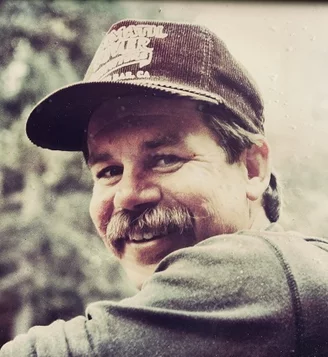

OBITUARY: Michael Duane Bode, 1948-2024

LoCO Staff / Saturday, July 13, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Michael Duane Bode

May 19, 1948 - June 26, 2024

Mike, known to his grandchildren as “Papa Mike,” left us on June 26, 2024 to go home, to his father in heaven. As his family and friends feel the enormous void he leaves behind with his passing, we are also filled with hearts of gratitude for the loving husband, father, grandfather, cousin, in-law, uncle and friend he was to so many.

Mike was born in Los Angeles in 1948 to Melvin and Barbara Bode. They eventually settled in Eureka when he was young. They were blessed with two more boys, Rob and Chris Bode. Mel was a draftsman in the building trades. Extraordinarily, all three Bode brothers went on to be building contractors in the Humboldt County area, some for over 50 years.

Mike attended Marshall Elementary School, Jacobs Junior High School and Eureka High School. ‘Bode’ was an outstanding athlete at EHS, where he excelled at playing football and track and field events. His creativity began to emerge during this time as well, when he discovered a love of painting, pottery and building. After high school he was drafted into the U.S. Army and was sent overseas to Vietnam. He served bravely, like so many of his comrades, and completed two and a half years and left a sergeant.

He returned home to his family where he went onto attend College of the Redwoods, where he received his A.A. and played defensive end on the 1969 undefeated CR Football team. During this time, he began to date Audrey Watson, who was the love of his life and partner in everything. They were married in 1971 and have been married for 52 years.

He went onto attend Humboldt State University, where he received a bachelor degree in industrial technology and started Bode Construction Company in 1974. One of his first construction projects was building his own houseboat with his dad on Trinity Lake. Mike built many buildings and used his drafting skills to build throughout Humboldt County, where he made many friends and connections that still are felt by his family, friends and community today. His creativity and strong work ethic enabled him to build a foundation that he graciously shared with everyone around him.

In 1972, he took on a new role as a dad when he welcomed his little girl Stephanie. He was always devoted, supportive and hardworking when it came to her and his entire family. He would spend countless hours teaching his kids and grandkids to carve a turkey or build something from nothing, a big lap to sit on or how to pick a garden. He was so many things to so many people. In 1974, he welcomed his son Ryan. Mike and Ryan enjoyed the outdoors snow-skiing, houseboating on Trinity Lake and a love of working with your hands. Mike taught Ryan to build. He passed on his creativity, eye for detail, exceptional work ethic and toughness that only those in the construction trades will understand. They ran Bode Construction Company together beginning in 2001, and Mike continued to stay active in the business up until his passing. He loved to work and enjoyed sharing his gifts for building.

In 2003, he began another new role as grandpa, and was aka “Papa Mike.” Papa Mike pulled out all the stops for his five grandsons and two granddaughters. Papa Mike and Nana lovingly put their valuable time, energy and resources into these kiddos who made them laugh and love the world in only ways that grandkids can. Papa Mike would spend countless hours watching his athleticism on display through his grandkids on the football field, baseball diamond, soccer field, basketball gym, rodeo grounds, gymnastics meets and any and all school functions. He loved supporting athletics and loved competition and the grit it took to do it.

To really know Mike you had to know his hobbies. He was passionate about so many things over the years. In the beginning, he loved to paint and do pottery. He loved to snow-ski in the winter and spent many hours on his houseboat in the summer. Always a bit of a prankster at the houseboat, his nieces and nephews always had to keep one eye on what they were doing and the other on where Uncle Mike was.

