OBITUARY: Janene Diane Morris, 1963-2025

LoCO Staff / Sunday, Feb. 1 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

It is with the deepest sorrow that we have to say goodbye to our beloved mother, grandma, wife, sister, aunt, and friend. Janene Diane Morris left this world on November 24, 2025. She was loved beyond words and will never be forgotten. She lives on in her children and grandchildren, who have all inherited her loving nature and resilient spirit.

Janene was born on August 31, 1963 in Santa Cruz, California to Pamela Joan Holden Walsh and James Walter Morris. As a teenager, her first job was at the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk, which she enjoyed because she got to ride the rides for free and spend time on the beach while working. After that, at the age of 19, she moved on to her second job at Seagate in San Jose, California where she met the father of her four children, James. They connected over a shared love of music, nature, and free-spiritedness. For our mother, it was love at first sight. Our mom would later move to Humboldt County where she attended College of the Redwoods and attained an associate degree in nursing, as well as an LVN license. She went on to work as a nurse for a number of years, as well as working for IHSS later on in life. Through these jobs, she helped those in need, as well as assisted the elderly and disabled in their homes. Her career was guided by her compassionate heart and tireless drive to help others, and she made a difference in countless lives.

To her children, she was known as “Mom,” “Mommy,” “Mama,” “Mamoo,” and sometimes “Mother.” Our Mom’s greatest joy in life was being our Mom. She used to make up little songs for each of us, and never missed an opportunity to take a quick picture that we’d inevitably complain about. She’d always tell us we would appreciate them when we were older - and she was right. The picture taking saga continued into adulthood, and turned into a tradition her grandchildren would endure as well. Like Janene’s own kids, her grandkids would complain about taking “a” picture– or a million. We remember how she would tell her grandkids “picture time”, and they would respond with the same exaggerated tone - “grandma, not another one”– the same moan and groan her own kids gave her. But our mom, as the kindhearted person she is, would just carry on, not be irritated and say “you’ll appreciate it later”– and mom– we’re so glad you did, because now your kids and grandkids can look at those pictures, videos, and memories and remember the wonderful mom and grandma that we had.

Mom was always there for us– long after we were adults… to talk to, to cry to, to lean on. She showed up - rain or shine, good day or bad, she’d be there with a fresh tray of brownies, a warm hug, a cathartic singalong session in the car, or most often– just someone to talk to who understood and would listen without judgement. She would have done or given us anything and everything if she knew we needed her. We knew that with each laugh or cry, every goodnight kiss, every burrito wrap to tuck us in, every mud pie you pretended to eat, every slide and swing you gave us a gentle push on, every boo-boo you would fix with your magic mom touch– we had a mom who wanted to be a mom. Her children knew with every bad dream, every bedtime story or morning wakeup, every dance and song we shared– that we had a mother that loved us deeply. Despite every time our mom was giving us her love and one of us kids would say “MOOMMM!… come on” in an exaggerated tone of voice– we knew that we were lucky to have a mom who loved us so completely. Our mommy also never missed a chance to watch one of her kids in a performance, whether it be a recital, play, or even a school project us kids waited until the last minute to do– even though she had been repeatedly reminding us to do it. She would be there - no questions asked. We got to experience it all. Another thing our mom would do to nourish us in the make believe realm is allowing us to perform numerous plays for her at the house; she never complained, she just enjoyed watching us be happy. When we were kids, we begged for the game Tales of the Crystals– if you know, you know. The game required us to take over the entire apartment so that our imaginary land could replace reality– and our mom happily allowed us to do that… even when the “land” had to stay that way for multiple days. Even when we wanted to build forts that made parts of our house unreachable. Our mom just wanted us to be happy and feel loved. To be free and to be children. That we could always count on. Thank you for letting us explore the world with you and showing us what adventure and family really is.

Janene has always loved good music– she loved rock– especially 70s acoustic rock. She loved folk, country, and sometimes music that was on the heavier side just so she could dance to it– music like Rihanna or Pink. When her children were younger, as a family, we would listen to artists such as John Denver, Eagles, Garth Brooks, Tim Mcgraw, Tom Petty, Neil Young, and Eric Clapton, as those were some of her favorites. She also loved listening to her husband James play guitar. Our mom would love to sing along with her eldest daughter while James played guitar and joined in on the singing. Our mom loved music, singing, and dancing– and made sure her kids knew what good music was.

