California’s New Senate Leader Wants Democrats United. A Budget Shortfall Could Divide Them

Maya C. Miller / Wednesday, Jan. 7 @ 7:25 a.m. / Sacramento

Senate President Pro Tem Monique Limón addresses lawmakers during her swearing-in ceremony in the Senate chambers at the state Capitol in Sacramento on Jan. 5, 2026. Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters/Pool

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

As California legislators return to Sacramento and prepare to tackle a budget deficit, all eyes are on new Senate President Pro Tem Monique Limón of Santa Barbara and what tone she sets for her chamber.

Limón, 46, a progressive backed by labor unions and the first Latina to lead the Senate, will face arguably her greatest legislative challenge yet as she and her diverse caucus grapple with a daunting projected $18 billion state budget deficit and historic federal funding cuts from the Trump administration.

While Limón has yet to announce any cost-cutting strategies or impose any limits on lawmakers introducing bills that require new money, the scarcity of funds will likely force the new leader to focus on a few key priorities, a premise she resisted in a recent interview with CalMatters.

“Our caucus will continue to prioritize issues that our communities prioritize,” Limón said, rattling off a laundry list of policy areas including access to health care, cost of living, education, housing affordability and child care. The new Senate leader also emphasized the importance of finding policy solutions that are “encompassing of our caucus — that reflect 58 counties, 483 cities.”

But how she’ll do that, while keeping the budget under control, remains to be seen.

For Limón, who has developed a reputation as an egalitarian consensus builder who wants everyone to feel heard, whittling down those priorities will test her ability to say “no” as the caucus tries to both rein in spending and fund programs that help vulnerable Californians.

She told reporters at the Capitol on Monday that she expects senators to understand that “spending big is not something that is within our means at this moment” and said she would reiterate that message at their first caucus meeting.

Colleagues past and present give her their vote of confidence to lead the chamber through a difficult budget year.

“She’s a good person to have in place when there’s a challenge,” said Kate Parker, who served alongside Limón on the Santa Barbara school board, including as president. “Obviously the budget is going to be horrendous, and she’s somebody that I would really trust to move the state forward in a really difficult time.”

From school board to Senate leader

Limón points to her nine-year tenure in the Legislature and relationships with legislative colleagues as the foundation for her inevitably tough conversations about how to prioritize a mountain of pressing issues.

The new Senate leader is best known for pursuing pay transparency legislation, consumer protections such as shielding medical debt from credit reports, and efforts to regulate the oil industry. She authored a 2022 law that requires setbacks around new oil and gas wells and steps to protect residents who live near old wells, and pushed for an unsuccessful 2021 bill to ban oil fracking. Gov. Gavin Newsom later ordered the ban.

State Sen. President Pro Tem Monique Limón during a press conference with fellow California Democrats at the Capitol Annex Swing Space in Sacramento on Aug. 18, 2025. Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

In the Assembly she chaired the Banking and Finance committee and until recently led the Senate committee on natural resources and water. Under two former Senate leaders, Toni Atkins and Mike McGuire, Limón was second-in-command as majority leader for Senate Democrats and helped craft legislative strategy.

Limón was elected pro tem in June after joining forces with supporters of Sen. Angelique Ashby, a Sacramento Democrat also seeking the role, to amass a majority of the caucus and shut down a competing bid from Sen. Lena Gonzalez of Long Beach. The power jockeying came amid a chaotic week as a federal standoff over immigration enforcement exploded in Los Angeles and the Legislature scrambled to finalize a budget. Limón has since named Ashby as her majority leader.

Prior to running for the Legislature, Limón served six years on the board of trustees for the Santa Barbara Unified School District, the public school system she attended before she immersed herself in public service and policy studies at UC Berkeley and later, graduated from Columbia University with a master’s degree in education.

Her first election for public office came in 2009 when Limón ran for an open spot on the Santa Barbara school board. Former board president Kate Parker, who overlapped with Limón during the now-senator’s six-year tenure, said she had never heard of Limón before the election and was even a bit skeptical about her leadership ability.

“It was kind of out of left field that she was running, and she didn’t have a kid in the district,” said Parker. “She seemed so young to me at the time. You know, I think she was probably like 30 or something. And I just wasn’t sure if she had the experience to be a strong leader in the district.”

But from their first meeting, Limón impressed Parker with her ability to listen to all sides and draw consensus from a group with a wide range of opinions.

