Arise, Da’ Yas! The Rechristening of 20/30 Park Headlines Tomorrow’s Eureka City Council Agenda

Hank Sims / Monday, Dec. 5, 2022 @ 1:19 p.m. / Local Government

File photo: Andrew Goff.

Now, we’re aware that at least a few people aren’t in favor of the big rebranding of 20/30 Park that the Eureka City Council is looking to finalize at its Tuesday night meeting. They carry some sort of torch for that civic club of yore which built the current park – an association of young men in their 20s and 30s that apparently made a point of doing good deeds around town, way back when. And that’s fine. History is important.

But just on a practical level: Was there ever a park in more dire need of a reputational refresh? In case you weren’t aware, 20/30’s image is not good. There was a time, not long ago, when its name conjured every manner of shady behavior. Things seem to have quieted down a bit lately but the stigma remains, and it probably doesn’t help that since the 20/30 Club ceased to exist many, many decades ago, the park’s name just strikes the casual onlooker as some sort of … blank. Two numbers. It sounds, more than anything, like a police code.

Which is a shame, because not only is the park located on the city’s heavily populated and less well-to-do West Side, where there are lots of kids who could do with a boost in neighborhood pride, but the park itself has some cool features that are about to get a lot cooler. The city has obtained big grant funds to renovate the place, which will include all-new playground equipment, extra amenities (Roller hockey! Futsal!) and an upgrade for the park’s neat old baseball field.

City government thought that maybe this would be a good time to redo the name of the park, too, and after a few rounds of polling the citizenry they decided that the public liked the idea. Working with the Wiyot Tribe, the city came up with a shortlist of Soulatluk names that might serve, and after more polling and a pass through the planning commission they settled on “Da’ Yas,” in honor of the cypress trees that populate the park. “Da’ Yas” means “where the cypresses are.”

And so

the council is expected to formalize Da’ Yas Park to much fanfare

and no doubt some disgruntlement Tuesday night, in what will be the evening’s showcase item. Read

the staff report here. Also on the agenda, earlier in the evening

and on the consent calendar, is a resolution that’ll permit the

city to buy all the new playground equipment from a single vendor, to

the tune of about $600,000. That equipment will contain some

specialty gear, including the big swan egret that’ll be the playground’s

showpiece. The staff

report for that is here, and a bid from a Santa Rosa company

called Ross Recreation Equipment

can be

found here. [CORRECTION: Yes egret, not swan. Thanks to the commenter below.]

Above: New park design. Below: The big egret.

###

What else is on the agenda, you ask? The council will look to finally finalize that sewer lateral ordinance that Izzy wrote about a few weeks ago. They’ll talk about updating some local building codes to comport with new state law. (Staff report here.) They’ll think about refinancing some old wastewater bonds, which should amount to a million dollars in savings according to the staff report, which can be found here.

Since it’s on the consent calendar, the council will likely approve the purchase of eight new “fully outfitted” Chevy Tahoes to serve as police vehicles, at a cost of $550,000. According to the staff report – find it here! — the purchase will be part of a new “Assigned Vehicle Program” developed by the Eureka Police Department, in which cop cars will be assigned to some specific officers, rather than placed in a car pool which all the police draw from willy-nilly. The cops would also take their car home on the days in which it’s assigned to them. Here, let that staff report explain it:

The purpose of the AVP is to improve department efficiency in response to critical incidents, accountability, and vehicle longevity at the Police Department. Officers have expressed interest in an AVP for some time now as a way in which to improve overall morale in the department. This program will also create more accountability for vehicle use and care among department members. Furthermore, by implementing the AVP, vehicles will not be driven as often and the longevity of the City’s fleet will improve.

The AVP will involve a patrol vehicle assigned to a pair of patrol officers working opposing weekday and weekend shift assignments. This program will allow officers from each team, based on a lottery, to be assigned a specific patrol vehicle for the duration of the calendar year. Additional vehicles would be maintained as pool cars, to be utilized by officers working overtime, or if their assigned vehicle is unavailable or in need of maintenance.

Information gathered from other agencies by the Police Department indicates that assigned vehicle programs elsewhere have resulted in higher morale, better cared for vehicles, and better presence in the community, with assigned vehicles visible when travelling to and from work or parked at officers’ residences.

###

Separated at birth? Eureka Mayor Susan Seaman beams at Kamisu mayor Susumu Ishida, himself beaming at Eureka, at the 2019 dedication of Kamisu Park. File photo: Andrew Goff.

Apart from those things, the council is going to hear a whole bunch of reports and updates and special presentations about various stuff cooking in the community.

The California Fishermen’s Marketing Association will be on hand to talk about what they’re up to, and — presumably — to outline some of the fisherfolks’ concerns about offshore wind energy.

The Eureka Youth Council — a cool, kinda shadow City Council populated by teenagers — will show and give a presentation, and hopefully they will tell the actual council about everything they’re doing wrong.

Mayor Susan Seaman will have a couple of updates from the Humboldt Count Library and the Kamisu Sister City Project. And, to cap off the evening, City Manager Miles Slattery will give the council an update on the city-run Little Saplings preschool program.

Get hype! The Eureka City Council meets at 6 p.m. Tuesday, at Eureka City Hall, there at the corner of Fifth and K streets. The full agenda, including instructions on how to Zoom in to the meeting remotely, can be found at this link.

BOOKED

Today: 8 felonies, 12 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

Singley Ln Onr / Mm101 N Hum 66.10 (HM office): Trfc Collision-No Inj

3924 Mm101 S Hum R39.20 (HM office): Traffic Hazard

SR299 / Acorn Ln (HM office): Trfc Collision-No Inj

Sr3 / B Bar K Rd (RD office): Traffic Hazard

Mm199 N Dn 33.40 (HM office): Trfc Collision-No Inj

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Lightning-Sparked Fires Spread Across North Coast Forests; Crews Responding Across Rugged Terrain

Governor’s Office: TOMORROW: Governor Newsom to announce $750 million tax credit for film and TV made in California

RHBB: Rumors of ICE Presence in Garberville Dispelled—State Parks Training Confirmed

Governor’s Office: National Guard firefighters finally back to work — but Trump’s militarization of LA has pulled cops from the street and teachers out of classrooms

Man Wanted for Robbing Salvation Army Bell Ringer at the Mall Arrested After Stealing Tip Jar at a Nearby Business, Eureka Police Say

LoCO Staff / Monday, Dec. 5, 2022 @ 11:37 a.m. / Crime

From the Eureka Police Department:

On December 3, 2022, just before 6 p.m., officers with the Eureka Police Department responded to the 3300 block of Broadway for the report of a robbery that just occurred outside of a major retail store. The victim, a 65-year-old Salvation Army Bell Ringer, was handed a demanding and threatening note by an unknown male. The male then removed the red kettle full of donations and fled into the nearby greenbelt.

Officers reviewed surveillance provided by store security and were able to immediately identify the suspect as 32-year-old Dennis Scarella of Castro Valley. Scarella had been contacted by officers less than an hour prior. Officers searched the greenbelt but were unable to locate Scarella. An arrest warrant was issued and broadcasted to surrounding agencies.

On December 4, 2022, at about 4:10 p.m., officers responded to a restaurant on the 3000 block of Broadway for the report of a stolen tip jar. Employees provided officers with an image from surveillance. The suspect was identified as Scarella. After a brief search through the surrounding greenbelt, Scarella was taken into custody without further incident.

Scarella was transported and booked into the Humboldt County Correctional Facility for robbery. Additional theft related charges are still under investigation.

Five-Year-Old Eureka Girl Accidentally Shot by Father, Says EPD

LoCO Staff / Monday, Dec. 5, 2022 @ 11:32 a.m. / News

Eureka Police Department press release:

On December 3, 2022, at about 10:30 p.m., officers with the Eureka Police Department responded to St. Joseph Hospital’s Emergency Department for the report of a 5-year- old juvenile female who had been shot in the foot by her father. The family self-transported the juvenile to the hospital and hospital staff notified law enforcement.

