OBITUARY: James ‘Jim’ Robert Marvel, 1960-2024

LoCO Staff / Saturday, Aug. 31, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

James ‘Jim’ Robert Marvel

December 22, 1960 - June 3, 2024

With the heaviest hearts, we announce Jim’s passing on June 3, 2024, at 63. Jim was born on December 22, 1960, to Joe and Peggy Marvel of Eureka.

Jim was a kind and loving soul with the most beautiful distinguished eyes — one green and one blue — but it was his heart captured everyones attention. He attended Eureka Senior High, graduating in 1979. After that, he became a glazier journeyman, working in general construction and security after graduating from the police academy. Before retiring, he worked as a maintenance director at a skilled nursing facility, where he always shared God’s word with the residents and employees. Jim was a unique and compassionate individual who touched the lives of everyone who knew him. If he were not working, Jim would be writing, and few had the opportunity to read his treasured excerpts and how all of his writings would start with the phrase, “From quill to keyboard, the path has not changed, who can harness the inspiration of the blank page?” He left many beautiful letters to his family that they would read for years.

James was an active Pine Hill Baptist Church member for many years, serving as the youth pastor. He often influenced the younger generations to serve at the local food kitchen and took them on memorable adventures, such as horseback riding and kite flying. James’s favorite role was that of a grandparent. He treasured his time with his grandchildren and loved being their Papa, never missing a recital or sporting event.

He is preceded in death by his loving mother, Peggy Lightfoot; his father, Joe Marvel; his eldest son, James Jr. Marvel; and daughter, Jessica Marvel.

Jim is survived by his children Chelsey and Emmanuel Herrera, Ashley and Jose Chiu, and Joseph Marvel; as well as his handsome grandsons Jace James and Malakai Nehemiah; and his breathtaking granddaughters Jessica Grace, Nina Alejandra, Mia Allaia, Kamillah Rose, and Priya Anisah. His stepfather, Larry Lightfoot; his siblings, Joe and his wife Pam and their families; Linda and her husband Dave and their family; Larry and his wife Kellie and their family; and Diane and her husband Brad and their family.

His love for his family was evident in every moment he spent with them.

A celebration of life will be held in November 2024, and details of the event will follow.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Jim Marvel’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.

BOOKED

Today: 8 felonies, 5 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

Silkwood St / Hiller Rd (HM office): Traffic Hazard

Us101 S / Redcrest Ofr (HM office): Live or Dead Animal

1850 MM101 N DN 18.50 (HM office): Traffic Hazard

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Klamath-Trinity Joint Unified School District to Reopen Tomorrow

RHBB: Hoopa Valley Police Believe Suspects No Longer in the Area

RHBB: Suspicious Device Prompts Road Closure in Rosewood Neighborhood

Mad River Union: Plaza Grill restaurant reopening April 8

OBITUARY: Margaret Patricia Huffines, 1946-2024

LoCO Staff / Saturday, Aug. 31, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Margaret

Patricia Huffines

February

27, 1946 - June 25, 2024

“Meg” was one of seven children borne by Margaret P. Atkins in Greensboro. N.C. Preceded in death by her mother, father Garland Huffines, stepfather “Papa” Sam Atkins, sister Anne Harris, brother Ray Huffines, and her husband and soulmate David Carlson, Meg is survived by daughter Phaedra O’Connor, sons Damion Sharpe and Simon Carlson, grandchildren Aurora, Sebastian, Fallon, Leif, Gwen, and Samary, great-grandchildren Vernon and Emillie, brothers J. Stephen Huffines, William H Atkins, Sam W Atkins, James F Atkins, David’s brothers Paul and Peter and sister Ruth, former husband Chip Sharpe, her cousin Susan Womack, and best friend Dianna Horne.

Meg graduated from Greensboro Senior High and nursing school and began her career as a nurse. Later, with her masters degree, she became a nurse practitioner and also taught nursing school classes. In the 1970s, the formative years of Arcata’s Open Door Clinic, she was a dedicated provider of medical TLC.

Meg was an activist for peace and equality for all people. She traveled extensively with her husband David with infectious laugher, love, and compassion. She taught us to be fully in the present.