“She was really good at crafting productive compromise,” Parker said. “She had a policy of meeting with anybody that wanted to talk to her.”

Limón has been tight-lipped about how she’ll steer the caucus through budget negotiations. But Parker said Limón is no stranger to difficult spending discussions. Nearly every year they served together, the school board faced budget challenges.

“Her guiding principle, in that context, was always putting the student first,” Parker said, adding that Limón always tried to keep funding cuts as far away from the classroom as possible.

“I imagine that at the state level, you’ll find that she has guiding principles as well that help with her decision-making process,” Parker said. “It’s not random, it’s not piece by piece. It’s systematic.”

Limón has yet to divulge precisely what those guiding principles will be for the Senate under her leadership. In an interview with CalMatters, she declined to identify any specific legislative measures that the caucus would prioritize.

But she hasn’t ruled anything out, either. When asked specifically whether her caucus should consider raising taxes or cutting state services, Limón didn’t reject either idea, both considered politically radioactive options.

“Everything’s on the table until we choose, or make a decision that it shouldn’t be on the table,” Limón said. “But having a deliberative and thoughtful conversation about the options in front of us doesn’t mean that we necessarily move forward with all options. It just means that you consider them.”

No bad blood with McGuire

Limón’s reputation as a collaborator and consensus builder contrasts starkly with that of her predecessor, McGuire, who some members, staff and lobbyists have privately called a micromanager.

During last year’s eleventh-hour negotiations over reauthorizing the state’s cap-and-trade program, McGuire reportedly kept the Senate’s draft bill language under lock and key and refused to let members take copies with them to review with staff, instead requiring them to come in person to view the text and banning photos. Advocates said they felt iced out of discussions and had little to no opportunity to give input.

“We are hopeful that this change in leadership means the beginning of a new and more transparent process,” said Asha Sharma, state policy manager for the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability.

Frustrations boiled over in a September budget subcommittee hearing when lawmakers debated a budget bill that contained more than $85 million in earmarks for projects in McGuire’s northern coastal district. That power play prompted Democratic Napa Sen. Chris Cabaldon to quip in front of the whole committee, “There are more than just a handful of disadvantaged communities, plus the North Coast, in California.”

Limón has tried to tamp down any criticism of her predecessor.

State Sen. Monique Limón prior to being sworn in as Senate president pro tem in the Senate chambers at the state Capitol in Sacramento on Jan. 5, 2026. Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters/Pool

“There was never a moment that this was a comparison of leadership,” Limón insisted. “At the end of the day, this is really about what the caucus wants, the direction the caucus wants to go, the experiences that the caucus feels are needed at this moment in time.”

Limón led the Senate’s working group on the reauthorization of the state’s cap and trade program, a fight at the heart of negotiations on a climate and energy policy deal that dragged out the final days of last year’s legislative session.

Her greatest challenge, said Sen. John Laird, a Santa Cruz Democrat and fellow member of the working group who she has named as her budget chair, was bridging the gaps between members who wanted to maintain the existing cap-and-trade program largely as-is and the climate hawks, who wanted to ditch some of the concessions former Gov. Jerry Brown gave to polluting industries to win votes during the last reauthorization.

“That was a real test because that was like riding a f-ing bronco,” Laird said. “And yet she worked hard to hold the Senate together. She worked hard to understand what individuals really wanted. And a lot of what we desired was part of the final results because of her work.”

BOOKED

Today: 6 felonies, 7 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

No current incidents

ELSEWHERE

Governor’s Office: Governor Newsom announces appointments 1.13.2026

County of Humboldt Meetings: Humboldt County Behavioral Health Board Meeting - Jan. 22, 2025

This Change Could Deliver Billions of More Dollars to California Schools. Here’s the Tradeoff