Janene loved the ocean, the mountains, and being in the trees. She always wanted to be in and with nature– that is just the environment where she felt the most herself. She loved art, photography, the beach, and enjoying coastal vibes. She would spend a lot of her time hiking, sun bathing, swimming in the ocean or river, lovingly nurturing her garden, and generally being out in nature. Due to our mom’s love of nature and water she would often refer to herself as a mermaid. When we would ask what she meant by that, she would say that she both loved the water and being a free spirit. When she briefly moved away from Humboldt, she said that the air felt too dry. When she came back, she was so happy to see the ocean and feel the sea spray again. She used to love to collect seashells, river rocks and agates, and likened herself to a myna bird because of her love of shiny things.

She also loved the forests, especially our local redwoods, and often took us all camping in our youth. She’d set up the outrageously large tent– we’d roast marshmallows, take hikes, go swimming, cook food, and just laugh and enjoy each other’s company. Our camping trips only ended in narrowly avoided disaster two times– once when we had to flee from a nearby mountain lion in the middle of the night. Still fun. On the other tiny mishap camping adventure, there was a sudden storm that involved buckets of rain entering our tent. We woke up to a flood, and retreated to our car to spend the night. Scary and uncomfortable, yes, but we all knew we were loved and safe together as a family who loved each other. Nothing made us feel more loved and protected than to know we were safe in our mother’s warm caress. Our other outdoor adventures we would have with her were dancing in the rain, building a snowman in the cold winter months, sledding and finding our family christmas tree, swimming at swimmers delight, bike riding and hiking as a family, and most of all going to the beach and looking for agates for hours, even though we barely found any. Our family was just glad we were enjoying each other’s company. We love you mom, more than one could ever know.

Janene also had a deep and profound love for animals– all animals… although her love for dogs was always the deepest. Our mom used to tell us stories of all of the stray animals she used to bring home growing up– and that continued as a tradition in our family. When she was little, she’d beg her parents to keep every little creature she found - from kittens to wild bunnies. She loved horses, and always dreamt about having a chance to ride again. Our mom used to speak of her sweet childhood dog Fifi– a dog she never forgot. When her children were young, we had a Malamute named Wima and Priss the cat. Later on we got our family dog Lily, and then when her kids grew up and became adults she adopted Yuki– who had a litter and our mom kept two of the pups– Oddie and Embry. Oddie and Embry were like her children after her children no longer lived at home. She used to say to them, “I will never hurt you, and you will never hurt me”. She was incapable of doing any creature harm, and wouldn’t even crush a spider. If she found one on the edge of her bath, she’d get out just to usher it to safety, all while gently scolding it like it was misbehaving. She considered pets to be part of the family, and treated them as such.

Her younger brother describes her as follows while they were growing up: My sister always had a strong love for animals. Our Dad lived in Texas for most of my life. I remember a time when he was coming to visit us in Santa Cruz and Janene (like many young girls), wanted a pony. So when my Dad came to visit us he actually bought her a Shetland pony. Lucky for us, we lived in a house with a backyard at the time. She was so happy that she had a real pony. She had to be around 13 or 14. She would always bring stray dogs and cats home as she got older. And my mom could never tell her no, so we had a lot of pets growing up. My favorite pet I’ve ever had was one she gave me when I was 12 or 13 years old - a Springer Spaniel dog named Bogart. I loved that dog so much. Janene had such a big heart and cared about people and animals. We used to fly together to Texas every Summer to visit our Dad. I miss those days– we had so much fun together riding horses, camping, fishing, and visiting family. There were a few times in my life when I needed a place to stay until I got back on my feet– and she always had a spot for me to stay. I can’t believe she’s gone. Time flies by so fast. But I’ll never forget her or the good memories in my heart and mind. Love you and miss you sister.