Mike had a great passion for aviation. His dad Melvin was a pilot in WWII flying the P-61 over the Pacific and Mike seemed to be drawn to the heavens as his dad was. He bought his first plane in 1989 and then later upgraded to a plane that was known to buzz the skies of his home near the air strip at Murray Field. Later he picked up fly fishing, riding his bike, gardening and wine making. He loved to have his family and friends together in all of these activities. He and Audrey created an oasis at their cabin in Willow Creek with a garden that was extraordinary. He loved their garden and during the harvest months you didn’t leave his presence without taking home delicious fruits and veggies for you and your family. He loved to bottle wine with anyone who wanted to show up and bottle, cork, label, etc. and it didn’t matter how old you were. Elbow grease was the main ingredient. Later the wine would be enjoyed and shared with his family, friends and community.

Mike, together with Audrey, made exceptional memories filled with a lifetime of love and laughter. They worked together running their construction and rental businesses, raised kids, loved on grandkids and traveled many parts of world together. Their travels whether they were near or far were always together where they would take in the sites and would appreciate the time they were given.

He is preceded in death by his father Melvin Bode, his mother Barbara Bode-Morse, his brother Rob Bode, father-in-law William Watson Jr., and mother-in-law Edith Watson. He will be lovingly remembered by his wife Audrey Bode, daughter Stephanie Schneider (Travis), son Ryan Bode (Melissa), grandkids Hayden, Rogan, Macy, Riley, Parker, Alayna and Cade, his brother Chris Bode (Denise), sister-in-law Kay Bode, cousins, in-laws, nieces, nephews and countless great friends.

Mike was a big personality and a generous spirit who enjoyed life and was grateful for all of its harvest. There will be a celebration of his life on Saturday, July 27 at The Faith Center located at 1032 Bay Street, Eureka from 11 a.m.-12 p.m., followed by a gathering immediately after at Old Growth Cellars located at 1945 Hilfiker Ln, Eureka until 3 p.m. In lieu of flowers, please consider donating to a charity of your choice in his name.

We will miss you, rest in eternal peace Papa Mike.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Mike Bode’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.

BOOKED

Today: 4 felonies, 7 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

3455 Redwood Dr (HM office): Trfc Collision-1141 Enrt

3220-3529 Samoa Rd (HM office): Trfc Collision-Unkn Inj

1901 Mm101 N Hum R19.00 (HM office): Trfc Collision-Minor Inj

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Major Roadwork Scheduled Friday, Feb. 27, through Thursday, Mar. 5

RHBB: Spyrock Road Closed After Grenade Found in Abandoned Vehicle; Bomb Squad Requested

Fishing the North Coast : Sacramento, Klamath salmon rebound projected for 2026

OBITUARY: Michael John Watson, 1952-2024

LoCO Staff / Saturday, July 13, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Michael John Watson was born in Riverside, California, at the Air Force base on September 29, 1952. His father had just served a tour of duty in Korea and the Korean war was just coming to an end. They moved to San Francisco soon after Michael’s birth and they all enjoyed living in San Francisco. His father became an accountant for Standard Oil and his mother became a clerk at UCSF Hospital. Michael started elementary school in his neighborhood of Twin Peaks and went on to become lifelong friends with Ricky Montalvan and Larry Cressey, two chums that he met before high school. One of whom he met in elementary school, and the other one he met in junior high school. He also had a high school chum who was also a friend for life, named David Subke.

While he was still in San Francisco he had a paper route delivering the San Francisco Chronicle. He loved reading the sports section of the Chronicle all his life, as he was very faithful to two sports teams that he “grew up with”, the San Francisco Giants and the 49ers. Later, he became a fan of the Golden State Warriors as well. He would always fly their flag on his truck during the playoffs.

Also, while he lived in SF, Michael earned his nickname. He started surfing at a fairly young age (Jr. High) down at the beach near the San Francisco zoo. He went with some surfing buddies and it wasn’t long before they started calling him “The Walrus” because of his ability to withstand cold water. Eventually, by his high school years, that name was stretched to “Wally the Walrus” , and that has been who he was ever since.

