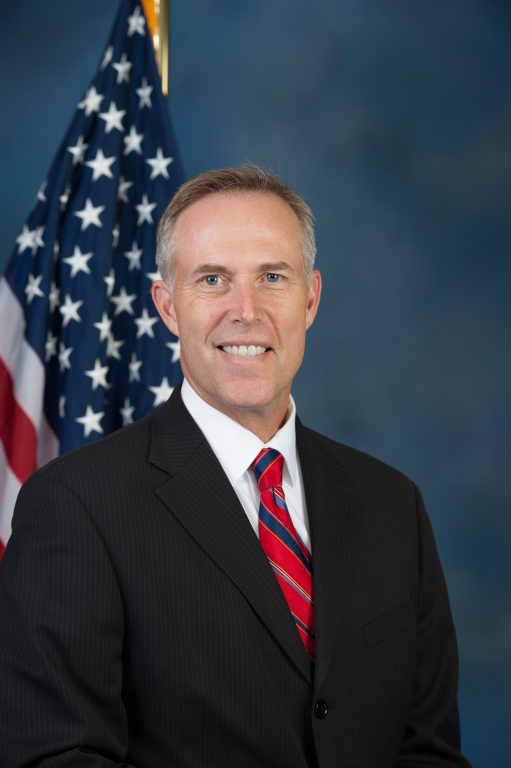

Yesterday, our representative to the U.S. Congress, Jared Huffman, issued a cautionary rejoinder to President Barack Obama’s Sept. 10 ISIL speech, questioning both the methods and the motives of a mission that amounts to another war in the Middle East.

Yesterday, our representative to the U.S. Congress, Jared Huffman, issued a cautionary rejoinder to President Barack Obama’s Sept. 10 ISIL speech, questioning both the methods and the motives of a mission that amounts to another war in the Middle East.

Huffman writes that that while he shares Obama’s “desire to destroy” the militant group known, among other acronyms, as ISIL, he doesn’t believe the president should take advantage of the “very broad authorizations” granted to the Commander in Chief after 9/11. “What happens if the next president wants to escalate and broaden the war without congressional approval?” he writes.

He goes on to call for a “broad international coalition” of allies before going to war as well as “a clearly defined objective, a realistic timeline in which to achieve it and an honest discussion of how to pay for it.”

Here’s the statement in its entirety:

On the 13th anniversary of 9/11, our nation once again honored lives lost, gave thanks to our brave first responders and reflected on lessons learned from that terrible day. I’m proud of the unity and resolve our country demonstrated in response to 9/11 and grateful that we are better prepared to prevent terrorist attacks.

I’m also mindful of mistakes we made in seeking to address security threats in the wake of 9/11 — most notably, the disastrous Iraq war which cost us dearly in blood and treasure and did not make us safer. Today, the world is more turbulent and dangerous than at any time since the Cold War. Protecting our national interests and keeping Americans safe requires that we be smart, not just tough. We must learn from past mistakes.

I listened carefully Wednesday night as President Barack Obama outlined his strategy for confronting ISIL. I agree with the president that ISIL is a brutal terrorist group that poses a threat to the Middle East and aspires to be more than a regional menace. I share his desire to destroy this group.

However, I believe the strategy outlined by the president — bombing in Iraq and Syria, supporting Kurdish and Iraqi partners on the ground, and recruiting, vetting and arming moderate Syrian rebels — falls short in several key respects.

First, we must restore the constitutional safeguard of wars being authorized by Congress. President Obama should obtain congressional authorization — not just to recruit and train Syrian fighters but for the entirety of what has been described as an intense, multi-year military intervention: a war. Because prior congresses in the wake of 9/11 granted very broad authorizations to use military force, the president may not technically need a new one. He should seek one anyway. It’s what our constitution specifies for going to war, and it’s the right thing to do.

Without a specific authorization we cannot have confidence in assurances such as “no boots on the ground.” We already have more than 1,500 troops in Iraq. We are told they won’t engage in combat roles, but what does that mean? What happens if an American pilot has to eject over ISIL territory, an American adviser is captured or Russia sends more troops and weapons to Assad? What happens if the next president wants to escalate and broaden the war without congressional approval?

I also question some of the strategic assumptions. While I have great faith in our troops, it seems unlikely that the United States can essentially create a “moderate” partner in Syria that can do everything the strategy assumes, including defeating ISIL in Syria while battling Assad to bring about a political solution and then emerging as a moderate governing group in post-war Syria

I’m concerned that reliance on the Free Syrian Army may become a modern-day Bay of Pigs and that our guns, armored vehicles and missiles may once again fall into the hands of extremist groups who turn them against us and our allies.

In Iraq, the strategy assumes a political reconciliation and alliance between Sunnis and the Shiite majority against ISIL. I’m encouraged that former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki is gone, but the new Iraqi government’s promise to be more fair and inclusive of the Sunni minority is untested and Iran still wields a destabilizing influence.

We should be honest and realistic about the fact that non-Kurdish parts of Iraq may not provide a stable and reliable “partner on the ground.”

Further, America should know better than to commit to a new Middle East war before marshaling a broad international coalition. The countries most affected by the ISIL threat — including Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Turkey — must play meaningful, visible roles lest this be perceived as the Christian West fighting the self-proclaimed Islamic State, which would fuel ISIL recruiting. Our European NATO allies, all of whom are affected by the ISIL threat, should also carry their share of the risks and burdens.

Finally, before committing American lives and resources to this war, we must have a clearly defined objective, a realistic timeline in which to achieve it and an honest discussion of how to pay for it. Prior generations knew they had to pay for wars — so they stepped up, raised taxes and sold war bonds. Our generation has allowed wars to be financed by deficit spending which contributes to a national debt that is driving cuts in education, research, infrastructure and social services. Any congressional authorization for war should include the revenue to pay for it. We must stop pretending wars are free.

This week, Congress has an opportunity to debate this critical issue, to reassert its Constitutional authority on the subject of war and to ensure that our response to ISIL is smart and effective. Deciding to go to war is Congress’ most solemn responsibility. It should never be taken lightly and certainly never abdicated.

CLICK TO MANAGE