HAPPY BIRTHDAY, AMERICA! Choose Your Own Humboldt Fourth of July Adventure With Our Handy Guide to Local Festivities!

Hank Sims / Monday, July 3, 2023 @ 8 a.m. / Event

Get hype for America Day!

Someday someone will tell me why Humboldt — a traditionally America-skeptical place — goes all-out for the Fourth of July, but go all out it does. As with most years, we have stuff going on all up and down the county for the holiday.

Having trouble deciding where to go and how to celebrate? Here’s a probably incomplete rundown.

I want to celebrate the Fourth of July on the Third of July.

Get down to Fortuna

tonight! Down in the Friendly City they’re doing the whole damn

thing a day early, and they’re doing it up in family-friendly style! We’re talking about clowns, balloon animals, a petting zoo and not one bounce house, not two bounce houses, nor yet three bounce houses … but FIFTEEN FRICKIN BOUNCE HOUSES.

When night falls, things start to get loose. At 8:30 p.m., the bounce houses and clowns and goats are swept into the corner and the dance party begins. We’re talking about a laser light show. We’re talking fire dancers. That goes on until 10 p.m., when the skies erupt in flame! They don’t call it the Fortuna Fireworks Festival for nothing!

The fun starts at 5:30 p.m. at Newburg Park. Admission is free, but you gotta shell out $10 for a kid’s wristband for what they promise to be “unlimited fun” for the tots.

Remember: This is all happening on July 3. More information at the FFF Facebook page.

I’ll take my Fourth on the Fourth, thank you, and I want the classic Northern Humboldt County block party with hordes of people and crafts and vendors and beer and live music from the bands that always play at those kinds of things. Preferably foggy.

Two flavors of that are available: The Eureka flavor and the Arcata flavor. They’re pretty close in spirit, but a connoisseur can no doubt list differences. Is it trading in stereotypes to say that the Eureka festival feels a bit more working-class and blue-collar, while the Arcata festival tends toward the bougie and ethereal? Eureka has fire truck rides. Arcata has West African drum classes. You feel me?

Whatever — you can easily shuttle back and forth between the two, provided you have a sober driver.

In Eureka, the party starts early — 10 a.m. — and runs ‘til 5 p.m.. It happens in Old Town, and most of the streets are shut down to vehicles. Things get going a little later — 11 a.m. — on the Arcata Plaza.

Both of these festivals will have food booths, beer booths, bands, games, craft vendors, etc., etc. A couple of side shows are worth noting, particularly a barbecue at the Arcata VFW Hall at noon (more info), a Crabs game against the Solano Mudcats at 2:30 p.m., and speeder rides along the tracks on the Eureka waterfront most of the day (more info).

The biggest difference, of course: Fireworks. The fireworks take place in Eureka at 10 p.m., over the bay. Arrive early to secure a sweet spot on the Boardwalk.

Here’s more information on Eureka’s festival. Here’s more information on Arcata’s festival.

Parties are fine and dandy, I guess, but it’s not Fourth of July without a parade.

Two words: Fern. Dale.

You didn’t think that Humboldt County’s most self-consciously small town was going to let the nation’s birthday pass without slathering on the Americana, did you?

The parade — “fire trucks and patriotic floats and vehicles” — starts at noon and runs along Main Street. There’s a community barbecue at the VFW Hall from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. More information here.

I’m not going north, and America’s not my jam. I only pledge allegiance to Southern Humboldt.

Bro. Bro. You and your bros and all your extended clans are gonna meet up in Garberville, OK? The party happens from noon to 5 p.m. at Town Square, and in addition to the usual crafts and food trucks and kids’ activities it’ll feature a performance from Irie Rockers.

BOOKED

Today: 9 felonies, 13 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Yesterday

CHP REPORTS

76699 Sr162 (HM office): Trfc Collision-1141 Enrt

ELSEWHERE

Governor’s Office: Governor Newsom announces deployment of California resources to the East Coast ahead of multiple Atlantic storms

Times-Standard : Civic calendar | Arcata to discuss ‘threat to public services or facilities’

RHBB: State Cannabis Tax Cut a Mixed Bag for Humboldt (Also more Info from the Board of Supes)

RHBB: Mendocino County DA Fights Back as Recall Campaign Intensifies

A California City Was Making a Difference on Homelessness. Then the Money Ran Out

Marisa Kendall / Monday, July 3, 2023 @ 7:23 a.m. / Sacramento

A new homeless outreach program pairing a social worker with a police officer in Grass Valley, a small town in the Sierra Nevada foothills, seemed to be working.

The state-funded effort sent the team to homeless encampments, where they helped build trust among vulnerable people and persuaded them to accept help, according to nonprofit Hospitality House, which ran the program.

It blew past its goal of engaging 90 people in three years, instead meeting with more than 200. It even helped move some people directly into housing, including an 80-year-old veteran.

