ICE Agents are Raiding California’s Largest Cannabis Grow Operation Down in Ventura and Santa Barbara Counties Today

Hank Sims / Thursday, July 10 @ 3:24 p.m. / Cannabis

Glass House Brands logo.

Glass House Farms — California’s largest cannabis cultivator, with a reported production capacity of 600,000 pounds per year — is the target of immigration raids in Southern California today.

According to reporting on the ground, the company’s facilities in Camarillo (Ventura County) and Carpinteria (Santa Barbara County) are the scenes of large-scale ICE raids. Protesters have gathered at both locations, with reports of federal agents using tear gas or pepper spray to push the crowds back.

The Santa Barbara Independent, reporting from Carpinteria, says that Rep. Salud Carbajal, along with two councilmembers, were held back by agents as they tried to gain access to the facility while the raid was underway.

Coincidentally, Glass House just cleaned up at the California State Fair’s “Golden Bear” awards for cannabis quality, winning 15 gold, silver or bronze awards in the “mixed light” category.

BOOKED

Today: 7 felonies, 10 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

5700 Mm101 N Hum 57.00 (HM office): Assist CT with Maintenance

ELSEWHERE

EcoNews: Plankton Sampling | July 18

RHBB: Powerline Fire Near Dean Creek Road North of Redway Cuts Power to Over 800 Customers this Evening

CBS News : FDA approves new blue food dye derived from gardenia fruit

CBS Bay Area: Sonoma sheriff identifies victims in separate weekend drownings

In Three Weeks, One Humboldt Native Will Attempt to Ride Horses Over 600 Miles Across Mongolia

Dezmond Remington / Thursday, July 10 @ 1:49 p.m. / LoCO Sports!

Photos courtesy of Jenn Laidlaw.

The first thing on Jenn Laidlaw’s mind while she’s helping a horse give birth is the time of day, because going to bed after 3:30 in the morning sucks. In fact, it feels worse than just staying up, so she doesn’t bother going back to bed at all. The horse emerges, preferably led by a head and two legs, and its life and Laidlaw’s day both start at around the same time. Two hours later, the foal can stand, and Laidlaw’s probably back to tending to any of the other dozens of mares she cares for.

Next month, Laidlaw is tackling the Mongol Derby, the longest horse race in the world. Racers cover over 600 miles of Mongolia in 10 days or less, swapping out stocky Mongolian horses provided by families along the way every 20 miles or so, from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. every day. It’s a grueling reenactment of Genghis Khan’s own, centuries-old version of the Pony Express, a mail system that could supposedly get a letter from the Mongol capital to modern-day Poland in less than 12 days. Now, riders pay upwards of $20,000 to complete the route, and sometimes as many as half of them quit before the race is over.

Laidlaw is, by her own admission, not much of a rider. She mainly works on the managerial side of operations at the horse farm in central Kentucky she runs. She breeds studs, some of them very successful; Code of Honor, a horse she helped raise, took second at the Kentucky Derby in 2019, and plenty sell for more than a house’s down payment.

A Fieldbrook native, Laidlaw, 39, just never kicked the common childhood fascination with horses, and that’s the furthest she can explain the obsession. She raised pigs and sheep for the Future Farmers of America and 4H (“My dad called them ‘expensive lawn ornaments,’ which they actually are”) and showed them at the county fair in Ferndale. During predawn staging sessions, she could sneak away for a minute and groom the racehorses. It made her mom mad, but Laidlaw thought it worthwhile. Watching the horses race stoked the interest, and when she graduated from McKinleyville High School in 2004, she decided she’d study equine science at the University of Kentucky. In horse racing, that’s where the money is.

She’s pretty sure she’s the first person from Humboldt to race the Mongol Derby. Growing up in one-road Fieldbrook, she didn’t know how large the world was.

“I just want people to know you can do anything you want to do,” Laidlaw said in an interview with the Outpost. “And, yeah, I’m sure that there’s crazy little horse girls still up in Humboldt, so maybe they can see this and then want to go do something similar.”

She now oversees a farm with 50-something mares. She once had a horse of her own, but sold it a few years back.

