Majority Owners of Shuttered Redwood Meat Co. Sell Their Shares to Accused Animal Abuser Ray Christie

Ryan Burns / Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2024 @ 4:11 p.m. / Business , Courts

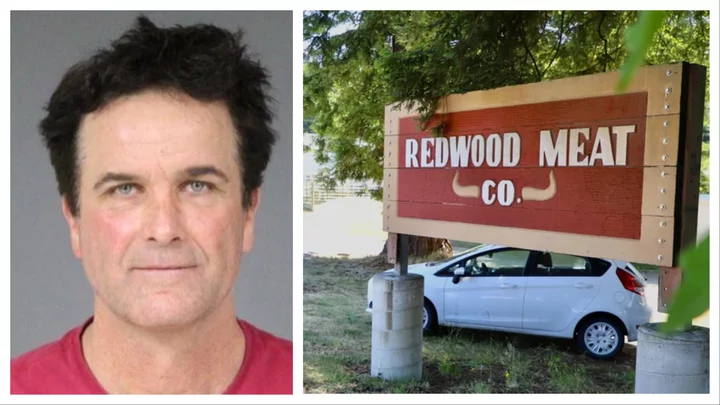

Christie (booking photo) and Redwood Meat Co. (file photo)

###

PREVIOUSLY:

- Humboldt Ranchers and Farmers Left Scrambling After Closure of Redwood Meat Co., the Region’s Only USDA-Certified Slaughterhouse and Processing Facility

- In Lawsuit, Minority Shareholders of Redwood Meat Co. Accuse Their Father and Cousin of Fraud, Embezzlement, Document Shredding and More

###

In the midst of being sued by members of their own family for alleged fraud and embezzlement, the majority owners of Redwood Meat Co. sold their shares of the recently shuttered business to notorious Arcata rancher Raymond F. Christie, whose trial on felony animal cruelty charges was delayed in December 2022 due to his ill health.

John “Punk” Nylander and his nephew Ryan Nylander sold their 82 percent stake in the business to Christie last Tuesday, Aug. 6, despite a temporary restraining order issued the previous week that prohibits them from selling or transferring any Redwood Meat Co. assets or taking any actions that require shareholder approval.

In a declaration to the court, Sacramento attorney Stuart L. Smith, who’s representing Christie, argued that last week’s sale of company stock was completely legal per the terms of a 40-year-old shareholder buy-out agreement that was signed by the company’s then-owners. Smith only recently became aware of this particular document.

“Under the terms of the operative transactional documents, John Nylander sold his entire 444 shares and Ryan his entire 378.75 shares to Mr. Christie for fair value,” Smith says in his declaration. “Consequently, Mr. Christie is the majority owner of Redwood Meat Company Inc, having acquired eighty-two (82) percent of its outstanding shares.”

In their recently filed lawsuit, the minority shareholders — Stephanie Nylander, Rachel Nylander Flores and Russel Nylander, who collectively own about 5.4 percent of the business — argued via their attorney, Cyndy Day-Wilson, that their dad (John Nylander) and cousin (Ryan) were attempting to sell the business without their knowledge or required shareholder approval.

The suit further alleges that, facing $900,000 in debt to the IRS, their family members were looking to offload the business after years of criminal mismanagement, including breach of fiduciary duty, unjust enrichment and document shredding.

The next hearing in this case is scheduled for Friday morning. The plaintiffs are seeking a preliminary injunction to prohibit Redwood Meat Co.’s shareholders from selling any company assets, including stocks, until the court case is settled. Of course, since John and Ryan Nylander already sold their stake in the business, such an injunction would be akin to closing the stable door after the horse has bolted, as the saying goes. But Day-Wilson may ask the court to invalidate the transaction.

Locals likely remember Ray Christie as the rancher convicted of numerous misdemeanors for dumping more than 250 dead cows in open graves near state waters on his Arcata Bottoms farm. His 2019 trial on felony animal cruelty charges was declared a mistrial when one of the 12 jurors refused to convict him. A retrial was indefinitely postponed in 2022 due to Christie’s worsening medical issues, including a cancer diagnosis, a heart condition and vascular issues.

Christie also stood trial in 2009 for allegedly raising roosters for cockfighting and possessing dozens of cockfighting implements. That trial also resulted in a hung jury, and the charges were ultimately dropped.

The latest court filings — some of which were posted online last week by John Chiv — include a declaration submitted to the court by local attorney Dustin Owens, who is representing Redwood Meat Co., the business, but not John or Ryan Nylander.

In his filing opposing the preliminary injunction, Owens argues that such an order would be “improper as a matter of law” and would “prevent the Company, arguably, from reopening or conducting any business whatsoever which would no doubt result in the absolute destruction of the Company’s value.”

Redwood Meat Co. is worth at least $1.5 million, according to Owens, who bases that figure on the recent stock transfer to Christie.

“The annual cash flow for the Company in 2023 was $719,219.68 according to the Company’s general ledger,” Owens writes.

He goes on to say that Ray Christie has big plans for Redwood Meat Co.

“Mr. Christie intends to aggressively restructure the company, rehire key employees and other staff that were furloughed, and reopen the Company so that it may profitably operate,” he writes in his brief to Judge Timothy Canning.