But when the three-year grant paying for that outreach ended in June, there was no money to replace it. So the program came to a screeching halt, to the disappointment of all involved.

“It is a profound loss to not be able to do this,” said Nancy Baglietto, executive director of Hospitality House.

That loss embodies the worst fears of homeless service providers across California, as they struggle to piece together new funding sources after their state grants expire. Many had hoped that Gov. Gavin Newsom and legislative leaders would change that dynamic in the state budget deal they announced last week by committing ongoing funds for homelessness that nonprofits, cities and counties could rely on year after year.

It didn’t happen.

Instead, Newsom and lawmakers settled on another round of one-time funding.

“It really defies logic that the state budget once again fails to include funding to match the scale of the crisis we are experiencing,” said Carolyn Coleman, executive director and CEO of the League of California Cities, which pressed Newsom’s administration for a guaranteed $3 billion a year in homelessness funding.

‘Unprecedented’ homelessness funding under Newsom

As California grapples with how to provide for its massive population of more than 170,000 unhoused residents, Newsom has stepped up homelessness funding to unprecedented levels. He’s funneled nearly $21 billion into housing and homelessness since the 2018-19 fiscal year.

This year, for the third year in a row, the state budget allocates $1 billion to the Homeless Housing, Assistance and Prevention fund, which local officials can use for housing, outreach at encampments, emergency shelters and more.

But the vast majority of Newsom’s homelessness spending has been in one-time grants, which providers say makes it difficult to fund the kind of long-term programs that could make a noticeable dent in the crisis.

An encampment, in Los Angeles on June 20, 2023. Photo by Julie A. Hotz for CalMatters

California would need to spend $8.1 billion a year for a dozen years to eliminate homelessness in the state, according to a report by the Corporation for Supportive Housing and the California Housing Partnership, two nonprofit advocacy groups.

The governor’s office defended this approach to funding homelessness, pointing out that the state has provided an “unprecedented” $15.3 billion for the issue since he took office at the start of 2019. The governor has also proposed a 2024 ballot measure to amend the Mental Health Services Act that would provide $1 billion a year for housing for people with mental illnesses and substance abuse disorders. That amendment would require voter approval to take effect.

“This budget provides not just funding to address homelessness — it builds in the accountability needed to ensure that tax dollars are being maximized to produce real results,” Daniel Lopez, Newsom’s deputy communications director, said in an emailed statement. “Ultimately, the challenge of homelessness and housing must be met not only with dollars, but it also requires strong accountability coupled with financial resources to make lasting progress for our state.”

To be eligible for homelessness funding under this budget, cities and counties must submit homeless action plans — in coordination with other jurisdictions in their region — that detail the progress they’ve made.

Short-term homeless services

There was some momentum this year to move away from one-time spending on homelessness. More than two dozen state legislators signed a letter in May supporting the League of California Cities’ demand for $3 billion a year. A coalition led by the California State Association of Counties also called for ongoing funds and drafted bill language it urged legislators to adopt.

But that proved to be a tough ask with Newsom’s office projecting a $30 billion-plus budget deficit.

For years, city and county leaders, legislators and homelessness nonprofits have been clamoring for a source of ongoing funding to tackle the homelessness crisis. Assemblymember Luz Rivas, a Democrat from Arleta, pushed a bill in 2021 that would have established ongoing homelessness funding by raising taxes on large businesses, but the bill died without making it out of the Assembly. Last year, California voters rejected a ballot measure to legalize sports betting, which would have directed fees and taxes from those wages into a fund for homelessness.

Baglietto, of Hospitality House, says that type of permanent funding could have helped save her organization’s Grass Valley outreach program.

“We don’t know each year where the funding is going to come from. It’s kind of a nail-biting scenario.”

— Nancy Baglietto, executive director of Hospitality House

Hospitality House and the Grass Valley Police Department received $575,000 in 2020 through a state violence intervention program. The city put the money toward homeless outreach as a way to prevent unhoused people from experiencing violence in encampments, and also to reduce confrontations between police and unhoused people. By the time the grant ran out this year, Grass Valley’s crime rate had improved and the city was no longer eligible for the money, Baglietto said.

It wasn’t the first time the nonprofit was forced to scramble because of unreliable state funding. Hospitality House’s 65-bed homeless shelter once largely was funded by the state grants. Several years ago, the state changed how that money was allocated — focusing on permanent housing instead of shelter — and Hospitality House’s portion dried up. So the nonprofit cobbled together funding from a dozen different sources to fill the hole left by the state money, Baglietto said.

Now, Hospitality House keeps its shelter open through money from CalAIM, Newsom’s recent Medi-Cal expansion. The nonprofit still has a “massive” gap, which it is temporarily filling with federal COVID funds designed to help businesses retain employees. That money runs out next year.

“We don’t know each year where the funding is going to come from,” Baglietto said. “It’s kind of a nail-biting scenario.”

