We already have immortality, but we have it in the wrong place. We have it in the germ plasm; we want it in the soma, in the body.

— George Wald

We are, to a first degree of approximation, immortal. The genes in nearly every cell of our bodies, inherited from our parents and bequeathed to our children, have such a long and unbroken history that to call them mortal would be churlish. Three-and-a-half billion years — a quarter the age of the universe! — that’s how old we really are. Not, perhaps, the “we” we admire, cherish, and defend — what feels like our “essential selves” in which our hopes and dreams and memories reside—but the part of us hidden from awareness, our genome, what biologist George Wald calls our “germ plasm.”

Philosophers have explored the notion of eternal life for—well, not three billion years, but as long as there have been philosophers. And when archaeologists unearth ancient graves replete with the necessities for making the transition from this life to the next, it’s clear that our forebears had life-after-death on their minds. In Egypt, they’ve unearthed food and drink in 5,000-year-old graves; in China, an army of clay warriors accompanied the state’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, to his next life; and in Mexico, K’inich Janaab’ Pakal, the greatest lord of Palenque, was interred in a stone sarcophagus with a carved map on its lid to help him navigate between the two worlds.

Temple of Inscriptions (on left), Palenque, in which the Mayan king Pakal was interred in 683 AD after reigning for 68 years. (Barry Evans)

The immortality imagined by these ancients — and by some three-quarters of Americans today — is, of course, based on wishful thinking, in the absence of actual evidence. But this isn’t the kind of immortality that interests biologists who, taking a scientific worldview, thrill to the ancestry of the genome. Whether or not you know and appreciate the fact, every cell of your body (other than red blood cells) encodes its history from the very earliest life here through countless reproductions (first by mitosis, then sexually). And here you are today, a walking, talking Record of Life on Earth.

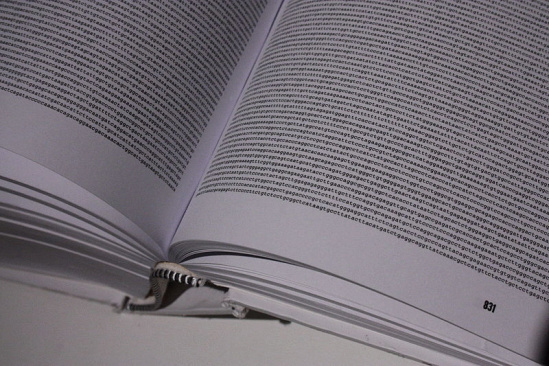

The human genome has been likened to a 23-chapter book, in which an individual letter stands for one of the nucleotide bases of DNA. In this analogy, chapters correspond to chromosomes, with each chapter containing around 200 million letters (A, C, G and T). The book, then, contains nearly five billion letters in total. (For comparison, the Bible has about three and a half million letters.) A complete copy of the “book of you” — your genome — can be found (with a microscope!) in the nucleus of virtually every cell in your body. That’s the near-immortal “you” — copied almost-but-not-quite flawlessly from generation to generation to generation.

The human genome can be thought of as a huge book with page after page of the letters A, C, G, T in fine print. (Stephencdickson/Creative Commons)

It may not be exactly what you hoped for when contemplating your long-term future (no harps, grapes, celestial choirs, virgins — but no eternal torment, either), and you have to share your good fortune democratically with every rattlesnake, mosquito and thistle on the planet. But immortality is yours. To squander or to celebrate? Choose wisely!

###

Barry Evans gave the best years of his life to civil engineering, and what thanks did he get? In his dotage, he travels, kayaks, meditates and writes for the Journal and the Humboldt Historian. He sucks at 8 Ball. Buy his Field Notes anthologies at any local bookstore. Please.

CLICK TO MANAGE