“I do not have the stomach for that much invested in something that can die,” Laidlaw said. “I’m just not into it, you know? I’d rather spend the money on going to Mongolia, I guess.”

The race is a true epic — it’s easy to imagine a Hollywood studio in the ‘50s pouring tens of millions into a film about plucky vagabonds battling the elements and navigating strange, new foreign societies while racing flat-out into the hinterlands. It would be shot in Technicolor and have a runtime of three and a half hours, overture and intermission not included.

Riders cannot weigh more than 187 pounds dressed to ride to avoid hurting the horses, and that includes the mandatory helmet, boots, and snazzy form-fitting jodhpurs. The rest of their luggage has to clock in at less than 11 pounds, and that includes everything besides water. The Mongolian horses provided stand between 12-14 hands high, and though many of them were bred to be racehorses, some of the stock are workers who do whatever task is asked of them.

“Anyone who mistakenly calls them ‘ponies’ will rescind the judgement after riding these diminutive powerhouses,” the race website reads. “These are the same hardy beasts that carried the Mongol warriors over half the world…Accustomed to heat, cold, hunger, thirst, flies, floods, deserts and really anything else that Mongolian mother nature can throw at them, they can cross terrain that would make a thoroughbred weep and maintain speeds that would put them in contention in many a tough endurance ride.”

It’ll be the first time Laidlaw has traveled to Mongolia, though she’s thought about competing in the Derby since 2012. Her roommate at the time completed it, and her blog and social media posts during the race impressed Laidlaw. Blog posts and photos from the race’s media people affected her as well; Laidlaw said their live streams, interviews, and the beautiful shots of riders adventuring in the Mongolian countryside was incredible enough to make her want to go for it.

But mainly Laidlaw needs an adventure, a getaway from a job with actual life-or-death responsibilities (“People say they have bad days at work all the time. I’m, like, ‘Did something die?’ And if the answer is no, I’m, like, ‘Did you really have a bad day at work then?’”) and a recent past marked by the death of her dog and her grandmother.

“I keep joking that my life this year is like a country song,” Laidlaw said. “My wife hasn’t left me yet because” — she laughed — “I don’t have one. I can kind of joke about it now, but it’s been hard.”

Going to Mongolia and riding horses unlike any she’s ever raised from one nomad family to the next for 10 days just kind of happens to be the way she’s decided to have the adventure. She applied to compete in 2023, and in a brilliant stroke of fate, learned she was in the same day she received a job offer.

“There was a lot of ‘Yes’ that day,” Laidlaw said. “…It was a good day. And, you know, ‘Hello! You need to choose one or the other.’ I’m like, ‘Nah, we’ll just do ‘em both. I’ve got two years to get ready. I’ll be fine. It’ll be fine. And those two years have gone by really fast. Really fast!”

Laidlaw hasn’t prepared the way she would have liked to. She’s never done an ultra-endurance ride before; most of her horse riding experience comes down to the occasional lesson and infrequent jaunt back when she owned her horse. She’s done a little bit of training on the farm with a “semi-feral” horse that flipped on top of her, dragged her across a wall, and stepped on her the last time she rode him, supplemented with spin bike classes and doses of manual labor. Still, she’s not that concerned about the probability of failure.

“From what I’ve been told, you can never really be prepared,” Laidlaw said. “Being fit mentally is probably the hardest part, from what I’ve heard, and I’m pretty sure I’ll be OK. [I’ve] been through enough. I’ve done a lot of crazy things. My job really revolves around these kind of things. There are so many kinds of situations where I’m like ‘I don’t know if I can. I’m exhausted. I don’t know if I can keep going.’ And somehow, you’re, just, like, ‘I have to keep going. I have to show up again, and we’re just going to keep doing this.’

“And I think that’s part of the reason I’m going,” she continued. “I just kind of want to test myself again — not again, but just in a different way. More of a personal challenge, because I know I can do it. I just want to prove it to myself.”