He played the trumpet in the school band in elementary, jr. high school, and into high school. He attended Lowell High School, SFs finest high school, especially for musicians. During his Senior year at Lowell High School, he went to Japan with the Lowell High School Orchestra. They were all great musicians, and they played all over Japan. Wally always said his claim to fame were his performances in Japan. The Japanese people truly loved these high school virtuosos’ talent in music. Later on, his interest in music would continue, and he practiced and played his horn for over 20 years. In the town of Somes Bar, CA, he played in a band with Tina Marier’s River Bar Community Band. It was with this little group that Wally helped to premiere a piece of music written especially for them. It was called the Klamath River Suite, composed by David Subke, Wally’s high school chum who had joined the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra and he also became a composer.

When he was nineteen he came up to Forks of Salmon with his buddy, Rick Montalvan, to visit Larry Cressey, who had apprenticed with an old mountain man and gold miner named Manuel “Mike” DeFaria. Mike taught them all just about everything a person would need to know to become self-sufficient in the mountains. Although Wally’s dad took him hunting and fishing as a boy and he already knew a bit about guns and hunting. Mike taught him how to hunt bear, elk, deer and game birds grouse and turkeys. He learned how to render bear fat and how to waterproof his shoes with it…. he also learned a lot about creating gravity water systems and gardening his own vegetables. He mastered all of this well before his death. After this visit to Forks of Salmon, he never moved back to SF. He lived at a place called the Hansen Mine, located 1 mile up from the forks of Know Nothing Creek which is close to where his wife first met him at Forks of Salmon. Know Nothing Creek is a tributary of the Salmon River. Edna and her son Ricky became close neighbors to him in February of 1974. And by summer of that year, they were all living together in a little cabin at the forks of Know Nothing Creek. Wally and Edna had their son Woody by November of 1975, at the same little cabin and you could say they lived happily ever after. Wally and Edna loved life in the mountains and never wanted to live anywhere else.

Wally was always an avid fisherman. In 1974 he started working in Somes Bar for the Throgmorton family as a guide for the Somes Bar Lodge. He also was a logger for a couple of years as well as a tree planter for ENT forestry. Not before long he became a partner with Jody Pullen, in what would become his own business, Klamath River Outfitters. Initially he specialized as a top steelhead fishing guide. Later in 1983, the family moved to Somes Bar, where they all could still pursue their dreams of mountain living and where Wally practiced his expertise of carpentry and built their beautiful family home. This is where Wally lived out the rest of his life.

Wally pioneered Wing rafts on the Salmon River. He was also one of the first people to go commercial rafting on the Salmon. For the next fifty years he fished and rafted the Salmon and Klamath Rivers faithfully as a top guide. His wife Edna taught for thirty-two years at Junction Elementary School, first as the upper grade teacher for 19 years and then as a special education teacher for the county of Siskiyou, and her route included Junction School in Somes Bar. Wally also stayed busy at Junction School, where he became a Little League Coach for almost 20 years, joined by Toz Soto and Brandon Tripp. Wally loved coaching baseball, and one of the proudest moments of his life was when his team, the Somes Bar Cougars, won a trophy for being undefeated the whole season. Wally also loved taking kids rafting. Throughout his life it is likely he took most of the kids in Somes Bar rafting.

Wally died on May 22, 2024, from a horrible brain tumor called a Glioblastoma, that had only been diagnosed about 10 days prior to his death. Luckily for Wally, his death was peaceful and painfree, and he was surrounded by his wife and other loved ones.

Wally was predeceased by his mother, Patricia Watson, his father Jerry Albert Watson, all his grandparents, paternal, Albert and Jennifer Watson, maternal, John Murphy and Norine Guerin Murphy, and his brother, Tim Watson, who was 24 when he died on Know Nothing Creek Road in 1983. Sadly, Woody predeceased Wally in May of 2020. Wally was also predeceased by his 1st cousin, Cherolee Slinger and her parents, his aunt and uncle, Chet and Evaline Slinger. He was also predeceased by his good friends, Wayne Glascoe, Dave Subke, Les Harling, and Lloyd Ingle. Wally is survived by his loving wife, Edna Watson and her-son, Rick Glascoe, and Rick’s four children, Brandi Grimm and son Dylan, Angelica Hokanson and husband Mitch and their two children Hudson and Cash, Buck Wayne Glascoe age 18, and then Rick’s youngest daughter Eva May Glascoe age 16. Wally is also survived by Woody’s children; Tim Watson, age 21, Virusur Watson, age 20 and Patty Watson, age 12, and their mother, Alicia Whitman and her other children, Layla Aubrey, age 10, and Layla’s brother and sister Laina and Joaquin both age 14, as well as Luis Osario, age 18. Wally is also survived by many friends, who over the years have been like extended family.