‘Havoc’ for California nonprofits

Union Station Homeless Services, which coordinates programs throughout the San Gabriel Valley in Los Angeles County, faces the same issues, said CEO Anne Miskey. Every budget cycle, her team has to spend two or three months piecing together their financing as the funding they get from the state changes or ends. Sometimes, the parameters for a state grant shift, and clients Union Station has been working with for years suddenly are no longer eligible.

“This is just creating havoc in our sector,” Miskey said. “And this is why people are leaving. It’s not the clients. It’s not the work. It’s this piece.”

The new state budget has some new language around homelessness funding. It requires that anyone applying for a grant be part of a regional plan that lays out the specific roles and responsibilities of each participant. That was something the California State Association of Counties pushed for, arguing that currently cities, counties and other groups too often fight over who should be building shelters, offering mental health help or providing other homeless services.

The budget also promises that it is the Legislature’s “intent” to provide additional the same funding in the 2024-25 fiscal year.

That’s not enough, said Graham Knaus, CEO of the California State Association of Counties.

“Counties cannot budget based on legislative intent,” he said. “Nobody can. We certainly can’t make multi-year commitments based upon intent where there’s no clarity about what’s going to happen next year.”

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

ARCATA HOMICIDE: 36-Year-Old Fortuna Man Shot and Killed; APD Seeking Suspect

Andrew Goff / Sunday, July 2, 2023 @ 6:23 p.m. / Crime

UPDATE, MONDAY AFTERNOON:

On July 2, 2023, at 7:20am, the Arcata Police Department initiated a homicide investigation in the 5000 block of Boyd Road, for a male gunshot victim located deceased in the roadway. The decedent has been identified as 36-year-old former Fortuna resident, Joshua Paul Gephart, who has been living as transient in the Valley West area of Arcata.

APD Detectives are actively working leads and request anyone with information to contact their Investigations Unit, at 707-822-2428, or the APD Anonymous Crime Tipline, at 707-825-2588.

This press release is the extent of the information that is currently available for public release. When appropriate, additional information will be provided.

###

Arcata Police Department press release:

The Arcata Police Department is investigating a shooting homicide that occurred during the early morning hours of July 2, 2023, in the 5000 block of Boyd Road in Arcata. The decedent is a 36-year-old male Fortuna resident whose identification is pending notification of next of kin.

Preliminary investigation does not indicate an on-going threat to the general public. The suspect remains at large, and anyone with information is encouraged to contact the Arcata Police Department’s Investigations Unit, at 707-822-2424, or the APD anonymous Crime Tipline at 707-825-2588.

This press release is the extent of the information that is currently available for public release. When appropriate, additional information will be provided.

GROWING OLD UNGRACEFULLY: It’s the CO2, Stupid! (Earth’s Good Fortune)

Barry Evans / Sunday, July 2, 2023 @ 7 a.m. / Growing Old Ungracefully

Feeling lucky today? If you’re up for a spot of geology, I hope to convince you that you really are, you and the eight billion Homo sapiens, along with countless members of the other ten million or so other species, who make a living here. It could have been so different: Earth could have ended up like Mars, the nearby rocky planet not-too-dissimilar from our own that, at this point, appears to be lifeless. Why the disparity? Our good fortune results from plate tectonics, the mechanism that causes continents to move slowly-but-surely over Earth’s surface.

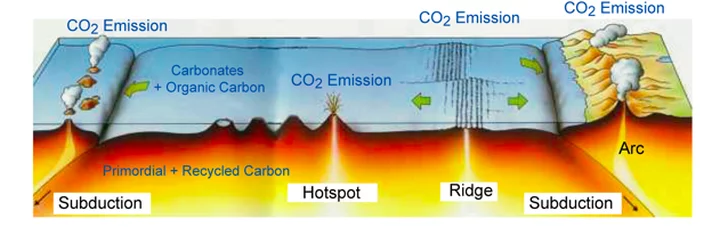

Earth has a hot core, hot enough to sustain a great ball of liquid iron in its interior. True, our planet is slowly getting colder, but Earth is large enough to have retained most of its original heat. Mars, with only one seventh the volume of Earth, lost most of its internal heat billions of years ago. Our internal heat is responsible for maintaining the plasticity of the mantle, the thick layer of material on which Earth’s crust literally floats. One result of continental drift is that the crust is constantly being recycled. For instance, the Pacific “plate” is being subducted under the North America (on which we in Humboldt sit, at the western edge) at a speed of a few inches per year. This recycling is responsible for the greenhouse effect, the sunlight-trapping process by which carbon dioxide in the atmosphere results in our warm climate.

Simplified greenhouse effect: visible light from the sun heats earth’s surface, which then radiates in infrared wavelengths. Carbon dioxide and water vapor allow incoming sunlight to pass through, but trap the infrared. (From Barry Evans’ The Wrong-Way Comet.)