In the last years of her life Meg was fortunate to be able to spend time with family in Greensboro, North Carolina, and come live with her daughter Phaedra and granddaughter Fallon in Olivehurst, California. She had just returned from a week-long visit with her son and grandson Damion and Sebastian in Eureka and enjoyed a visit from her son Simon and granddaughter Samary before entering the hospital for surgery.

She lived a full, happy, colorful life. She traveled much of the world enjoying life with passion, purpose and deep love of family. She will be missed. Take a deep breath, appreciate your heart, and your connection to others in memory of her.

Meg will be interred in Arcata. Please bring memories of Meg to a Celebration of Life on Monday, September 9, at 2 p.m., at the Humboldt Unitarian Universalist Fellowship on Jacoby Creek Road.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Meg Huffines’ loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.

Cal OES Kicks In $$$ for Last Year’s Emergency Repairs to Ferndale Fairgrounds’ Grandstands

LoCO Staff / Friday, Aug. 30, 2024 @ 4:47 p.m. / Local Government

Earthquake-related repairs being made on the grandstands in August 2023. Photo via Humboldt County Public Works.

###

Press release from the County of Humboldt:

On Dec. 20, 2022, a 6.4 magnitude struck Humboldt County. Following the initial earthquake, the county experienced over 200 aftershocks, one of which being a 5.4 magnitude on New Year’s Day 2023 that resulted in a significant increase of reported structural damages.

The earthquakes that shook Humboldt County caused damage to many structures, including the grandstands at the Humboldt County Fairgrounds in Ferndale.

In early 2023, a structural engineering inspection determined that the grandstands at the fairgrounds were not safe for public occupancy due to earthquake-related damage. In June 2023 the Board of Supervisors unanimously approved a $1 million financing plan to fund the repairs the grandstands, ensuring they would be safe for the public to enjoy when visiting the fairgrounds. Temporary shoring repairs on the grandstands were completed in August of 2023. These repairs stabilized the grandstands to an acceptable safety level for public occupancy while permanent repairs are designed and implemented.

Costs accrued for repairs to earthquake-related damages to the grandstands were submitted to the state as part of the reimbursement process, and the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (Cal OES) recently reimbursed the county just over $836,200 for the majority of costs for initial earthquake-related repairs made to the grandstands. This reduces the county’s contribution for the temporary grandstand repairs to approximately $164,000. The $836,200 that was reimbursed to the county can now be used for other priority capital infrastructure repair or replacement projects.

Immediate results in long-term disaster recovery are challenging to achieve and the Humboldt County Department of Public Works continues to work in partnership with Humboldt County Fair Board and Cal OES to determine the best course of action for implementing permanent repairs to the grandstands and other buildings at the fairgrounds that were damaged by the earthquakes.

For more information and updates on Humboldt County’s Public Works Department projects, visit humboldtgov.org/publicworks.

###

PREVIOUSLY:

- The Ferndale Fairgrounds’ Grandstands Are in a Perilous State of Disrepair, So the Board of Supes is Holding an Emergency Meeting Tomorrow to Discuss Possible Solutions

- THE FAIR MUST GO ON! Humboldt Supervisors Pony Up $1 Million to Fund Emergency Improvements to the Grandstands at the Ferndale Fairgrounds

TREMENDA ATMÓSFERA! Plaza Grill Will Shut Down Next Month, But the Arcata Staple Will Morph Into ‘Havana,’ a Cuban-Californian Joint

LoCO Staff / Friday, Aug. 30, 2024 @ 2:27 p.m. / Food

The stately Plaza Grill. Photo via its Facebook page.

Press release from Plaza Grill:

Plaza Grill is both excited and sentimental to announce that it will be transitioning at the end of September into a new Cuban-Californian fusion restaurant.

Plaza Grill has been serving delicious, thoughtfully prepared food on the third floor of Jacoby’s Storehouse in Arcata for over 35 years. Over the time, thousands of patrons have dined and enjoyed their experience at the restaurant through great food and personal customer service. Plaza Grill is both proud and honored to have served three generations of our amazing community. Still today, many of those customers enjoy food and drink at the restaurant regularly. However, as the years go on, ownership has decided that it is time for an exciting new restaurant that they are sure the community will love to take over the space.