Her eldest daughter would like to say the following:

My mom is my best friend. No one can ever replace her and I am so grateful that I got to know what it feels like to be truly understood and loved for all of me. My mama is the most loving person I have ever known and she has taught me how to love. My mom is the reason I am kind, loving, forgiving, and deeply loyal to my family. My life has not been an easy one and I honestly cannot imagine how I would have made it through without my mom. She never gave up on me and always made me feel like I was perfectly loved and always forgiven– without question. I have never felt love without regard or judgement like my mama gave me. Everything about my mom reflected love and kindness– she used to tell me that “everyone’s fancy, everyone’s fine” – something she learned from my grandma that was meant to mean– be kind and loving to everyone, even when they are different from yourself. I truly believe that I am who I am because of my mom. I am so much like her and I am grateful for that beyond words. I do not know if I will ever heal from losing you mom– but you have taught me so much and I know you are always with me. I can feel you and your love in me when I think of you and when I am near my siblings. We will try to do what we know you would want us to do– to love each other and not give up. I hope you are at peace mommy– swimming with the mermaids. Trunkateers for always- your Bumbo sure will miss you. You know how much I love you- forever and a day.

Her second eldest daughter would like to say the following:

As the second oldest daughter, I got to experience the undying love our mother had for each of her children. Our mom was our security blanket, our friend, our mother, our mentor and teacher, our companion in life and we were hers. Our mom taught us how dangerous people in this world can be, but she also taught us to respect them, and to know they’re acting a certain way based on hardships or disasters in their own life. Thanks to our mother I have a love of life, a love of animals and nature, a love for photography and a loving spirit, yet a spirit to never give up no matter what life throws at you. We are resilient because of her. She had the most nurturing, kind hearted soul I ever met. She taught all of her kids to be strong and confident human beings. But most of all, she taught me that being unique is not a bad thing but a trait everyone wishes they have. My momma’s other greatest joy in life and proudest moment was getting to be a grandmother to her five grandchildren. She would not interact with her grandchildren as a whole but interact with them as the individual person they are, supporting them through whatever they needed at that time, whether it would be playing, talking with them, or just being there to offer a hug and kiss, she would be there just like she was there for us. No one could ever take that love and joy away from her. Our mama was sadly taken from us too soon. But mom, we want you to know you’ll always be a part of us. Your legacy lives on in your children and grandchildren. Thank you for always tucking us in at night, checking our room for monsters, letting us entertain you with our recitals, styling our hair when we were having a bad hair day, always believing in us, and waking us up in the morning with your warm wake up and smiling embrace.

From her son:

Grief is not a series of boxes to check off. It is not something that can be outrun. It is a sign that someone existed, and continues to exist. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to write anything because I’m still so sad, and so angry, and there are no words to express any of it. My mom was a beautiful, kind, flawed person, who left us far too soon. I will remember her for her smile, for her gentle singsong voice, for the way she carried herself, and the way she made me feel loved. She cherished peace, and she never once made me feel like I didn’t belong. So I grieve her. And I will carry my grief, just as she carried me, and nurture it. I will always love you, Mom, and I hope to join you again one day. Until then, you will be in the beautiful gardens, as my journey continues in your memory.

Her youngest daughter would like to say the following:

As the youngest daughter, I was always her baby, and she was always my mommy - even when I was very much an adult. When I was little, she used to call her arm a wing when she was snuggling me, and me her baby owlet. She always made me feel safe. I always knew she loved me - that was a constant in my life that I never had to question. She gave me her love of video games - she had a particular fondness for horror games like fatal frame and silent hill. She also gave me her love of reading; she especially loved mysteries and Steven King novels. And, of course, she gave me her love of animals. I vividly recall the time we thought it was a good idea to try to ride a couple of random horses that we found bareback. She insisted that she go first - as was her responsibility as the mom, naturally. It ended as one would expect. But I’ll never forget that side of her - the wildness, the zest for adventure, the unwavering trust in animals and the humor to laugh about being thrown from one that weighed about 1,000 pounds. She taught me to see the good in everyone, to never wish anything harm, and to never give up. And even though the world wasn’t always kind to her, she was always kind to the world. I’m who I am today because of her, and I’m infinitely better for it. I just want to tell her thank you - for chasing away every bad dream, never complaining when I “borrowed” your makeup, teaching me what kind of mom I wanted to be, and showing me how to look for the light in the darkest of places. I love you, mommy. Sweet dreams.

Janene is preceded in death by her mother and father, her brothers David, Mark, and Larry, and her sister Star. She is preceded in death by her dogs Fifi, Wima, Lily and Yuki, and her cats Momo, Haru, and Tibbleton. She is survived by her four children– Darrah, Breanna, Jesse, and Juliet. She is survived by her husband, James. She is also survived by her grandchildren– Clover, Luna, Thea, Korra, and Leo. She is survived by her brothers Jimi and Michael and her sister Pamela. She is survived by her many nieces and nephews– Shay, Sara, Danny, Justin, Adam, Malia, John, Allen, Ariel, Gabriel, Elijah, and Jake– as well as their children. She is survived by her two dogs Oddie and Embry and her cat, Katie. Those that remain wish they never had to say goodbye.

