OBITUARY: RoseAnn Cooney, 1937-2026

LoCO Staff / Today @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

RoseAnn Cooney

Dec. 21, 1937 - Jan. 29, 2026

RoseAnn Cooney passed away peacefully at her home on January 29, 2026. She was born December 21, 1937, to William “Bill” Quilici and Lena Quilici. At the age of four, RoseAnn’s father and brother passed away unexpectedly.

Lena met and married Louis Legaz in 1945. RoseAnn gained a baby sister Angie in 1950 and a baby brother Mike in 1955. When RoseAnn was 17 years old she married Lynn Rieke. Together they had four boys – Kenny, Ronnie, Jack and Lynn Jr. While raising the boys on Humboldt Hill, RoseAnn was known to hop on a dirt bike and ride up and down the then undeveloped hill

RoseAnn worked at Shanghai Low as a waitress, St. Joseph Hospital in the Housekeeping Department and probably her most favorite job at Gottschalks. She told many stories about her and the girls and the fun they’d have working at the department store. After retirement, RoseAnn worked part time at Shafer’s Ace Hardware helping take care of the indoor and outdoor plants. Her favorite job at Shafer’s was decorating the Christmas trees each holiday season. Even this last year she made sure to make a visit to the store to see the beautifully decorated trees.

RoseAnn met and married Vern Cooney. Together they enjoyed many years of fun, laughter and shenanigans with their friends and family. As their family grew to include spouses and grandchildren, Vern and RoseAnn bought property in Phillipsville, Dean Creek and finally Trinity Lake where they loved to entertain family, friends and especially the grandchildren. RoseAnn was known to hop on a wave runner and zoom across the lake. Vern and RoseAnn also enjoyed taking the wave runners to poker runs around California. They loved to travel and enjoyed many great trips together.

RoseAnn will be known for her spirited personality, her mischievous laugh, her love for the latest fashion her granddaughters were wearing, all things sparkly, leopard print, cozy boots and blankets, a good roaring fire, her famous potato salad and meeting the Shafer’s girls for lunch and/or mimosas. RoseAnn especially loved to play cards and was always up for a game of rummy or cribbage which she played until her passing. She was always up for a good time or adventure.

RoseAnn especially loved her four boys and her grandchildren. She would do anything for them and they, in return, took loving care of her until the end – assuring she was able to be at home per her wishes.

RoseAnn was preceded in death by her husband Vern Cooney, her oldest son Kenny, her second son Ronnie, her stepfather Louis Legaz, her sister Angie Young, her father William “Bill” Quilici, her mother Lena Legaz and her granddaughter Amber Rieke.

RoseAnn is survived by her sons Jack Rieke (Michele) and Lynn Rieke Jr. (Jevonne), daughter-in law Diane Rieke, brother Mike Legaz (Jean), step-daughter Kim Cooney, step-son Vern Cooney, grandchildren Becky Hickey (Jason), Brad Rieke (Megan), Ron Rieke II, Tiffanie Rieke, Jason Rieke (Joe), Kacy Fisher (Tyson) and Patric Rieke, niece Paige Baker (Colton) many great grandchildren and great nieces and nephews .

A Rosary will be held on Saturday, March 21 at 11 a.m. at St. Bernard’s Church followed by a reception at 12 p.m. at the Ingomar Club in Eureka.

The family would like to extend a heartfelt thank you to Barbara Tupau and Elizabeth (Becca) Luifau for their compassionate care and love for RoseAnn the last 6 months.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of RoseAnn Cooney’s family. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

BOOKED

Today: 6 felonies, 11 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

Boulder Rd / Railroad Ave (HM office): Traffic Hazard

Us101 S / Fields Landing Ofr (HM office): Provide Traffic Control

ELSEWHERE

Governor’s Office: Governor Newsom honors fallen San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Office Sergeant

Governor’s Office: Governor Newsom’s schedule for February 25, 2026

RHBB: Two-Vehicle Crash Blocks Lanes at G Street and Samoa Boulevard in Arcata

RHBB: Harbor Lanes Temporarily Shut Down by Health Officials, Reopens After Fixes

OBITUARY: Cynthia Annette (Smith) Shively, 1957-2026

LoCO Staff / Today @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Cynthia Annette (Smith) Shively of Eureka passed away in her sleep on Tuesday, January 6, 2026 at the age of 68.