Carolyn Jones / Wednesday, Jan. 7 @ 7:20 a.m. / Sacramento

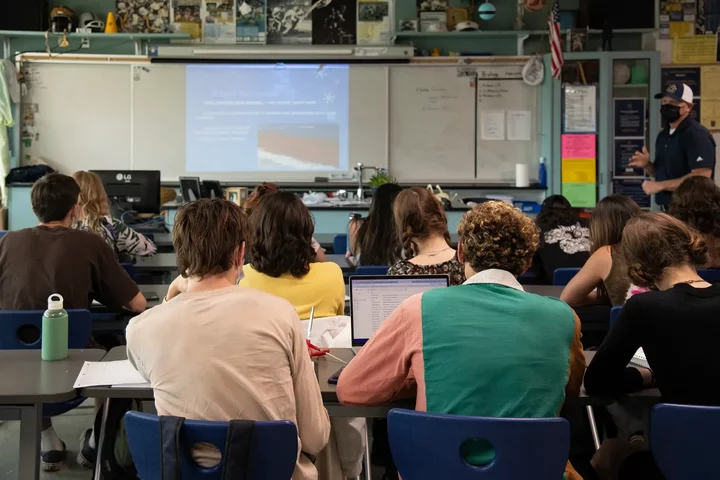

Students in a classroom at a high school in California on March 1, 2022. Photo by Salgu Wissmath for CalMatters

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

For years, California schools have pushed to change the way the state pays for K-12 education: by basing funding on enrollment, instead of attendance. That’s the way 45 other states do it, and it would mean an extra $6 billion annually in school coffers.

But such a move might cause more harm than good in the long run, because linking funding to enrollment means schools have little incentive to lure students to class every day, according to a report released Tuesday by the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office. Without that incentive, attendance would drop, and students would suffer.

If the Legislature wants to boost school funding, analysts argued, it should use the existing attendance-based model and funnel more money to schools with high numbers of low-income students, students in foster care and English learners.

When it comes to attendance, money talks, the report noted. For more than a century, California has funded schools based on average daily attendance – how many students show up every day. In the 1980s and ’90s, the state started to look at alternatives. A pilot study from that time period showed that attendance at high schools rose 5.4% and attendance at elementary schools rose 3.1% when those schools had a financial incentive to boost attendance.

This is not the time to ease up on attendance matters, the report said. Although attendance has improved somewhat since campuses closed during the pandemic, it remains well below pre-COVID-19 levels. In 2019, nearly 96% of students showed up to school every day. The number dropped to about 90% during COVID-19, when most schools switched to remote learning, but still remains about 2 percentage points below its previous high.

Attendance is tied to a host of student success measurements. Students with strong attendance tend to have higher test scores, higher levels of reading proficiency and higher graduation rates.

“It’s a thoughtful analysis that weighs the pros and cons,” said Hedy Chang, president of the nonprofit research and advocacy organization Attendance Works. “For some districts there might be benefits to a funding switch, but it also helps when districts have a concrete incentive for encouraging kids to show up.”

True cost of educating kids

Schools have long asked the Legislature to change the funding formula, which they say doesn’t cover the actual costs of educating students, especially those with high needs. The issue came up repeatedly at a recent conference of the California School Boards Association, and there’s been at least one recent bill that addressed the issue.

The bill, by former Sen. Anthony Portantino, a Democrat from the La Cañada Flintridge area, initially called for a change to the funding formula, but the final version merely asked the Legislative Analyst’s Office to study the issue. The bill passed in 2024.

A 2022 report by Policy Analysis for California Education also noted the risks of removing schools’ financial incentive to prioritize attendance. But it also said that increasing school funding overall would give districts more stability.

Enrollment is a better funding metric because schools have to plan for the number of students who sign up, not the number who show up, said Troy Flint, spokesman for the California School Boards Association.

He also noted that schools with higher rates of absenteeism also tend to have higher numbers of students who need extra help, such as English learners, migrant students and low-income students. Tying funding to daily attendance — which in some districts is as low as 60% — brings less money to those schools, ultimately hurting the students who need the most assistance, he said.

“It just compounds the problem, creating a vicious cycle,” Flint said.

To really boost attendance, schools need extra funding to serve those students.

Switching to an enrollment-based funding model would increase K-12 funding by more than $6 billion, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office. Currently, schools receive about $15,000 annually per student through the state’s main funding mechanism, the Local Control Funding Formula, with an additional $7,000 coming from the federal government, block grants, lottery money, special education funds and other sources. Overall, California spent more than $100 billion on schools last year, according to the Legislative Analyst.

Motivated by money?

Flint’s group also questioned whether schools are solely motivated by money to entice students to class.

“Most people in education desperately want kids in class every day,” Flint said. “These are some of the most dedicated, motivated people I’ve met, and they care greatly about students’ welfare.”