HE WILL BE GREATLY MISSED BY MANY. “White Water Wally the Walrus, you are Boat Man Extraordinaire!” There will be a Celebration of Life Memorial service for Wally, to be held at Ti Bar Campground in Somes Bar, on Sunday, July 21, 2024 starting at noon. Everyone is welcome. Look for local flyers or on Facebook for more info, or call Edna. It is a potluck.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Michael Watson’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.

Last Night Was Another Busy Night for Arcata Fire, as Our Heroes Responded to a Car Crash and a Lumber Mill Fire Practically Simultaneously

LoCO Staff / Friday, July 12, 2024 @ 10:13 a.m. / Emergencies

Press releases from the Arcata Fire District:

Incident one:

Captain Freeman at the vehicle after extrication. Photo by Asst. Chief McDonald.

On Thursday, July 11 at 10:27 P.M. the Arcata Fire District was dispatched to a traffic collision on the Northbound side of Highway 101 at Airport Road.

The incident was reported as a ‘single vehicle off of the roadway.’

First responding units stated extrication was needed. All three of AFD’s engines arrived on scene and proceeded to remove the driver’s side of the vehicle with extrication equipment in order to remove the patient from the vehicle.

Care of the patient was then transferred to Arcata/Mad River Ambulance.

Fieldbrook Volunteer Fire was dispatched to a medical aid in AFD’s response area during the time when all of Arcata’s units were involved in the extrication.

All of Arcata’s units were released by CHP to respond to a commercial structure fire that was dispatched in Arcata.

Incident two:

Photo by Arcata Fire PIO Alyssa Alvarez.

On Thursday, July 11 while at a vehicle extrication on HWY 101 in McKinleyville at 10:59 P.M. the Arcata Fire District was dispatched to a commercial structure fire at a lumber mill at the 3700 block of West End Rd.

First arriving units from AFD arrived to find a two-story warehouse type structure with heavy fire on an exterior wall and roof of the building.

Upon entering the building, firefighters found fire was spreading in the interior which housed industrial equipment and lumber. Firefighters attacked the fire, knocking down the main body of fire within fifteen minutes.

Mutual aid agencies continued to respond and assisted at the scene as well as provided coverage for Arcata’s District.

The Arcata Volunteer Logistics Unit was on scene to provide relief and rehab for firefighters.

The cause of the fire is under investigation.

Arcata Fire would like to extend our sincere thanks to our mutual aid partners Fieldbrook Fire, Samoa Fire, Humboldt Bay Fire, Blue Lake Fire, Westhaven Fire, Arcata Police and PG&E. We would also like to thank CaFire ECC for coordination of coverage of our district.

OBITUARY: Judith Mae Hagood, 1941-2024

LoCO Staff / Friday, July 12, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Judith

Mae Hagood passed away on July 3, 2024, in Merced. Judith was born on

October 6, 1941, to James and Zelma Franzoni. Judith was the oldest

of two daughters born to James and Zelma. Judith was preceded in

death by her youngest sister Sharon K Franzoni, who died on September

1, 2010.

Judith was raised in Big Lagoon, where she attended elementary school. She went on to attend Arcata High School and then junior college in Redding at Shasta College. In 1964 Judith married James Hagood and moved to Orick. She and Jim would eventually buy Hagood’s Hardware from Jim’s parent Lowell and Jean Hagood. Judith would then dedicate her life to running the hardware store for the rest of her life.

While running the hardware store Judith became a member of the Orick Volunteer Fire Department. She would spend the next 54 years being a member of the OVFD. Her involvement in the Fire Department brought her great pleasure. Caring for and assisting others was a great passion of hers. Judy dedicated her adult life to providing care to the community or Orick. As many citizens of Orick grew older, Judy was the one that would check on them daily and help with their medical needs.