Havana is a Cuban-Californian Fusion restaurant that will be bringing its classy atmosphere into the Plaza Grill space in the beginning of October. Owners Shona and William have been operating a renowned restaurant in the capital city of Cuba for the last eight years and are excited to bring their authentic and enticing cuisine to Arcata this fall. The restaurant will be serving dishes that blend the flavors of Cuba and California to create an experience that Humboldt County has never had before. In addition to delicious plates, they’ll also be delivering unique cocktails crafted by world-renowned mixologists and providing a space for visitors to commune, dance and more.

Throughout the month of September, Chef Asa Maguire and Mixologist Yosvany Gonzalez will be working with the Plaza Grill team and offering unique Cuban dishes and drinks in addition to the familiar Plaza Grill menu. Asa Maguire is a talented chef who has brought his talents around the world, including New York City, San Francisco and of course, Cuba, where he learned and practiced authentic Cuban cuisine and he is excited to take what he’s learned to Arcata. Cuban Mixologist, Yosvany Gonzalez, is a world-class bartender who has spent recent years mixing up cocktails throughout Las Vegas. He loves crafting unique drinks that cater to the setting and feeling of the atmosphere and looks forward to capturing a blend of Cuba and Arcata.

Of the closure of one of Arcata’s most beloved restaurants and the opening of what they expect will be a new one, Plaza Grill owners Bill Chino and Chris Smith said,

“We are endlessly thankful to have had the opportunity to serve Humboldt County for almost four decades. Nothing will ever replace the smiling faces of regulars and the delightful conversations we’ve had with so many guests over the years. We look forward to serving each and every one of you all throughout our last month. As for the opening of Havana, we couldn’t be more excited to have such a unique restaurant coming to fill the space. The owners and team are wonderful people and we know that local foodies will love what they have to offer.”

Plaza Grill will continue to offer customers its signature menu throughout September with the addition of various Cuban-Californian dish and drink specials. Those interested in an early sneak peek at Havana can visit on Sept. 19 for a pop-up event of the soon-to-be restaurant!

To stay up to date and learn more, please follow Plaza Grill and Havana in Arcata on Facebook and Instagram.

Two Arrested With Weapons and Drugs Following Thwarted Construction Yard Heist, Sheriff’s Office Says

LoCO Staff / Friday, Aug. 30, 2024 @ 1:26 p.m. / Crime

Hoisington, Russell. Photos: HCSO.

PREVIOUSLY:

###

Press release from the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office:

Following up on the Kernen Construction theft and pursuit that occurred on Aug. 12, 2024, deputies developed information regarding the location of the suspect.

On Thursday, Aug. 29 at about 6:30 p.m., Humboldt County Sheriff’s deputies responded to the 1400 block of Fay St. in Samoa to attempt an arrest warrant on Joshua Hoisington, age 42 of Blocksburg, Calif., who was involved in a theft and pursuit case that began earlier this month.

Deputies showed up to the residence, served the warrant, and thoroughly searched the location but did not locate Hoisington. During the search, they discovered firearms and drug paraphernalia at the location. While on the scene, deputies found Hoisington’s significant other, Deana Russell, offsite near the residence. Russell was taken into custody due to an outstanding felony warrant for probation violation.

The following property was discovered by deputies at the searched location:

FNH 5.7x28 pistol

Liberty 21.22 LR revolver

Ruger 10/22

Approximately 1,000 rounds of various caliber ammunition

5.32g of methamphetamine

Methamphetamine pipe

8g of suspected psilocybin mushroom

2g of suspected fentanyl

Later that night, deputies located Hoisington on a traffic stop and was taken into custody without incident.

Both Hoisington and Russell were booked on the following charges:

Having a controlled substance while armed (H&S 11370.1(a))

Felon in possession of a firearm (PC 29800(a)(1))

Prohibited person in possession of ammunition (PC 30305(a)(1))

Possession of Large-Capacity Magazines (PC 32310)

This case is still under investigation.

Anyone with information about this case or related criminal activity is encouraged to call the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office at (707) 445-7251 or the Sheriff’s Office Crime Tip line at (707) 268-2539.

A Week of Wildlife Weirdness at the Arcata Marsh

Hank Sims / Friday, Aug. 30, 2024 @ 12:01 p.m. / Wildlife

CASE ONE: THE SWALLOW

On Tuesday morning, something in the swirl of barn swallows over the Marsh caught Martin Ludtke’s eye, and he managed to get video of it. Check it out:

Video: Martin Ludtke.

Did you see that?