To that we say we love you mommie, to the moon and back, forever and a day, always and back again. Although you are no longer with us, you are not gone. You’re in the ways that we love each other. You’re in the smiles of your grandchildren. You’re in the smell of falling rain, and the sound of cresting waves. You’re in every deep sigh and even deeper laugh. You’re in lessons you’ve taught us and how much we know how to love. You’re why we know that we will always be accepted for whoever we are. You’re in the little acts of kindness, every bug we can’t bring ourselves to squish, the late night snacks and early morning coffees, and the way we hold each other just that little bit tighter now. You’re in the way that we know we will be ok someday. You’re not gone– you’re everywhere. And we love you, always. Thank you for teaching us how.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Janene Morris’ family. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

BOOKED

Today: 8 felonies, 8 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

Blue Lake Blvd / Acacia Dr (HM office): Trfc Collision-1141 Enrt

ELSEWHERE

Governor’s Office: Governor Newsom announces funding for LA fire survivors to access pre-built housing to further speed recovery and maintain neighborhood character

RHBB: Caltrans, EPIC Clash Over Tree Cutting in Richardson Grove…Again

KINS’s Talk Shop: Talkshop February 2nd, 2026 – Brian Stephens

KINS’s Talk Shop: Talkshop February 3rd, 2026 – Bill McAuley

51-Year-Old Man Arrested for Attempted Murder in Redwood Park; 75-Year-Old Victim Airlifted Out of Town

LoCO Staff / Saturday, Jan. 31 @ 6:10 p.m. / Crime

Press release from the Arcata Police Department

On the morning of January 30, 2026, officers with the Arcata Police Department were dispatched to the area of Trail 5 in the Arcata Community Forest, between Diamond Drive and California Avenue, for a report of an adult male with facial injuries.

Responding officers located a 75-year-old, male, an Arcata resident, with severe head injuries on Trail 5. Emergency medical personnel responded, and the victim was transported to St. Joseph Hospital before being flown out of the area for treatment of life-threatening injuries.

Due to the severity of the injuries and the circumstances surrounding the incident, the Arcata Police Department’s Investigations Unit assumed responsibility for the case.

Through the course of the investigation, detectives determined the incident was an intentional assault and identified 51-year-old Shawn Kolpak as a suspect.

In the early morning of January 31, 2026, Arcata Police officers located Kolpak in his vehicle on the 700 block of 13th St. in Arcata. He was taken into custody without incident and booked into the Humboldt County Correctional Facility on charges of attempted murder (Penal Code 664/187(a)).

This incident is believed to be isolated, and there is no ongoing threat to the public. Redwood Park remains open to the public.

The Arcata Police Department would like to thank community members who assisted in the investigation and helped ensure the safety of the community.

Anyone with information related to this incident is encouraged to contact Arcata Police Department Detective Sergeant Victoria Johnson at 707-822-2424.

(PHOTOS/VIDEO) Nurses Hold Vigil for Alex Pretti at St. Joe’s; EHS Students Walk Out of Class to Demonstrate With the Community

Hank Sims / Saturday, Jan. 31 @ 10:46 a.m. / Activism

Local medical professionals, along with other members of the community, held a candlelight vigil for Alex Pretti, the man killed by ICE agents in Minneapolis last week. Austin Allison, a nurse surgical technologist and a former member of the Eureka City Council, took the video above.

A bit earlier in the evening, students walked out of Eureka High to join a demonstration at the Humboldt County Courthouse. EHS student Candance Biane took a ton of pictures, and was kind enough to share them with us. You can find a selection of them below.

As a reminder: There’s another, 50501-led demonstration at the courthouse scheduled for noon today.

(PHOTOS) Late-Night Fire Puts Beleaguered Eureka Apartment Building Out of Its Misery

LoCO Staff / Saturday, Jan. 31 @ 10:45 a.m. / Fire

Photos by Jasmine Wheaton.

###

A structure fire consumed the long-vacant apartment building at 833 H Street in Eureka last night. Emergency personnel were called to the scene after 1 a.m.