For a long period of time Judy was active in the Camp Fire Girls program. Many young girls in Orick were members of the Camp Fire Girls and attended meetings at the hardware store where Judy mentored them and prepared them for planned activities. These activities included fund raisers and cheerleading competitions.

In addition to Camp Fire Girls’ activities, Hagood’s Hardware was also a place where Judy would serve as a babysitter for many of the young children of the Orick Community. Judy was trusted by a great deal of parents to babysit their children while they worked, shopped, attended meetings, etc. Generations of children spent time in Hagood’s Hardware while Judy looked over them.

Judith leaves behind her husband Jim of 59 years. In addition, she leaves behind her son Michael Hagood and his wife Leticia Hagood as well as their two sons Brendan Hagood and Darren Hagood. She also leaves behind her daughter Betsey Paulo and her husband Doug Paulo along with their two daughters Kimberly Paulo and Paige Paulo.

A memorial for Judith will be arranged for a later time.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Judy Hagood’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.

OBITUARY: Douglas Alan James, 1965-2024

LoCO Staff / Friday, July 12, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Douglas Alan James, born December 10, 1965, passed away on July 3, 2024, surrounded by his family in Eureka.

Douglas, born #10 into a large family, was the baby. He would always say, “Mom was saving the best for last.”

He is survived by his brother Darrell “Joe” Sherman; sisters Diane “Susie” Wilson, Alzada “Sandy” Duncan; children, Aaron Bennett, Corey Cole, Teresa McGinnis, Angela King, Isabella James, Angeleah James, Carol Lowe; grandchildren, Donovan Bennett, Shaya Robinson, Kiara McGinnis, Mikaela James-Wheeler, Chayce McGinnis, Shane James, Jeremy Houston Jr., Rachel Houston, Volinda Houston, Isaiah James, Octavia Lowe; great-grandchildren, Nora Bennett, Haley Bennett, Annika Bennett. He is also survived by numerous cousins, nieces, nephews and friends, too many to name.

He is preceded in death by his mother, Beverly Jean James (Moorehead); fathers, Melvin “Red” James Sr., Cecil “Smokey” Sherman Sr.; brothers Duane “Pete” Sherman, Robert Sherman, Dennis Sherman Sr., Cecil “Sharky” Sherman Jr., Melvin “YoYo” James Jr.; sisters Diane Sherman, Shirley Sherman, Donna Sherman, Pamela James, Patty James; nieces Stacy Lynn Sherman, Debra Albers (Sherman); great-nephew Alex Lopez.

Douglas, an avid Raiders fan, enjoyed going to their games and collecting Raiders memorabilia, including several Raiders and Raiderettes tattoos. He would always bet his money on the Raiders, no matter the season. His loyalty was impeccable. A true RAIDER 4 LIFE. For this reason, Douglas’ children would like to ask that you wear something with the Raiders team logo or their colors, silver and black

Douglas, a Wiyot Tribal Member, grew up on the Table Bluff Rez in Loleta and the Tolowa Rez in Smith River. He attended Loleta Elementary School and Fortuna Union High School.

Douglas held several different jobs, including bucking hay, fisheries, Fidgelands potatoes, Stanhurst Bulb Farm and as a comedian.

Douglas had a great sense of humor. He was always laughing and joking, making people laugh. He also had a big heart and always had his door open for anyone who needed help, a place to stay, something to eat, and, back in the day, a place to party, drink, listen to music, and play games: cards, dice, dominoes, darts, horseshoes. He played them all “victoriously!” Beating him rarely happened.

All are welcome and invited to come and share Douglas’ celebration of life beginning on July 13, 2024. His graveside services will be held at 1 p.m. in the Sunset Memorial Park, located at 3975 Broadway, Eureka. This will be followed by Douglas’ celebration of life potluck held at Bear River Tish Non Community Center, located at 266 Keisner Road, Loleta. Come share your stories and memories of Douglas with us.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Douglas James’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.

