[UPDATED: Torn Down] New Pro-Israel Billboard Proves Controversial

Dezmond Remington / Wednesday, Feb. 5, 2025 @ 3:35 p.m. / Activism

UPDATE, Feb. 10:

Sometime over the weekend, less than a week after it was put up, the proud Zionist image was torn off of the billboard. See photos below. The Arcata Police Department is investigating the vandalism.

Lt. Todd Dockweiler tells the Outpost that the call first reporting the crime came in on Saturday, and there are no known security cameras nearby. He noted the deluge of negative responses to the billboard on social media and elsewhere, adding, “The pool of suspects is large.”

Photos by Andrew Goff.

###

Original post:

The billboard next to Highway 101.

Drivers heading south from Arcata today may have noticed a new billboard off to the right of Highway 101, a message that reads “Call me a Zionist. It only makes me prouder” against a background of a woman in front of the flag of Israel.

The slogan was put up by David Porush of San Mateo, according to the Jewish News of Northern California. Porush has also paid for a billboard reading “America and Israel: Fighting Terrorism Together” in Redwood City. Porush runs an organization called Code Blue and White and got the funding from JewBelong, a nonprofit known for its pro-Israel billboards.

Porush worked with Israel-born Arcata resident Tamar Krigel to design the slogan.

The billboard is proving controversial. One post on the Humboldt subreddit calling for its demolition has over 100 upvotes. Dozens of commenters bemoan its Zionist message and its inflammatory effect on the community.

“Cut it the fuck down,” said one anonymous commenter. “Mr. Molotov would be happy to help,” said another.

Krigel told the Jewish News of Northern California that she reached out to Parush to design a billboard after last spring’s pro-Palestine occupation shut campus down for a week.

The Outpost is waiting on a statement from Krigel.

###

[EXPLANATORY ADDENDUM: Geoff Wills, owner of local company AllPoints Signs, called the Outpost to say that while his company installed this advertisement, he does not own the billboard, nor was he involved in the sale or contract terms. As such, he asks that complaints be directed elsewhere.]

BOOKED

Yesterday: 4 felonies, 11 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

1740 Mm96 E Hum R17.40 (HM office): Traffic Hazard

Myrtle Ave / Harrison Ave (HM office): Defective Traffic Signals

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Wet Winter, Dry Reality? Humboldt Officials Say Water Risk Isn’t Gone

RHBB: College of the Redwoods Del Norte Campus Project Moving Forward with Measure I Funding

RHBB: Major Roadwork Scheduled Friday, February 6 through Thursday, February 12

Fishing the North Coast : Finally — Rain on the Way for North Coast Steelhead Rivers

(AUDIO) Humboldt Rockers Marble Jar Are the First Band to Sign the Ceiling of the New KSLG Studio (And You Can Too)

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Feb. 5, 2025 @ 1:11 p.m. / On the Air

Marble Jar in KSLG’s Old Town Eureka studio with DJ Rhi Marie

It’s a busy week for the boys in Marble Jar. This coming Saturday, the Humboldt alternative punk rock trio will celebrate this week’s release of their new album All of the Marbles with a show at the Arcata Playhouse. But before that scene coalesces, the group stopped by the Carson Block Building to hang on the air with KSLG’s very own Rhi Marie. (Listen above.)

Started by frontman Peter Ricchio back in 2010 as Peter Puffington and the Rocketship Explosion, the group has gone through several lineup changes before arriving at the current configuration that also features drummer Mitch Holmes and bassist/producer Sean “Trugg” Weikal. All of the Marbles is the band’s first full length album following the 2022 EP Losing Your Marbles and the live set Live @Blondies.

As though their album release wasn’t momentous enough, the Marble Jar crew also made some radio history this week: The band is the first (of hopefully many) to sign the ceiling of KSLG’s new Old Town studio, a tradition haphazardly conceived during their visit. Evidence of their appreciated vandalism in the pictures below. (Side note: Are you a Humboldt band doing cool things and making music that, more-or-less, fits into the KSLG vibe? Reach out at studio@kslg.com!)