COUNCIL ROUNDUP: Eureka Approves Increased Fees for Sewer Lateral Repairs; Bayside Village Welcomes Previously Unhoused Residents to Long-Awaited Transitional Housing

Isabella Vanderheiden / Thursday, July 10 @ 1:35 p.m. / Infrastructure , Local Government

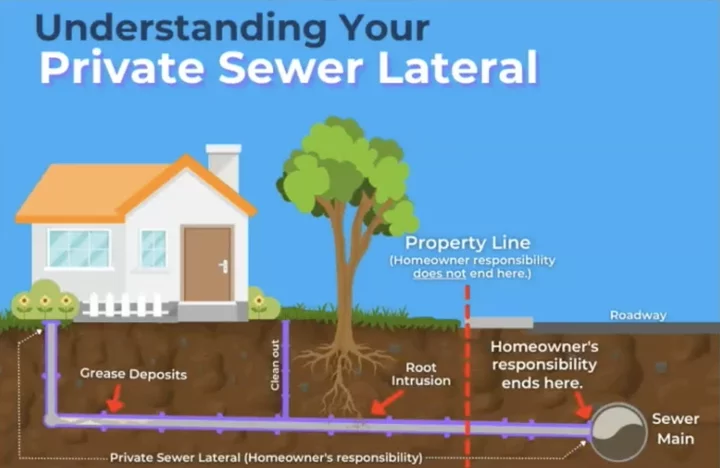

Graphic: City of Eureka

###

###

Despite widespread opposition from local realtors and homeowners, the Eureka City Council on Tuesday narrowly approved an update to the 2025-26 fee schedule that increases the cost of sewer lateral replacement for property owners with aging plumbing. The item passed in a 3-2 vote, with council members G. Mario Fernandez and Renee Contreras-DeLoach dissenting.

The updated fee schedule increases the “fee in lieu” rate for standard sewer lateral installation from $8,000 to $9,000. Costs for “non-standard installation” — complex cases where laterals are deep and difficult to access — will be determined by the city’s engineer.

A little bit of background: The “fee in lieu” system was introduced after the city council adopted the Private Sewer Lateral Ordinance in 2019, which shifted the responsibility of lower laterals — the section of sewer pipe that runs from a building’s property line to the sewer main beneath the street — to property owners. Under the ordinance, homeowners are responsible for blockages occurring anywhere in the lateral.

Not long after the ordinance was enacted, staff reported ongoing issues with property owners failing to replace laterals when necessary, largely due to the cost. To alleviate the issue, the council set up a “fee in lieu” system that gives property owners the option of paying a set fee that allows staff to undertake repairs on their behalf.

“We give folks an opportunity to basically pay into that project at … a 20 percent discount [of] what the actual bid cost was for the project, in order to have an easy way to have it taken care of,” City Engineer Jesse Willor explained at Tuesday’s meeting. “You pay a fee, and it’s taken care of for you. … It also provides an opportunity for the lower [lateral] to be done by a private contractor if the homeowner chooses.”

When the ordinance was amended, staff wrote in a point-of-sale trigger that requires a private contractor to inspect the lower lateral upon the sale or transfer of a property. If an inspection determines the lower lateral to be defective — or if it’s made of clay — it must be replaced.

Several local realtors asked the council to reconsider the fee hike during the public comment portion of the meeting. Eureka real estate agent Suzy Smith read a letter on behalf of the Humboldt Association of Realtors urging the board to lower the “fee in lieu” for standard private lateral replacement to $4,000, and cap “non-standard” installation at $8,000.

“A major issue is the current uncertainty that when you are selling or buying a property in Eureka, as soon as you initiate the sewer lateral certification application process, you may be writing a blank check to the city for your lower lateral, not including how much you will need to pay your private plumber for the upper lateral work, if required,” Smith said.

Victoria Copeland, a realtor with Key Real Estate Group, agreed. “You guys have the ability to set the fee in a reasonable, equitable way for property owners,” she said, urging the council to go “50/50” with homeowners.

Eureka homeowner Ellen P. argued that the fee increase could “make the homeless problem here much worse” and asked what happens if residents can’t afford repairs.

“What if this is too exorbitant, and my sewer does start to back up. What happens then?” she asked. “Is there going to be a lien on my property? Am I going to get foreclosed on again? If Eureka is serious about tackling our homelessness issue, this seems like a really bad idea. … [This] is just a recipe for people getting kicked out of their homes.”