If not, watch it again, and note that one of those swallows is white.

Knowing nothing about birds, the Outpost went to its go-to Bird Man, Rob Fowler, who confirmed Ludtke’s ID. This is an ultrarare white swallow — hard to tell whether it’s albino or leucistic from this distance — and Fowler noted that other local Bird People have spotted this sucker around the bottoms as well.

“Pretty cool to see a Barn Swallow like this!” Fowler affirmed.

Indeed, once you think to pose the question the Internet shows that Bird People around the world habitually lose their shit over such a sighting. “One in a million!” enthuses Ebro Delta Birding. “Once in a lifetime!” NestWatch raves. “Lower mean phenotypic values than other birds!” gushes Evolution: International Journal of Organic Evolution.

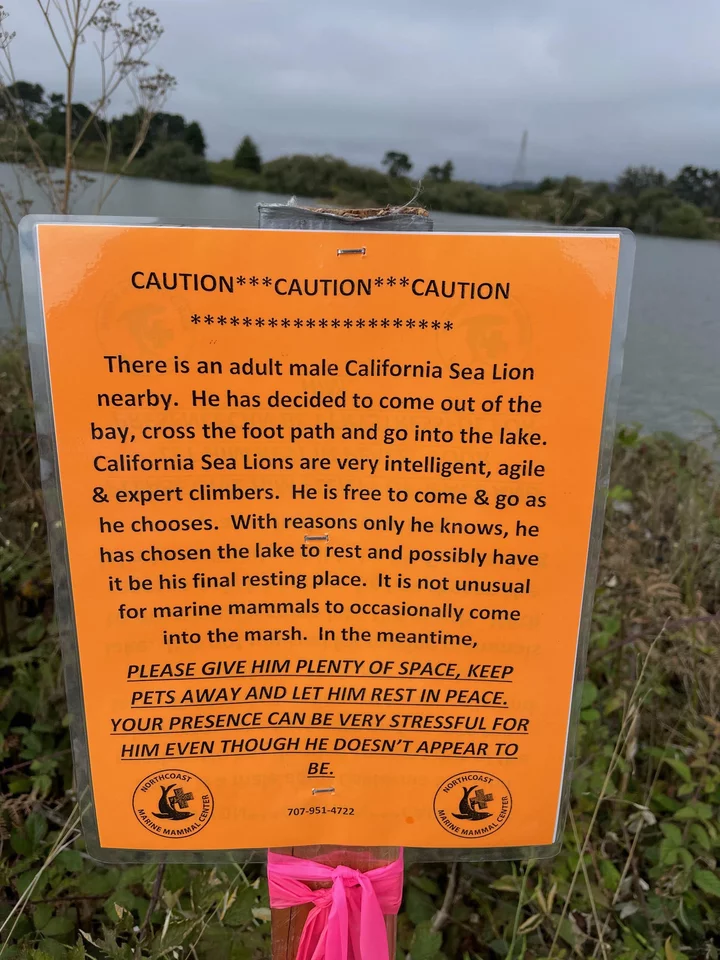

CASE TWO: THE SEA LION

On a sadder note: Earlier this week people started to notice the strange sight of a California sea lion swimming in Klopp Lake.

Photo: Jen Kalt.

The consensus seems to be that this sea lion has chosen this place to die.

This sea lion is known to science. According to a write-up by local biologist Dawn Goley, he was tagged up in Astoria in 2017, whence he wandered up to British Columbia and now down to Humboldt.

The important thing is to remember is that if you see this guy on your stroll around the Marsh, you must give him a very wide berth — not only for his sake, but your own. Sea lions can be aggressive and unpredictable and, as Goley says, they’re a lot quicker than you think.

There’s a chance that this animal could be suffering from leptospirosis. You’ll want to be especially aware of that if you’re bringing your dog to the Marsh, according to science-adjacent Friend o’ the LoCO Jen Kalt. As in: If your dog isn’t vaccinated for lepto, or if you aren’t sure if it is, you’ll want to avoid the area entirely.

Here’s a photo of an informational poster that the Northcoast Marine Mammal Center has erected at the site:

Photo: Kalt.