Marble Jar’s album release party takes place at the Arcata Playhouse this Saturday at 7 p.m. The show features additional musical support from Crooked Teeth out of San Francisco and Unlikely from Fresno. Tickets are $15 in advance, $20 at the door and available here.

Rhi Marie interrogates Marble Jar

Marble Jar: Sean Weikal, Mitch Holmes and Peter Ricchio

History: MADE.

Are the Eel River Dams Coming Down? PG&E Releases Final Decommissioning Plan and Will Give a Public Presentation About it Tomorrow

Hank Sims / Wednesday, Feb. 5, 2025 @ 11:54 a.m. / Environment

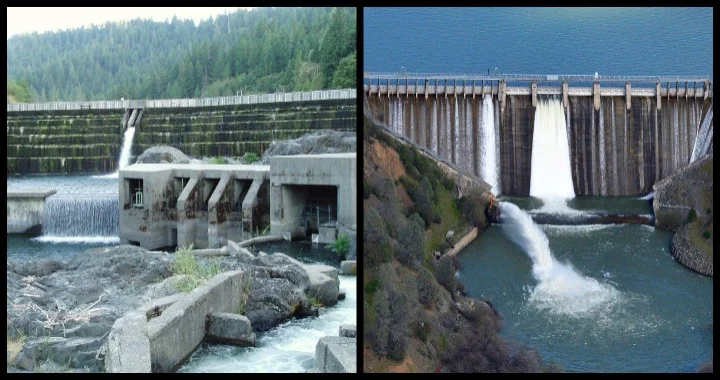

From left: Cape Horn Dam, Scott Dam. Photos: PG&E.

UPDATE, 1:08 p.m.: Here’s a statement from the County of Humboldt on PG&E’s plans.

###

Could the dams on the upper Eel River be coming down for good?

Late last week, PG&E issued a 2,000-plus-page plan to decommission and demolish its two dams on the upper stretches of the Eel River – Scott Dam and Cape Horn Dam, in Lake County and Mendocino County, respectively. These long-troubled dams were built over 100 years ago for the purpose of generating electricity, and had the side effects of rerouting water from the Eel River into the Russian River watershed. Also, they blocked fish passage into a bunch of prime habitat.

The dams have long

been unprofitable, PG&E has

been trying to get rid of them since at least 2018. They haven’t

generated any power at all since 2011 2021. Now the utility is ready to take

them down.

It all might be a lot more straightforward if not for the big interests that have grown up around the Eel River water that has, for the last century, been diverted into the Russian. When the dams first fired up, no one much cared which way the water went to the sea. It was all about generating power. But since then, agribusiness and development in the Mendocino/Sonoma/Marin corridor have come to depend on that water for their operations.

Under PG&E’s plan – you can download it here in full – both dams would be removed fairly rapidly. In their place, a new facility will be built at the site of the former Cape Horn Dam to continue to supply water to the Russian River watershed. This would be called the NERF – the “New Eel-Russian Facility.” It’s not yet clear how much water would be diverted at the NERF, but it could presumably be limited to winter months and vary depending on the wetness of the year.

“The framework here is that we will only agree to a diversion that has zero ecological impacts on the Eel,” said Scott Greacen, conservation director of Friends of the Eel, in a phone conversation with the Outpost this morning.

The main thing, for proponents of Eel River restoration, is to open up salmon and steelhead habitat beyond the dams. Cape Horn has a very bad fish ladder, and Scott Dam has no fish ladder at all. Removing those barriers could be a particular boon for summer-run steelhead, a threatened population on the North Coast.

PG&E is giving an online public presentation on their final decommissioning plan tomorrow, Feb. 6, from 10 to 11:30 a.m. Here’s the link. Public comments on the document — which will be submitted to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission — are due by March 3.