Early on in the meeting, Councilmember Contreras-DeLoach indicated that she would vote against the rate increase because “people are broke.” She added that she would be “very uncomfortable with [the city] continuing to increase rates on ratepayers” whose salaries aren’t increasing at the same rate.

After making a motion to approve the fee hike, which was seconded by Councilmember Kati Moulton, Councilmember Leslie Castellano acknowledged that “no one wants to raise fees in general,” but the alternative is passing fees on to ratepayers.

“If we don’t have building owners pay for sewer lateral replacements, then it has to be paid somehow, right?” she asked staff. “It would have to be passed on to ratepayers, generally speaking, which would be more renters, more people who maybe aren’t benefiting from home ownership.”

“It would be across the entire rate-paying base, both commercial and residential,” said City Manager Miles Slattery, adding that technological advances could potentially cut costs. “There are technologies that are out there that aren’t necessarily up here, that could significantly reduce these costs. … Technology can change. Materials costs can change. A lot of things could change to make that difference.”

Councilmember Fernandez asked if staff had any idea how many laterals have been replaced to date and how many still need to be replaced. Willor said staff are almost done inspecting the city’s system, which has been done with CCTV cameras. Once that project is complete, staff will have a clearer picture of how many defunct laterals remain.

“We’re almost to the point [where] we have that data,” Willor said. “We don’t have the condition index of all of them, but we can say that we know how many we’ve replaced, and we know how many remain.”

Fernandez also expressed concern about equity. “I would rather that this public utility, at least through its usage for a public good, be a shared cost,” he said. “Is that something that is going to be solved tonight? No, but I would rather not increase it if that were the case.”

Councilmember Moulton acknowledged that owning a home “can be a money pit,” but agreed that the financial burden of lower lateral replacement should fall on homeowners.

“The fundamental piece of this for me is who owns a sewer lateral,” she said. “If that house were not there, there would be no connection to the public sanitary sewer. Therefore, that sewer, that specific piece of pipe, is serving that house, and in my mind, that makes it the responsibility of that property owner. … I think that the city offering to transfer 20 percent of the average cost to other people who are not building equity in that property is incredibly generous.”

After a bit of additional discussion, the council passed the motion in a 3-2 vote, with council members Contreras-DeLoach and Fernandez dissenting.

###

An in-progress shot of the transitional housing units being assembled. | Photo: City of Eureka

Bayside Village Welcomes Residents

After nearly eight years of planning and numerous setbacks, formerly unhoused people are moving into their new digs at Bayside Village, the long-awaited transitional community housing project at the foot of Hilfiker Lane in Eureka. Once everyone’s all moved in, the “ultra-low barrier” facility, often referred to as the Crowley Project, will house approximately 38 people and their pets.

In a presentation to the city council at this week’s meeting, Jeff Davis, project manager for the city’s CAPE and Uplift Eureka programs, said he hopes to have everyone moved into their new homes by the end of next week.

“The dining and laundry facilities, the restrooms and all but two of the residential units are up and running,” Davis said, adding that the project is grant-funded. “As of today, there are 28 individuals, 14 dogs and three cats that are residing at Bayside Village. … The goal is to continue moving folks in this week, and by the end of next week, to be fully at full capacity [with] at least 38 folks on site and additional dogs and pets, up to three per unit.”

Davis shared pictures of people’s pets and quotes from new residents — “Very grateful for a new lease on life” — many of whom have lived along the waterfront trail for 10 to 15 years. One of the new tenants has been homeless for over 35 years, Davis said.

Staff with the Betty Kwan Chinn Homeless Foundation will help manage the site, and the city’s Uplift and Crisis Alternative Response Eureka (CARE) teams will provide on-site supportive services and programming to help residents get back on their feet and move into more permanent housing.

“As soon as folks are housed through a variety of other programs, the idea is to turn this over and open this up for more folks,” Davis said. “We’re still working with folks that maybe weren’t the first 38 people to move in, but we’re still keeping up with them. We’re still providing outreach services and supportive services. … I didn’t know [this would take] several years, but it’s a reality today and I know the folks on site are extremely grateful.”