Josh Schultz, superintendent of the Napa County Office of Education, agreed. Napa schools that are funded through attendance actually have lower attendance than schools that are considered “basic aid,” and funded through local property taxes. Both types of schools have high numbers of English learners and migrant students.

“I can understand the logic (of the LAO’s assertion) but I don’t know if it bears out in reality, at least here,” Schultz said. “Both kinds of schools see great value in having kids show up to school every day.”

OBITUARY: Candace Miller, 1947-2025

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Jan. 7 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Candace Miller, born June 20, 1947, to Martha and Guido Canclini, passed away peacefully on December 25, 2025, after being diagnosed with Lewy Body Dementia in 2020. Candy spent her entire life in Humboldt County, attending grade school at Jacoby Creek School and graduating from Arcata High School in 1965.

She had many fond memories of her early days growing up in Sunnybrae, where she met some of her lifelong friends. She was a cheerleader at Arcata High School and was named Homecoming Queen in 1964. Many people will remember seeing Candy working alongside her parents at the Plaza Shoe Shop, located on the Arcata Plaza.

After high school, Candy attended College of the Redwoods, where she enrolled in as many art classes as she could. She had a passion for the arts and remained an artist her entire life. She began her artistic journey as a fiber artist, always loving texture and form, and grew increasingly excited by turning small knots into large sculptural wall hangings, otherwise known as macramé. She was also an active member of the Arcata Chamber of Commerce.

In 1967, she married Robert Miller, and together they welcomed their son, Tad Miller, in 1970. They lived in Jacoby Creek, just down the road from Candy’s parents. They later divorced in 1987, but remained friends until Robert’s death in 2020.

In 1979, Candy noticed an advertisement for “Fimo” clay in a magazine and decided to try this so-called “new” clay. She purchased several blocks at a local art supply store and immediately loved that it came in vibrant colors, was inexpensive, and traveled well. Many will remember that she began by making whimsical little lizard pins to wear. Encouraged to enter them in a local craft fair, she made 24 lizards—and sold every one. From that little “lizard beginning,” she went on to create thousands of brooches, earrings, necklaces, and buttons. She covered tin boxes with polymer clay, made clay collages, and ended her career sculpting. Candy could always be seen at holiday art fairs with her beautiful display of Fimo jewelry. She was a longtime member of the Arcata Artisans, where her jewelry was displayed for all to enjoy. Over the years, she experienced many proud moments, receiving numerous awards for her work.

Candy truly loved living on the Arcata Plaza. She enjoyed walks around town, frequenting the farmers markets, and especially looked forward to her walks at the Arcata Marsh and Wildlife Sanctuary. She was a longtime employee at Murphy’s in Sunnybrae, where she was often seen at Register 1. She enjoyed meeting families, watching their children grow, and being a helpful hand in any way she could.

Candy’s fondest memories were the many weekends spent at the family cabin on the South Fork of the Trinity River. There, she enjoyed days by the river—moving and skipping rocks, building paths, and sharing long conversations on the deck overlooking the water with family and friends. After the arrival of her two granddaughters, Sydney and Grace, she took on the yearly planning of elaborate Easter egg hunts for everyone to enjoy. In her spare time, Candy loved teaching Sydney and Grace how to make Fimo clay art and supporting them in all their endeavors.Candy was preceded in death by her parents, Guido and Martha Canclini. She is survived by her brother, Peter Canclini; her son, Tad Miller; daughter-in-law, Kelly Miller; and her two grandchildren, Sydney Hill (Miller) and her husband, Brock Hill, and Grace Miller.

A memorial service for Candy will be held on Saturday, January 17, at 11 a.m. at the Baywood Country Club. All are welcome. The family would also like to extend their heartfelt thanks to the staff at Renaissance of Timber Ridge in McKinleyville for the care and love shown to Candy. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to the Humboldt Historical Society or Miranda’s Rescue.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Candy Miller’s family. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

OBITUARY: Thomas Emil Eggel, 1946-2025

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Jan. 7 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Thomas Emil Eggel of 357 Regli Lane, Ferndale, passed away on December 11, 2025 on his brother’s Ferndale ranch on Crosby Lane. He was 79.

Tom was born to Olga and Emil Eggel on May 9, 1946 in Arcata. He was raised in Klamath, Orick and Arcata. He graduated from Arcata High School in 1964 and was drafted into the military in 1965. After serving, he went to work in the Arcata Plywood plant until it closed its doors. Tom moved to Ferndale in the early 1980s to start a dairy ranch, which he maintained until 1989. He then went to work for Eel River Disposal in Fortuna until he retired.