This place had a troubled history. Long owned and managed by local slumlords Floyd and Betty Squires, the building was condemned by the city in 2018. The most recent Google Street View image shows its dilapidated state in October 2024.

However, Facebookers note that contractors had been working on the structure recently, with more improvements scheduled to begin soon.

The Outpost will update readers if and when more details are available.

THE ECONEWS REPORT: Fix Fourth and Fifth Streets!

The EcoNews Report / Saturday, Jan. 31 @ 10 a.m. / Environment

There is a traffic safety crisis on 4th and 5th Streets in Eureka. These streets are extremely dangerous for people walking, biking and rolling. While Caltrans has made some improvements to crosswalks, there are currently no plans for major safety improvements to 4th and 5th Streets.

Colin Fiske of the Coalition for Responsible Transportation Priorities (CRTP) joins the program to discuss how street design increases car crashes and pedestrian strikes and how Caltrans could immediately improve safety in Eureka.

Want to take action? CRTP is petitioning Caltrans to better prioritize road safety improvements on 4th and 5th Streets.

HUMBOLDT HISTORY: An Itinerant Bookseller Peddles His Wares Around 1870s Humboldt

Harriet Tracy DeLong / Saturday, Jan. 31 @ 7:30 a.m. / History

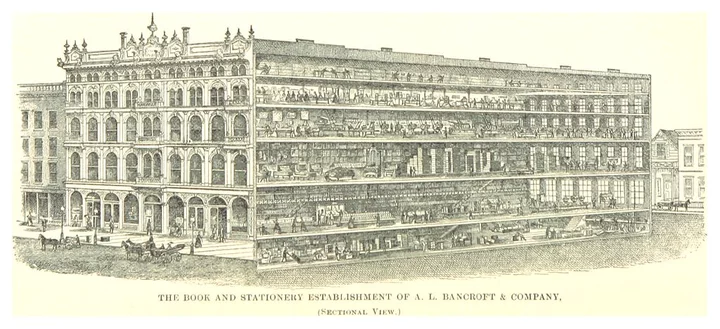

The A.L. Bancroft print factory on San Francisco’s Market Street. Image: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

###

John Morris never lived in Humboldt County. Two of his sisters, Harriet Tracy and Lucy Bartholomew, did. His first wife, Melissa Harmon, was a Eureka girl. John Morris was a traveling book agent for A. L. Bancroft. Humboldt County was part of his territory in 1871 and again in 1874.

Book selling was a lucrative job for a man willing to work hard and travel through unknown territory. Profits were high and expenses negligible, since he traveled on foot and frequently availed himself of the hospitality of settlers for his food and lodgings.

In the spring of 1871 he received word that Humboldt County was a fertile field for book sellers. His sisters, Lucy and Harriet, had joined Lucy’s husband, Mitchell Bartholomew, in Hydesville. This seemed like a good time to undertake a trip through the northern part of the state.

Times were not too good in the lumber industry that summer; his sales were limited to 20 books in Eureka. The cattle and dairy industries, however, were both on the rise, which meant good business for him in the Mattole region and the Eel River Valley.

As he traveled about Humboldt County he noted that the farmers had invested heavily and well in potatoes that year, putting as high as 400 acres in that crop. He was impressed by the diversity of the people of the county — the lumbermen from Maine and Canada, the Danes in the dairylands, the stockmen from the midwest and south, and the southern Europeans along the seacoast. He was impressed by the fact that all over the county he met rich and influential men — Judge Huestis, William Carson, George Williams, Jos. Russ and Captain Wasgatt.

He was warned that in the Mattole region most of the men had married Indian women and that neither the men nor their women could read. He tried anyway and came triumphantly back to Eureka with an order from every family in the Mattole. One man, he said was a graduate of Harvard and bought two books. Another, who could not read, bought a book when his hired man promised to read it to him.

Rohnerville was the most lucrative city in the county. There he sold 42 books in one day, the largest day’s sales he had ever achieved.

For the return trip to San Francisco he bought a horse and a revolver, loaded the horse with books, and started out from Hydesville overland.

He arrived at Garber’s on election day and found that little settlement crowded with ranchers in from the surrounding mountains to cast their votes. He listened to election speeches and sold most of his books to the men gathered there.