Based on the initial investigation, it appears the incident occurred in the family home located near W Grant and California Streets. It is reported the juvenile was shot in the foot when she jumped onto her father’s lap while he was cleaning his gun.

The Eureka Police Department Criminal Investigations Unit responded and assumed control of the investigation. This is an ongoing investigation and no arrests have been made. The juvenile is in fair condition and is recovering.

ACLU Files Civil Rights Complaint Against Loleta Elementary Alleging Discrimination Against Native and Disabled Students

Ryan Burns / Monday, Dec. 5, 2022 @ 10:13 a.m. / Education , Tribes

Loleta Elementary School. | Photo by Andrew Goff.

###

For the second time in less than a decade, the ACLU of Northern California today filed a civil rights complaint on behalf of the Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria alleging repeated acts of discrimination by Loleta Elementary School employees against Native students and students with disabilities.

According to the complaint, district employees, including at least two teachers, have regularly subjected Native students to verbal harassment and excessive discipline beyond what’s meted out to non-Native students. This pattern of disparate treatment “directly reflects discriminatory racial intent,” the complaint says.

As evidence, the filing cites firsthand accounts from parents and students and includes, as an exhibit, a recent report regarding a third-party investigation commissioned by the district in response to complaints from a parent. That investigation resulted in sustained allegations of discrimination against disabled students; failure to implement a student’s individualized education program (IEP) as required by law; and one teacher repeatedly demeaning and shaming students in class.

“The findings are damning and reveal a pattern of racial hostility,” said Carmen King, a communications strategist for the ACLU of Northern California. “These [findings] include multiple examples over the last year that Loleta Elementary staff has used racial slurs in their interactions with Indigenous students.”

The ACLU’s complaint, which was filed with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights in San Francisco, comes nine years after that same office launched an investigation into the Loleta Union School District over very similar allegations made by the Wiyot Tribe, with support from the Bear River Band.

The subsequent inquiry found substantial evidence that the district had created a hostile environment for Native American students, disciplining Native students more harshly than others and failing to provide legally mandated services for Native students with disabilities.

This new complaint says these kinds of discriminatory behaviors have resumed at Loleta Elementary School.

“The case is centered on how the Loleta School District has denied Indigenous students, including disabled students, equal educational opportunities as required by the law by ignoring serious and repeated acts of discrimination and harassment,” said Linnea Nelson, senior staff attorney for the ACLU of Northern California.

In a phone interview on Friday, Nelson said parents of impacted students have repeatedly raised these issues with administrators and staff, “and they have, unfortunately, been met with indifference, inaction and, in some cases, retaliation,” she said. “The Bear River Band tribal council felt that a very strong and serious response was needed to support those families and those students who are brave enough to come forward and really expose what has been happening in Loleta Elementary School classrooms over the last several months.”

One of those parents is Sarah Sand, who told the Outpost that her son was subjected to a variety of discriminatory behavior last school year, when he was in fifth grade. A Native American student, Sand’s son has been diagnosed with ADHD and sensory processing disorder, conditions which can manifest in fidgeting, wiggling in his seat or blurting things out when it’s not his turn to speak.

Her son’s IEP calls for a one-on-one aide, extra breaks and alternative testing methods, but Sand said her son’s teacher, Heather Nyberg-Austrus, failed to implement them.

“There were many accommodations that could have made his life and his time easier, and she just refused to make them,” Sand said.

She said Nyberg would regularly call her at work to say her son was acting up so she should come pick him up. But when she talked to staff and administrators, she got conflicting reports. On the last day of school before Christmas break last year, she got another call to come get her son, but when she arrived at school a few minutes later she was told that staff had lost track of him.

“And they said, ‘Well, he’s probably somewhere,’” Sand recalled. “And it was that moment when I realized that there was a big problem, because it was easier for them to lose my child than it was to implement his IEP or deal with him.”

She also heard disturbing anecdotes about Nyberg using racially coded language — referring to a group of Native students as a “gang,” for example, while referring to non-Native kids in more benevolent terms.

This past June Sand filed a complaint against the district and several staff members pursuant to the California Department of Education’s Uniform Complaint Procedures. She also reached out to the ACLU.

“It felt like the right move,” she said. “I felt that something was wrong, but I couldn’t quite figure out what it was. I knew his IEP wasn’t being implemented. I knew that they were just pacifying me. … That was when I said, you know, we have to talk to somebody. This has to stop.”

An investigation was conducted by the Whitestar Group, a neutral, private investigation firm based in Santa Rosa, and just last month Sand received a letter from Loleta Superintendent/Principal Linda Row summarizing the findings.

The evidence, including witness testimony, established that Nyberg had locked students out of class and excluded numerous students, including Sand’s son, from attending field trips as punishment for behaviors related to a recognized disability, according to Row’s letter. The investigation also found that her son’s IEP was not properly implemented and that Nyberg inappropriately raised her voice to Sand’s son and other students.

“Every witness provided numerous examples of [Nyberg] ‘screaming,’ ‘yelling’ and raising her voice to both students and other staff members … ,” Row’s letter says. “The school psychologist and several other witnesses observed negative impacts on students such as crying, saying [Nyberg] didn’t like them, and avoiding [Nyberg’s] class.”

Row’s letter went on to say:

The evidence supported the conclusion that, during the 2021-2022 school year, [Nyberg] shamed a specific student in front of his classmates by asking if he took his medication that day.

The evidence also supported the conclusion that, in July 2022, when a student, whose IEP calls for breaks, returned to class after a break, [Nyberg] asked the student’s aide, “Now where was he?” The aide responded, “He took a short break.” [Nyberg] then replied in front of the whole class, “A break from what, laying his head down on the table all morning?”

The district concluded that Nyberg had engaged in antagonistic, derogatory and discriminatory behavior toward students, bullying them to the point where they dreaded going to her classroom. Nyberg’s behavior violated several district policies, and Row’s letter to Sand said, “The District will be taking corrective action and informing [Nyberg] of District expectations.”

Sand wasn’t impressed.

“What does that mean?” she said. “That doesn’t mean anything to me. Our children are still being harmed. The teacher is still teaching.”

Sand’s outrage is still raw, and she grew emotional when talking about the psychological impacts on her son.

‘The honest, hard truth is that my son experienced bullying from his teacher, from someone that I trusted to keep my child safe at school.’ —Sarah Sand

“The honest, hard truth is that my son experienced bullying from his teacher, from someone that I trusted would keep my child safe at school — an authority figure — and she abused that trust and she broke that trust and she made him feel like he was small, like he couldn’t function properly because of his disability.”

She said that at one point last school year, her son became so despondent that he drank a large amount of mouthwash, hoping it would make him sick enough to solve all his problems. Sand believes it was a suicide attempt.

“And I have been struggling with that ever since because he did not — this didn’t need to happen,” Sand said. “It didn’t need to happen at all. And I know my son is not the only child suffering.”

The ACLU complaint says that’s clearly true, and it cites several examples involving Nyberg as well as Loleta Elementary’s seventh-eighth-grade teacher, Mary Gustaveson.

“In November 2022, Ms. Gustaveson screamed so loudly at an Indigenous student that other students were afraid Ms. Gustaveson was going to hit the student,” the complaint says. It also alleges that Loleta Elementary employees have used racial slurs towards Indigenous students and disciplined Indigenous students more harshly than their non-Native peers.

The most egregious example of Loleta staff members’ racial hostility, according to the complaint, occurred when Nyberg, who is white, repeatedly used the “N-word” in the classroom while trying to explain to students that racial slurs are okay when used by people within the affected group — two Indigenous students calling each other “Indian giver,” for example — but not okay when used by people outside the group.