Responding to Mayor Kim Bergel’s question about children living at Bayside Village, Davis said there is a family moving in, but their kids are now legal adults. “There are several [children] that visit their parents … but there are currently none that reside there.”

Asked about the rent rate, Davis said the rent is “pretty low,” but if residents don’t have the funds, the Better Kwan Chinn Foundation will pay their rent through a scholarship or sponsorship program.

“If they are able to pay, once they leave [the program] for permanent housing, every penny that they paid they’ll be getting back,” he added. “So they’ll have that to pay for a deposit or for moving expenses, in addition to accruing the rental history.”

Each member of the council expressed their gratitude to the staff who made the project a reality, even if it took a few years longer than expected.

“This has taken a lot of endurance and perseverance … and just really appreciate you and everyone who’s been involved along the way,” Castellano said. “There are many hard things happening in the world, and I feel really proud to see the things that we’re working on. Just thank you so much.”

###

Click here for more coverage of Tuesday’s meeting.

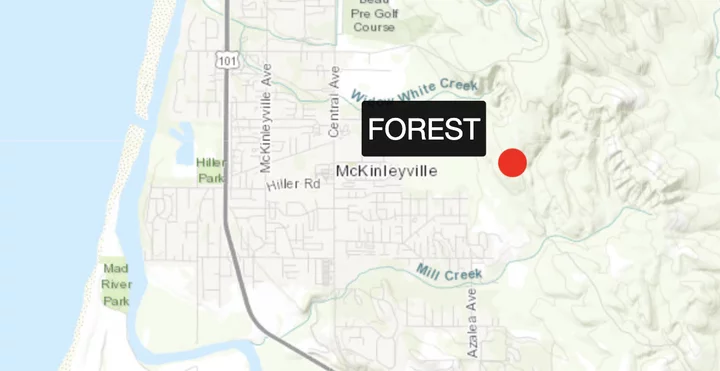

(UPDATE) Crews Responding to McKinleyville Community Forest Vegetation Fire

Andrew Goff / Thursday, July 10 @ 11:21 a.m. / Fire

Photo: Shane Mizer

UPDATE, 12:22 p.m.: McKinleyville Community Services District has announced that the McKinleyville Community Forest is closed for the rest of today while agencies respond to the blaze.

# # #

Original Post: Fire personnel from Calfire are currently battling a small blaze burning just east of McKinleyville on Green Diamond Land adjacent the McKinleyville Community Forest.

The aptly named “Forest Fire” was first detected just after 10 a.m. and smoke could be seen from town. Scanner traffic indicated that crews were attempting to find best access to the site via Murray Road.

We will update when we know more.

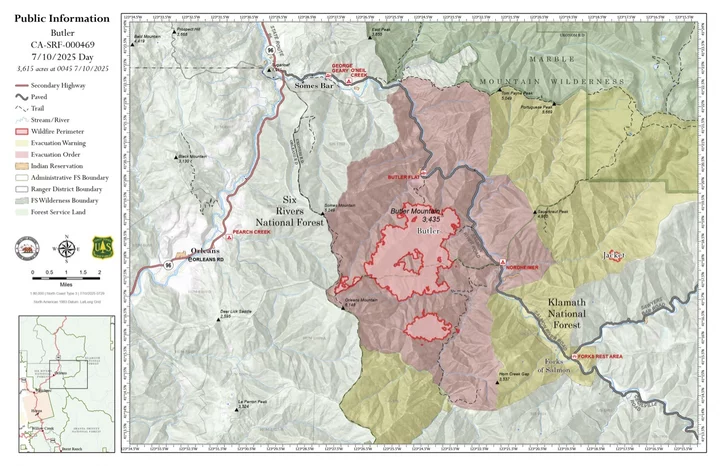

(VIDEO) FIRE UPDATE: Butler Fire Explodes to 3,615 Acres With No Containment

LoCO Staff / Thursday, July 10 @ 10:50 a.m. / Fire

Video: Six Rivers National Forest

###

Press release from the Six Rivers National Forest:

Butler Fire Acreage: 3,615

Butler Fire Containment: 0%

Red Fire Acreage: 113

Red Fire Containment: 25%

Operational Update: California Team 1 (CA-CIMT 1) is expected to assume command of the Orleans Complex by Saturday.