The next day he rode with the stockmen back to their mountain homes east of the Eel River. He described the Coyle place: “A small shanty, sides, roof and all of the roughest shakes I had ever seen. A nicely dressed, good looking young lady came out of the shake shanty. Mr. Coyle introduced me to his wife, asked me to get down and eat dinner with them. In 30 minutes we sat down to a sumptuous dinner cooked by this young wife: meats, fruits, preserves, everything good.”

That night it was on to the Beaumont Ranch, where he “found intelligent people. The Beaumont brothers were highly educated Frenchmen who could read the dead languages, and who had a fine library.” The next day he stopped at Armstrongs, where he sold three books.

All in all John Morris was very satisfied with his first visit to Humboldt County. He was impressed by the intelligence and resourcefulness of the settlers. He remarked, “Though like Coyle’s, the outside might look woeful rough, inside the house might be carpeted and have all the latest improved furniture, if only a man had money and pack-mules to get these improvements out to the ranches.”

###

In October of 1874, John Morris returned to Humboldt for another book canvass. This time he particularly had Eureka in mind, the city where he felt he had failed to gain the confidence of his customers in 1871.

On this trip to Humboldt he sailed on the steamer Humboldt, which he felt offered better accommodations then the old Pelican.

Landing in Eureka, he immediately sought out his old friends of Nebraska days, James Gardner and his wife and their two daughters. Prudence (Mrs. John) Dodge and Elizabeth (Mrs. Franklin) Ellis. These families had known each other not only during the days in the midwest, but also in the Trinity mines, where the Morris family owned the hotel at Minerville. Mr. Morris says that John Dodge at one time owned the “big ditch built by Lt. Governor Chellis in Trinity Co.” It was John Dodge who owned an extensive tract of land in Eureka in the area of J Street, where he employed both his brother-in-law. Franklin Ellis and his father-in-law, James Gardner.

Will Dodge, whom many old timers will remember in the old home on J Street, was a baby at this time. The story goes that old Mrs. Gardner often cared for Will, and to amuse him would hold him up to the window to watch his grandfather working in the garden. “Look, Willie,” she would say, “Watch Grandpa dig, dig.” And so the boy grew up calling his Grandfather, “Grandpa Dig-Dig.”

John Morris took a room at the Dodge’s for $5.00 a week, with board thrown in. “Prudence was a good cook,” he said. This time he found Eureka a booming community — lumber mills were running at capacity. Shipbuilding and shipping were in full swing, and a number of shingle mills were running. There were sidewalks made of thick redwood boards, which were a boon to walkers and made it easy to travel about town. He found churches thriving, naming the Congregational, Methodist, Episcopal and United Brethren.

The day he spent selling at Carson’s Mill was one of the highlights of his stay in Eureka. He tells the story this way:

Carson’s Mill at Eureka was the most desirable mill to sell books, but I could never sell a book to William Carson.

One day, on going to Carson’s Mill, I found the crew idle. The mill had stopped. When the owner came round I made a friendly remark, “You have a fine mill, Mr. Carson.”

“Sometimes I think so, sometimes I think not.” This was one of the days he thought not, no doubt, for after all hands who wished had signed for a book and I was sitting on a big log outside the mill, I heard a voice over my shoulder that nearly bounced me from my seat.

“I have one request of you,” he said, “That you don’t talk books to my men during mill hours.”

John Morris assured Mr. Carson that he would never bother the men while they were working, and Mr. Carson wandered off, satisfied.

It was during this three months’ canvass of Eureka that John Morris met and married the lovely Melissa Harmon. John described his first meeting with Melissa: “As I watched Melissa sewing that evening, stitch by stitch she wove the web of her beauty vividly into my mind’s eye. To see her was but to admire, to know her but to adore.”

They were married three months later, on January 27, 1875. There were 25 people crowded into the Harmon house for the occasion, but the man who stood out in John’s memory was the minister, Mr. Ed. I. Jones. Of him he said, “I did not like the preacher who officiated. He was so smart, having studied law, and had the swell-head terribly.”

John and Melissa lived for two months at he brother, Charles, home while John finished his work in Eureka and Humboldt County.

The farmers were not doing as well this year, so business feil off some. But out at Ferndale he felt pretty successful with the Russ family. The ladies of the Russ family, he said, had become interested in church affairs, and they eagerly looked through his list of religious books, purchasing one called “Our Father’s House.” Two more books of importance he sold to J. J. DeHaven.