After retirement, Tom enjoyed his time working on the ranch property he inherited from his uncle Ed Regli. He spent many days and hours improving the roads and the family campsite on the property that he loved so much.

Tom is survived by his wife Lucia and stepsons, Zanden, Hero and Prince in addition to his son L.T. with his deceased wife Lovelyn. He also is survived by his first wife, Charlotte Palmer, their children Tony (Shannon) Eggel and Annette Eggel (James) Carpenter and grandson Calvin Carpenter, along with several nieces and nephews, and his brother Robert Eggel.

He was preceded in death by his parents, brother Jim Eggel, sister Kay Eggel Schekla, sister Mary Eggel Pelasini and his second wife Lovelyn Delogosa.

There will be a memorial mass held on January 10, 2026 at 1:30 p.m. at Assumption Catholic Church at 546 Berding in Ferndale, with a potluck gathering in the church hall following the service.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Tom Eggel’s family. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

OBITUARY: Paul Calvin Windham, MD, 1949-2025

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Jan. 7 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Paul Calvin Windham, MD, passed into eternal rest on December 13, 2025, at the age of 76, following a courageous two-year battle with cancer.

Born on September 13, 1949, in Poteau, Oklahoma, to Avis Ruth Garner and Calvin Raleigh, Paul moved with his family to California as a young boy. He graduated from Blackford High School in San Jose in 1967. While working his first job at Century Theaters, he met Kathleen Littmann, the love of his life. The couple married on June 29, 1968, at St. Martin’s Church in San Jose, beginning a devoted partnership that would span 57 years.

In 1972, Paul and Kathleen relocated to Central Oregon, hoping to build a career with the U.S. Forest Service. When only seasonal positions were available, Paul returned to school, earning an associate’s degree at Central Oregon Community College before transferring to the University of Oregon. There he graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1977 with a Bachelor of Science in Molecular Biology. That fall, he entered Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland, receiving his Doctor of Medicine in 1981. He completed his internship in Spokane, Washington.

During these demanding years of education, Kathleen’s steadfast support kept the family afloat. Their children arrived along the way: son Jason Matthew in Bend, Oregon; son Adam Taylor in Portland; and daughter Elizabeth Ann in Spokane during Paul’s internship.

Summers found Paul working fire control and recreation for the U.S. Forest Service on the Willamette National Forest. Four of those seasons were spent living remotely at the Taylor Burn wilderness guard station, reachable only by a 10-mile dirt road. These profound experiences in Oregon’s wild places deeply influenced his choice of Emergency Medicine as a specialty. Later, his ER expertise provided a natural transition into Occupational Medicine. For a time after Elizabeth’s birth, he served as a medical officer with the U.S. Public Health Service at a clinic on the Taholah Indian Reservation in coastal Washington.

A man of wide-ranging passions, Paul was a voracious reader and ardent football fan. He rode a Harley, loved music and delighted in exploring philosophy, theology, history, astronomy and biology.

Faith was central to Paul’s life. He entered the Catholic Church at Easter 1993 at Our Lady of Mercy in Merced, California. A devoted Fourth Degree Knight of Columbus, he held several leadership roles, including Faithful Navigator and Grand Knight. In Merced, he and Kathleen taught RCIA and CCD classes. Paul also served as an adult altar server, Eucharistic minister and, more recently, a lector.

A Mass of Christian Burial will be celebrated on January 10, 2026, at St. Bernard Church in Eureka, preceded by a rosary at 9:30 a.m. and the Mass at 10 a.m., followed by a reception at the church. Interment will take place at 2 p.m. at St. Bernard Cemetery.

Paul is survived by his beloved wife, Kathleen; sons Jason Matthew (Crystal) and Adam Taylor (Sherezada); daughter Elizabeth Ann (Josh)Wolf; grandchildren Nicodemus, Heidi, Rachel, Cole, Vincent and Julian; great-granddaughter Lily Windham; and sisters Beverly York and Lisa Raleigh.

In lieu of flowers, memorial contributions may be made to St. Bernard Church (designated for maintenance) or to the Betty Kwan Chinn Homeless Foundation.

Paul’s life was marked by dedication — to his family, his patients, his faith and the natural world he cherished. He will be deeply missed and fondly remembered.