(PHOTOS) The Landslide That Claimed Shively Road

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Feb. 5, 2025 @ 9:55 a.m. / How ‘Bout That Weather

From Humboldt County Public Works:

Shively Road is one of several roads closed due to the severe weather we are experiencing. Once again, a slide came down on Monday, Feb. 3 and the road remains closed at post mile 7.26.

With ongoing storm conditions, road crews are actively storm patrolling throughout the county, responding to immediate hazards as they arise. Crews are working hard to keep roads safe and passable during the storm, but will be addressing the slide today.

Thank you for your patience.

As California’s Fire Season Grows, State Senators Push for More Year-Round Firefighters

Sameea Kamal / Wednesday, Feb. 5, 2025 @ 7 a.m. / Sacramento

Senate President Pro Tempore Mike McGuire and state Sen. Aisha Wahab talk before the start of a floor session at the Capitol Annex Swing Space in Sacramento on Oct. 7, 2024. Photo by Fred Greaves for CalMatters

Senate President Pro Tem Mike McGuire proposed Tuesday that state firefighters work year-round in place of the seasonal workforce the agency currently staffs for nine months each year. The increased duty for about 3,000 seasonal firefighters is estimated to cost at least $175 million.

“This escalating crisis has stretched firefighters dangerously thin,” McGuire said at a press conference in Sacramento, flanked by 21 other state senators and representatives from the union representing CalFire firefighters. “The threats to their health and safety along with the threats to local communities — they have never been greater.”

McGuire’s proposal is aimed at addressing California’s growing fire season — which typically lasted from June to October in the 1990s but is now considered to be from May through December, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, also known as CalFire.

The agency said it does not track how many fires occur outside of the extended fire season each year, but the CalFire website shows that two fires reported outside of the fire season in 2024, burning a total of 250 acres. No fires were reported on the website during the off-season in 2023. The extended season is driven in part by a hotter and drier climate according to research by civil and environmental engineers at the University of California, Irvine.

CalFire has about 6,100 permanent employees, in addition to the 3,000 seasonal firefighters who are typically laid off between January and March.

“For three months out of the year we downstaff one-third of our engines because of an inadequate way of staffing CalFire in today’s world,” Tim Edwards, president of the union representing CalFire firefighters, said at the press conference. “There is no fire season in California. Fires are year-round, as we just witnessed” in the Los Angeles area.

The rare January wildfires in Altadena and the Pacific Palisades killed 24 people and damaged about 16,000 homes and businesses. The state brought in firefighters from Portland and Houston, as well as from Canada and Mexico.

CalFire did not have a comment on McGuire’s proposal. But Jesse Torres, a battalion chief and spokesperson for the agency, said that more staffing wouldn’t necessarily help fight the Southern California fires due to the high winds that caused flames to spread quickly. He said a larger, year-round staff would allow more prevention work and allow firefighters to take time off.

Under McGuire’s proposal, the seasonal firefighters would be transitioned to year-round employees, and the agency’s 356 fire engines would be operational all year.

The governor vetoed a similar bill last year by Sen. Tim Grayson, a Democrat from Antioch. Newsom wrote that the state was already in the process of hiring 2,000 additional year-round firefighters because of staffing levels required in the Cal Fire union’s most recent contract, and he wrote that state civil service laws would require the temporary firefighters to apply for the permanent positions.

Asked for comment on McGuire’s proposal, the governor’s office said it does not typically comment on pending legislation. McGuire said at the press conference that his new plan would address the governor’s concerns around the legality of transitioning from seasonal to full-time by creating a new employee classification.

“We were moving at a pace that nature didn’t wait on, and the wildfires didn’t wait on,” Grayson told CalMatters Monday about last year’s bill. “We are learning that climate change continues its march forward at a pace that we must catch up to.”

The office of Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas did not respond to a request for comment on the Senate proposal.