Cal Poly Humboldt President Tom Jackson, Jr. to ‘Step Away’ Next Month But Remain at University

LoCO Staff / Thursday, July 11, 2024 @ 12:15 p.m. / Cal Poly Humboldt

Jackson. | Photo via Cal Poly Humboldt.

###

From Cal Poly Humboldt:

Cal Poly Humboldt President Tom Jackson, Jr. will be stepping away from his current position next month. His departure caps a five-year tenure that saw a dramatic re-shaping of the University, including new academic programs and a historic state investment of new funding as part of the change to a polytechnic.

President Jackson informed CSU Chancellor Mildred García and colleagues of his decision earlier today. He has been consulting with the CSU Chancellor’s Office to ensure an orderly transition since early spring semester. An Interim President will be appointed shortly, and the CSU will carry out a national search for President Jackson’s replacement within the next year.

“Cal Poly Humboldt is an amazing place with special people. I have had the privilege to work alongside scientists and future scientists, teachers and future teachers, artists and future artists, engineers and future engineers, and leaders and future leaders. Like many of you, I wake up every day and remember what a gift I have been given: to have the opportunity to inspire and lead others. Your work makes a positive difference for our students. Please never forget that,” says Jackson.

President Jackson plans to transition into an ongoing role at Cal Poly Humboldt, retreating to his tenured professorship working with the College of Professional Studies and the College of Extended Education & Global Engagement.

President Jackson has had a career in higher education spanning nearly 40 years, the last decade as President of Cal Poly Humboldt and, prior to that, Black Hills State University in South Dakota. He served 18 years as both a Dean and a Vice President at a number of institutions.

From the beginning of his time at Humboldt, President Jackson encouraged the University to raise its sights, to innovate and lead, to find the good in people, and to always focus on providing a positive and meaningful educational experience for students, including improving the residential experiences for students moving to the North Coast.His visionary leadership resulted in one of the most significant transformative efforts in the institution’s history. The conversion to a polytechnic, along with the historic state investment of $458 million to help bring the plans to reality, will have a positive impact on the campus and community for generations to come. Within just a few years, Cal Poly Humboldt has added nine new bachelor’s degrees and a new master’s degree, and is building a new residence hall project that will house nearly 1,000 students. Construction is poised to begin on a new Engineering & Technology Building, which will be the signature new academic facility of the polytechnic effort. Polytechnic funding and other efforts have also supported acquisition of new properties, a state-of-the art replacement for the Coral Sea research vessel, and updates to campus labs. Additional new academic programs will be added over the next six years, including those in the engineering and health care fields. A new facility to support sustainability efforts and additional campus housing are also in the works.

President Jackson has led a significant expansion of outreach by the University including a new brand that showcases academic excellence and opportunities for student engagement. He has led growth in important funding in support of students. This has included a doubling of the amount of research grants and contracts to more than $67 million annually, one of the highest in the 23-campus CSU system. The University has also seen record levels of support from alumni and others. It recently completed its first comprehensive fundraising campaign, Boldly Rising, with more than 10,000 donors giving well over the campaign goal of $50 million to support scholarships, academic programs, and other campus priorities.

Budget and enrollment have been a focus throughout President Jackson’s tenure, as the University had experienced a number of years of declining enrollment and resources. The campus successfully balanced budgets after climbing out of a substantial $25 million deficit. Overall enrollment has turned around, and is about to enter its third straight year of growth, even as many campuses throughout the nation struggle with declines. Overall applications by new students have reached record levels. In addition, a variety of efforts have led to more students staying in school and strong increases in graduation rates.

Community outreach and engagement has been a major priority for President Jackson. He has built trust and launched partnerships with the region’s Tribal Nations, which he cites as “generational work” and among his most important successes. He has also worked closely with President Keith Flamer and the College of the Redwoods to forge a model relationship between a two-year and a four-year institution. Both President Jackson and President Flamer are proud military veterans and have strongly supported veteran students.