Owens argues that the preliminary injunction shouldn’t be granted because the plaintiffs can’t possibly succeed on the merits of the case, in part because they’re trying to prevent a deal that already took place.

“Injunctions have no application to alleged past wrongs that have already occurred,” he argues.

###

PREVIOUSLY in Ray Christie:

- (VIDEO) Drone Flight Reveals Mass Open Grave of Cattle Carcasses in Arcata Bottoms

- Mass Open Cattle Grave Bulldozed; Location of Carcasses Now Unknown

- Cops Raid Notorious Ranch in the Arcata Bottoms; Rancher Ray Christie Arrested at the Scene

- More Than 250 Dead Cows Found on Ray Christie’s Properties, Says HCSO; Numerous Other Alleged Violations Discovered

- Humboldt-Del Norte Cattlemen’s Association Calls Ray Christie’s Ranch ‘Horrific,’ Says Anyone Convicted of Animal Abuse Should be Punished to the ‘Greatest Extent Possible’

- Rancher Ray Christie Held to Answer for Three Felony Charges of Animal Abuse; Four Charges Dropped After Investigating Deputy’s Testimony Was Compromised

- Judge Reverses Own Decision in Christie Animal Cruelty Case; Arraignment Set For Next Month

- Calling State Law ‘Unconstitutional,’ Attorneys for Rancher Ray Christie Ask Judge to Throw Out Case Involving Hundreds of Cattle Carcasses Found on His Land

- CHRISTIE TRIAL: Hung Jury Declared After One Juror Out of 12 Declines to Convict Accused Rancher

- RETRIAL: Following Hung Jury, Rancher Ray Christie Will be Retried on Four Felony Counts in February, Prosecutor Says

- Arcata Rancher Ray Christie Set to Face Second Animal Cruelty Charges in January

- CHRISTIE CASE: Defense Presents Aggressive Case for Charges to be Dismissed, Based on Allegations of Police Evidence Tampering

- CHRISTIE CASE: Rancher Battling Cancer as Second Trial Looms

- Second Ray Christie Trial Postponed Due to Defendant’s Deteriorating Health

- Trial of Arcata Rancher Ray Christie Delayed Yet Again, as the Accused’s Medical Problems Worsen

BOOKED

Today: 5 felonies, 11 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Friday, Feb. 20

CHP REPORTS

2000 Loop Rd (HM office): Trfc Collision-No Inj

4332 Mm101 N Hum R43.30 (HM office): Trfc Collision-1141 Enrt

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: High Winds Knock Out Power to Thousands Across Del Norte and Humboldt Counties

AP News: ICE begins to purchase warehouses, but some owners are backing out of deals

Reuters: US Secret Service agents killed man trying to unlawfully enter Trump’s Mar-a-Lago

The Guardian: Floreana giant tortoise reintroduced to Galápagos island after almost 200 years

Did You See That Big Ship in Humboldt Bay Last Week? That’s the Vessel Mapping the Seabed and Collecting Data for Offshore Wind Development

Isabella Vanderheiden / Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2024 @ 12:13 p.m. / Offshore Wind

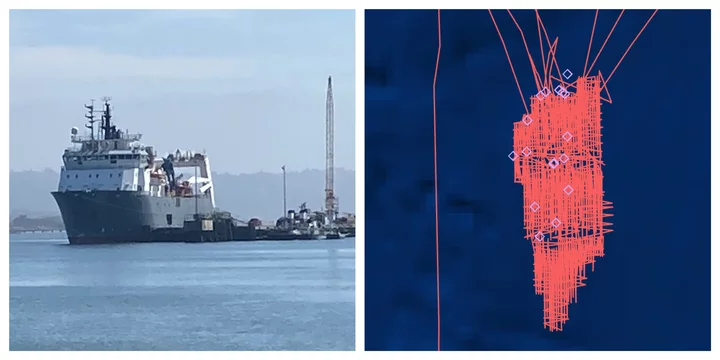

Left: The Ocean Guardian docked in Humboldt Bay (image submitted). Right: The Ocean Guardian’s path while surveying the Humboldt Wind Energy Area, located 20 miles offshore.

###

If you’ve walked along the waterfront in the last week or so, you may have noticed a big ol’ ship docked in Humboldt Bay. That was the Ocean Guardian, a survey vessel that’s been busy helping offshore wind developers map the ocean floor off the coast of Eureka.

RWE announced in June that it would begin initial site surveying for the Canopy Offshore Wind Farm, one of two floating offshore wind projects slated for the Humboldt Wind Energy Area (WEA), located approximately 20 miles west of Eureka. Before environmental review and site planning can begin, offshore wind developers and researchers need a clearer picture of the alien world that lies beneath the ocean’s surface.

RWE has been using an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) designed by Norway-based subsea surveying company Argeo to map the seabed within the Humboldt WEA, where water depths range between 2,400 to 3,200 feet. You can think of an AUV as an underwater drone. It is a self-propelled underwater robot that uses multibeam sonar, side scan imaging and sub-bottom profiling to map the ocean floor below.