There’s also the cost question: McGuire said the effort would be funded by the state’s general fund and would require negotiations through the budget process.

The budget is not finalized until June, however – so McGuire said he hoped his plan could move more quickly.

“I think the vast majority of Californians would like to be able to see this investment yesterday,” said McGuire, who represents the state’s fire-prone North Coast from the Bay Area to the Oregon border.

McGuire’s proposal is the latest in the Legislature’s effort to help those impacted by the wildfires in Southern California.

The Assembly unveiled a wildfire-related package last month aimed at housing recovery, including a bill to pause most new building standards, one that would accelerate state housing permit reviews and another that would ease permitting in coastal areas for accessory dwelling units.

Last week, in an effort shepherded by the governor, the Legislature also approved $2.5 billion to state and local agencies to help them oversee recovery.

The Senate Republican Caucus, representing nine of the 40 state Senators, also unveiled its own wildfire-related proposals Tuesday. The GOP plan focused on water storage, tax credits to homeowners for efforts to fireproof their properties and longer sentences for fire-related crimes.

“While Senate Republicans are encouraged by the initial bipartisan nature of the Senate’s response to the Los Angeles wildfires thus far, they remain wary of potential partisan pitfalls for this critical legislation as the plethora of past efforts have largely been blocked by legislative Democrats and the governor in years past,” the caucus said in a statement.

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

OBITUARY: Joy Gilberta Pastori, 1938-2025

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Feb. 5, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

It

is with great sadness that we announce the passing of Joy Gilberta

Pastori. Joy was born on April 5, 1938 to William and Isabella

Pasquini in Eureka. Joy passed away on January 26 at the age of 86 at

the Ida Emmerson Hospice House.

She grew up in Eureka and Vallejo. She was the best sister to her siblings Bill, John Lee and Judy. She was extremely proud that her mother was the first female traffic officer in Humboldt County. Her life changed forever on April 16, 1955 when she had a blind date with Jim Pastori, who became the love of her life. They went on to marry December 31, 1959 and were married almost 60 years. Together they owned and operated Harris and K Market and Three Corners Market for over 55 years. Their four kids — James, Cynthia, Rick and Yvette — were her world, and there isn’t anything she wouldn’t have done for them. All her children agree that having her as a mother was the greatest honor of all.

Joy leaves behind a legacy of love and laughter that no one could match. She brought joy no matter where she went. She was the best wife, mother, grandmother, sister, Aunt and friend anyone could ask for. She was her happiest when surrounded by family. She’s infamous for her great cooking, holiday decor (especially Christmas) and love of shopping. She treasured her many shopping trips with Charlene Lundblade and Jeani Vallee. Her grandkids will always remember her as the best back scratcher and their biggest fan. She and Jim traveled far and wide to catch as many of their events as they could. Her favorite place to be was their family summer home in Redway. Thankfully, Jim didn’t know all the things she let her kids get away with. She thrived in the role of “cool mom.” She was a mother figure to many and touched a lot of hearts and lives.

Joy leaves behind her loving children, Jim Pastori, Rick Pastori, Cindy (Tom) Losa, Yvette (Jason) Pastori-Ables; grandchildren Shelby (Jared) Lund, Jon (Kendra) Losa, James (Hayley) Pastori, Kendra Losa, Nicole Pastori, Colton and Kylie Ables; great-granchildren Dawsyn and Rye Pastori, Leo Lund and three more on the way; sister Judy Ford; sister-in-laws Yvonne Wahlund and Judy (Carl) Rorling; and many nieces and nephews.

Joy is preceded in death by her husband, Jim Pastori; parents William and Isabella Pasquini; brothers Bill and John Lee Pasquini; and brother-in-law Randy Ford.