“Multiple students in the class then replied to Ms. Nyberg that the ‘N-word’ was a bad word and always racist,” the complaint says. “Ms. Nyberg stated that her use of the ‘N-word’ in that conversation was not racist because no one in the classroom was Black and she was not directing the word at anyone.”

A footnote explains that Nyberg didn’t say “the N-Word” but instead used the actual word. “Since this word is one of the most offensive racial slurs in the English language, this complaint instead refers to it as the ‘N-word,’ but Ms. Nyberg used the full word throughout this exchange,” the footnote says.

Numerous students were extremely upset by this incident, the report says, and it alleges that Nyberg has also used racially-coded, derogatory language to refer to Indigenous students and routinely prohibited Indigenous students from sitting in the seat closest to her desk, which many students view as a “privileged seat.”

The complaint says Nyberg’s offensive comments date back at least four or five years, including things she said during an all-school meeting to acknowledge that Loleta is on ancestral Wiyot land.

“Ms. Nyberg spoke up in a very oppositional tone and said, ‘I’m a fifth-generation Ferndalian,’ strongly implying that her family has as much right to the land as the Wiyot people,” the complaint says, adding that this claimed entitlement “is deeply disturbing given that, approximately five generations ago, white settlers in Humboldt County engaged in massacres and other genocidal acts against local Indigenous communities, including the Wiyot people.”

The complaint cites examples of discriminatory behavior from other staff members, including Superintendent Row, saying she and the LUSD board of trustees “have acted with deliberate indifference to racial discrimination by failing to effectively respond to specific complaints of discrimination, retaliation, and verbal racial harassment against Indigenous students.”

As an example, the complaint says that the board responded to concerns about Nyberg’s use of the “N-word” with vague suggestions of “weak measures,” such as sending her to an unspecified training at some point in the future.

# # #

Parents like Sand hope that the ACLU’s complaint will produce more tangible results. Nelson said the complaint filed by her organization nine years ago did seem to improve matters — for a while, anyway.

In 2017, the Loleta Union School District entered into a voluntary resolution agreement with the U.S. Department of Education, promising to engage with expert consultants, identify the root causes of discrimination, develop a corrective action plan and submit numerous progress reports.

The district eventually hired a psychologist, Sandy Radic-Oshiro, to serve as school climate director, a role that provided students with essential support, Nelson said.

“Her time, as I understand it, was funded through the Humboldt County Office of Education,” she explained. However, the school climate director position is no longer being funded, and Radic-Oshiro left the district this past June. “And I think that has had a significant negative impact on the district implementing the provisions of the previous settlement agreement with the federal government,” Nelson said.

The Bear River Band is requesting government-to-government consultation with the district — through the Office of Civil Rights — to discuss a new proposed resolution agreement. Nelson said the ACLU and the Bear River tribal council felt that filing a second complaint was necessary to underscore the gravity of the situation.

“That kind of racism affects students’ visions of themselves and their futures,” Nelson said, “and being subjected to racist remarks and stereotypes at school negatively impacts educational outcomes for Indigenous youth.”

Darrell Sherman can attest to the long-term harm caused by discrimination from a respected role model. A tribal council member and social worker who formerly worked as the tribe’s assistant director of social services, Sherman grew up in Loleta and attended the elementary school. In a phone interview last week he remembers having a strong bond with his teachers.

“I graduated from Loleta in ’96, and we had so much rapport with them because we had a lot of tenured [teachers],” he said. “Like, all the teachers knew your uncles and aunts and cousins, and some even taught your parents.”

He doesn’t remember hearing any racist remarks from teachers, but he did once feel betrayed by his Little League coach, who he considered one of his best friends. One day while he was pitching in a game, Sherman kept making a mistake on the mound, dragging his back foot off the rubber plate in what’s called a balk — a violation that allows the batter to take a base.

His coach approached the mound, and while on his way he made a declaration loud enough to be heard by everyone nearby: “Oh, don’t worry about it; he’s Indian,” Sherman recalled.

He was too wrapped up in the stress of the game to think much about the comment in the moment, but the remark stayed with him for years, this offhand suggestion that he was somehow deficient because of his ethnicity.

“I think of the situation and the experience that I had and the long-lasting negative effects,” Sherman said. “It’s just generations, you know?”

Reached by email on Friday, Loleta Union School District Principal/Superintendent Linda Row said she did not have any comment since she had yet to receive a copy of the complaint. The Outpost forwarded a copy to the district Monday morning. We’ll update this story if and when the district responds.

###

DOCUMENT: OCR Complaint Re: Loleta Union School District

###

Here’s a press release from the ACLU of Northern California:

Today, the ACLU Foundation of Northern California filed an administrative complaint with the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights on behalf of the Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria regarding repeated acts of discrimination against Native American students and students with disabilities in Loleta Union School District.

The complaint reveals troubling patterns of racial hostility and cites multiple occasions over the last year that Loleta Elementary staff has used racial slurs and racially coded language in their interactions with Indigenous students. Parents of Indigenous students who have come forward to raise these issues with school administrators have been met with deliberate indifference and, in some cases, active retaliation from school staff. The failure to respond to complaints of discrimination and harassment is in opposition to the district’s own required policies and procedures.

The complaint also details repeated failures on behalf of school staff to make reasonable modifications to avoid discriminating against students with disabilities. Rather than modifying disciplinary policies and practices as required by the Americans with Disabilities Act, Loleta Elementary staff routinely punish disabled students for behaviors arising from their disabilities. Students who exhibit behaviors that are manifestations of their disabilities are often removed from classrooms and denied critical learning time.

Indigenous students with and without disabilities face disproportionately higher rates of exclusionary discipline, chronic absenteeism, and lower academic outcomes than their non-Indigenous peers. These disparities are particularly egregious in Humboldt County. A 2020 report authored by the ACLU titled, Failing Grade: The Status of Native American Education in Humboldt County found that Indigenous students in Humboldt County, including in Loleta USD, face vast disparities in academic outcomes. These negative outcomes are a direct result of systemic failures that cause Indigenous students to feel disengaged and unwelcome at school, such as bullying and racially hostile school environments; disparate use of disciplinary practices such as suspension, expulsion, and referrals to law enforcement; and failure to provide school-based student supports, including culturally relevant school-based mental health professionals.

“Explicit and implicit racism affects students’ vision of themselves and their futures. Being subjected to racist remarks and stereotypes at school negatively impacts educational outcomes for our native youth, said Darrell Sherman, Council Member of the Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria. “We need to tell kids they are doing a good job; tell them they are going to succeed—and treat them accordingly. We all have a role in building up and protecting the youth in our community.”

Previously, the Humboldt County Office of Education provided a part-time School Psychologist and School Climate Director at Loleta Elementary to help to address discrimination experienced by Indigenous families and to create a more inclusive school culture. Unfortunately, the District failed to fill that position when it became vacant earlier this year. The absence of an effective School Climate Director has exacerbated much of the discrimination and harassment experienced by Indigenous students and their families.

“With the departure of the previous Superintendent and previous School Climate Director, the situation at Loleta Elementary has rapidly spiraled out of control, and the district is failing to take reasonable action to remedy or stop ongoing serious legal violations,” said Linnea Nelson, Senior Staff Attorney at the ACLU Foundation of Northern California.” Indigenous students and students with disabilities are suffering at Loleta Elementary School because of employees’ discrimination against them. Robust corrective action is urgently needed.”

“The Bear River Band is committed to challenging historic inequities on behalf of its members and all Indigenous students,” said Josefina Frank, Chairwoman of the Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria. “Remedying unlawful discrimination is essential to provide Indigenous students at Loleta with equal educational opportunities so they can further their education and achieve professional success.”

Is California’s Beleaguered Jobless Benefits Agency Ready for a Recession?