Through this process, RWE will assess the best locations for installing floating wind turbines and electric transmission lines and help developers “better understand biodiversity, habitats and other environmental factors to ensure responsible planning and design” within the Humboldt WEA.

Asked for a progress report on the site surveying process, Canopy RWE spokesperson Ryan Ferguson said the Ocean Guardian has been out at sea for more than a month. (You can check out the vessel’s path on this map.) If you saw it docked in Humboldt Bay last week, that’s because the crew had to stock up on fresh food and other necessities before heading back to the ship’s home port in Washington.

The vessel is in the final stage of the initial survey work. “Our team will now spend the next couple of months processing, reviewing and interpreting the data,” Ferguson said.

Before the site surveying began earlier this summer, a couple of folks from the RWE Canopy team sat down with EcoNews Report host Tom Wheeler to talk about the site surveying process. You can find the full interview at this link.

Eureka Man Arrested for Attempted Homicide After Allegedly Firing Weapon During Verbal Dispute, Eureka Police Say; Long Police Standoff Last Night Ends Peacefully

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2024 @ 9:53 a.m. / Crime

Press release from the Eureka Police Department:

On August 13, 2024 at approximately 10:16 p.m., Officers with the Eureka Police Department (EPD) were dispatched to the 700 Block of Creighton Street in Eureka for a report of a verbal argument inside a residence. The reporting party then heard a suspected gun shot and found a bullet hole in their residence.

Officers arrived on scene and set up a perimeter around the suspected residence where the gun shot came from. An occupant of the residence, who was no longer on scene, was contacted and stated she was in an argument with the male suspect in the residence and as she was leaving he picked up a gun and shot at her. The female was not injured during the incident. Officers continued working on contacting the male inside the residence using different modes of communication but received no response.

EPD Detectives obtained a search warrant for the residence as well as an arrest warrant for the male suspect. The Incident Commander requested the assistance of the Humboldt County SWAT Team as well as negotiators from the Crisis Negotiation Team (CNT). Personnel on scene worked through the night to contact the male and resolve the situation.

At approximately 5:30 a.m., negotiators contacted the male and were able to have him surrender to officers that were on scene. The suspect, Ken McCarty (49-year-old from Eureka) was taken into custody without incident. McCarty was transported and booked at the Humboldt County Jail on charges of Attempt Homicide, and Shooting into an Inhabited Residence.

This is an ongoing investigation and anyone with information about this incident is asked to contact EPD Detective Bailey at 707-441-4300.

The Eureka Police Department would like to thank the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office, including SWAT and CNT, Humboldt Bay Fire, and City Ambulance for their assistance during this incident.

Boise Fire Nearly Doubles in Size Since Yesterday, Up to an Estimated 7,200 Acres

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2024 @ 8:12 a.m. / Fire

Photo: Incident management team.

Press release from Six Rivers National Forest:

Quick Facts:

- Acres: 7,223 (flown at approx 10 p.m., some area to the east was unreadable due to smoke.)

- Detection Date: August 9, 2024

- Containment: 0%

- Cause: Under investigation

- Crews: 18

- Engines: 30

- Dozers: 4

- Helicopters: 12

- Total Personnel: 610

- Fixed wing: available as needed

Information: Here.

Headlines

No structures have been reported as damaged or destroyed despite yesterday’s significant fire run.

Join us TOMORROW, Thursday, August 15 at 2 p.m. for an online Ask the Incident Commander information meeting. Link TBD.

Get all your Boise Fire information in one mobile-friendly place! https://linktr.ee/

There have been no changes to evacuation status since the start of the incident. Evacuations are in place for the Boise Fire for residents near the fire area in Humboldt County. For the most current evacuation information please visit the Boise Fire linktree or visit—

Humboldt County: https://humboldtgov.org/356/

Siskiyou County: https://www.co.siskiyou.ca.us/

Leader’s Intent: The Boise Fire is being managed with a full suppression strategy.

Operational Update:

Critical fire behavior was observed yesterday after the inversion lifted and the fire got into alignment with the Boise Creek drainage. The growth was primarily to the east.. Crews had spent the previous days opening and improving lines along Antenna Ridge and those were defended overnight west of Orleans Mountain although significant spotting occurred. Crews were able to get hose lays into the area after activity decreased, and they continued to contain and mop up those spots into the early morning hours. Despite the fire activity, crews were able to continue firing off the Antenna Ridge Road to deepen containment to provide protection for Orleans. Structural assessments will continue today with a large influx of resources coming in to assist. Crews began looking for opportunities to contain the fire on its east side yesterday. This could include locating and re-opening previous fire lines.

Weather and Fire Behavior:

The weather today is anticipated to be similar to yesterday, with cooler temperatures and good overnight moisture recovery. All the elements remain in place for active fire behavior after the inversion lifts in the afternoon. Fuels remain critically dry in the fire area, and the fire has been primarily driven by those heavy, dry fuels and the area topography.