###

The obituary above was submitted by Paul Windham’s family. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

Lots of Unknowns for Jan. 2 Arcata Fire Cleanup Efforts

Dezmond Remington / Tuesday, Jan. 6 @ 4 p.m. / Fire , Government

The building ablaze. Photo by Ryan Burns.

The pile of rubble sitting on the corner of 10th and H streets in Arcata probably won’t be going anywhere tomorrow.

The Jan. 2 fire that destroyed seven local businesses and displaced about as many people reduced half a city block to a steaming pile of brick and timber. None of it has been cleaned up yet. Arcata’s city manager, Merritt Perry, told the Outpost during a phone call today that the property owner, their insurers, and the city are working together to clean the site up as quickly as possible. Though cleanup is the owner’s responsibility, he said Arcata would do “whatever we can” to support them, such as accelerating permit approvals and following up with outside entities.

Perry said the city will meet soon with the owner and their insurance agents to figure out a cleanup plan and timeline. The owner will need to assess the kinds of debris on-site and may need a certified hazardous materials contractor to haul it away.

The fire also likely damaged the environment; to what extent is unknown. Ash and the chemicals released by burning buildings is toxic enough on its own, but the fire also burned the paint section of Hensel’s Ace Hardware, and some of it was probably washed down storm drains and into Humboldt Bay when the firefighting crews were trying to put the fire out. The runoff could negatively impact the bay and other aquatic wildlife habitats.

Arcata Director of Community Services Emily Sinkhorn told the Outpost that they were monitoring water quality at drains around the burned lot and had also installed devices that stop water from entering. Staff are also keeping an eye on creeks downstream for fire debris.

A city spokesperson said that they were partnering with outside agencies like California’s water quality and toxic substances boards, California’s Environmental Protection Agency and the North Coast Unified Air Management Quality District.

Because neither Arcata nor Humboldt County has the resources to accurately measure and mitigate the effects, the sheriff’s office declared a local state of emergency yesterday, allowing them to request funding from the state of California. How much they’ll need is unknown.

The spokesperson said there would be a special city council meeting at 8 a.m. this Friday on Zoom with more details about the fire and cleanup. The agenda isn’t public yet.

“The thing I would like to emphasize is that we’re not just ignoring it,” Perry said. “We’re taking a very active approach, and that’s why we did the emergency declaration — to bring the resources in that we need to assess and mitigate any contamination.”

In Daryl Jones Prelim Hearing, Cops Recount Graphic Threats to Harm and Kill Children at Local Schools

Ryan Burns / Tuesday, Jan. 6 @ 2:29 p.m. / Courts

File photo.

###

PREVIOUSLY

- Multiple Humboldt County Schools Placed on Lockdown Due to Threats

- LOCKDOWNS UPDATE: Out-of-State Man Identified as Suspect Believed to Have Made Threatening Calls to Multiple Humboldt Schools and Businesses

- Extradition Arrest Warrant Issued for Out-of-State Asshole Who Keeps Threatening Local Schools

- 31-Year-Old Oklahoma Resident Arrested on Multiple Felony Counts for Making ‘Terrorist Threats’ to Local Schools

- Officers Recount Threatening Phone Calls to Schools During Preliminary Hearing in Trial of Daryl Jones

- We’ll Have to Wait Until October to Finish the Prelim Hearing for Man Charged With Threatening Schools, Businesses

###

WARNING: This story includes descriptions of testimony that readers will almost certainly find disturbing.

###

In the long-delayed resumption of a preliminary hearing for Daryl Ray Jones, officers from both the Arcata and Fortuna police departments took the stand this week to recount a series of threatening phone calls made to local businesses and schools last winter.

Jones, who faces multiple felony counts of making terroristic threats, sat silently at the defense table throughout the days’ testimony, wearing a white dress shirt. Whenever he leaned forward, the shirt pulled tight across his shoulders and the “3XL” printed on the back of his inmate jumpsuit was legible through the thin fabric.

In their testimony, officers described numerous phone calls in which a male voice threatened to commit violent acts. In at least one case, the caller expressed a desire to rape, kill and mutilate children.

The threats, made from several different phone numbers in late February and March of 2025, prompted lockdowns at several local schools and preschools. Under questioning from Deputy District Attorney Roger Rees, the lead prosecutor in the case, officers said the calls sparked fear in business employees, school secretaries, administrators and others.