Most planetologists believe that Mars also had a thick carbon dioxide “blanket” along with an ocean, but hat was three to four billion years ago. What happened? Mars’ problem is that carbon dioxide doesn’t just sit in the atmosphere, but is weathered out into carbonate rocks like limestone. To maintain an ongoing greenhouse effect, you need some way to return the gas from the rocks to the atmosphere. On Earth, the most significant process is our carbonate-silicate cycle, in which carbonate rocks are buried (subducted) deep below ground, where high temperatures and pressures melt them, releasing carbon dioxide.

Carbon dioxide outgassing through various processes, mainly volcanoes. (Benjilrm, Creative Commons License, via Wikimedia)

Eventually the thousand-plus active volcanoes here on Earth erupt the gas back into the atmosphere, and the cycle starts over. However on Mars, after a billion years or so of carbon dioxide recycling, the mechanism shut down because the planet’s interior had lost so much of its initial heat and it became too cold for volcanoes to function. With carbon dioxide trapped in the rocks instead of being returned to the atmosphere, the Martian air thinned. Without that carbon dioxide blanket to maintain its greenhouse effect, Mars slowly but surely froze. (True, it’s farther from the sun than we are, but those oceans lasted for a million or so years, even as the sun was maybe a third cooler than it is now.)

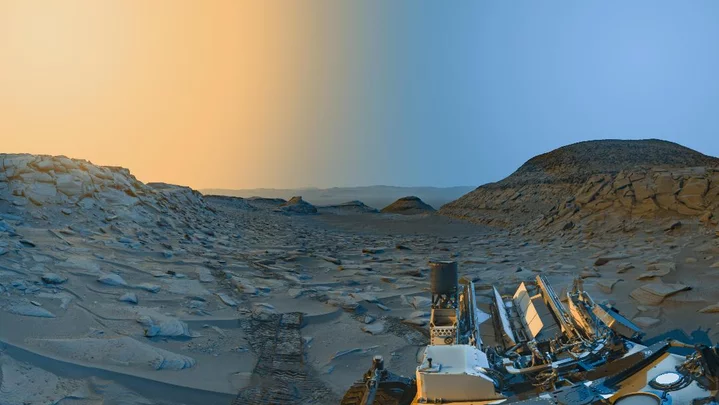

Mars seen through Curiosity’s mast camera: beautiful but probably lifeless. Blame the absence of plate tectonics. (JPL/NASA)

Here on Earth, the carbonate-silicate cycle keeps going thanks the interior heat that’s continually renewed through radioactive decay deep within the core. That heat drives our plate tectonic mechanism, causing the entire seabed to be recycled, fueling volcanic eruptions where plates slither past each other, returning CO2 to the atmosphere, maintaining Earth’s greenhouse effect. Hence we have liquid water in our oceans, and ubiquitous life…including curious, and lucky, humans who amuse themselves trying to figure out how it all works.

Two Hayfork Residents Killed in Solo-Vehicle Crash on State Route 3, CHP Reports

LoCO Staff / Saturday, July 1, 2023 @ 11:29 a.m. / News

Press release from the California Highway Patrol:

On June 30th, 2023, at approximately 1735 hours, a single vehicle collision occurred on SR-3, two miles north of SR-36, south of Hayfork. The driver was traveling northbound on SR-3, at an unknown speed, when the vehicle traveled off the road and collided into a tree. The driver and passenger, who were wearing their seatbelts at the time of the collision, sustained fatal injuries and were pronounced deceased at the scene. It is unknown if alcohol was a factor in this collision. The cause of the collision remains under investigation by the Trinity River Area CHP.

###

THE ECONEWS REPORT: Flow Enhancement Projects on the South Fork Eel

The EcoNews Report / Saturday, July 1, 2023 @ 10 a.m. / Environment

Redwood Creek. Photo: Katrina Nystrom, Salmonid Restoration Federation.

How

do you improve the flow of a river? Just ask our friends at Salmonid

Restoration Federation.

On this week’s episode of the EcoNews Report host Alicia Hamann of Friends of the Eel River is joined by Dana Stolzman and Katrina Nystrom from Salmonid Restoration Federation, and Joel Monschke from Stillwater Sciences, for a discussion of flow monitoring and enhancement projects on the South Fork Eel River. Tune in to learn more about SRF’s decade of flow monitoring on Redwood Creek, the Marshall Ranch Flow Enhancement Project, and more.