In honor of Joy’s life, a celebration of life will be held on March 22 at 3 p.m. at Old Growth Cellars, 1945 Hilfiker Lane in Eureka. In lieu of flowers, the family asks that donations be made to Hospice of Humboldt.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Joy Pastori’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

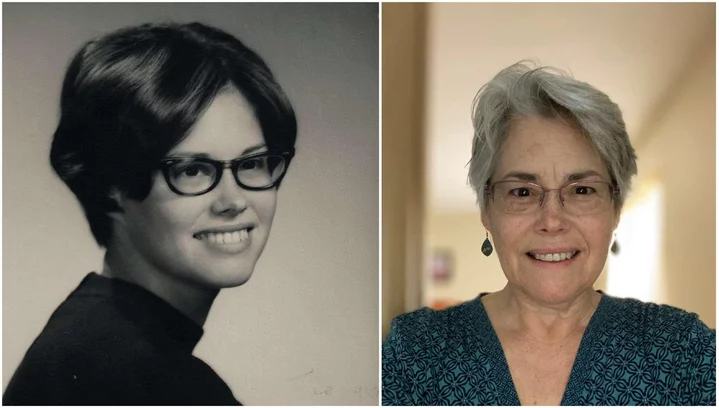

OBITUARY: Deborah Marie Jerome-Davis, 1951-2025

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Feb. 5, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Deborah Marie Jerome-Davis

June 27, 1951 – January 9, 2025

Deborah Marie Jerome-Davis was born in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, on June 27, 1951 to Conservative Baptist pastor Norman Basil Jerome (1912–1993) and his devoted wife and Christ-follower, Catherine Marie Hozey-Jerome (1921–2012). At the age of six, Deb prayed with her mother to receive Jesus as her Lord and Savior and became a Christ-follower herself.

At her side when she entered Heaven’s gate were her husband of more than 40 years, Daniel Dean Davis (Dan), her daughter, Deanna Marie Davis-Lugo (1990), her son, Daniel James Ollie Davis (1993), and one of her two sisters, Darlene Edna Jerome (1954). Deb is also survived by her sister, Cynthia Dawn Jerome (Cindy, 1960).

When Deb’s mother married Norman, a widower, in 1950, he brought two sons into their marriage, both of whom preceded Deb in death: David Stephen Jerome (1940-1957) and Daniel Lee Jerome (Dan, 1946-1994; wife, Miriam). Deb delighted in sharing photos and memories she had of her half-brothers, and she cherished Dan and Miriam’s sons, Jason, Aaron, Ethan and Nathan and their families.

A dedicated and accomplished teacher, Deb earned her B.A. in Education from the Philadelphia College of Bible and her M.A. in Elementary Education from Temple University. Her career spanned teaching public and private elementary school students in Pennsauken, New Jersey and Arcata.

Deb and her brother, Dan, shared a close bond. When Dan and Miriam served as missionaries in Kofu, Japan, Deb joined them as a live-in tutor and teacher for their two oldest boys, Jason Lawrence Jerome (wife, Ruth) and Aaron Smith Jerome (wife, Jennie). She cherished their younger brothers, Ethan William Jerome (wife, Bethany) and Nathan Norman Jerome (wife, Vali). Later, Deb moved with Dan and Miriam to Okinawa, Japan, where she continued her passion for education by teaching elementary students at Okinawa Christian School.

As Providence would have it, Deb met a young Marine, Dan Davis, shortly after arriving on Okinawa and they were engaged within a year. Dan separated from the Marine Corps in August 1983 and returned to Humboldt County where his father’s family settled in 1948 and where he was born and raised, and Deb left the island about a year later after fulfilling her OCS commitment. They were married on July 21, 1984, at Doylestown First Baptist Church and settled in the McKinleyville-Arcata-Eureka area, near where Dan was born and raised.