Grace Gedye / Monday, Dec. 5, 2022 @ 8:07 a.m. / Sacramento

The headquarters of California’s Employment Development Department in Sacramento. The agency says it’s made improvements that have made it better equipped to issue employment benefits if the economy goes south. Photo by Rahul Lal, CalMatters

A cascade of tech layoffs, the strain of inflation and news of potentially recession-inducing decisions from federal bankers could spell tough economic times ahead.

If more people are laid off, more Californians will turn to unemployment benefits to help them afford the basics while they look for a new job.

It’s a process that buckled under the pressures of the pandemic. Residents sometimes waited months for benefits from the state’s Employment Development Department, dialing the department hundreds of times. On top of that was a string of fraud scandals: Claims came from ‘unemployed’ infants and children and according to prosecutors, benefits were paid to tens of thousands of inmates in jail and prison, who are ineligible. The vast majority of the fraud was in temporary, federally funded pandemic aid programs.

The situation has since improved. But how will the system hold up if there’s a recession?

Thanks to “the level of testing that the pandemic put us through, we are in such a strong position to weather a typical economic contraction,” said Gareth Lacy, communications advisor at the department.

But not everyone is convinced. “There have been some major improvements,” said Daniela Urban, executive director of the Center for Workers’ Rights. “But I think we’re not at the point where if a major crisis hit the unemployment system again, the system would be able to function as it should.”

A recession would probably look different than the shocking early months of the pandemic, when claims for new benefits jumped tenfold from February to March of 2020, according to department data. One point of comparison: There were 20 million claims for unemployment benefits during the pandemic and 3.8 just million during the Great Recession, according to Lacy. And during the pandemic, the challenge for the department wasn’t just dealing with the surge of claims; it also had to implement new federal aid programs.

The incredible wave of people applying in a matter of weeks was “extreme” says Till von Wachter, an economics professor at UCLA. Normal recessions are more gradual, he said, so the number of claims the department has to process per week would likely be lower. “They just went through trial by fire,” von Wachter said. He’s optimistic that the department would be able to better deal with a recession.

But, if the agency struggles to keep up with the demands of a recession, it wouldn’t be the first time. In the wake of the recession that began in 2008, reports emerged that checks were delayed due to outdated computers, and exasperated workers were met with busy phone lines.

Inside the department’s recession plan

In 2021, state lawmakers required the department to come up with a recession plan; the result is a nearly 90-page report.

One change, the report explains, is that the department created a new team tasked with forecasting unemployment benefit-related workloads and figuring how many staff will be needed. The report also details how the department will adapt if the unemployment rate reaches specific levels. California’s unemployment rate is currently around 4%, but if, for example, it ticks up to 6%, the plan includes authorizing overtime, reducing vacation slots during peak periods, and limiting the approval of part-time requests. If it reaches 8%, the department would hire additional staff and “deploy retired annuitants.” If it reaches 12%, it’s time to call in the contractors.

The report says pulling all this off is challenging because federal funding for unemployment benefit administration is tied to an actual — not anticipated — workload.

Given “the level of testing that the pandemic put us through, we are in such a strong position to weather a typical economic contraction.”

— Gareth Lacy, state Employment Development Department

The agency has made some other changes that could smooth the process of getting benefits.

For Californians whose primary language is not English, expanded multilingual services should make it easier to navigate the system. “Individuals who are not fluent in English face insurmountable barriers to receiving assistance,” found a September 2020 ‘strike team’ report. In a February settlement with several advocacy groups, the department agreed to:

- Provide real-time spoken and signed language services for workers in any language they need

- Add dedicated phone lines for Korean, Tagalog and Armenian speakers in addition to existing lines serving Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, and Vietnamese speakers

- Translate all important unemployment benefits documents in the top 15 non-English languages used in the state by the end of 2022.

A new section of the unemployment benefits website now provides forms and other information translated into eight languages, plus simplified Chinese. The expansion came after a legislative push to add multilingual services for unemployment benefits.

Another recent change addresses what happens if you start getting benefits, and then your eligibility is called into question. In the past if, in the course of filling out forms to prove your ongoing eligibility, you indicate that you worked one day, or were sick one day – two things that could disqualify you from receiving benefits – the department would stop sending payments until it determined whether you were still eligible, which could require an interview, said Urban.

“At the height of the pandemic, (the department) was so behind the determinations (that) people were waiting 15, 16, or more weeks for these determinations,” and in the meantime, they weren’t receiving any benefits, Urban said. Now, if the agency can’t determine whether you’re eligible within 14 days, it will keep paying benefits while they sort out the issue, Urban said.

There have been other customer service tweaks over the past couple of years, including adding a call-back feature on call center phone lines so that people don’t have to wait on hold, improving the mobile phone version of the website, and enabling claimants to upload documents, rather than physically mail them in, according to the department.

The department has also begun a multi-year modernization effort, dubbed EDDNext, aimed at improving customer service for unemployment benefits, paid family leave, and disability insurance, for which the department received $136 million this year. So far, the department has begun designing a new online login that will work for unemployment benefits as well as paid family leave and disability insurance, and designing forms that are easier to read and understand.

If there’s a recession, some workers can’t turn to unemployment benefits. That includes the self-employed, who generally aren’t covered by unemployment benefits, said Jenna Gerry, a senior staff attorney at the National Employment Law Project. The federal government created temporary benefits for self-employed workers and contractors during the pandemic, but that ended in 2021.

Another large group that will find itself without unemployment benefits if a recession hits is undocumented workers – despite a major push from advocates and a bill passed by the Legislature. Under federal law, undocumented workers can’t get traditional unemployment benefits, said Gerry.

This year, worker and immigrant advocates pushed for a new pilot program that would have provided unemployment-like benefits to non-citizen workers – an idea Colorado lawmakers embraced this year. But California legislators didn’t provide funding for the program in the state budget, said Sasha Feldstein, economic justice policy director for the California Immigrant Policy Center. Curiously, they then passed a bill that laid out how the program would work, but which didn’t include funding, and Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed the bill, citing, in part, the absence of “a dedicated funding source.”

An $18 billion dollar problem

Another consequence of a recession could be growing California’s already massive unemployment debt.

The state’s unemployment insurance trust fund ran out of money during the pandemic, after so many laid-off Californians relied on the benefits. The federal government loaned California billions to keep benefits flowing, and the state still is on the hook to pay back about $18 billion.

California’s debt is uniquely large. While many states had to turn to the feds to pay out benefits during the pandemic, at this point just California, New York, Connecticut, Illinois and the Virgin Islands still have debt. California’s debt is roughly double the size of the other four combined.

“If there is a slowdown in the economy, we are totally and completely unprepared to be able to provide for California workers because of the deficit.”

Rob Lapsley, California Business Roundtable

This isn’t the first time the system has gone into debt. In the wake of the Great Recession, the debt grew to about $10 billion. California didn’t finish paying it off until the spring of 2018, according to H.D. Palmer, a spokesperson for the Finance Department, and the state spent about $1.4 billion on interest on the Great Recession era unemployment debt, according to Palmer.

Unemployment benefits are funded by employers, and in order to pay off the current debt, a federal tax on employers will automatically increase by $21 per employee in 2023, and ratchet up by an additional $21 per employee per year until the loan is repaid. This year state lawmakers also decided to kick in $250 million in state funds toward the loan principal and $342.4 million to cover the interest accrued so far.

But if the state goes into a recession, that debt could grow even larger.

“If there is a slowdown in the economy, we are totally and completely unprepared to be able to provide for California workers because of the deficit,” said Rob Lapsley, president of the California Business Roundtable, which represents major employers and has advocated for the state to contribute $10 billion to pay down the loan principal. “There may not be an interest in Congress to bail out California and New York,” Lapsley said.

But it would be unprecedented for the federal government to let a state’s unemployment system run out of money and stop providing benefits, said Gerry, with the National Employment Law Project. “That has never happened in the history of the unemployment insurance program since it was enacted in 1935.”