Cindy was born on September 4, 1957 to Larry and Nancy Smith in Hayward, Calif. She spent a portion of her early childhood in Washington with her aunt and uncle before the Smith family landed in their forever home of Eureka. Larry was a lifelong longshoreman and Nancy volunteered as a “Pink Lady” at St. Joseph Hospital. They would eventually buy Christian’s Ice Cream Parlor, renamed Smith’s Ice Creamery, where Cindy would work until the birth of her son, Cameron. She loved working there with the teens.

Cindy graduated from Eureka High School in 1975 and enrolled in College of the Redwoods. She would go on to attend dental hygienist school in San Francisco.

Cindy married her husband and love of her life, Thomas Michael Shively, on December 29, 1997 in Lake Tahoe. They would go on to buy James-Carl Painting and Decorating in 1999, which they would run together for the next 20 years until Tom’s death.

Cindy enjoyed traveling and had a love of music and concerts. She played the violin and piano. Her favorite entertainer was Elvis Presley and she visited Graceland, which was on the top of her bucket list. Cindy loved the 49ers and attended many football games throughout the years. She enjoyed going to her cabin in Ruth Lake and boating with her family and friends. She loved animals and many of us new her as the crazy cat lady. Every morning she would take great joy in feeding the family of deer that would come to visit.

She is survived by her son, Cameron Shively; step-daughter Sara Shively; grandsons Asher and Maverick Thomas Pugh; sister Dana Greathouse (Dan); niece Kyndra Williams; aunt Arline Luz; and many beloved cousins and their extended families.

Cindy was preceded in death by her husband, Thomas Shively; her parents Nance and Larry Smith; grandparents Laurence Smith Sr and Evenlyn Smith and Ernest & Anna Beidle; aunt Dorene Fowler; uncle Eugene Luz; and ex-husband Clifford Giacomini.

A celebration of life will be held on April 11 from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. in the Bay Room at the Wharfinger Building in Eureka. In lieu of flowers, memorial donations can be made to Miranda’s Rescue or the Humane Society. Cindy loved her animals!

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Cindy Shively’s family. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

Homicide Ruled Out in Arcata Woman’s Oct. 2025 Death

Sage Alexander / Yesterday @ 3:57 p.m. / Crime

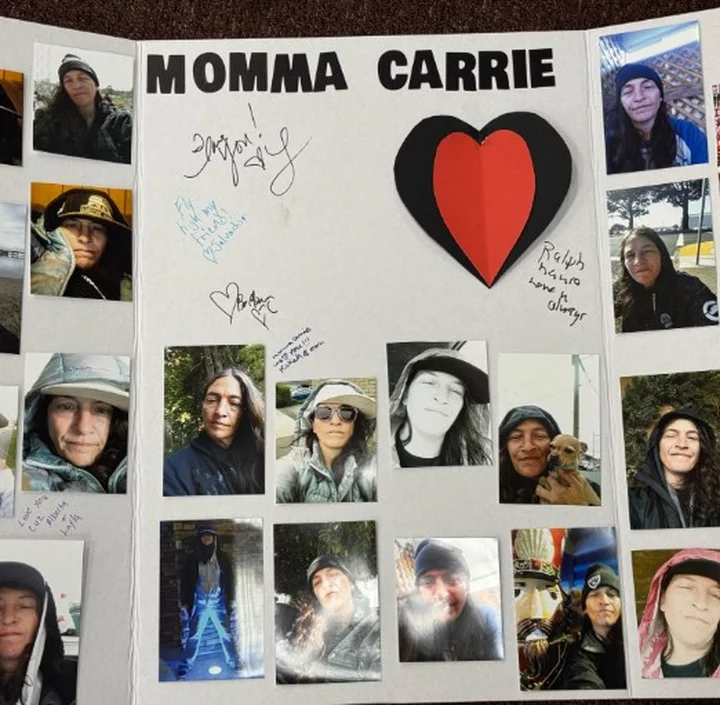

Photo: GoFundMe

The cause of death of a woman found dead in Valley West four months ago — initially believed to be a homicide — has been officially determined to be an overdose.

A report from a criminal pathologist informed the Arcata Police Department Friday that Carrie Crook, a 48-year-old and longtime resident of Humboldt County, died of fentanyl and meth toxicity.