HUMBOLDT HISTORY: Growing Up in Crannell, the Lost Company Town Above the Banks of Little River

Weston Donald Walch / Saturday, July 1, 2023 @ 7:15 a.m. / History

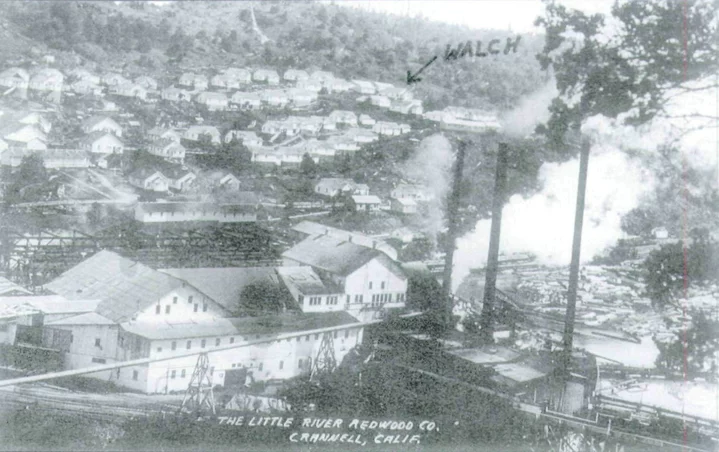

The bustling lumber town of Crannell, with the Walch house indicated. Photo courtesy Wes Walch, via the Humboldt Historian.

At the time of my birth, on December 10, 1928, to Weston and Mary Walch, a winter storm caused Little River to overflow its banks, flooding the valley and the road between Highway 101 and Crannell. My grandmother, Mae Fields, had driven up from Eureka in her high-wheeled Buick Roadster — the only car in our family — in order to take my mother to the hospital, but soon after her arrival at our home it became impossible to drive into or out of Crannell. The floodwaters were rushing over the road and the only way to get to Crannell was by the company railroad. Dr. Cooper, from Arcata, agreed to attend the delivery at our home, and my dad arranged with Mr. Heightman, the town boss, for an open-sided railroad car, or “speeder,” to bring Doctor Cooper into town. That was a cold and wet ride above the flooded road to Crannell. My mother was already in labor and Dr. Cooper arrived just in time for my birth. It was an adventure for the doctor to come as he did through the storm that night, and it seems it was an omen: my life was meant to be an adventure.

Crannell was a railroad logging “company town” owned by Hammond Lumber Company. The town was complete with family housing, bunkhouses and a lodge for the single workers, a cookhouse, company store, grammar school, church, a firemen’s dance hall and other facilities for the workers and their families. Crannell was located ten miles north of Arcata and two miles east of Highway 101 and Clam Beach. Little River coursed its way from the redwood-forested hills above Crannell, down beside town, then through the valley and the dairy-farm bottomlands, to flow into the ocean near Moonstone Beach.

Crannell on the map.

When I was born my parents already had three daughters. My dad had always been an outdoor person. He’d grown up on a ranch, he hunted, fished, and worked in the woods, and he wanted a boy. As told to me by my mother and grandmother, when my dad saw that I was a boy, he grabbed the doctor and danced with him on the kitchen floor. 1 had three older sisters, Belva (Dinah), Mae Pauline, and June Ann to dote over me, and I grew up in a very loving family.

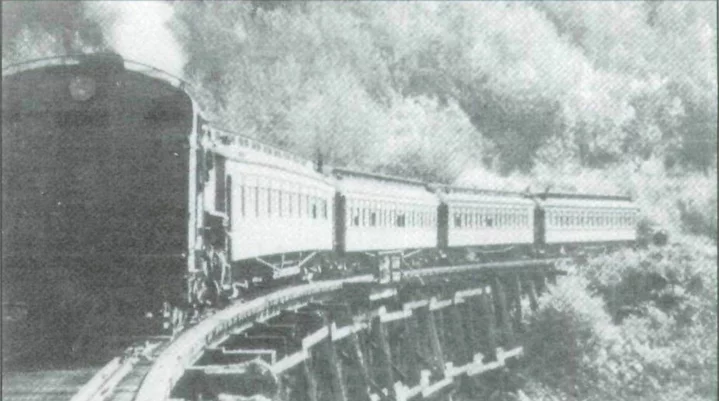

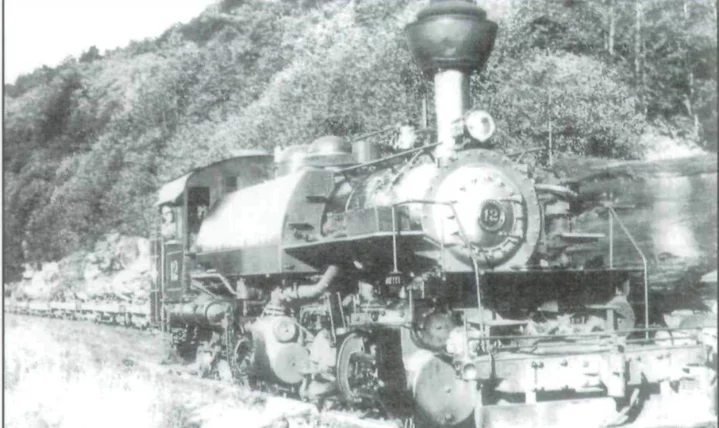

My very first memory in Crannell is of the train whistle each morning at five o’clock to awaken the workers for breakfast. After breakfast the loggers and woods crews would hike up the hill to the station and take the train into the woods for another day’s work. Ken Cole, or another of the Coles, was the engineer. The train would leave the roundhouse at Railroad Avenue and make its way up to Little River Junction, across the curved high trestle, and loop around to the upper, east side of Crannell, where we lived. The east side was called Hillside Terrace, and the lower, west side was called Eucalyptus Heights. Fancy names for this little town of Crannell! As the train neared the area above our house to pick up the crews, it would let out another whistle blast. Hiking from their homes to the station and back, the loggers cut deep trails with their caulk boots over the years, some more than a foot deep. Bachelor workers ran down to their cabins after work to be first to get hot water for a shower, and first in line for the dinner bell.