“I don’t think that there’s a real threat that no benefits will be available,” Gerry said. But having a system that repeatedly goes into debt means that taxpayers get stuck with an avoidable bill. And, Gerry said, “if we had more money in our trust fund, it would be easier to make the case that we could enhance benefits.”

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

STARK HOUSE SUNDAY SERIAL: The Broken Men Assemble in the First Chapter of Lionel White’s Clean Break

LoCO Staff / Sunday, Dec. 4, 2022 @ 7:05 a.m. / Sunday Serial

[Ed. note: Today your Lost Coast Outpost launches a new feature: STARK HOUSE SUNDAY SERIAL, a collaboration between the Outpost and Eureka-based Stark House Press (more about them at the bottom of this post) in which we aim to offer you, the LoCO faithful, a pulpy weekend escape.

Our first selection is Lionel White’s 1955 heist tale Clean Break, which would later be adapted by Stanley Kubrick as his 1956 film The Killing.

You may also note that Sunday Serial comes equipped with whimsical illustrations, a task the Outpost has delegated to some so-far friendly robots. Be nice to them now and maybe they’ll be nice to us in the future.

And now, on with the show…]

# # #

CLEAN BREAK

by

Lionel White

Summary: When Johnny gets out after four long, patient years, he is ready to pull the perfect heist. As he tells his girl, June, “That’s the beauty of this thing. I’m avoiding the one mistake most thieves make. They always tie up with other thieves. These men, the ones who are in on the deal with me—none of them are professional crooks. They all have jobs, they all live seemingly decent, normal lives. But they all have money problems and they all have larceny in them. No, you don’t have to worry. This thing is going to be foolproof.”

And it was, at least until Sherry enters the scene.

Chapter One

1

The aggressive determination on his long, bony face was in sharp contrast to the short, small-boned body which he used as a wedge to shoulder his way slowly through the hurrying crowd of stragglers rushing through the wide doors to the grandstand.

Marvin Unger was only vaguely aware of the emotionally pitched voice coming over the public address system. He was very alert to everything taking place around him, but he didn’t need to hear that voice to know what was happening. The sudden roar of the thousands out there in the hot, yellow, afternoon sunlight made it quite clear. They were off in the fourth race.

Unconsciously his right hand tightened around the thick packet of tickets he had buried in the side pocket of his linen jacket. The tension was purely automatic. Of the hundred thousand and more persons at the track that afternoon, he alone felt no thrill as the twelve thoroughbreds left the post for the big race of the day.

Turning into the abruptly deserted lobby of the clubhouse, his tight mouth relaxed in a wry smile. He would, in any case, cash a winning ticket. He had a ten dollar win bet on every horse in the race.

In the course of his thirty-seven years, Unger had been at a track less than half a dozen times. He was totally disinterested in horse racing; in fact, had never gambled at all. He had a neat, orderly mind, a very clear sense of logic and an inbred aversion to all “sporting events.” He considered gambling not only stupid, but strictly a losing proposition. Fifteen years as a court stenographer had given him frequent opportunity to see what usually happened when men place their faith in luck in opposition to definitely established mathematical odds.

He didn’t look up at the large electric tote board over the soft drink stand, the board which showed the final change in odds as the horses broke from the starting gate and raced down the long straight stretch in front of the clubhouse, on the first lap of the mile and a half classic.

Passing down the almost endless line of deserted pay-off windows, waiting like silent sentinels for the impatient queues of holders of the lucky tickets, Unger continued toward the open bar at the end of the clubhouse. He walked at a normal pace and kept his sharp, observant eyes straight ahead. He didn’t want to appear conspicuous. Although Clay had told him the Pinkerton men would be out in the stands during the running of each race, he took no chances. One could never tell.

When he reached the bar and saw the big heavy-set man with the shock of white hair, standing alone at one end, he shook his head almost imperceptively. He had expected him to be there; Clay had said he would. But still and all, he experienced an odd sense of surprise. It was strange, that after four years, Clay should have known.

The others, the three apron clad bartenders and the cashier who had left his box at the center of the long bar, stood in a small tight group at the end, near the opened doors leading out to the stands. They were straining to hear the words coming over the loud-speaker as the announcer followed the race.

There was a towel in the ham-like hand of the big man who stood alone and he was casually wiping up the bar and putting empty and half empty glasses in the stainless steel sink under it.

Unger stopped directly in front of him. He took the scratch sheet from his coat pocket and laid it on the damp counter, and then leaned on it with one elbow. The big man looked up at him, his wide, flat face carefully devoid of all expression.

“I would like a bottle of Heineken’s,” Unger said in his cool, precise voice.

“No Heineken’s.” The voice grated like a steel file, but also contained a gruff, good-natured undertone. “Can give you Miller’s or Bud.”

Unger nodded.

“Miller’s,” he said.

When the bottle and glass was placed in front of him, the bartender spoke, casually.

“Favorite broke bad—could be anybody’s race.”

“It could be,” Unger said.

The big man leaned forward so that his paunch leaned heavily against the thick wide mahogany separating them. He kept his voice low and spoke in a conversational tone.

“He’s in the ten win window, third one down, next to the six dollar combination.”

Unger, when he answered, spoke in a slightly louder tone than was necessary.

“It is a big crowd,” he said.

He drank half his beer and turned away.

This whole thing, this extreme caution on Clay’s part, was beginning to strike him as a little foolish. Clay was playing it much too cagey. The man must have some sort of definite anxiety complex. Well, he supposed that was natural enough. Four years in state’s prison would tend to make him a trifle neurotic.

The studiously hysterical voice of the announcer came alive in a high, intense pitch of excitement, but at once the context of his words was lost as the roar of the vast crowd swelled and penetrated the amphitheater of the all but deserted clubhouse.

Over and above the anonymous thunder of the onlookers, isolated, frenzied cries and sharp, wild islands of laughter reached the little man’s ears. Too, there was the usual undercurrent of groans and the reverberations of thousands of stamping feet. And then there was the din as a terrific cheer went up.

Unger made his way, unhurriedly, once more toward the wide doors leading to the stands.

With definite interest, but no sense of expectancy, his eyes went to the tote board in the center of the infield. Number eight had been posted as the winner. The red letters of the photo finish sign showed for second place. As the horses which had reached the neighborhood of the third pole slowed to a halt and turned back toward the finish line, Marvin Unger shrugged and turned to re-enter the clubhouse. He went at once to the men’s room, hurrying in ahead of the crowd.

Placing a dime in the slot, he entered a private toilet. He sat on the closed seat and took the handful of pasteboards from his pocket. Quickly he found the ticket on the number eight horse. He placed it on top of the others and then, removing his fountain pen from the breast pocket of his jacket, he carefully wrote on the margin of the ticket.

It took him not more than twenty seconds.

Getting to his feet, he tore the remaining tickets in two and scattered them on the floor. He then left the booth. He hadn’t waited, outside there in the grandstand, to see what price the number eight horse paid. He had used his own money to place his bets, and although he was ordinarily an extremely prudent man as far as financial matters were concerned, he really wasn’t interested. Irrespective of what the horse paid off, it must be considered a negligible sum.

After all, a few dollars could mean very little to a man who was thinking in terms of vastly larger amounts. A man who was thinking in the neighborhood of say a million to two million.

Moving toward the rapidly forming lines at the pay-off windows, Unger thought again of Clay. He wished that it was Clay himself who was doing this. But then, in all fairness, he had to admit that Clay had been right. It would have been far too risky for him to have appeared at the track. Fresh out of prison after doing that stretch and on probation even now, he would almost be sure to be recognized.

As a small cog in the metropolitan judicial system, Marvin Unger had a great deal of respect for the forces of law and order. He knew only too well the precautions Clay would have to take. His appearance, and recognition, at the track would be more than sufficient to put him back behind bars as a parole violator.

Unger once more reflected that Clay was unusually cautious. However, that element of caution in the man’s character was all for the best. Even this more or less cloak and dagger method of making the initial contacts might prove to be the safest plan. They couldn’t be too careful.