• Butler Fire: Today the Butler and Nordheimer Structure Groups will put in more hoselay and set up equipment to protect communities and infrastructure. Crews will continue to assess and prep the Salmon River Road between Butler Creek and Nordheimer Creek. To the east and south, crews will continue to scout Forest Road 10N04, lines from the 2024 Boise Fire, lines in the Horn Gap area, as well as the fire within the Nordheimer drainage. Crews near the Nordheimer community will also assist with structure protection across the Salmon River.

• Red Fire: The Red Fire is estimated to be approximately 113 acres. Smokejumpers and crews are making good progress on putting fireline around the fire. Though there is some complexity in putting line around the left flank of the fire, crews have managed to raise fire containment by 25%. Cultural resource specialists and resource advisors are working in coordination with responders on the ground.

Evacuations:

• Butler Fire: Siskiyou County Sheriff’s Office has evacuation warnings and orders in place for the Butler Fire. An Evacuation Order has been issued for zones SIS-1703 (no residents), SIS-1704 (Butler Creek, Lewis Creek, Bloomer Mine residents and Nordheimer Campground), SIS-1803-A (no residents) and SIS-1707-A. Zone SIS-1707-B remains under a Warning, but residents are advised to be prepared as the situation evolves.

• Red Fire: No evacuations or structures threatened.

Closures:

• Butler Fire: Crews may be working along Salmon River Road and impacts from the fire are likely, including smoke and falling debris. Residents should be prepared for potential traffic controls or temporary closures along the road between Butler Flat and Nordheimber Campground. Nordheimer and Oak Bottom Campgrounds are both closed.

• Red Fire: No closures or road impacts.

Weather & Fire Behavior: In the words of incident meteorologist James White, the area is defined as a “land of inversions.” This morning the relative humidities were in the 80s in the lower slopes and valleys and in the 30s-40s in the upper slopes and ridgelines. This is good for fuel moisture recovery and fire behavior. However, as temperatures continue to rise in the coming days and relative humidities decrease, fire behavior will be more active. Wind in the area is expected to be terrain controlled and mostly expected to be be localized and weak. Along the Salmon River as well as ridge tops(north) gusts up to 20 mph may be possible.

Fire Safety & Prevention: Reduced visibility due to smoke as well as possible falling debris along roadways could impact driving safety in the area. Drivers are advised to use caution and check www.roads.dot.ca.gov for any closures before planning trips to the area. Watch for increasing firefighter traffic as the incoming team and additional resources arrive in the area.

Help firefighters by being careful with anything that can spark a wildfire! Going into a hot, dry summer weekend, be careful in the forest and avoid driving or parking on dry grass. Please report suspected wildfires by calling 911.

###

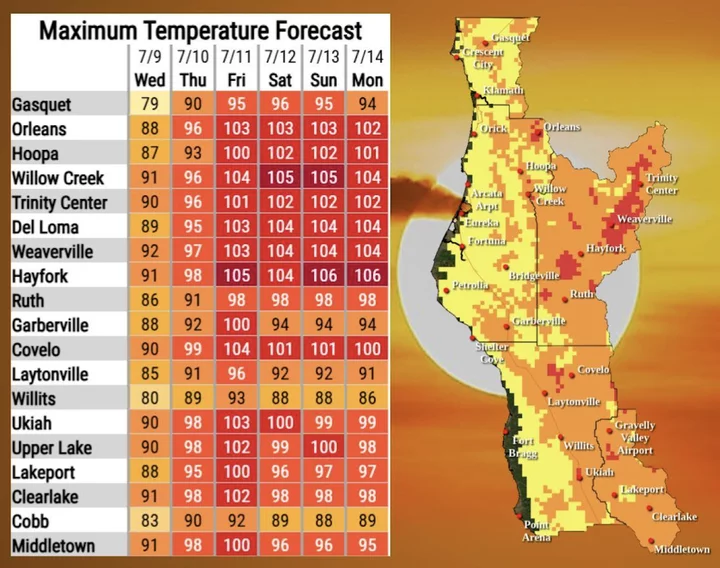

Click to enlarge.