Passenger train hauling crews to the Hammond woods, 1930s. Photo courtesy Jack Trego, via the Humboldt Historian.

Our house on Hillside Terrace was the last house up the hill, not far from the upper tracks, and the steam whistle sounded like it was right outside our windows. We were close friends with the Cole family, and Ken Cole would always give a couple of toots above our house when he brought down another trainload of logs.

In addition to the passenger train, there were six other locomotives that pulled strings of flatcars to the woods. The caboose, with its potbellied stove, made a nice warm place for the crew to eat lunch or play cards while waiting in the woods for the flatcars to be loaded. Once loaded, the flatcars would be pulled to Crannell and left on a siding. A much larger locomotive would then pull two or three of them at a time out to the big company sawmill in Samoa. The railroad grade from Crannell to Samoa was mostly flat. It ran along the sand dunes of Clam Beach, over the Mad River railroad bridge, then on to the Samoa mill. Upon returning to Crannell the locomotives would be aligned in the roundhouse into proper work stalls by a large turntable. Night crews would apply oil and grease and make repairs, readying them for another day’s work. All day long during the work week, railroad trains were chugging and whistling past our house in Crannell.

I will always remember the sounds from these trains — the steam from the locomotives, the shrill whistles, the click-clack of the wheels on the rails and the screeching sounds of steel wheels against steel tracks when the trains rounded a curve. I can still recall the smell of the pungent black smoke belching from the stacks as the trains pulled hard up the railroad grades. These trains and the railroad were in use until the big 1945 fire in the Hammond logging woods near Big Lagoon, which burned down twenty-three bridges and destroyed much of the railroad.

Ken Cole with a load of logs for the Hammond mill at Samoa, 1930s. Photo courtesy Clearman Cole.

The beginning of my life coincided with the beginning the Great Depression. As everywhere. Depression times were tough in the timber industry. Due to the low demand for lumber to build houses, logging crews were working only a three or four-day week, and only one in three neighbors had work at all. My dad was fortunate to have mostly steady work during the Depression, as his job was operating a railroad steam crane. The high boom steam cranes were necessary to lift big timber beams to build the railroad bridges and to clear out mud and rock slides on the railroad tracks during winter storms.

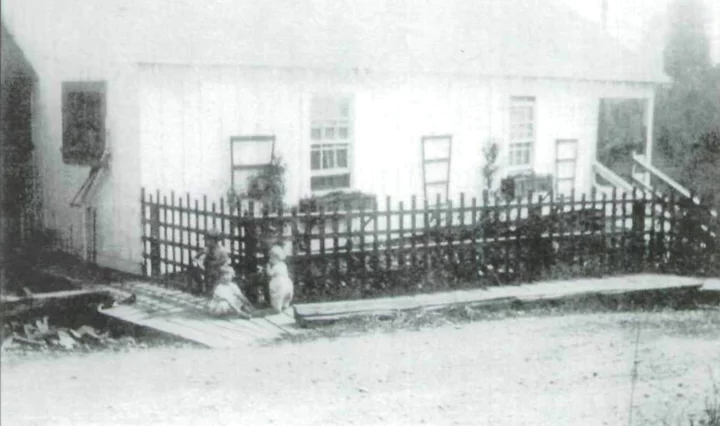

The author, Wes Walch, with his sisters, Mae Pauline, Belva, and June Ann, in 1933. Photo courtesy Wes Walch, via the Humboldt Historian.

Even after the Depression, money was still scarce for my family and most others in Crannell. I do recall as a child my parents and our neighbors playing cards and drinking homemade beer that my dad and most of the men made. While the men played pinochle in the dining room, the ladies played Parcheesi in the kitchen. I remember this because my small bed was next to the wall in the dining room, and I would fall asleep with my dog Poochi lying beside me, listening to the men talking and laughing at the table.

Such get-togethers and the Saturday night dances were the entertainment in those days. And we did have a big cabinet Philco radio. Whenever President Roosevelt would give his weekly radio talks to the nation, all the grownups tuned in, listening to his every word. All of us kids would have to be quiet and not make a sound when President Roosevelt was on the radio.