Californians Will Vote on a $18 Minimum Wage. Workers Already Want $25 and More

Jeanne Kuang / Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2024 @ 7:54 a.m. / Sacramento

Maria Maldonado, the California Fast Food Workers Union statewide field director, leads a panel at the union membership launch event in Los Angeles on Feb. 9, 2024. Photo by Jules Hotz for CalMatters

California touted a victory for working people in 2016 when it enacted a sweeping series of minimum hikes, making sure the lowest-wage workers would earn at least $15 an hour by 2022.

Then-Gov. Jerry Brown, while signing the law, spoke of “giving people their due;” then-Senate leader Kevin de León spoke in Spanish of making it possible to achieve the American dream.

Now, California voters are being asked to boost the statewide minimum wage again, just two years after the landmark $15 wage championed by unions and embraced by Democratic politicians nationwide took effect.

But when Proposition 32 — the measure to raise the minimum wage to $18 next year — was confirmed for Californians’ ballots in November, it wasn’t with the same fanfare.

That’s because a lot has changed:

- The current law came with boosts tied to inflation, which has pulled the statewide minimum wage steadily up to $16 this year — and which will bump it up to $16.50 in January.

- The skyrocketing cost of living has prompted local officials in more than two dozen cities to enact their own, faster-growing minimum wages since 2016. Now, 40 cities and counties have a higher minimum wage than the state. Most are in the Bay Area or Los Angeles County, covering an estimated one-third of California’s low-wage workers. Several are already above $18, or just one inflationary bump away.

- Unions in California took a different approach. They’ve won industry-specific wage floors for fast food, health care and, in some cities, hotels that are well above the statewide minimum. Fast food workers, who got a raise to a minimum of $20 in April, are seeking an inflationary bump for next year. In Los Angeles, hotel and airport workers are demanding a $25 minimum wage and a raise to $30 in time for the 2028 Olympics.

- Many low-wage workers received more amid a tight labor market during the pandemic, marking the first economic recovery in two decades in which they got raises faster than higher-wage workers.

This year in the Legislature, business and labor groups focused on other fights, and it was uncertain whether the measure would even stay on the ballot. Some proponents argued it wasn’t nearly ambitious enough to help the working poor afford California, where MIT researchers estimate the average single, childless adult needs $27 an hour to be “self-sufficient.”

One of them, the workers’ advocacy group One Fair Wage, asked the sponsor to pull it from the ballot in favor of advocating for a $20 wage; the organization’s president, Saru Jayaraman, now says Prop. 32 is needed but only a “first step.”

And though the sponsor, investor-turned-anti-poverty advocate Joe Sanberg, said he believes the measure will make a difference in workers’ lives, even he openly agrees $18 “is not enough.”

“In some ways, at the point where this measure is heading to the ballot, it’s kind of underwhelming,” said Chris Tilly, a UCLA professor of urban planning who studies labor markets.

Hotel workers and Unite Here Local 11 supporters sit-in during a protest at one of the main entrances to LAX airport, on June 22, 2023. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for CalMatters

It’s not that workers, and their advocates, are uninterested.

The campaign estimates 2 million workers would still get a raise under the ballot measure — but that’s significantly fewer than the 4.8 million calculated by UC Berkeley economist Michael Reich in 2022, when the measure was first proposed and then delayed because Sanberg missed an administrative deadline. Under the measure the minimum wage would be $18 in January, with a delay until 2026 for employers with fewer than 26 workers.

Gustavo Miranda is one worker who would benefit. The 32-year-old Pomona resident makes $16.50 an hour sorting packages and loading trailers at an Inland Empire warehouse. Rent — $1,000 a month — swallows nearly 40% of his income, and he said grocery prices have risen. To make ends meet, he spends weekends refereeing youth sports. A raise, he said, would help him with car payments and sending money to support his daughter.

In the Central Valley, Stockton retail worker Donna Bowman said she’s been left behind by the state’s raising wages for other industries. The 55-year-old works part-time nights at a Dollar General to supplement her Social Security payments, and said the price of gas has forced her to cut back visits to her grandchildren.

“I don’t know how, with the way things are right now, and inflation, the government expects you to live on $16 an hour,” she said.

Proponents are banking on that simple message to convince voters. “From the standpoint of people who are going to be voting, the question is very clear,” Sanberg said.

After Sanberg poured more than $10 million into gathering signatures for the measure in 2022, the proponents have hardly spent anything. They don’t have a campaign account after Sanberg shut it down earlier this year.

“I don’t know how, with the way things are right now, and inflation, the government expects you to live on $16 an hour.”

— Donna Bowman, retail worker in Stockton

But organizers including Ada Briceño, co-president of the Southern California hotel workers’ union UNITE HERE Local 11, say the measure is naturally popular and could turn out votes for other races.

The most powerful proponent, the California Labor Federation, which represents 2.3 million union members, isn’t yet sure how much effort it’s going to put toward passing the measure. While the federation was not involved in qualifying the measure, it endorsed it in July and plans to include it on other statewide campaign materials.

“I just don’t know how much opposition there will be, quite honestly,” said Labor Federation president Lorena Gonzalez.

Gonzalez sees the ballot measure as a “way to move things forward” at a time lawmakers are unlikely to take up the minimum wage. “When we jumped to $15 and did it legislatively, that was really profound,” she said.

But $18 today?