Crook was found dead in an improvised structure by a fellow resident of an encampment, located on a vacant lot on Valley East Blvd. on Oct. 17, 2025.

The death of Crook sparked rumors and concern for weeks in the tight-knit encampment she lived in.

Witness statements and physical evidence leaned at first toward strangulation, said APD Lieutenant Luke Scown, leading to the arrest of a new-to-town man that lived nearby in the encampment.

But evidence found over the course of the investigation began to lean toward an overdose, a finding reflected by recent official toxicological results.

Scown said she was found with a mark on her neck. The people reporting her death said she looked like she’d been strangled.

Witnesses in the area, who knew her, told police she had been in an argument with a boyfriend the day before and he had put her hands around her throat.

A deputy coroner on scene initially deemed she appeared to be strangled.

“Based on the evidence that we were seeing there at the scene, along with some witness statements we were getting, it seemed reasonable she was strangled,” said Scown.

Rhett Walker, an unhoused man who recently moved to the area and was reportedly romantically interested in Crook, was subsequently arrested and booked on suspected murder charges.

He denied strangling Crook, and gave some seemingly contradictory statements to police, Scown said.

But new information turned the initial impression of homicide on its head as APD continued the investigation.

“Ultimately, we were able to corroborate Rhett’s story,” said Scown.

APD confirmed through surveillance footage and witnesses that Walker was in downtown Arcata from when Crook was last seen alive to when the report was called in.

Due to this additional information, probable cause no longer existed, and he was released without charges. At this point, “we determined he was not a suspect,” said Scown.

And other evidence reflected the death wasn’t what it initially seemed.

Following an examination by a criminal pathologist, the pathologist told APD they did not believe it was strangulation and the mark on her neck was from something she was resting against when she died.

“It was not from strangulation. The pattern and the way the mark was was not consistent with strangling someone,” said Scown. APD was informed the pathologist believed she died of natural causes or an overdose.

And last Friday, the final report by the pathologist found she died of fentanyl and methamphetamine toxicity. APD is no longer investigating the death as suspicious.

“We’re treating this as an overdose and investigating it in that manner moving forward,” said Scown.

Scown acknowledged people are likely curious why the man was arrested in the first place.

“While it is unfortunate, this is how the system is supposed to work,” he said.

He said it’s better than the alternative: letting a guilty person go because police weren’t entirely sure.

He said the department made the right choice at the moment, with the information they had.

“We were well beyond probable cause. Then, we had information that changed that,” he said.

Since her death, rumors of the circumstances surrounding it have swirled in Valley West. And scant information about a possible killer sparked fear in the community.

Crook was beloved in the community, according to Jan Carr, who feeds unhoused people in the neighborhood. She noted overdoses happen periodically in Valley West.

“This one was particularly hard. And I think it was who Carrie was,” she said.

A GoFundMe to support her children said Crook has five boys, and described her as “one of the kindest, most compassionate souls you could ever meet.” A packed celebration of her life was held in McKinleyville Nov. 23, according to the GoFundMe page.

“She’s terribly missed. She was a delightful woman. I mean delightful. I never, ever saw her without a smile,” said Carr.

Photo: GoFundMe

What’s Up With That Big-Ass Pond on E Street in Old Town Eureka?

Isabella Vanderheiden / Yesterday @ 3:44 p.m. / How ‘Bout That Weather , Infrastructure

The gigantic pond at E and Fourth streets pictured on Tuesday, the rainiest Feb. 24 recorded in Eureka since 1917. | Photo: Isabella Vanderheiden

###

If you’ve ever walked or driven through Old Town Eureka on a rainy day like today, you’ve surely noticed that enormous puddle on E Street, between Third and Fourth streets. The damned thing spans an entire city block and stretches way out into the middle of the street, with several inches of standing water lapping at the curb.

It’s been happening for years — even before the city repaved E Street back in 2023, raising the height of the street just a smidge — but why is it happening?

“[The street] needs a whole redesign,” Eureka City Manager Miles Slattery said, crediting the Outpost with having the courage to ask the hard questions. “Basically, this has been an issue for decades, and there are grading issues [on E Street] that we tried to improve, but we need to get in there and grind out some of that pavement.”

The problem is that the city’s asphalt grinder isn’t big enough to do the job, so staff will need to find a contractor to do the work. It’s something the city’s public works department has been looking at for a while now, Slattery said, but since it only affects the parking spaces on the east side of the street, it isn’t exactly a top priority for staff.

