 911 emergency response will be improved by fixing roads!

Measure Z was a General Obligation tax as well, and we have made sure that the funds raised did go to improving Public Safety, as promised. Not one dollar went to existing General Fund expenses. We fulfilled our promise to the voters. We hired more deputies and supported local fire departments and have a Measure Z committee to keep all spending accountable. Measure O will also have an accountability committee made up of road experts, labor contractors and members of the public to keep all spending on track. We fulfilled our promise to voters on Measure Z and we will assure these funds from Measure O go to roads and some for transit.

Currently, the limited funds we have for roads goes mostly to emergency repairs, and we have little left to leverage federal and state funding. With Measure O we will generate $24 million dollars per year, and that will allow us to leverage significant federal and state funding. Twenty percent of our funds will leverage 80% federal funding. That means that we could leverage up to $100 million dollars per year with federal and state assistance. That means potholes can be fixed, roadsides mowed to reduce fire starts and visibility increased for cars, bikes and pedestrians. It means taking care of roads before they fall apart and require complete, expensive rebuilds.

Yes, taxes add up, and inflation has hit everyone hard, but this is a small price to pay for greatly improved road conditions. And as mentioned above, we are all already spending the money on expensive car repairs. Let’s move those funds up front and be proactive in repairing roads before they tear our cars apart. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Please consider supporting Measure O as the sensible approach to taking care of our roads. This one cent sales tax is only on taxable items. It does not apply to food, rent, medicines and medical care, and many other items. Thank you for your support.

Steve Madrone

Humboldt County 5th District Supervisor

This California Ballot Measure Promises Money for Health Care. Its Critics Warn It Could Backfire

Kristen Hwang / Tuesday, Oct. 8, 2024 @ 7 a.m. / Sacramento

Much of the California health care industry is united behind Prop. 35, a 2024 California ballot measure that would lock in revenue from a tax on health insurance companies to increase payments to Medi-Cal doctors. Some critics worry it jeopardizes federal funding. Jessica Pons for CalMatters

Among the blitz of election ads flooding TV, social media and street corners, you won’t see any opposition to a ballot measure proposing to lock in billions of dollars to pay doctors more for treating low-income patients.

But opponents of Proposition 35 have a warning even if they don’t have the money to pay for ads: The measure could backfire and cause the state to lose billions in federal funding.

Prop. 35 would take an existing tax on health insurance plans and use the money to increase payment to doctors and other providers who see Medi-Cal patients. Its supporters have raised $50 million, drawing from groups representing hospitals, doctors and insurers.

Medi-Cal, the subsidized insurance plan serving some 14-million Californians, has ballooned in size over the past decade with increased eligibility and benefits. But those changes haven’t come with a commensurate increase in payment to doctors.

As a result, health care providers and advocates say too few doctors accept Medi-Cal, leaving patients with nowhere to turn.

According to the Public Policy Institute of California, the measure is leading and likely to pass.

But opponents, represented by a small coalition of community health advocates, seniors and activists for good governance say the details of the proposition put the state at risk of losing billions in federal funding.

That’s because the federal government under both the Biden and Trump administrations has warned California that its tax on health plans to fund Medi-Cal services takes unfair advantage of a loophole in federal regulations. The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services intends to close that loophole, regulators wrote in a letter to California officials late last year.

“This is the fatal flaw of this initiative,” said Kiran Savage-Sangwan, executive director of the California Pan-Ethnic Health Coalition, which is leading the opposition. “We can all have opinions on how to spend the money, but we have to raise the funds first.”

The problem, opponents say, lies in how California taxes health plans and how Prop. 35 limits changes in the future.

Right now, the Managed Care Organization Tax, also known as the MCO Tax, generates revenue for Medi-Cal by taxing health insurers that serve both Medi-Cal and commercially insured patients. The federal government gives California a dollar-for-dollar match to whatever funds are raised by the tax. For Prop. 35 that’s an estimated $7 billion to $8 billion annually through 2027.

However, California has historically placed the majority of the tax burden on Medi-Cal insurers and not commercial insurers. In its letter to state officials, federal regulators said Medi-Cal plans represent 50% of all insured people but bear “99% of the total tax burden.” That is at odds with the spirit of the law, which is meant to redistribute revenue from commercial insurers to Medi-Cal plans, regulators wrote.

Prop. 35 would cap the tax on commercial insurers at a minimal rate. Any attempts to modify the tax would have to go back to the ballot box or be approved by three-fourths of the Legislature. Opponents say that means federal rule changes requiring the commercial tax to be more equal to the Medi-Cal tax will force the state to reduce taxes on the Medi-Cal plans.

“The end result of that is when the federal government makes good on their promise to change the rules on this tax, the revenue we raise from this tax will be dramatically reduced and we would leave billions of dollars on the table,” Savage-Sangwan said.

Proponents of the measure said this argument is false but did not provide details. They say Prop. 35 will make the Medi-Cal program more stable and higher rates will encourage more providers to see low-income patients.

California’s Medi-Cal reimbursement rates fall in the bottom third compared to all other states, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, and rates for specific services like obstetrics are among the lowest in the country.

“Prop. 35 is a critically needed investment to protect and expand access to care for Medi-Cal patients and all Californians,” said Molly Weedn, spokesperson for the Yes on Prop. 35 campaign, in a statement. “The principal purpose behind Prop. 35 is to provide stability and predictability… to address the significant shortfall of providers who can see Medi-Cal patients.”

The California Association of Health Plans said that it did not ask for the commercial tax cap in the proposition and that it has historically supported this tax structure to pay for Medi-Cal. A higher tax on commercial plans could increase premiums.

Where is Gov. Newsom on Prop. 35?