“Sure,” it makes a difference, she said, but “it’s not really a living wage.”

Cook Tony Peña prepares food at El Rincon restaurant in the San Ysidro neighborhood of San Diego on April 16, 2024. Photo by Adriana Heldiz, CalMatters

Opposition is still organizing.

A legislative deal and a state Supreme Court ruling resolved what would have been the biggest ballot fights between business and labor — a law allowing workers to sue their bosses and a ballot initiative that would have asked voters to make it more difficult to raise taxes.

So business groups say they’re now turning their sights toward Prop. 32. Three major employers’ groups with deep pockets — the Chamber of Commerce, the California Grocers Association and the California Restaurant Association — are leading the opposition.

Chamber CEO Jennifer Barrera said employers will also focus on a simple message: the threat of price hikes.

“There is a heightened sensitivity to the impact of increasing these labor costs on businesses and what that ultimately does for the cost of living,” she said. “Our belief is that the cost of living is directly impacted when you raise these costs on businesses. There’s only so many places where they can make adjustments.”

That warning could resonate with voters pessimistic about an uncertain economy.

Opponents point out Gov. Gavin Newsom this year, facing lower-than-expected tax revenues and a yawning budget deficit, delayed the state’s new $25 minimum wage for health care workers until the fall out of concern the state could not yet afford it. Private employers, they said, should be given the same time to adjust. Newsom has not taken a position on Prop. 32, and several spokespeople did not respond to inquiries from CalMatters in the last two weeks.

Unemployment in California is 5.2%, higher than the national 4.1%, and youth unemployment is worse. Business groups contend that increases in the minimum wage cause employers to offer fewer opportunities to less-experienced workers, though many economists disagree wage hikes directly lead to unemployment.

Reich, of UC Berkeley, last fall published a study with other academics finding the ramp-up to a $15 minimum wage in California and New York had little effect on employment in fast food and among youth — and in the post-pandemic years that industry even added jobs.

But employers point to recent local minimum wage hikes as test cases — particularly the small, relatively wealthy community of West Hollywood, which last year set what was the nation’s highest wage floor of $19.08 and required generous paid sick leave. (This year, Emeryville surpassed that with an inflation-induced $19.36, in another display of cities leaving $18 in the rearview.)

West Hollywood officials this year commissioned surveys in which 42% of business owners said they laid off staff or cut workers’ hours, and city council members agreed to pause the next wage increase until January. Part of the city’s challenge was that business owners had to compete with employers just down the street in Los Angeles, where the minimum wage is $17.28, and Beverly Hills, which uses the state minimum of $16.

Walter Schild, owner of a West Hollywood restaurant, said the policy forced him to raise the wages of servers who were making the minimum wage but received substantial extra income in tips, leaving little room to also give raises to back-of-house staff, who were making about $19 to $21. He said he eliminated three jobs, including a baker and a barista, and cut a third of the restaurant’s hours, but the business is “barely surviving.”

Schild called minimum wage hikes a “misguided” decision that makes little dent in the cost of living. A wage of $18 or $19 hardly makes rent affordable in West Hollywood anyway, he said.

“I don’t think the minimum wage is supposed to make sure everyone can afford rent in their area,” he said. “This is not supposed to support a family … We ought to have an environment where people can gain skills.”

The restaurant industry, still recovering from pandemic-induced losses and food price inflation, is likely to make up the bulk of the pushback to the measure. Many were already shaken up by the $20 minimum wage for fast food workers that started in April.

“I don’t think the minimum wage is supposed to make sure everyone can afford rent in their area.”

— Walter Schild, restaurant owner in West Hollywood

It may be too soon to tell the actual effects of the fast food increase, though proponents and opponents have both touted monthly jobs figures at convenient times. The latest seasonally adjusted federal employment numbers — recommended by experts because the restaurant workforce typically peaks in the summer and shrinks in the winter — show California fast food jobs have dipped since a high point in January, but remain close to last summer’s levels. Overall, the industry has about 20,000 more jobs than before the pandemic.

Still, stories of job cuts have spread, and some workers report having hours cut after receiving the raises. Some chains have hiked prices, too.

Erik Freeman, CEO of the Sacramento-based 40-restaurant chain Jimboy’s Tacos, said he’s worried restaurants are reaching a tipping point where increasing labor costs will force them to raise prices to a level consumers can’t afford.

Most of the chain’s nearly 500 workers make $16 to $20, Freeman said. Because of its relatively smaller number of stores, Jimboy’s was not subject to the fast food wage hike. But the restaurants still saw decreased sales, and Freeman suspects it’s because price hikes at other chains changed consumers’ habits. He estimated in his restaurants, there’s a 3% decrease in sales for every 5% increase in prices, which he said may have to happen if wages are raised.

“Any price increase that we do at this point, we’re concerned about pricing ourselves out of the market,” he said. “There’s never been a time that (restaurant owners are) as worried about it as they are now.”

Other business owners say they’re more or less prepared for a rising minimum wage.

“It has been on this path for the last several years,” said Katya Christian, co-owner of her family’s cabin-leasing resort in the Sierra Nevada. “We try to anticipate it.”