Jones is being represented by Meagan O’Connell with the county’s Conflict Counsel Office. In cross-examining the officers, she questioned whether they could be certain about specific details, often challenging their assertions that the people who answered these calls found the threats credible and were scared by them.

Fortuna Police Officer Bryce Sancho testified about threatening calls made to that city’s Starbucks and Trish’s Out of the Way Café. The caller made “nonstop calls threatening to kill everyone inside” the latter establishment, Sancho said.

Fortuna Police Detective Thomas Macleod testified about responding to Rainbow Junction Children’s Center, a Fortuna preschool and daycare that was put on lockdown after receiving multiple calls from a man who threatened to shoot up the school.

The most explicitly violent threats recounted in court thus far were made during a call to Jacoby Creek Elementary School on March 19. Arcata Police Officer Robert Duggan testified that a school secretary there answered the phone and spoke to a man who said he planned to “kill you and all of the children I can get my hands on.”

The caller went on to say he wanted to “slit all of the children’s throats” and “really wants to rape all the little girls, cut their backs open and peel the skin off so he can see their ribs,” Duggan testified. The secretary was afraid that the caller could be across the street, and after she told the school principal about the call, a shelter-in-place was ordered.

Death threats were also called in to Fuente Nueva Elementary School that same day, and the school was placed on lockdown, according to testimony from Arcata Police Sergeant Abraham Jansen.

The next day, March 20, a secretary at Sunny Brae answered a call from a man who said, “I’m going to kill you and all the children in the school,” according to Duggan’s testimony. While most of the threatening calls had been made from cell phones with a 707 area code, this one came from the Oklahoma-based area code of 580, Duggan said. Jones has history in Humboldt County but was living in Oklahoma at the time of his arrest.

Other officers testified to threats called in to yet more schools, including Arcata Elementary School, Pacific Union Middle School and Coastal Grove Charter School.

Arcata Police Officer Kasey Burke testified that on March 20, she responded to Arcata Elementary and found staff crouched behind a desk in the administration office with the lights off. The school’s secretary had answered a from a man who addressed her by her first name and said, “I’m going to kill you, arrogant bitch,” Burke said.

When a call came in to Pacific Union the next day, Burke responded to the scene and managed to speak with the caller. By this point, the Arcata Police Department had identified Jones as a suspect, and so when a school secretary answered a call and promptly handed the phone over to Burke, the officer engaged the caller in conversation while addressing him as “Daryl.”

“Did the person correct you [or] indicate that wasn’t their name?” Rees asked.

“No,” Burke replied.

During the phone conversation with Burke, the caller said he wanted to rape children. Burke testified that he told the caller this wasn’t a wise decision, but the caller reiterated his desire to rape children. When Burke asked him why, the caller said it was “because he was sad,” the officer testified. Under cross-examination from O’Connell, Burke said the caller also admitted to being depressed.

While school employees may have been scared by these calls, Burke said he wasn’t.

“I believe that Daryl, the person I was talking to, was doing this in a manner to get attention, and probably, likely, mental health stuff was going on with him,” Burke said.

While Burke was on the Pacific Union campus, employees and administrators recounted their own conversations with the subject. Principal Mathew Bigham reported that the caller had expressed his intent to rape children and said, “little boy or little girl, don’t matter.”

In a call to Coastal Grove, the caller again said he planned to shoot and rape children and told a secretary, “I’m gonna shoot you; I’ll be there in 30 seconds,” Burke testified.

Officer testimony extended through the afternoon on Monday and resumed this morning, with other Arcata police officers relaying information about threatening calls made to the Best Western in Valley West, Humboldt Brews downtown and Arcata High School. These calls, made in late February, included more threats to harm and kill.

Jones was arrested on March 21 of last year. Legal proceedings against him were delayed after Judge Kelly Neel expressed doubt about Jones’s ability to understand the charges against him and participate in his own defense. Jones was subsequently examined by local clinical psychologist Dr. Mark Lamers, and the preliminary hearing began in August.

The preliminary hearing is intended to lay the groundwork for a jury trial. But that hearing was itself delayed after just a day and a half of testimony when Rees admitted that he had failed to turn over some important court documents to the defense counsel, O’Connell. He cited a filing mistake.

The preliminary hearing is scheduled to continue tomorrow.