The other barbers were sitting on the sofa watching the news. Beside them, an old man with a deep, raspy voice was reading a newspaper and haranguing the others. He was going on about Gulen.

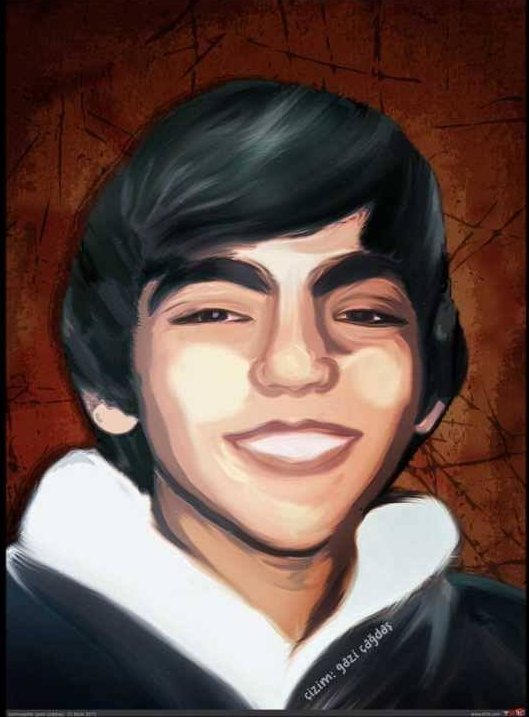

On the TV they were showing the live coverage of Berkin Elvan’s funeral. He was the 15 year-old boy whose skull was crushed by a tear gas canister shot fired by police while on his way to buy bread during anti-government protests last year. The boy spent nearly a year in a coma, slowly wasting away, and weighed only about 35 pounds when he finally died last Monday.

There were big rallies, in Istanbul, Ankara and around the country that night, the crowds expressing both their grief over young Berkin and their anger at Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his ruling AK Party. More protests were already gathering in the wake of the funeral.

“Many people will be out tonight,” I said to my barber, who had finished cutting and was getting ready to rinse my hair.

“Evet,” the barber said, nodding and getting a towel. “Many people, in Taksim, Ankara …”

“And here, outside at the Bull Statue,” I said.

“Evet. At the Bull too.”

The old man had left by the time I was ready to pay, and the TV was switched to the football scores. Outside it was sunny, but a stiff wind blew in the still naked trees. It had been a mild winter, but the past few days were rainy and cold, as if the winter were attempting one final, futile attempt to gain a foothold.

On Bahariye Street, students carrying signs that read “BERKİN ELVAN” sat outside a lycee, and more were gathered at the Bull Statue, a score of them, and they were chanting the boy’s name, while the busy late morning traffic went by. It was a modest prelude for events to come later. Meanwhile, above the students, the red and blue streamers of the opposition party blew in the wind like confetti, a reminder of the upcoming local elections only two weeks away.

I thought of my early morning lesson with a businessman in Erenkoy. He was a Black Sea Turk and a prominent builder, with contracts stretching from Istanbul to Iraq and even potentially in Africa.

“The elections will be important,” said the businessman. “For if Tayyip’s party get 40 percent or more there will be many arrests, thousands even. They are already planning this. There will be arrestss inn the police, the courts, of all of Gulen’s people. But if he doesn’t get 40 percent, then it could be interesting. There could be early Parliamentary elections.”

The atmosphere in the country on that morning was tense, uncertain, almost like a country on the verge of a nervous breakdown. For there are intersecting currents that wash around the now-interred body of the unfortunate Berkin Elvan. He was killed unintentionally during anti-government protests, protests aimed at taking down what is seen by many as an increasingly authoritarian administration. At the same time, Erdogan’s AK Party has been rocked by a corruption scandal, a scandal that saw three parliament deputies sons arrested on charges of bribery.

The corruption scandal itself stemmed from a split between Erdogan and an old ally, the retired religious cleric Fethullah Gulen, who lives in Pennsylvania, USA. Erdogan has accused Gulen and his supporters, known here as the Hizmet movement, of trying to run a parallel state. The rift between the two erupted when Erdogan called for shutting down religious schools in Turkey (many of which are operated by Gulen followers). Gulen allegedly fired back by exposing corruption in the Erdogan administration, even leaking supposed telephone calls by the prime minister and uploading them onto the Internet, where they have added fuel to the fire for the anti-government protesters.

All of these conflicting forces surround the grave of the young boy, Berkin Elvan, and give a strange resonance to the voices of the student protesters already out on the streets this sunny, windy morning. Perhaps they see in the boy something of themselves, their own murdered innocence, or else their own fears and uncertainties about the future of their country.

****

Later that day, and well into the evening, thousands of people gathered in Oykmeydani, the neighborhood where Berkin had lived. It’s a diverse neighborhood, with mostly low-income and working class Alevis living near conservative Black Sea Turks. Just hours after the funeral, as the people continued to protest in the streets , a shot, or shots, rang out and a second youth, 22-year-old Burak Can Karamanoglu was killed. The circumstances of the death remain unclear.

“Such an incident does not take place in the neighborhood where we live. Everything happened 200 meters further away. A group of people were marching together over there as the street lights were off,” the murdered young man’s father Halil Karamanoğlu was quoted as saying by The Hurriyet Daily News. He said his son had joined his friends to watch the protesters.

“They were hanging outside arm-in-arm as three friends. They were watching [people] from the side of the road. Then they were attacked. Everything happened in five minutes. The time between the boy coming home [from work], leaving again and the incident occurring was 10 minutes. They were shot by a stray bullet within 10 minutes. The bullet came from protesters,” Karamanoğlu said.

So the next day the funeral was held – the second funeral in two days. The cruel irony of the second death lingers, as do the many questions about what will come of all of this unrest, political gamesmanship and tragedy. Some, like my girlfriend Ozge, have had enough.

“I’m just tired of it all,” she said, one evening as we watched the news. “It’s the same problems over and over again in this country. Why do we have to have these problems?”

Meanwhile, all around the city, you can see the name BERKİN spray-painted on sidewalks and buildings, meaning that the boy’s death – and the circumstances that brought it about – will not be soon forgotten.

James Tressler was a reporter for The Times-Standard. His latest book, “Letters from Istanbul, Volume 1” is available at Lulu.com. He lives in Istanbul.

CLICK TO MANAGE