President Jackson spent significant time and energy with outreach to regional government leaders at all levels as well as community organizations, including Chambers of Commerce. He has involved the University in important community development efforts, including wind power and the undersea high-speed internet cable–with a focus on educational needs, grants, and partnerships. In all of these community efforts, the goal was to engage individuals across campus in order to build deeper and broader connections.

An area of emphasis throughout President Jackson’s career has been international education. He believes international competency will someday be considered as important as digital competency for college graduates, and frequently speaks of Humboldt’s potential for creating a “model global community.” Successes in this area include implementing the International Service Learning Program, with offerings in both the Philippines and Mexico. In addition, the University recently signed an expansive new agreement to cooperate on research and more with Charles Darwin University in Australia, Blue Lake Rancheria, and College of the Redwoods. Cal Poly Humboldt will continue its international engagement with Cebu Technological University and Cebu Normal University, both located in the Philippines.

Among the new programs launched in the last five years was a first-of-its-kind bachelor’s degree program at Pelican Bay State Prison, which is a partnership with College of the Redwoods and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. President Jackson oversaw the launch of Fall commencement ceremonies so that more students and families would have a chance to participate in the important rite of passage, and then went a step further and added a regional commencement ceremony in the Los Angeles area. As a result of many efforts in facilities, academics, research and more, Cal Poly Humboldt achieved its highest ever rating on STARS (The Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System), which is used by hundreds of colleges and universities nationwide to measure their sustainability efforts. Humboldt’s Gold rating and overall score is the second highest among CSU campuses.

There have also been many successes within Athletics, an important area to President Jackson, who himself was a student athlete. He was known to seek input from the Student Athletic Advisory Committee, who often had highly balanced and engaged students representing the first-year to graduate levels. During his tenure, the Athletics program earned two national championships in Men’s Rugby and Women’s Rowing, improved academic performance, and added additional sports, including men’s wrestling and men’s and women’s rodeo. He sought out opportunities to know the student-athletes and their parents. His goal was to travel to at least one away event per team, per season, to spend time with students and their families.

President Jackson led Cal Poly Humboldt through a number of crises. Very shortly after he began, there were two multi-day power outages, followed closely by the Covid pandemic which struck halfway through his first year. Rather than retrench, he encouraged the campus to continue pursuing its aspirations and to prepare for opportunities to grow and support the region.

Over the past five years, President Flamer and President Jackson have shared the biweekly Times-Standard column College Matters. They have authored more than 100 articles each. The two presidents have also shared a KHSU talk radio show called, “Talk Humboldt with Keith and Tom.” Together they have interviewed dozens of local business and community leaders on subjects related to the North Coast. These were strategies used to share important information with the community.

Leading the campus during these transformational times has been the pinnacle of President Jackson’s long career in higher education. Even so, he has remained steadfast in his commitment to his family, balancing the heavy demands of leadership with time and attention given to his surviving daughter and spouse. The Jacksons lost their 22-year old son in a car accident in 2020.

In a letter to CSU Chancellor García outlining his plans, President Jackson highlighted the transformation underway on campus as well as some of the personal reasons guiding his decision. “As a President within the CSU, I have had 22 other close colleagues that matter greatly. Working beside them has helped this campus immensely when needed most.”

“I am a dad at heart,” he wrote. “I come to work every day to provide for my family while trying to make a difference in the lives of others. It was the desire to serve and help others that led me to this profession. Today, I find great joy in being the passenger in a small plane that my daughter is piloting. It was almost 22 years ago that I was the one flying and she was the nine-month-old sleeping beside me in the plane’s cabin.”

“We do the very best we can every day, trusting the faculty, staff, and students to do the same,” Jackson says. “In the end, it remains about the students. And what has been most rewarding are the many students who have graduated over the last five years. Nothing replaces the smiles of a student and the applause and excitement from their family as their student crosses the stage to receive their diploma. That is what it is all about.”

Statement from California State University Chancellor Mildred García

Eureka City Schools and AMG Communities Delay the Close of Escrow on Jacobs Campus Yet Again

Ryan Burns / Thursday, July 11, 2024 @ 11:44 a.m. / Education , Housing

The former Jacobs Middle School campus at 674 Allard Avenue in Eureka. | File photo.