Regardless of the logic of his reasoning, he still resented being the instrument used. He would have preferred that the other man assume the risks.

He found a place behind a large, perspiring woman in a crumpled print dress, who fanned herself futilely with a half dozen yellow tickets, as the long line slowly moved toward the grilled window. It was the ten dollar pay-off window, the third one, and the one next to the six dollar combination.

The fat woman had made a mistake and she was told to take her tickets, which were two dollar tickets, to another window. She protested but the cashier, in a tired and bored voice, finally straightened her out. The annoyance of having to start all over at the end of another long line, however, failed to wipe the good-natured expression from her heavy face. She was still very happy that she had picked the winner.

Unger looked up at the face of the man behind the iron grillwork as he pushed his single win ticket across the counter. The ticket was faced down.

Without apparently observing him, the man’s hand reached for the ticket and he turned it over and looked at it for just a second. Expressionless, he tore off one corner and then carefully compared it with the master ticket under the rubber at his right. As he did so he memorized the writing which Unger had put on the ticket in the men’s room.

His face was still completely without expression as he read: “712 East 31st Street room 411 8 o’clock.”

A moment later he tossed the ticket into a wicker basket under the counter and his lean, agile fingers leafed through several bills.

“Fifty-eight twenty,” he said in a monotonous voice, shoving the money under the grill.

For the first time he looked up at Unger and he was unable to completely conceal the glint of curiosity in his faded, gray-blue eyes. But he gave no other sign.

Unger took the money and carefully put it in his trouser pocket before turning away from the window.

Clay is being overcautious, he thought, as he went out through the clubhouse and into the stands. It would have been safe enough for that bloated, red-faced Irishman back of the bar to have given the man the address. However, Clay had insisted that he knew what he was doing. He wanted to take no chances at all.

Marvin Unger remembered Clay’s words when he, Marvin, had protested that the whole thing had seemed far too complicated.

“You don’t know race tracks,” he had said. “Everybody is watched, the bartenders, the waiters, the cleanup men—everybody. Particularly the cashiers. It will be dangerous enough to have us all get together in town—we can’t take any chances of arousing suspicion by having Big Mike and Peatty seen talking together at the track.”

Well, at least it was arranged. Peatty had the address now and Big Mike also had it. It had been written on the edge of the scratch sheet which Unger had left on the bar when he had finished his beer.

Unconsciously he belched and the thin corners of his mouth tightened at once in annoyance. He didn’t like beer; in fact he very rarely drank at all.

Unger sat far back in the grandstands during the rest of the day’s card. He made no other bets. A quick mental calculation informed him that he was already out approximately sixty dollars or more as a result of his activities. It bothered him and he couldn’t help resenting the expenditure. It was a lot of money to throw away for a man who made slightly less than five thousand a year. It was a damned nuisance, he thought, that Clay lacked the money to finance the thing himself. On the other hand, he had to admit that had Clay possessed the necessary capital, he, Marvin Unger, would never have been taken in on the deal.

He shrugged it off and stopped thinking about it. What, indeed, would a few hundred or a couple of thousand mean in comparison to the vast sum of money which was involved? His final thought on the subject was that he was lucky in at least one respect—he might have to put up the expenses but at least he wouldn’t have to be in on the violence. He wouldn’t have to face the gunfire which would almost be sure to take place when the plan was ultimately consummated.

His naturally aggressive personality, the normal complement of small stature and the inferiority complex he suffered as the result of an avocation which he considered far beneath his natural intellectual abilities, didn’t encompass the characteristic of unusual physical courage. His aggressiveness was largely a matter of a deep-seated distaste for his fellow man and a sneering condescension toward their activities and pastimes.

Waiting stolidly until the end of the last race, Marvin Unger joined the thousands rushing pell-mell from the track to crowd into the special trains which carried the winners and losers alike back from Long Island to Manhattan.

He reached his furnished rooms on Thirty-first Street, on the fourth floor of the small apartment house, shortly after seven o’clock, having stopped off first for dinner.

# # #

2

Michael Aloysious Henty was exceptionally busy for the first twenty minutes after the finish of the last race. The usual winners stood five and six deep, calling for Scotch and rye and Bourbon and anxious to get in a last drink or two before joining the lines in front of the pay-off windows. The excitement of having won was still in them and the talk was loud and boisterous. A few of the last minute customers, however, leaned against the bar and morosely tore their losing tickets into tiny fragments before scattering them to the floor where they joined the tens of thousands of other discarded pasteboards which had been disgustedly thrown away by those without the foresight to select the winning horse.

Big Mike always hated this last half hour of his job. There was far too much work for the four of them and then there was always the argument with the half dozen or so customers who wished to linger on past closing time. Even after the final drink had been served, there was the bar to he cleaned up, the glasses to be washed and the endless chores of getting the place in order. Invariably the bartenders missed the last special train of the day and would have to wait an extra twenty or twenty-five minutes to get a regularly scheduled train back to New York.

Mike was always in a hurry to get on that train. He was an inveterate gambler and in spite of endless years of consistently losing more than half of his weekly pay check on the horses, he still had a great deal of difficulty knowing just where he stood at the close of the last race. He had no mind for figures at all.

Of course, as an employee of the track—or at least of the concessionaire who had the bar franchise at the track—he wasn’t allowed to make bets at the regular windows. Instead, each night he would dope the following day’s events and then in the morning, on his way to work, he’d drop off at the bookie’s and place his bets. A solid, dependable man in spite of his weakness for the horses, he was given credit by his bookmaker and usually settled up at the end of the week when he received his salary check.

It was during the long train ride home that he would take out his scratch sheet and start figuring out how he had made out on the day. On this particular day, he was more than normally anxious to begin figuring. Because of what happened—of Clay getting in touch with him and the excitement and everything—he had been a little too optimistic and bet a good deal heavier than usual.

He knew that he had lost on the day, but he wasn’t quite sure how much. Not only had he a poor mind for figures, but he couldn’t remember pay-off prices from one minute to the next. He was only sure of one thing; he had bet a total of well over two hundred dollars on the afternoon’s races and only one of his horses had come in.

There was a deep frown on his smooth forehead as he thought about it. And then, oddly enough, the same fragment of a thought passed through his mind which had passed through that of Marvin Unger.

What the hell was a few dollars, after all, in comparison to the hundreds of thousands which had preoccupied his mind these last few days?

Big Mike was suddenly aware of a commotion at the end of the bar and he looked down to see a tall slender girl who couldn’t have been more than nineteen or twenty, laughing hysterically. The girl screamed something to her companion, a fat, middle-aged man with a bald perspiring head, and then, with a snake-like movement, she lifted the tall glass in her hand and dumped the contents down the front of the man’s gaily flowered sport shirt.

Two of the other boys were already straightening things out and a private track policeman was rapidly moving toward the group, so Mike turned back to the work in front of him.

There was a look of stern reproach on his wide, flat face. Big Mike was a moral and straight-laced man, in spite of a weakness for playing the horses and an even greater weakness for over excess in eating. Sixty years old, a good Catholic and the father of a teen-aged daughter, he highly disapproved of the younger generation. Particularly that segment of it he saw each day lined up at the bar in front of himself.

Automatically he picked up a handful of used glasses from the bar and went back to thinking of money. Once more he thought of that vast sum—a million, perhaps even two million dollars. And then, from the money, his mind went to Johnny Clay.

Johnny Clay was a good boy. In spite of the four years in prison, in spite of his criminal record and everything else, Johnny was still a good boy. Mike’s vanity had been very pleased when Johnny had remembered him from the old days and had looked him up, once he was out of prison and back in circulation.

Big Mike had known Johnny from the time he was a tow headed kid on the Avenue, when Mike himself was behind the stick at Costello’s old bar and grill. Even in those days, when he had been still in knee pants, Johnny had been wild. But his heart had always been in the right place. He’d been smart, too. A natural-born leader.