The seasonal business hires a handful of college students during the summers to maintain the property and accommodate guests. Christian pays most of them the minimum wage, and this year raised the cabin’s rates to make up for the past few years of wage hikes.

She said she’ll likely vote for the ballot measure, acknowledging if it passes her business is more able to absorb such increases because her customers can typically afford higher prices. Then, perhaps a year after a new wage kicks in, she said, she would likely raise the cabins’ rates.

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

OBITUARY: Christine Minta Mengel, 1949-2024

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Christine Minta Mengel was born in Ashland, Oregon on April 8, 1949

to Norman and Doris Bergstrom. At the age of three the Bergstrom

clan, including son Gregory, moved to Fort Dick in Del Norte County, where Norman worked as an assayer. In 1959 they moved a bit further

south to Humboldt County, where the family settled on Hill Top Drive

in Fortuna. During her years living in Fortuna Doris taught her to

sew, knit, and do needle point. Christine was also active in 4-H all

throughout her school years, and she entered her works in many fairs

winning a second-place prize, two third-place prizes, and a gazillion

blue first place ribbons. She once won the wool contest at the

Humboldt County Fair and the prize was a whole week with other 4-H

winners in Hawaii. Coincidentally, her future husband, unbeknownst to

either of them, was in Hawaii at the same time on his way to Vietnam.

Christine was always incredibly humble about her successful endeavors, which included more than one Teacher of the Year for Small Schools awards, and so many more, too numerous to list. She had enough awards and prize ribbons to paper almost every wall in the house, but instead of showcasing her many accomplishments she instead relished in the wins, both big and small, of her beloved husband Ward, son Carl, numerous nieces and nephews, and the children that were lucky enough to call her Mrs. Mengel.

Christine loved children and with her best friend Patty Schuler went off to Humboldt State University to earn a degree in Education so that she could be a teacher. And what a teacher she was: Her kids loved her, the kids’ parents loved her, and she was generally loved all around. She lived to teach and did so for 39 years at Rio Dell Elementary. Some of the teachers and staff that she was very fond of included Diane Porter, Debbie Andrews, John Dimmick, and Mary Varner (apologies if we’ve forgotten anyone, she really did have so much love for so many).

Before finding and marrying her lifelong partner, Christine and Diane Porter would take many trips together growing to be lifelong friends to this very day. When she was 29, the handsome Mr. Ward Mengel entered into her life, crossing paths at a dance club. Ward asked her to dance and he never let her go for the next 46 years. They were married in the Methodist Church in Fortuna on June 24, 1978. Not too long thereafter arrived their only son Carl Maxwell, who was doted on and did not want for much as the only grandchild of Norman and Doris. That being said, you won’t find a harder worker than Carl.

Being a school teacher afforded Christine a few months off each year, and Ward was able to take advantage of his long tenure at his job to take off a month each summer. They made the most of their time and traveled through many states and Canadian provinces, having so much fun and creating wonderful memories and stories to take back to the classroom.

Christine was involved in many community groups such as the Soroptimist International of the Eel river Valley. During her 12 years as a member and officer she had another opportunity to visit Hawaii. Her favorite part though, was being in charge of “Girls of the Month”, in which each month one girl from local high schools would receive an award and $50 for academic excellence. She loved the meetings and the people and missed few opportunities to engage over those 12 years.

She was also a member of the Garden Club taking part in home tours, flower sales and teas. She and Diana Porter had a corner plot downtown Fortuna and we were all very proud of it. Christine also attended church and took part in United Methodist Women’s group. Christine was an amazing mother, wife, friend, sister, and aunt who’s smile was infectious and her laugh an easy thing. She did not have a want for friends, and she will be missed dearly by those that knew and loved her.

Christine is survived by husband Ward Mengel, and son Carl Mengel (wife Tonya, kids Kayla and James); brother Gregory Bergstrom; brothers-in-law Lowell Mengel II, and Russell Mengel (wife Donna); sister-in-law Marie Cochrane; and many nieces and nephews. Christine was predeceased by her parents Norman and Doris Bergstrom.

A service will be held at Methodist Church in Fortuna at 1 p.m. on Saturday, August 17, 2024. In lieu of flowers please consider making a donation to an organization Christine would appreciate: Hospice, Soroptimist, Garden Club, 4-H, etc.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Christine Mengel’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.

TODAY in SUPES: Sheriff Honsal Chafes Against Call for Civilian Oversight; Board Considers Responses to Civil Grand Jury, Denies Blocksburg Glamping Project

Ryan Burns / Tuesday, Aug. 13, 2024 @ 4:56 p.m. / Local Government

Humboldt County Sheriff William Honsal. | Screenshot.

###

This afternoon, as the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors considered its responses to the latest batch of Civil Grand Jury reports, Sheriff William Honsal argued vehemently against the idea of establishing new independent oversight of his office.

In its first report of the year, the Civil Grand Jury recommended that the county set up an independent Civilian Oversight Board and an Office of Inspector General, both with subpoena power, to provide enhanced understanding and oversight of the Humboldt County Sheriff Office. The oversight board would be charged with reviewing the office’s handling of critical incidents and allegations of misconduct, so that “the people of Humboldt County can gain a clearer view of important events that affect all of us,” as the Grand Jury put it in a press release.