###

Today was supposed to be the day that Eureka City Schools finalized a deal with the shadowy corporation AMG Communities - Jacobs, LLC, to swap the district’s former Jacobs Middle School campus for a small residential property at 3553 I Street in Eureka plus $5.35 million — a “land exchange” agreement valued at $6 million.

But at a special meeting last night, the district’s Board of Trustees approved a second amendment to the agreement, extending escrow until next month.

“The District is working with our surveyor to finalize the remaining details and plans to submit documents to the City of Eureka sometime next week, with a close of escrow by our next regularly scheduled Board meeting on August 8th,” the district’s executive assistant in the superintendent’s office, Micalyn Harris, told the Outpost in an email.

This represents the third delay in closing the deal following an initial feasibility period that was mutually extended to Feb. 26 and then an amended agreement approved by the board back in April. It has now been nearly seven months since the surprise announcement of the deal at a Dec. 14, 2023, board meeting.

According to the agenda for last night’s meeting, this second extension is necessary “to allow the Developer to cure certain conditions at 3553 I Street which were raised by the District, and to allow the District to complete the surveying and subdivision process to facilitate the conveyance of the Jacobs site.”

As noted in previous reporting, the interests behind AMG Communities have repeatedly refused to identify themselves except to insist that Security National founder Rob Arkley is not among them.

A website established by the company says it is backed by “a small investment firm that holds interests in real estate and businesses,” though a spokesperson told the North Coast Journal back in January that the company is “a private group of small individual and family investors focused on the single purpose for which it was formed — acquiring the former Jacobs Middle School site.”

While AMG Communities has provided the district with a $100,000 deposit, the text of the agreement says that this money “shall promptly” be returned if the deal doesn’t close by Aug. 9, unless both parties agree in writing to extend escrow yet again. (A $35,000 deposit that AMG put down on the I Street property is non-refundable.)

AMG Communities says on its website that while the 8.6-acre Jacobs property “is large enough to support a mix of housing and some neighborhood-serving commercial uses,” it also acknowledges that no “firm plans” have been developed yet.

The City of Eureka has several multi-story housing projects in various stages of development as part of a years-long plan to convert underused municipal parking lots into affordable apartments. Security National, meanwhile, is financing both a political group (Citizens for a Better Eureka) and a ballot measure (the “Housing for All and Downtown Vitality Initiative”) aimed at stymying those developments and preserving the downtown parking lots.

###

PREVIOUSLY:

- Who Will Get the Former Jacobs Campus? Bidders for Blighted Site in Highland Park Are the City of Eureka and the California Highway Patrol, With a Decision Coming Soon

- The CHP Would Like to Build New Headquarters on the Property Championed by People Opposing Downtown Housing Development, and There Was a Meeting About it Yesterday

- Open Letter Urging Eureka Voters Not to Sign the ‘Housing For All’ Petition Endorsed by 100+ Humboldt County Residents, Including Local Leaders in Politics, Business and Culture

- New Coalition — ‘I Like Eureka Housing!’ — Formed to Oppose Arkley-Backed Pro-Parking Lot Initiative

- Mystery Item on Tonight’s Eureka City School Agenda Suggests Imminent Action on Jacobs Campus, but the School District Won’t Share Details

- Eureka City Schools Board of Trustees Unanimously Votes for So-Called ‘Land Exchange’ With Mystery Developer

- The Eureka City Schools Board Voted on a Resolution Last Week That Was Not Published Before the Meeting. Is That Legal?

- At Town Hall Meeting, Frustrated Residents Discuss Future Development of Eureka’s Jacobs Campus; Mystery Developer Still Mysterious

- Security National Has Spent at Least $236,000 on the Pro-Parking ‘Housing for All’ Initiative So Far

- Grand Jury Slams Eureka City Schools For ‘Secretive’ Jacobs Campus Deal

- League of Women Voters Chimes in on Lack of Transparency in Eureka City Schools Property Transfer

- Rob Arkley Pursued Purchase of Jacobs Middle School Property Before Eureka City Schools Entered Land-Swap Deal With Secretive Corporation