This Weekend: Hot

LoCO Staff / Thursday, July 10 @ 8:01 a.m. / How ‘Bout That Weather

Higher Premiums and Lost Coverage: How Trump’s Budget Will Change Health Care in California

Ana B. Ibarra and Kristen Hwang / Thursday, July 10 @ 7:21 a.m. / Sacramento

A medical worker pushing a bed through the corridors of Hazel Hawkins Memorial Hospital in Hollister on March 30, 2023. Photo by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

The new federal budget signed into law by President Donald Trump is expected to raise some health care insurance premiums and force millions off coverage, reverberating the most in lower-income families and communities that are already struggling.

Trump’s new budget reduces spending for Medicaid — called Medi-Cal in California — by $1 trillion over the next 10 years. These savings would happen in part because new requirements will result in people falling off coverage.

In addition, some people enrolled in Covered California, the state’s marketplace for subsidized health plans, can expect new rules and higher costs, which means more people will be unable to afford the insurance.

Over the next 10 years, the federal changes are estimated to cost the state $28.4 billion and result in 3.4 million Californians losing coverage, according to an estimate from Gov. Gavin Newsom and state health officials.

Less federal funding for Medi-Cal means California will have to make decisions on who is covered and which services are offered. That loss of coverage could be a big blow to California, where lawmakers like to boast about having one of the nation’s lowest uninsured rates.

Alex Rossel, CEO of the community clinic Families Together of Orange County, says as people lose coverage, they’ll get sicker and be left in debt. “All that hard work that clinics have been doing to help people manage their chronic illnesses… is going to be in jeopardy,” he said.

And the effects of these changes could be felt beyond people enrolled in Medi-Cal and Covered California as clinics and hospitals warn that their financial challenges are likely to be exacerbated. Some may have to reduce services or close their doors.

Here are five things to know about how the new federal budget will affect Californians:

Some Medi-Cal enrollees will have work requirements and co-pays

Most notably, the new law requires adults ages 19 to 64 to report at least 80 hours a month of “community engagement,” which could be employment, school or volunteer work.

People who fail to do so will no longer qualify for Medi-Cal. Parents of children 13 and under and people with mental and physical disabilities will be exempt from the work requirements. The new requirement takes effect Dec. 31, 2026, although states could choose to start sooner.

The Urban Institute estimates that this rule alone could force up to 1.4 million Californians off their Medi-Cal insurance in the first year of implementation — not necessarily because they don’t work, but because filing paperwork is likely to pose a challenge for many enrollees. Enrollment counselors say some workers, such as housekeepers and gardeners, don’t have regular paychecks or documentation to prove their employment.

This same group of adults will have to reapply for coverage every six months, instead of once a year. And those who earn more than $15,060 a year, starting in October 2028, may have a co-pay of up to $35 per visit — although the exact amount will be up to states. Some visits will be exempt, such as prenatal and primary care, pediatric care and emergency room visits. (A single adult qualifies for Medi-Cal with an annual income of up to $21,597.)

Higher premiums for Covered California

One of the most significant changes is by omission: The Republican-led Congress opted to not renew some Affordable Care Act subsidies that will expire at the end of this year.

Nearly 90% of Californians who purchase insurance through Covered California, the state’s Affordable Care Act insurance exchange, receive financial assistance from federal subsidies that help lower monthly premiums.

On average, for all enrollees, premiums are expected to increase by 66%, or $101, per month starting next year. Lower-income people will see the biggest premium increase because they receive more subsidies, said Covered California Executive Director Jessica Altman.

Those making less than 400% of the federal poverty level (about $60,240 per year for an individual) are projected to pay an average of $191 more monthly, according to Covered California data.

More than 170,000 middle-income enrollees will lose financial assistance entirely.

Other changes made in Trump’s sweeping budget and policy bill include the elimination of automatic renewal, more income verification requirements and limiting special enrollment periods. The groups most likely to forego coverage because of administrative barriers are those who are young and healthy, Altman said.