Even when our folks had very little money, we always had plenty to eat. My dad raised chickens, geese and rabbits, and we had a big garden. When old enough I helped my dad spade and plant the garden and my sisters kept busy picking the vegetables and helping our mom with the canning. Deer, ducks and fish were always plentiful, and it was pretty much open season all year round if you needed meat. Most of our fresh fruit and corn came from Pepperwood and Shively. My grandmother would bring boxes of corn, peaches, pears, apples and other fruit for canning. We had a large room next to our woodshed with shelves of canned food. The milkman and butcher wagons delivered milk, eggs and meat around town. Milk came in thick glass bottles and you could see the cream on top. If we were out by the meat wagon and hung around long enough, we could almost always get a beef wienie from the butcher as he made his rounds.

My mother was an excellent cook. Her parents, Josie and Nick Dubrovic, emigrated from Vienna, Austria and settled in Arcata. Grandfather Nick was a ship’s carpenter and he built a large two-story house at 15th & G Streets in Arcata for their large family of four girls and three boys, with extra rooms for boarders. On weekends, bachelor workers When old enough I helped my dad from logging camps and sawmills would come into town by train and board at their home. My mom grew up helping to cook for these boarders, and she also worked in her late teens as a waitress and cook in a cookhouse. She enjoyed cooking and in addition to Austrian dishes, she made delicious soups, including her specialty, Italian minestrone. Mom made her soups in large cookhouse-sized kettles, and all were welcome. On occasion, there would be over twenty kids at our house eating her soup.

The town of Crannell was a close-knit community. It was a standing joke around town that the ladies auxiliary did all the firefighting. The men would be out working in the woods during the day and the ladies auxiliary would put out the fires. The PTA met once a month at the schoolhouse, bringing potluck meals. My mom usually brought delicious kettles of tamale pie. The volunteer firemen put on town dances, for which they provided the midnight meals. Built on steep-sided hills that ascended from the valley and Little River, Crannell comprised 125 homes, with about 450 residents. Water came from several springs above town, with small reservoirs that fed into three or four fifteen foot by twenty-foot tanks. Three-inch metal pipes carried the water into town. The roads were all gravel; only the road from Highway 101 up to the company store was paved. Sidewalks, picket fences, and bridges were all made from redwood boards or timbers.

The author’s father, Weston Walch, standing on the boom of the steam crane, 1930s. Photo courtesy Wes Walch, via the Humboldt Historian.

All workers’ houses were pretty much alike. Rent was $12.00 a month for each family and an extra $2.00 for a garage. For the bachelor workers living in the bunkhouse cabins and lodge, rent was free. Houses were made with 2x4-inch studs, and 1x10-inch redwood board-and-batten siding, supported by redwood beams. Our house, like many, was built on a hillside, with the lower end some ten feet off the ground. The space under the house was used for storage and, of course, for keeping the beer vats. The inside walls were 1x10-inch redwood siding covered with cheesecloth and wallpaper. The floors were covered with bright linoleum. All houses had wood cookstoves with hot water coils and pipes that ran to the hot water tanks, standing in the kitchen corner. The tanks were not big enough: hot water to wash and bathe was a scramble for us all. Each house came with two bedrooms, one bathroom, kitchen, pantry with a cooler {no refrigerators), washroom, living and dining room, and an attached woodshed off the back porch. My parents slept in one bedroom, and until we added a third bedroom, my three sisters slept in the other bedroom, and I slept on my cot in the dining room. Our mother would get up at 5:00 a.m. to light the stove and heat the water, make lunches for my dad and us four kids, cook an early breakfast for my dad before he went to work, and then for my sisters and me before we left for school.

I still remember an almost tragic morning when I was about five years old. I was up early for breakfast with my mom and dad, and there was a flock of quail in our garden. There were no houses above us so my dad would occasionally shoot quail that strayed into our garden. He was loading a 12-gauge shotgun in the kitchen, with the barrel pointed down to the floor, while keeping an eye on the quail. Suddenly the gun went off, shooting a two-inch hole through the floor. I was standing beside him and the shot missed my foot by just six inches. His face went white. He put the shotgun away and never attempted to shoot quail around the house again.

From our house up on Hillside Terrace we probably had one of the best views in town — to the ocean on the west, up Little River to the east, the forest to the north, and the valley and bottomlands to the south. Being in the last house up the hill also meant we had the longest walk, or run, to school, as well as to the store and down to the river. This turned out to be a good thing in a way, because my sisters and I learned to run very fast. We always won money in the foot races at company picnics and at the Mattole River BBQ’s on the Fourth of July. Our dad was fast, too, and would win the men’s races. He also played baseball for the Crannell team when they were in the mid-county league. He was a left-handed batter. In one game, at Scotia Lumber Company, he hit four home runs over the short right-field fence and into the Eel River

The general manager’s house was located on the hill next to the school with a view to the Pacific Ocean. The managers’ houses were much larger, with fireplaces, three bedrooms, two bathrooms, and hardwood flooring, picture windows and fancy kitchens. These houses also had steam heat from the steam boilers, left from the days when the sawmill was in Crannell. Growing up, it was quite apparent to me that the managers and bosses had the best houses and all the perks. 1 knew then that, someday, I wanted to be one of those bosses.