Mike remembered him later, when he’d begun to hang around the bar and play the juke box. He’d never been a fresh kid and he drank very little. He’d never given Mike any trouble at all.

Of course Big Mike hadn’t approved of the way Johnny got by. There was no doubt but what he’d been on the wrong side of the law. And Mike had been pretty upset when the cops had finally picked up young Johnny and put him away on that robbery rap.

It was only in recent years that Mike had become a little more liberal in his thinking. The endless poverty of his life and his constant struggle to get along on a bartender’s salary—a salary which he invariably shared with a series of bookmakers—had embittered and soured him. When he thought of all that money which went through the grilled windows of the track every day, he began to wonder if there would be really anything wrong in diverting some of it in his own direction.

He had thought about it often enough, God knows. But it was only when Johnny got out and had approached him with the idea that the thought was anything but an idle daydream. Well, if anything could be done about it, he reflected, Johnny was certainly the boy to do it. That night he’d know a lot more about the whole thing. He tried then to remember the address which had been written on the side of the scratch sheet the man had left at the bar. He couldn’t remember it, but the fact didn’t worry him. He had the sheet in his coat pocket.

He did remember that the time had been set for eight o’clock. He’d have to hurry through his dinner to make it. Mary would be annoyed that he was going out for the evening. He had promised her he would talk with Patti.

A worried frown crossed his heavy face as he thought of the girl. Lord, it seemed like only yesterday that she was a long-legged baby in bobby socks, her flaming red hair done up in two stringy braids.

Patti was a good girl, in spite of what her mother, Mary, said. It was the neighborhood, that was the trouble.

Money, money to get away from the Avenue and out into the country some place. That’s all that was needed.

Mike would like to move himself. He hated that long train ride from New York to the race track and back each day. Yes, a small, modest little house with a garden, somewhere out past Jamaica—that would be the ticket. It began to look as though the old dream might really come true.

By the time the Long Island train was roaring through the tunnels under the East River, Mike had figured out that he’d lost a hundred and twenty-two dollars on the day. His furrowed forehead was pale and beads of sweat stood out on it. A hundred and twenty-two dollars—Jesus, it was a lot of money. Almost half what he had promised to get together for Patti so that she could take that stenographic course at the business college.

Big Mike got to his feet while the train ground to a stop at Penn Station.

What the hell, he thought, another month and he could be giving that kind of money away for tips. He was one of the first ones out of the car; he was in a hurry. He had a lot to do before eight o’clock that night and he didn’t want to be late.

# # #

3

George Peatty caught the same train which had taken Big Mike back to Manhattan. He had even seen Mike, ahead of him in the small crowd at the station, but he had made no effort to reach the bartender’s side. He had known the other man for a number of years, but they were only acquaintances—not friends. This, in spite of the fact that Mike had been responsible in a way for getting him his job at the track.

It wasn’t that they didn’t like each other; it was merely that they had nothing in common. Nothing that is except George’s mother, who had been a girlhood friend of Mary McManus, who later became Mary Henty, Mike’s wife. But George’s mother was dead and it had been all of ten years since she had induced her friend Mary to intercede with Big Mike in order to get her son an introduction to one of the track officials.

George had, of course, been duly grateful. But it had ended there. George had always felt a sense of embarrassment with the older man. Big Mike had known a little too much about him; had known about the early days when George was pretty wild. He had had a bad reputation for getting into scraps.

But that had all been a long time ago; long before he’d met Sherry and fallen in love with her.

Watching Big Mike enter the train, George turned and walked down the side of the car until he came to a second car. He climbed aboard and found a seat well to the rear.

At thirty-eight, George Peatty was a gaunt, nervous man, who looked his age. His brown eyes beneath the receding line of thin, mouse-colored hair, had a tendency to bulge. His nose was large and aquiline and he had a narrow upper lip which unfortunately failed to conceal his crooked, squirrel like teeth. His chin was pointed and fell in an almost straight line to his overlarge Adam’s apple.

He had the long fingered hands of a pianist and kept them scrupulously clean. His clothes were conservative both as to line and price.

The moment he was seated, he unfolded the evening paper which he had picked up at the station newsstand. He started to read the headlines and his eyes remained on the page, but in a second his mind was far away. His mind was on Sherry.

After two years of marriage he still spent most of his idle time thinking of his wife. He was probably, now, more obsessed than he had ever been, even in the very beginning.

George Peatty’s feeling toward his wife had never changed since the day when he had first met her, some year and a half before they were married. He loved her, and was in love with her, but even beyond that, he was still wildly infatuated with her. Marriage had served only to intensify the depth of his passion. He had never recovered from his utter sense of bewilderment when she had finally agreed to share his bed and his life. He still believed that he was the luckiest guy in the world; notwithstanding the fact that he fully realized that he was far from being happy. Luck and happiness were, for him, two completely different things, although he recognized that in his case they were the reverse sides of the same coin.

Thinking of Sherry, he began, as he always did on the train ride back to his apartment on the upper West side, a silent prayer that Sherry would be there when he got home. As a man who had spent years unconsciously figuring odds, he knew automatically that the chances were about one in ten that she would be.

The heavy vein in the right side of his neck began to throb and there was a nervous tick at the corner of his eye as he thought about it. As crazy as George Peatty was about his wife, he was not completely blinded to her character or to her habits. He knew that she was bored and discontented. He knew that he himself, somehow along the way, had failed as a husband and failed as a man.

In the hard core of his mind, he blamed the thing not on himself and certainly not on Sherry. He blamed it on luck and on fate. A fate which limited his earning capacity to what he could make as a cashier at the track. A fate which had made Sherry the sort of woman she was—a woman who wanted everything and everything the best.

Not, George thought, that she didn’t deserve everything. Anyone as lovely as Sherry should be automatically entitled to the best that there was.

Dropping the newspaper in his lap, he closed his eyes and leaned his head back. He was suddenly relaxed. It wouldn’t be long. No, it wouldn’t be long before he would be able to give her the things which she wanted and deserved.

His lips moved slightly, but wordlessly, as he said the words in his mind.

“Thank God for Johnny.”

At the moment he was only sorry about one thing. He would have liked to have told Sherry about the meeting he was going to at eight o’clock that night. He would have liked to have told her about the entire thing. Even now he could see her smoldering eyes light up as he would outline it to her. But then, almost at once, he again began to worry about whether or not she’d be home.

Getting off at the station in New York, he stopped at a florist shop in the Pennsylvania arcade and bought a half dozen pink roses before getting into the subway and taking the express up to a Hundred and Tenth Street.

# # #

4

Looking down at the shock proof silver watch on his large wrist, Officer Kennan noticed that it was twenty-two minutes before six. Carelessly he swung the wheel of the green and white patrol car and turned into Eighth Avenue. He would just have time to drop by Ed’s for a minute before taking the car into the precinct garage and checking out for the day.

Time for two quick ones and a word or two with Ed and then he’d be through for twenty-four hours. God, with the traffic the way it was in New York these days, he could sure use the rest. It was murder. He was not only thirsty but he was thirsty for a couple of good stiff shots. Thinking about Ed’s he began to worry about the chances of running into Leo. Christ but he hoped that Leo wouldn’t be around. He was into him now for well over twenty-six hundred dollars and he hadn’t made a payment in more than three weeks.

Not that Leo really worried him; he would be quick enough to tell the little bastard where to get off. The only thing was that Leo had connections. Important connections with some of the big brass in the department. That was one reason Leo had not hesitated to loan him money when he needed it. It was the reason Leo confined the bigger part of his loan shark business to cops and firemen. He had political pull.

For a moment Randy Kennan, patrolman first class, considered the possibility of passing up Ed’s. But once more he shrugged. He wanted those two drinks and Ed’s was about the only place he knew where he could walk in and get them without trouble and without embarrassment. Also, without money.