Combined, the added enrollment complexities, along with higher out-of-pocket costs, are expected to drive nearly 600,000 Californians off of coverage, according to Covered California projections.

Hospital cuts could impact everyone

When people lose coverage, they are likely to skip routine care; they wait until they are very sick and then visit an emergency room. And without insurance, most people cannot afford to pay their hospital bills.For hospitals, more uninsured patients means less compensation. The law also adds new restrictions on provider taxes that states levy on hospitals and insurers to draw down matching federal funds to help pay for Medi-Cal. Hospitals receive payments from the revenue generated by these taxes that help them fill the gaps from traditional reimbursement.Rural and community hospitals that care for a large share of low-income patients enrolled in Medi-Cal may have an especially difficult time absorbing the losses, so they may have to cut services, reduce staff or close, hospital leaders say.“Hospitals will be forced to make difficult decisions, and access to vital health care services will be jeopardized for all Californians — not just those who rely on Medi-Cal for their health care coverage,” Carmela Coyle, the president of the California Hospital Association said in a statement. In a recent press briefing, Newsom noted that a number of hospitals in California have been struggling for some time. In 2023, California rolled out $300 million in interest-free loans to bail out 17 distressed hospitals. The state, currently dealing with a budget deficit, would have a harder time helping hospitals again.“Those distressed hospital loans came at a time of abundance. Those distressed hospital loans came at a time when we had much more stability with state funds and federal funds, and they were 3x the request for support,” Newsom said.

A funding ban for Planned Parenthood

Effective immediately after Trump signed the bill, Planned Parenthood clinics were banned from receiving federal Medi-Cal payments. Three days later, a federal judge temporarily blocked the funding cut after Planned Parenthood sued. But as the litigation plays out, advocates say the move could be financially devastating to clinics across the country. In California, a million people use Planned Parenthood clinics each year, and Medi-Cal makes up 80% of its patients.Federal law already prohibits the use of federal dollars to pay for abortions except in extremely limited instances. But Planned Parenthood does much more than that for patients. While it’s the largest abortion provider in the state, abortions account for less than 10% of its services. Contraceptives, sexually transmitted infection testing and treatment and check ups account for the vast majority of patient visits.California Planned Parenthood clinics stand to lose more than $300 million, jeopardizing their ability to remain open. The national Planned Parenthood association estimates that 200 clinics across two dozen states are at risk of closure.All clinics are open and taking patients, said Jodi Hicks, affiliate CEO and president. But the funding cuts could amount to a de facto abortion ban because in many California communities, Planned Parenthood is the only provider that performs abortions.“People should be angry,” Hicks said. “We will fight back with every tool that we have to ensure that patients are able to be seen at our health centers, but the damage of defunding an entity that has such a large footprint in California is deep.”

Some kids will lose health care and food stamps

The vast majority of health and social services cuts in the federal budget are aimed at adults, but experts say kids will suffer as well. That’s because many of the changes implemented for adults, like work requirements and more frequent income eligibility checks can impact the eligibility of the entire family.

“There are a lot of ways that kids can fall through the cracks,” said Mike Odeh, senior health policy director for Children Now.

About 5.5 million children in California, half of the state’s youths, use Medi-Cal. The state insurance program also pays for some school-based health services, such as counseling and speech therapy.

One of the biggest health cuts targeting children specifically restricts eligibility for the Children’s Health Insurance Program to legal permanent residents, meaning other immigrant children with temporary legal status such as visas or refugee status could not qualify. California already provides health care for all children regardless of immigration status, but the federal prohibition means the state will have to pay more if it wants to continue covering them.

On top of the Medi-Cal cuts, the budget bill makes significant changes to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, often referred to as food stamps. It institutes stricter work requirements for many adults including veterans and parents of teenagers, ties future spending to inflation and shifts more of the cost-sharing onto states. Similar to the immigration requirement for children’s Medi-Cal, food stamp eligibility will also be restricted to legal permanent residents.

Newsom’s office estimates that 735,000 people will lose food stamps. Early estimates from the Urban Institute project that 3.1 million California families will lose at least some of their food assistance. About a third of all newborns in California are enrolled in food stamp programs, according to the Public Policy Institute of California.