The company store stood in the hollow between Hillside Terrace and Eucalyptus Heights.

Crannell store in the 1930s. Photo: Walter Warren collection at CPH, via the Humboldt Historian.

It was a large two-story building containing a department store, groceries, a meat market, and the towns post office, with individual boxes for residents. All produce and merchandise came in by railroad to a siding at ground level, and was carried to the upper floors on a large platform elevator. Mr. Gregory was the store manager. One hand-lever gas pump stood outside the store, as well a phone booth containing the only public phone in town. If we wanted to call someone we walked or ran to the store and waited our turn, as the phone was generally in use. Since it was on a party line, the calls were none too private anyway.

At one end of the store were the offices for the woods managers, safety, and payroll. It was at a sliding window between the offices and the store that one could obtain scrip money. You know the tune, “You Owe Your Soul To The Company Store,” by Tennessee Ernie Ford? Hammond Lumber Company had its own scrip money — from a copper dollar down to a penny — and each coin had an H stamped through it. If a worker was short of money before payday, he could go to the store payroll office and borrow scrip money. Of course, you could only spend the money at the company store and the company would deduct what was borrowed from your next paycheck. There was a lot of Hammond Lumber Company scrip money borrowed in those days. and many who owed their souls to the company store.

Next to the store were a barbershop, the bachelor men’s cabins, a one-room library, and the large busy cookhouse. The company cookhouse fed the bachelors and management personnel. Each day head cook Tony Gabriel and his wife and staff prepared a large breakfast of pancakes, eggs and meat for more than 75 men, a box lunch for the woods crew, and a big dinner that always had two or three choices of meat, potatoes and gravy, vegetables, and choice of pie or cake. Cookhouses were famous for their well-prepared and large meals to satisfy a hungry logger and had their reputations at stake to attract good steady workers.

Workers paid about thirty dollars a month for all their meals. Tony Gabriel was a great cook as well as an excellent baker, having studied and worked as a chef in hotels in Chicago, before coming out West. Tony would often have large cookies or a piece of fried chicken for us kids when we came by after school.

The Walch house in Crannell. June Ann, Mae Pauline, and Wes Walch, 1929. Photo courtesy Wes Walch, via the Humboldt Historian.

The company raised its own pigs in large pigpens east of town. Pork chops, roasts, ham and bacon for the cookhouse all came from these company pigs. The company garbage truck picked up scraps of food from the cookhouse and delivered it to the pigs on a daily basis. Seagulls gathered around the feeding troughs by the hundreds. From our house we could see these seagulls flying around and knew it was feeding time. The garbage truck also picked up everybody’s garbage on a weekly basis, a service included in the rent. The garbage dump was a good place for us boys to sharpen our shooting skills: we would plink at scurrying rats and shoot tin cans with our .22 rifles.

Across the river, down on the flat below the store, stood the Firemen’s Hall. The little non-denominational church stood beside it. Our sister, June Ann, was the first bride to be married in this little church and possibly the only one. The Firemen’s Hall, complete with kitchen, hosted meetings for the volunteer firemen and the Boy Scouts, as well as school plays, movies, and dances. Most folks didn’t have cars in those early days and the Saturday night dances were the big event. Everybody went, grown-ups and kids, and danced to Crannell’s own band, “Coles Californians,” led by Ken Cole. When us kids got sleepy we just lay down on one of the benches and went to sleep. Sometimes there was a little more than just dancing~a few too many beers and the fighting would start. I remember Dad coming home more than once with a bloody shirt. As recounted by my sister Belva, this would be the night that mom would make a rather lumpy bed in our large wood box just inside the back door for Dad’s discomfort.

Another big event was the Fourth of July, when Hammond put on a big picnic as a get-together for its two towns, the logging town of Crannell and the mill town of Samoa. The company transported the Crannell families out to Samoa for the picnic, twenty miles distant, on the logging crew train, and back home again that night.

BBQ beef and beans were served, with kegs of beer for the men, and soda pop for the ladies and kids. There were softball games, races for the men and kids, a tug-of-war between the loggers and the mill workers, and in the evening a dance at the Samoa Firemen’s Hall. This picnic was supposed to be a friendly get-together, but the competition coupled with the beer generally resulted in some pretty good all-out brawls between the loggers and the “sliver pickers,” which was what the loggers called the millworkers. My pal Ken Gipson’s dad, Cal Gipson, was one tough fighter and could hold his own at the dances and picnics with the best of them. My dad always claimed that he was just trying to separate or stop a fight and of course got right in the middle of it. I don’t know if it was because of the fighting, or lack of interest after people started getting cars and traveling more on holidays, but the company stopped having these “friendly picnics.”

###

The story above — an excerpt from Weston Walch’s book Growing Up in Crannell — was originally printed in the Summer 2009 issue of The Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society, and is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.