But in comments to the board, Honsal argued that there’s no need for such additional oversight given his office’s existing level of transparency and the measures already in place to handle allegations of misconduct.

“When I look at this report and when I look at the climate within the county, I don’t see the controversy,” Honsal said. “I don’t see the need to establish a sheriff’s oversight. … What I’m asking is, what aren’t we currently doing right now? What is it that the Sheriff’s Office isn’t being transparent about?”

Elaborating on a statement posted yesterday to the Sheriff’s Office’s Facebook page, Honsal said he has personally ensured since being elected that things in his office are done correctly and transparently, adding that if he were to do anything wrong, he would be held accountable at the ballot box.

Honsal also said that allegations of serious misconduct can be investigated by existing bodies, including the California Commission on Peace Officers Standards and Training (POST), the Department of Justice, the District Attorney, the Board of Supervisors, the Human Rights Commission, the Grand Jury and the public.

Resuming a conversation it started three weeks ago, the board (minus Supervisor Steve Madrone, who was absent) wasn’t prepared to establish such oversight at today’s meeting. Instead, they were considering whether to establish an ad hoc committee to investigate the merits of such a decision.

Fourth District Supervisor Natalie Arroyo said she sees value in exploring community opinions and researching what other counties and cities are doing in this regard. She also said the board has a responsibility to “understand the execution of duties of our employees,” telling Honsal that while the concept of an oversight board may sound punitive, that’s not her intent.

“We’re living in a domain where people expect different things from law enforcement than they did 10 or 20 years ago, and I think it behooves us to have the opportunity to set up an ad hoc and talk about that, and to bring back a little bit more information,” Arroyo said.

Third District Supervisor Mike Wilson said an oversight committee could help the community gain trust and understanding by peeling back some layers of potentially daunting bureaucracy between them and the Sheriff’s Office. He also pushed back on the notion that voters can easily hold a sheriff accountable, noting the strict requirements to run for the office and the regularity with which Honsal runs unopposed.

While Madrone was absent, he called in during this discussion to voice his interest in serving on the ad hoc committee and his support for the creation of an oversight board. He said there have been “numerous critical incidents that should have been reviewed and were not,” adding that community oversight is about the entire department, not the individual at its head.

First District Supervisor Rex Bohn, who keeps a “Thin Blue Line” flag hanging in his window, said he supports the sheriff and his deputies and agrees with Honsal that there are ample existing means of accountability.

Second District Supervisor Michelle Bushnell expressed interest in serving on the ad hoc committee, as did Arroyo.

During the public comment period, a couple of members of this last Civil Grand Jury clarified their arguments, with Larry Giventer reiterating the position that oversight is constructive, not punitive. And former foreperson Richard Bergstresser pointed to the example of the City of Eureka’s Citizen Oversight of Police Practices (COPP) board, saying, “Sunshine is always good.”

The board wound up voting unanimously to create an ad hoc committee of Arroyo and Bushnell, who will work collaboratively with Honsal, District Attorney Stacey Eads and a representative from the County Administrative Office to explore the Grand Jury’s recommendations.

Other Grand Jury responses

Earlier in the meeting, Public Information Specialist Catarina Gallardo ran through staff’s proposed responses to two other reports from the 2023-24 Civil Grand Jury: “Humboldt County Facilities: Owning vs. Leasing” and “Humboldt County Custody & Corrections Facilities.”

Regarding the prior one, Gallardo said staff agrees with the Civil Grand Jury’s central finding that it would be more cost effective if the county owned buildings rather than leasing them, though she said the county has already completed a variety of consolidation goals and is working steadily toward further co-location of county offices.

As for the second report, most of the facilities in question fall under the authority of Sheriff Honsal, who prepared his own set of responses. The Civil Grand Jury found that the county’s custody and corrections facilities all suffer from understaffing, and some have deferred maintenance needs.

Staff recommended that the board partially agree with a finding that a gap in pay is making it harder for the county to recruit juvenile corrections officers, since the board recently approved a pay raise that narrowed that gap. Staff said the board should disagree with a finding that the Coroner’s Office lacks a central computerized data system, because it has such a system. And Gallardo said the board should not implement some recommended repair projects since the Sheriff’s Office is taking care of them.

The board unanimously approved staff recommendations.

Hemp legislation letter

Turns out you can get high on hemp. This traditionally less-potent incarnation of the cannabis plant — often used in the production of paper, clothing and food products (hemp milk, hemp oil, hemp protein powder, etc.) — enjoys less-stringent regulations under federal law. In fact, the 2018 Farm Bill made it federally legal to grow hemp and ship it across state lines or even internationally, as long as it contained less than 0.3 percent THC.

But a loophole in the Farm Bill allows THC levels in hemp to be measured by weight instead of its power to intoxicate. Consequently, there has been “a flood of intoxicating hemp products” in gas stations and online stores, “making it incredibly easy for consumers and youth to access,” according to a county staff report.