The largest donors to the yes campaign are the California Hospital Association, Global Medical Response, and the California Medical Association, which collectively donated $38 million. Opponents have raised no money, according to state campaign finance records.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has not taken a formal stance on the measure, although he said at a press conference in July that he’s concerned about how it would lock in tax revenue for a single purpose. The state budget he signed that month shifted most of the tax revenue from the tax on health insurers into the general fund to pay for the Medi-Cal program.

If voters approve Prop. 35, the state would face a $2.6 billion deficit in the current budget, which relies on the tax to fill in gaps. That deficit would increase to $11.9 billion over the next three budget cycles, according to an analysis from the Department of Finance.

“This initiative hamstrings our ability to have the kind of flexibility that’s required at the moment we’re living in. I haven’t come out publicly against it. But I’m implying a point of view. Perhaps you can read between those many, many lines,” Newsom said at the press conference.

Newsom’s office did not respond to multiple requests on whether he would formally oppose the measure.

Savage-Sangwan said the opposition has not solicited any money for their campaign.

“We are using the very small megaphone that we do have to just get the facts out,” she said.

Trade-offs in 2024 health care ballot measure

The political split over Prop. 35 is unusual. The measure’s opponents are often on the same side as its supporters when it comes to health policy issues in the Capitol. But community health advocates say they’re speaking up because the future ramifications of the initiative are too risky.

“We want to make clear that the goals of the prop are goals we agree with. We recognize our providers in Medi-Cal are paid far too little and that disproportionately impacts people of color, children of color especially,” said Mayra Alvarez, president of The Children’s Partnership, another opposing group.

Some lawmakers agree. During multiple budget hearings, Sen. Caroline Menjivar, a Democrat from Van Nuys, came to oppose the proposition in part because the industry organizations that negotiated who would get money from the tax left out “community providers” and those “who don’t have high-paid lobbyists.”

“By listening to those with boots on the ground, the legislature developed a plan to equitably address many Medi-Cal concerns over the next few years,” Menjivar said in a statement from the opposition campaign.

The tax is expected to generate more than $30 billion over the next four years. The budget Newsom signed puts most of the money in the state’s general spending account, but set aside roughly $2 billion to increase rates for services including community health workers, private duty nursing, adult and children’s day centers and children at risk of automatic Medi-Cal disenrollment. If Prop. 35 passes, different groups will get rate increases.

Weedn with the Yes on Prop. 35 campaign said the initiative won’t automatically cause cuts if it passes. It would be up to the Legislature to decide how to pay for the programs opponents are worried about, she said, and that the initiative provides about $2 billion of flexible dollars annually for legislative priorities.

###

Supported by the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF), which works to ensure that people have access to the care they need, when they need it, at a price they can afford. Visit www.chcf.org to learn more.

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

OBITUARY: Aleta Joyce Hutcheson, 1953-2024

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, Oct. 8, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Aleta Joyce Hutcheson, born in Willits, aged 71, passed away

peacefully at her home in Eureka on October 3, 2024. Her selflessness

and generosity were evident in every aspect of her life. Born on July

31, 1953. Aleta dedicated her life to her family and friends. She

always prioritized their needs above her desires, even giving up a

planned career in the military that she so much wanted. Instead, she

dedicated her life to taking care of her family and devoted many

years to community service.

Aleta spent most of her career as a dedicated worker for Rite Aid. She was, for decades, an enthusiastic fundraiser for various charities. A lover of reading and movies, Aleta viewed these hobbies as windows to the world she longed to explore. Additionally, she cherished collecting charming lapel pins and other small decorative items, each item holding a special place in her heart. She was also a artist loved to draw, She loved animals.

She attended Leggett Valley Primary School and graduated from Eureka High School, laying the groundwork for her lifelong commitment to community service. Though she did not pursue higher education, her impact on those around her was profound and far-reaching.

Aleta is survived by her beloved brother, Dwain A. Hutcheson, who resides in Baltimore MD. She was preceded in death by her dearly loved mother, Frances L. Hutcheson, and cherished brother, Timothy Hutcheson, and father, Edgar Elton Hutcheson. Her family finds solace in believing that she is now at peace and reunited with her loved ones.

Aleta’s life was a testament to the power of selflessness and caring. She will be deeply missed by all who knew her, leaving behind memories filled with love and selflessness.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Aleta Hutcheson’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

Scary House Fire on McK’s Second Road Stomped Out Quick With Minimal Damage, Arcata Fire District Says

LoCO Staff / Monday, Oct. 7, 2024 @ 2:16 p.m. / Fire

Press release from the Arcata Fire District:

On October 6, 2024, at 3:33 P.M. units from Arcata Fire District, Fieldbrook Fire, Cal Fire and Blue Lake Fire were dispatched to a reported structure fire on the 2100 Block of Second Road in McKinleyville.

As units responded from their stations they could see a large column of black smoke from miles away. The first arriving engine reported two outbuildings on fire with fire spreading to a single- family residence and the surrounding vegetation. The engine attacked the fire extinguishing the fire on the residence and surrounding vegetation to prevent further spread. Additional, units arrived and attacked the fire in the two outbuildings. Personnel had the fire controlled in ten minutes. Arcata Fire personnel confirmed nobody was injured from the fire. Arcata Fire personnel remained on scene for about two hours extinguishing hot spots and conducting an investigation. Allied fire agencies covered the Arcata Fire District area during the incident.

The cause of the fire is undetermined but may have been from a faulty electrical strip plug. Damage estimates to the two outbuildings, house, and belongings is estimated at $10,000. Arcata Fire wants to encourage people to dispose of damaged strip plugs and extension cords.

If you have any questions, please contact the Arcata Fire District at 707-825-2000.

Photos: Arcata Fire District.