Rohnerville, Hydesville and the Island were all quiet this year and not too remunerative. At Table Bluff he met Mr. Howard, who, he claimed, owned the bedstead upon which General Grant slept at Fort Humboldt, and also Seth Kinman, maker of chairs for presidents.

Despite the fact that business was slow in the farming communities, John Morris cleared $800 that winter, “beside the value of my wife,” he added.

A sad postscript to John Morris’s marriage awaited him when he returned to Eureka to take his bride to his parent’s home in Napa County. While he was gone she had consulted Dr. Schenk and Dr. Hostetter. Both confirmed that she was a victim of consumption and had only a few years to live.

Sadly, he took her south, where she bore him a son, Vincent, and five years later she died.

Mr. Morris continued selling books up and down California for several years before buying a ranch on Howell Mountain near St. Helena and turning to full time truck farming. He visited Humboldt occasionally in the years to follow and later Vincent was a frequent visitor at the home of his aunt and uncle, Joseph and Harriet Tracy.

###

The piece above was printed in the November-December 1971 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

OBITUARY: Jefferson Mark Wiedemann, 1951-2026

LoCO Staff / Saturday, Jan. 31 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Jefferson Mark Wiedemann

Sept. 7, 1951 – Jan. 17, 2026

It is with sadness that we announce the passing of Mark Wiedemann. Mark recently lost his battle with complications from non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Mark was born in Lexington, Kentucky, to Jeff and Dorcas Wiedemann. As the firstborn, he was later joined by siblings Randal (Martha), Holly (Bart), Britton (Erin) and Hope (John). He attended The Lexington School, Sayre School, St. George’s Prep School and Transylvania University, where he earned his undergraduate degree. He also attended the University of Kentucky and received a bachelor’s degree in nursing. He then moved to San Francisco, worked as a registered nurse, and obtained a master’s degree in environmental science from the University of San Francisco.

After serving as a critical care nurse, he returned to Lexington to earn a Doctor of Medicine degree from the University of Kentucky in 1991. He returned to California, where he met his wife, Jackie, and they married in 1991. They moved to Saginaw, Michigan, where Mark completed his residency. After a stint in Coos Bay, they headed south to Arcata.

They settled in Arcata, among the redwoods and surrounded themselves with nature and animals. Over the years, they cared for dogs, cats, chickens, goats and horses. He had a pet horse, Mr. Ed, and taught him to “count.” Mark’s passion for creation was fulfilled as he built a series of structures, including a woodshop, barn, hobby studio and greenhouses to grow grapefruit and winter tomatoes. He was a remarkable Renaissance man.

He recently built a massive redwood slab table measuring 9 feet long and 4 inches thick from wood milled on his property. Somehow, he moved it onto a deck 20 feet above the ground entirely by himself.

He was always fixing things and had a multitude of projects underway. He enjoyed growing vegetables, fruits and flowers, which were mostly enjoyed by wildlife such as deer and bears. He was also a beekeeper. Mark enjoyed woodworking, painting and tinkering for decades on his beloved “Blue Goose,” a 1950s GMC police/ambulance Carryall, restoring it to better-than-mint condition.

He dug steps into the hillside of his property and moved mountains of dirt while contouring his yard with a tractor. He created a water system that ran to his house, small orchard and greenhouse, all fully automated.

Mark’s conscientious care for his fellow human beings led him to practice family medicine and emergency medicine. Later, he focused on wound care. His compassionate nature extended not only to humans but to animals as well.

Mark’s Christian faith shaped how he lived, learned and treated people. He was a faithful member of Telios Christian Fellowship, attending Sunday services and midweek Bible study, later participating virtually. For many years, he also supported Monday Night Torah through his regular weekly presence and took part in other classes, including Einstein’s Theory of Relativity and close-up magic. He will be sorely missed by all who knew him.

He is survived by his wife, Jackie; his siblings; and nieces and nephews: Emily (Benjamin), Adam (Hannah), Paul, Seth (Taylor), Josh, Hannah (Craig), Brittjan (Rachel), Eliza, Christopher, William, Breanna, Emmie, Henry, George, Oliver, Lauren (Kevin), Alex (Lindsay) and Carmen.

A remembrance gathering will be held Feb. 14 from 2-4 p.m. at Telios Christian Fellowship, 1575 L St., Arcata. An additional remembrance gathering will be held in Kentucky at a later date. In lieu of flowers, the family requests donations be made to the American Cancer Society.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Mark Wiedemann’s family. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.