While Dan returned to Humboldt State to complete his bachelor’s degree in computer information systems, and after briefly substituting at a local public elementary school, Deb began teaching fourth graders at Arcata Christian School, continuing until Deanna’s birth on April 15, 1990. Their faith was deeply tested when Deanna was born with a life-threatening condition called TEF (tracheoesophageal fistula). They faced this challenge with prayer, the support of close friends, skilled medical professionals, and modern technology. With the help of their McKinleyville Baptist Church family, Deanna overcame those early struggles, an experience that ultimately strengthened Deb and Dan’s faith and their relationship.

In 1991, Dan was transferred from the community bank (Bank of Loleta) he had worked at in Eureka, since before they were married in 1984, to U.S. Bank in Portland, Oregon. They made their home there for the next 27 years. Their beloved son, Daniel, was born into the family on May 16, 1993. Deb homeschooled Deanna until Daniel entered kindergarten, when they both enrolled at Portland Christian School, Deanna graduating in 2008 and Daniel in 2011.

Deb and Dan found their Oregon faith family at Montavilla Baptist Church until about 2001, where Deb served as a teacher and a Women’s Retreat speaker and Dan served as a teacher and elder, among other roles. Deb would later serve as Women’s Ministry Coordinator and Dan as Men’s Ministry Coordinator and elder at Greater Gresham Baptist Church (now Pathway Church).

After 22 years in their SE Portland home, in 2018 Deb and Dan found a new home in nearby Columbia County and a new church family at Grace Baptist Church Warren. Deb settled in quickly, leading a home Bible Study with several Grace ladies and some of their friends from other churches. Dan took a little longer to find his way and then began attending Men’s Ministry events and activities like Men’s Bible Study, Men’s Breakfast and Man Camp. He would later volunteer to serve as Men’s Ministry Team Leader.

On April 20, 2022, Deb was diagnosed with ovarian cancer and began a journey that neither she nor Dan ever imagined for her, themselves or their family. Through invasive surgery and painful chemotherapy, immunotherapy and a few clinical trials, Deb’s joy and faith in God’s sovereignty over her life never wavered: “I am absolutely certain God will heal me, either miraculously this side of Heaven, or through my doctors’ hands, or as I die and pass into Heaven.”

In early 2023, after the cancer returned, Deb committed to reading through the Bible to highlight key verses for Deanna. She completed that read-through and markup on December 31, 2024, nine days before she would see her Savior face-to-face. In December 2024, after learning the cancer had spread to her heart and lungs, Deb made the difficult decision to accept hospice care. She used her remaining days to meet with her small group for a Christmas gift exchange, and several of her friends and family in person and in online meetings to say goodbye and share her faith. She called these “meaningful conversations.” Deb prayed especially for Bay Scholl, a young member of Grace Baptist Church, whom she adopted as a Prayer Buddy and met with twice.

On the afternoon of Thursday, January 9, 2025, Deb left us to meet her Heavenly Father. She will be remembered as a Godly, loving, and joyful Christ-follower and loving daughter, sister, aunt, wife, mother and friend. She is already greatly missed by all who knew her.

You are invited to join the family to honor Deb at a graveside service at Greenwood Cemetery, Arcata, at 1 p.m. on Saturday, February 15, 2025. Deb’s ashes will be interred there near the graves of Dan’s father and stepmother, Lawrence Corley Davis (1922–1995) and Mary Rowena Campbell-Davis (1929–2021); his paternal grandparents, James Albert Davis (1890–1959) and Ollie May Corley-Davis (1897–1969); and one of Lawrence’s two brothers, James Riley Davis (1930–1991).

In honor of Deb’s memory, those who wish to contribute are encouraged to support Voice of the Martyrs, a cause close to her heart, by visiting www.persecution.com. Your generosity will help support persecuted Christians worldwide.

Deb’s prayer for Dan, Deanna, Daniel and you is found in Numbers 6:24-26 (NLT):

May the LORD bless you and protect you.

May the LORD smile on you and be gracious to you.

May the LORD show you his favor and give you his peace.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Deb Jerome-Davis’ loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.