He drove to Forty-eighth Street and turned east and went a half a block and then pulled over to the right hand side of the street. There was a mounted patrolman leaning over the neck of his horse, talking to a cab driver, not far from the corner. The street was crowded with traffic and hurrying pedestrians, but Officer Kennan didn’t bother to pay them much attention.

He left the keys in the car and pulled up the brake as he opened the door. A moment later he walked several hundred feet down the street and turned into a bar and grill.

There were a couple of dozen customers lining the bar but Randy Kennan walked directly through to the back room. Ed saw him as he passed opposite the cash register and looked up with a nod and a friendly smile. Randy winked at him.

He liked Ed and Ed liked him. It wasn’t like shaking a bartender down for a couple of fast shots. They were friends. Had been friends now for a good many years. In fact from the time they were kids together over at St. Christopher’s.

He was about to push through the swinging doors into the kitchen when he heard his name called. He didn’t have to look.

It was Leo and Leo was sitting where he usually sat, in the very last booth at the left. He was alone.

Randy hesitated a second and looked over at him. Then he sort of half nodded his head toward the kitchen door. He didn’t want to go to the booth, even if Leo was alone. It would be bad enough if some passing lieutenant or captain wandered in, finding him there at all. It would never do to be found sitting in a booth in uniform.

There were two Italian chefs and a dishwasher in the kitchen but Randy gave them not the slightest attention. He walked over to a counter and picked up a slice of cheese from a plate. He was munching it a minute later when the swinging doors opened and Ed came in. He carried a bottle of rye in one hand and a glass in the other.

“Hot day, kid,” he said as he sat them on the table next to Randy. “I see your pal Leo outside. He wants to talk to you.” Randy smiled at his friend, sourly.

“Tell the sonofabitch to come in here and talk,” he said. “He knows damn well I can’t…”

“I’ll tell him, Randy,” Ed said.

“How about joining me in one,” Kennan said, looking up from the drink he was already pouring.

“Hell boy,” Ed said, “I’m just coming on. You’re going off, aren’t you?”

Randy nodded.

“Yeah.”

Ed left a half minute later to get back to the rush of customers. Leo passed him in the doorway.

Everything about Leo Steiner was bland. His soft brown eyes were almost childlike in their innocence; the large, unwrinkled face was heavy with good nature and friendliness. He always spoke as though he were half laughing. Leo wore a nylon sports shirt with the top button fastened and no tie. He affected sports jackets and flannel trousers. There wasn’t a thing about him which wasn’t completely deceptive.

“Randy boy,” he said. “How’s tricks?”

Officer Kennan nodded in a noncommittal way. He indicated the bottle of whiskey with a nod of his head.

“Drink?” he asked.

“You know I never touch the stuff,” Leo said and laughed as though it were a joke. “My nerves. It gets my nerves.”

Randy smiled wryly. Nerves? Hell, Leo Steiner had about as many nerves as a hippopotamus.

Leo leaned back against the table so that he half faced the other man.

“You know, kid,” he said, “I’m in a little trouble. Maybe you can help me out.”

Randy nodded again. Here it comes, he thought.

“Yeah,” Leo said, looking anything but like a man in trouble. “It’s money. Gotta raise some quick dough. What do you…”

“Look, Leo,” Randy said. “You don’t have to beat about the bush. I know I’m late and I know just what I owe you. But I gotta have a little more time. Things have been breaking bad lately. I need time.”

“Boy,” Leo said, “I know just how it is. I sure want to give you all the time in the world. But the trouble is, I just can’t do it. I need to get up some cash and right away. Guess I’ll have to get say around five notes from you this week.”

Randy reached for a second drink and swallowed it hurriedly. He turned to the other man and spoke quickly.

“Leo,” he said, “I can’t do it. I just can’t make it this week!”

“You get paid this week,” Leo said.

“Yeah, I get paid. But I’m in hock to the pension fund for a loan and when they take out theirs, I got just about nothing left at all. I gotta have a little more time.”

Leo shook his head, sadly.

“How much time, Randy?”

Randy looked directly at the other man and spoke slowly.

“Listen,” he said. “I got something good coming up. Real good. But it takes time.”

“What is it,” Leo asked. “Not another horse, Randy?”

Kennan shook his head.

“No—not a horse. This is a sort of private deal. All I can tell you is, just give me say another thirty days, and I think I can take care of everything.”

Leo nodded slowly.

“It’s twenty-six hundred bucks now, Randy,” he said. “All right, suppose we say another thirty days—let’s say I can do that. And we’ll call it an even three grand—thirty days from now.”

Randy Kennan’s eyes narrowed and there was a mean line around the corners of his mouth.

“Three grand—Jesus Christ! What kind of goddamned interest is that to ask a man.”

“It’s your idea, Randy,” Leo said, his voice soft and almost sympathetic. “You want the thirty days—not me. I just want my money. In fact, Randy, I gotta go out now, on account you’re not paying me anything, and borrow the dough. I gotta probably borrow it from my friend the Inspector—and you know how tight he is.”

Kennan caught the full significance of the threat. He would have liked to grab the fat man by his lapels and slap him until he was silly. But he didn’t dare. He knew what Leo could do; he knew Leo’s connections.

“O.K.” he said. “O.K. Shylock. Three grand in thirty days.”

Leo reached over and patted the big man on the shoulder.

“Good boy,” he said. “I know I can count on you, pal.”

He turned and went back into the barroom.

Randy Kennan took a third drink. His hand was shaking and he gritted his teeth in anger as he poured from the bottle.

“The bastard! The fat bastard,” he said under his breath.

Well, in thirty days he’d pay him. He’d pay the sonofabitch his three grand.

He began to dream of the future. He’d stay on the force for another six months, he figured, once it was all over and done with. Yeah, that would be the safest bet. But then, when things quieted down, he’d get out and get out fast. Someday, someday in the next few years he’d catch up with Leo. He smiled grimly when he thought of what he’d do to Leo Steiner.

He sat his glass down and looked again at his wrist watch. It was getting on and he’d have to hurry. He still had to turn in the patrol car, sign out and get showered and dressed in his street clothes. He wanted to find time to get something to eat, too, before he showed up for the eight o’clock appointment.

He was looking happier as he left Ed’s place. He was thinking of that appointment.

It was luck, real luck. Running into Johnny like that, the very day he’d been sprung upstate, was the best thing that had ever happened to him. Yeah, that was the break he’d been waiting for for a long, long time now.

# # #

Tune in next week for the next chapter of Clean Break!

Stark House Sunday Serial is brought to you by the Lost Coast Outpost and Stark House Press.

Based in Eureka, California since 1999, Stark House Press brings you reprints of some of the best in fantasy, supernatural fiction, mystery and suspense in attractive trade paperback editions. Most have new introductions, complete bibliographies and two or more books in one volume!

More info at StarkHousePress.com.

GROWING OLD UNGRACEFULLY: RIP, Christine McVie

Barry Evans / Sunday, Dec. 4, 2022 @ 7 a.m. / Growing Old Ungracefully

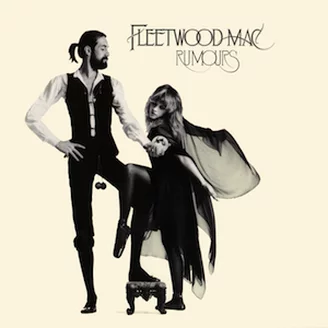

It’s only 25 miles between the turnoff at Leggett and Westport-Union Landing State Beach, but that stretch of Highway 1 — twisting and turning up, down and around — takes about 40 minutes in our old VW camper. We know of accidents, and fantasize about head-on collisions every time we drive it, usually twice a year; we love the paddling and hiking opportunities on the Mendocino coast, and have good friends down there whom we regularly visit. To help me focus on driving that tricky stretch of road, we’ve made it a tradition over the years to play Rumours, Fleetwood Mac’s megahit album from 1977.