There’s now a bill advancing through the state legislature, AB 2223, that would crack down on such sales through new regulations, but Humboldt County Planning and Building Director John Ford said there are significant local concerns about the proposed new law.

By co-regulating hemp alongside cannabis, the bill would allow hemp to enter the state’s legal weed marketplace, putting hemp products grown in and imported from across the country in direct competition with Humboldt-grown cannabis, which is subject to much more stringent regulations.

Staff asked the board to sign a letter opposing the bill unless it’s amended to do the following three things:

- Include a ban on incorporating all forms of hemp-derived THC into cannabis products;

- Establish a maximum THC threshold for hemp products at non-intoxicating levels; and

- Establish a clear statutory definition for synthetically derived cannabinoids.

The timeline is incredibly short: AB 2223 could pass from the Assembly to the Senate for approval as soon as Thursday, and if the Senate votes to approve it before the end of the current legislative session on Aug. 30, the measure would head to Gov. Gavin Newsom’s desk to be signed into law.

Public commenters said this is cause for serious alarm.

“There’s a few things that get my hands sweaty and my heart racing, and when the governor can just make one swoop of his pen and literally destroy everything we have built here, it is really, really concerning,” said Craig Johnson, co-owner of Alpenglow Farms.

Ross Gordon, policy director with the Humboldt County Growers Alliance, said allowing out-of-state hemp to be sold in California dispensaries would upend the marketplace. He complimented staff on the draft letter.

Ford said other counties, including Mendocino County and Nevada County, are also giving this bill the side-eye and will likely send similar letters.

The Board of Supervisors approved the letter unanimously.

###

Twinkle Acres glamping permit denied

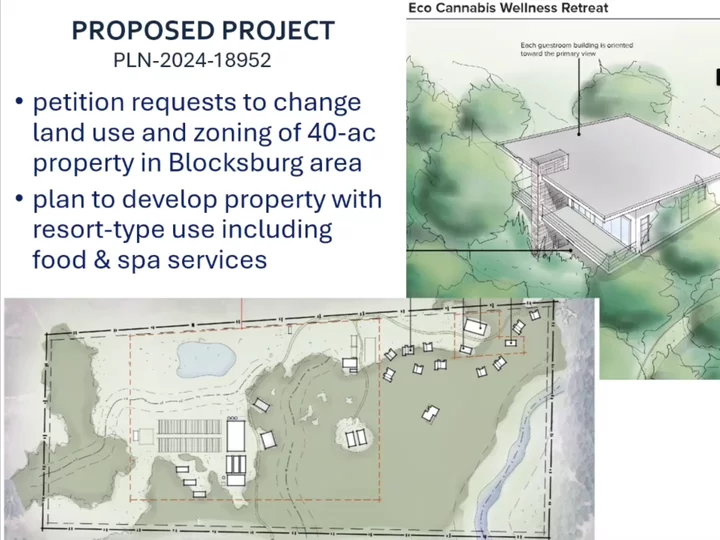

Conceptual drawings for a proposed eco-cannabis wellness retreat. | Screenshot from county staff presentation.

###

During the board’s morning session they considered an application from commercial cannabis farmers with a 70-acre parcel near Blocksburg. They’re looking to establish a weed wellness retreat where guests would stay in casitas and enjoy accommodations such as an onsite pool, restaurant, spa, creative studios, sand volleyball court and more.

The owners filed a petition for a General Plan Amendment and Zone Reclassification to allow these uses, but Senior Planner Steve Lazar explained that the county’s current General Plan doesn’t really allow for the “spot zoning” that would be required to approve the project.

He added that the proposal conflicts with county policies designed to prevent lands zoned Agriculture Exclusive (AE) from being converted to non-agricultural uses. But county staff sees the value in this kind of proposal, which could draw tourists to the region.

“We’re asking you to both deny this petition but also direct our department to begin work on ordinance revisions to the zoning regulations to enable uses of this sort in certain scenarios,” Lazar said.

While he was in the midst of his staff presentation, Bushnell noted that the project site looked very close to her own property. The board took a break to investigate, and when they resumed the meeting a few minutes later, Bushnell confirmed that her parcel shares a boundary with this one, so she had to recuse herself.

Wilson voiced concerns about approving such development in a high-risk wildfire zone that doesn’t fall within an existing fire protection district. Arroyo agreed, saying that while this is “a really cool concept,” she understands why there are concerns.

Bohn said he thinks the fire danger could be mitigated through project requirements, and projects like this one could “show off our area.”

Property owner Paul Mitchell said he’s been talking to county staff about the potential to expand hospitality services on his land “given the climate of the cannabis industry right now.

“I think, in this community, that’s what makes the cannabis experience so unique, is the landscape, and it offers an experience that nobody else can really offer, except for southern Humboldt,” Mitchell said.

Industry representatives, including Natalynne DeLapp of the Humboldt County Growers Alliance, urged the board to have staff develop policies to allow such glamping.

“It is really a potential boon for our rural areas that are not currently supported by the farm stay model,” DeLapp said.

The three board members who were present and eligible to vote unanimously approved staff’s recommendations, denying the petition while directing staff to start working on an ordinance addressing rural visitor-serving uses and glamping by the end of June 2025.