“I’m not trying to minimize the impact,” he emphasized, noting that the deepest part of the puddle is situated right in front of Councilmember Kati Moulton’s secondhand craft shop. “[The road] is low and there’s too much height in the alley.”

To get the job done right, the city will have to tear up the entire street and set different grades, which is less than ideal, given that the street was repaved just a few years ago. Cost is a factor as well, though Slattery didn’t indicate how much it’d be.

While on the note of Old Town street flooding, I asked Slattery about the big puddle that forms at E Street and Opera Alley. “That’s just a clogging issue,” he said, noting that debris can get caught in drain during regular maintenance. “That just needs to get sniped. You can call public works at 441-4203 if you see drains that are plugged up.”

Slattery also noted that staff have seen some street flooding along W. Third Street, down near SISU Extraction, especially during high tides. “We’re trying to secure some federal funding to get that fixes, but it’s going to be a major project.”

###

Rodents Strike at the Harbor Lanes Cafe, But Management and a Pest Control Service Have Already Reset the Metaphorical Pins

Hank Sims / Yesterday @ 2:47 p.m. / Health

Yesterday afternoon, a health inspector with the county’s Division of Environmental Health followed up on a citizen complaint by paying a visit to the snack bar at Harbor Lanes, Humboldt County’s last bowling alley.

The inspector found what the complaint said they would find, which was rodents.

“Observed rodent activity on Food Contact Surfaces in the back area of the kitchen as well as on shelves in the Front Kitchen service area,” wrote the inspector, employing the random-capitalization-of-nouns style that has grown so popular of late.

These rodents could not stay while the snack bar was operational, the inspector determined, so the snack bar was shut down until such time as they could be evicted.

And that was right quick, because when the inspector went back this morning everything had been sterilized and the rodents’ means of ingress and egress had been located and sealed off. So the snack shack is open again, and you can once again grab a quick burger between frames.

Here are the relevant documents:

Nice work, everyone!

Burdened With Repairing Low-Income Housing and Worried About a Future Funding Shortfall, the Arcata House Partnership Hopes that Arcata Will Try and Defray Costs

Dezmond Remington / Yesterday @ 1:18 p.m. / Homelessness

The Grove. Photo by Sage Alexander.

One-fifth of the units at the Grove, the Arcata House Partnership’s low-income housing program, are damaged beyond usability — and AHP wants Arcata to help pay for the repairs.

The Grove is home to 56 people, many of whom were once homeless. The building was, at one point, a Valley West-area motel until it was purchased by the Arcata House Partnership (AHP) several years ago. It took a $14.1 million state grant to complete the remodeling, and when it opened in late 2022 there were 60 units available for rent.

Three years later, the situation has changed. Twelve of those units are in poor-enough shape that they’re unusable. Some of them need a new kitchen; some need the paint on the walls redone; one bathroom was severely damaged by a tenant who suffered a psychotic break and tore up the walls. The Coordinated Entry system, designed by the federal department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), requires that the housing programs they fund prioritize admitting people who stand to suffer the most if they’re homeless. If a candidate is elderly, has children, or is disabled, getting them housing is a higher priority to the HUD. People with a serious mental illness can be near the top of the list; sometimes they don’t adjust well to new living conditions. Darlene Spoor, AHP’s executive director, emphasized in an interview with the Outpost that most of the Grove’s renters are doing “really well,” and they’ve only had a few tenants who’ve adjusted poorly to living in the Grove.

With so much living space unusable, operations at the Grove have slowed. AHP hasn’t been able to process and house as many people as they’d like. The situation may worsen; Spoor estimated that an additional four units will probably be unlivable within a year. She thinks AHP will need around $3 million to repair everything, though she’d like to have another $400,000 or so to cover the costs of adding an ADA-compliant sidewalk and adding solar panels.

AHP does not have the money to repair the rooms. Their funding has been unstable since the HUD changed their funding process last year, frightening AHP’s leaders to the point where they thought they might not be able to house their 31 people completely supported by HUD funds. Although the HUD later ended up giving the AHP $660,000 for their permanent supported housing programs in late 2025, that money will run out at the end of September. The income they make from the renters also doesn’t add up to much. All of the tenants pay 30% of their income (whether that’s from a job, Social Security, or General Relief), but some of them don’t earn any money and pay no rent. AHP also didn’t put aside any of the state money they used to build the Grove for later use, Spoor said.