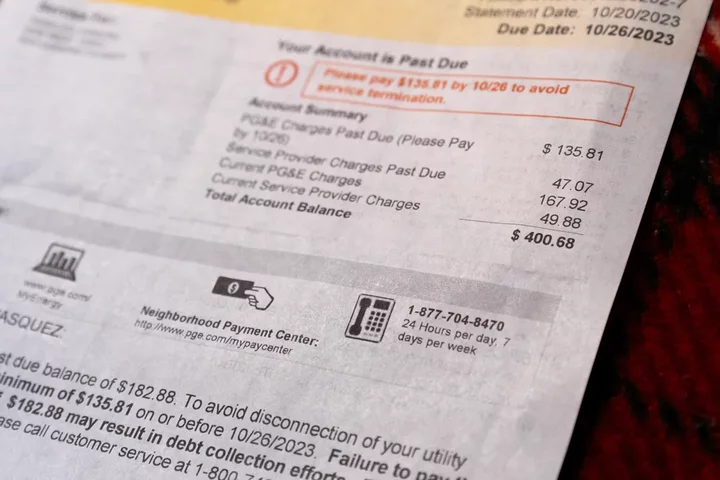

A Stunt or First Step? Inside California’s Last-Minute Effort to Cut Electric Bills and Streamline Clean Energy

CalMatters staff / Friday, Aug. 30, 2024 @ 7:29 a.m. / Sacramento

A consumer’s PG&E bill from October, 2023. Photo by Manuel Orbegozo for CalMatters

The Legislature and Gov. Gavin Newsom have significantly scaled back their eleventh-hour plans to reduce Californians’ electric bills and fast-track renewable energy projects.

Many experts said the proposed measures now amount to a political gesture or, at best, a small first step toward solving the problems, rather than nuts-and-bolts, enforceable steps that would give consumers financial relief or help speed solar and wind projects.

The main proposal addressing California’s rising electric bills would give each household a small, one-time credit of between $30 to $70, according to a person familiar with the bill. The measure would save an estimated $500 million.

It’s uncertain whether the scattershot, gut-and amend-approach will win the Legislature’s approval by Saturday, the deadline for when all legislation for the year must be approved.

For weeks, top lawmakers and the governor’s aides have negotiated a series of proposals aimed at addressing California’s twin clean energy challenges: meeting mandates for clean, carbon-free energy and reducing electric bills that are among the highest in the nation.

By the Wednesday night deadline, the state’s leaders unveiled six bills that address the cost of electricity and building of renewable energy projects.

Environmental groups, clean-energy businesses and consumer advocates have mixed feelings about all of them, with some saying they are largely ineffective and others saying they are a good first step.

“The last minute…backroom deals do not attack the root causes of California’s incredibly high energy bills. Instead, they take away key funds from programs that work to create a sham (consumer) bill reduction.”

— Loretta Lynch, former president of the California Public Utilities Commission,

Loretta Lynch, an environmental consultant and former president of the California Public Utilities Commission, told CalMatters that customer bills are climbing because the commission keeps giving the green light to rate increases. The Assembly measures wouldn’t address the biggest drivers of costs to consumers, she said.

“The last minute, gut-and-amend backroom deals do not attack the root causes of California’s incredibly high energy bills,” she said. “Instead, they rob Peter to pay Paul — taking away key funds from programs that work to create a sham (consumer) bill reduction.”

But Mark Toney, executive director of The Utility Reform Network, supported the measures, saying they are “an important first step towards affordable energy for all California residents.” He has called lowering consumer costs an urgent priority because the state could lose public support for clean energy.

Molly Croll, director of Pacific offshore wind for American Clean Power, a renewable industry group, said she was surprised by the streamlining proposal and has no position on it, since it wasn’t anything the industry lobbied the Legislature for. “We haven’t had input,” she said echoing comments from other renewable energy groups.

“This is a two-year effort. Anything worth its weight in life, anything big and bold, takes time. But we’re committed.”

— Senate President Pro Tem Mike McGuIre

Senate President Pro Tem Mike McGuire, a Democrat from Santa Rosa, told CalMatters he would try again next year by bringing back more proposals.

“This is a two-year effort,” he said. “Anything worth its weight in life, anything big and bold, takes time. But we’re committed.”

Californians have seen their electric bills nearly double over the last decade as the state’s biggest utilities have passed on spending from reducing wildfire risks and transitioning rapidly away from fossil fuels. Rates are expected to continue to outpace inflation through 2027.

Two measures authored by Assemblymember Cottie Petrie-Norris, a Democrat from Irvine, aimed at reducing energy bills were introduced Wednesday night by gutting and amending two unrelated bills.

Assembly Bill 3121 would require consumers to be paid funds — reportedly amounting to the single $30 to $70 credit for each household — from a few consumer energy programs in areas served by Southern California Edison, Pacific Gas & Electric and San Diego Gas & Electric.

Included is a program that provides upgrades to school heating and air conditioning systems, and two programs that help low-income Californians save on their energy bills with incentives for installing solar panels and rebates for energy storage.

Advocates for the programs say the proposed cuts would harm low-income Californians and children.

“It is a pound-foolish decision that doesn’t address the systemic (energy) affordability crisis we’re facing,” said Stephanie Seidmon, program director for UndauntedK12, a nonprofit that helps public schools transition to clean energy. “It feels more like a political stunt and it’s unconscionable we would do that to our children, our staff members and our teachers who come to schools that are not always safe learning and working environments.”

Jennifer Robison, a Pacific Gas & Electric spokesperson, said the company hasn’t taken a position on AB 3121, but supports returning money to customers from the programs.

“PG&E shares the legislature’s and Governor’s focus on making energy bills more affordable for our customers. We’re working to stabilize bills and limit average annual bill increases to no more than 3% through 2026,” she said in a statement. She said the company has “adopted companywide savings initiatives to reduce our operating costs and limit unnecessary expenses” and is “supporting customers with ways to reduce energy use and bills.”

The second legislative proposal, Assembly Bill 3264, would require the Public Utilities Commission to study how to reduce costs of expanding transmission capacity and report to the Legislature on energy efficiency programs funded through consumers’ utility bills.

Two other Senate bills are aimed at consumer utility costs. Senate Bill 1003 would help address the cost of utilities’ wildfire plans, advocates said, and Senate Bill 1142 would prevent power shutoffs for consumers who agree to payment plans.

“It feels more like a political stunt and it’s unconscionable we would do that to our children, our staff members and our teachers.”

— Stephanie Seidmon, UndauntedK12

The Senate moved forward with a considerably scaled-back version of proposals to fast-track renewable energy projects. Those proposals aimed to streamline and assist solar, offshore wind, battery storage and other green energy projects.

Senate Bill 1272 would allow the California Energy Commission to adopt an overall environmental impact report that evaluates the potential effects common to a wide range of clean energy projects. The approach allows developers in most cases to rely on that analysis, saving time and money.

Renewable energy advocates asked for more time to craft better legislation given the bill “raises more questions than it answers.”

Instead, the clean energy groups wanted the state to update its tax code to align with federal rules that would allow them to take advantage of renewable energy tax credits that are part of the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act, without being taxed on them as income.

“We appreciate the intent to facilitate project streamlining, which is definitely needed, but deserves more discussion,” Shannon Eddy, executive director of the Large-scale Solar Association, told CalMatters. “What clean energy projects need in that timeframe is tax conformity.”

McGuire backed away from proposals that would create the tax credits, streamline local and state permitting and grant “by right” approval to developers building in areas already zoned for them, which would eliminate the need for local approvals, according to a previous CalMatters report.

Also gone are proposals to consolidate the process by creating a “one-stop shop” system that would consolidate applications, hearings and decision-making.

McGuire told CalMatters that creating tax credits was difficult given the state’s large fiscal deficit. He said he would bring back the rest of the measures next year.

To meet its ambitious greenhouse gas targets, California must supply 60% of its energy from renewable sources by 2030 and 100% by 2045. Californians are facing the highest energy bills in continental America.

Another proposed measure, Senate Bill 1420, would allow hydrogen-producing facilities to benefit from some streamlining under the California Environmental Quality Act. One environmental group, California Environmental Voters, said they would oppose the measure because it could open the door to hydrogen facilities powered by fossil fuels getting expedited.

It was not clear Thursday whether any of the measures would come to a vote by Saturday — or whether they would pass — given tense negotiations and competing priorities of legislators.Newsom warned legislative leaders he would call a special session to address energy issues unless Senate Bill 950 aimed at gas prices was passed — a prospect the state Senate’s leader, McGuire, publicly opposed. A spokesperson for Speaker Assembly Robert Rivas declined to comment.

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.