“When we chose to develop that project, we chose to move forward knowing that we didn’t have funds for all of it,” Spoor said. “We didn’t have funds for the ADA sidewalks, and we didn’t have funds for the solar. But it was more important for us to get people in and housed, and then look for all of the other things that we need now…it was more important to get people housed sooner than later.”

AHP is banking on receiving state funds Arcata might procure. This Thursday, the city council will decide if the state Community Development Block Grants Arcata will apply for should go towards replacing water meters or fixing up the Grove. The path from state coffers to AHP via the CDGB process isn’t a straight or a sure one; the city first has to decide that it will try and secure funding for the AHP project, then apply to the state for it, and then California has to choose that project out of the scrum of other similar, competing ones. There’s no guarantee that any of those things will happen. Arcata city councilmembers Stacy Atkins-Salazar and Alex Stillman both said they were leaning towards the idea at the council meeting last week; Meredith Matthews was more in favor of using the funds to replace aging water meters. (The other two members were absent.) Arcata doesn’t have a long, successful track record of using the CDGB funds for homeless services, director of community development David Loya told the Outpost, and because of the chaos at the federal level, many other cash-poor municipalities might apply for funds out of the same small pool. All of these factors complicate the plan immensely.

Spoor is grateful for city hall’s past support, but said AHP will need more of it to continue operating. Spoor said using the CDGB grants will allow the Grove to stabilize long-term. All of their proposed projects are crucial to a lasting success, she said.

“I live in Arcata,” Spoor said. “Do I think that the water service is critical? Yes, absolutely. Do I think it’s easier to find funding for water service elsewhere than it is for affordable housing right now? Because there’s no affordable housing money anywhere right now…I think it would be easier to find funding for water infrastructure.”

“As stressful as it is for me, imagine: finally, people get stably housed,” Spoor continued. “They’ve lived through the trauma of being homeless all those years, and now they have to worry about whether they’re going to be homeless again in October. That’s horrible. That is punishment. It’s cruel.”

The Kinetic Sculpture Lab Has Moved Into Its New Home Thanks to Efforts of More Than 200 Volunteers

LoCO Staff / Yesterday @ 11:36 a.m. / Art , Community

Hooray! | Photo by Matt Filar.

###

PREVIOUSLY

- Pending Eviction, the Kinetic Sculpture Lab is Struggling to Find a Way Forward

- The Kinetics Lab Has a New Location, and This is Your Chance to Lend a Hand

###

Press release from the Kinetic Krew:

The Kinetic Sculpture Lab is overflowing with gratitude after more than 200 volunteers showed up in force to help clean, move, and re-launch the Lab at its new home at 1680 Samoa Blvd., Arcata, CA 95521.

Over two major cleanup weekends, February 7th and the February 21st, Kinetic Clean-Up volunteers rolled up their sleeves to transform the Lab’s outside space. With the incredible support of the PacOut Green Team, who joined us on February 21, the Lab community removed the equivalent of four 40-yard dumpsters of material. The scale of the effort was immense, and so was the heart behind it.

We also want to recognize the volunteers who spent Valentine’s Day showing their love in the most glorious way possible: by helping us move from our original location into our new home on Samoa Boulevard. We were blown away by the turnout. Supporters traveled from as far as Redding and Grass Valley, arriving with trucks, trailers, tools, and unstoppable energy. What could have been overwhelming became uplifting because of this community!

This transition would not have been possible without the continued flexibility and support of the Yurok Tribe, who have stood behind the Lab during this period of change. We are deeply thankful for their partnership and encouragement as we establish ourselves in our new space.

The Kinetic Sculpture Lab exists because of our community of artists, welders, dreamers, builders, movers, makers, and believers. This move wasn’t just about relocating equipment. It was about reaffirming that when this community shows up, it shows up big.

To every single volunteer who lifted, swept, hauled, organized, drove, cleaned, and cheered us on: thank you. Your time, strength, and generosity are the true engine behind the Kinetic Sculpture Lab.

We are excited for what comes next because we can’t wait to keep building, creating, and dreaming big together.

For updates and ways to get involved, follow the Kinetic Sculpture Lab on social media or stop by our new home at 1680 Samoa Blvd on Monday afternoons.

Photo by PacOut Green Team.