“So you don’t want to go to open mic tonight?”

“No.”

“No you don’t want to go, or no you do want to go?”

“Yes.”

###

Time was, French was the international language of diplomacy and business because, it’s said, French lacks the ambiguity of English. English, ambiguous? Er, yes. Happens everyday.

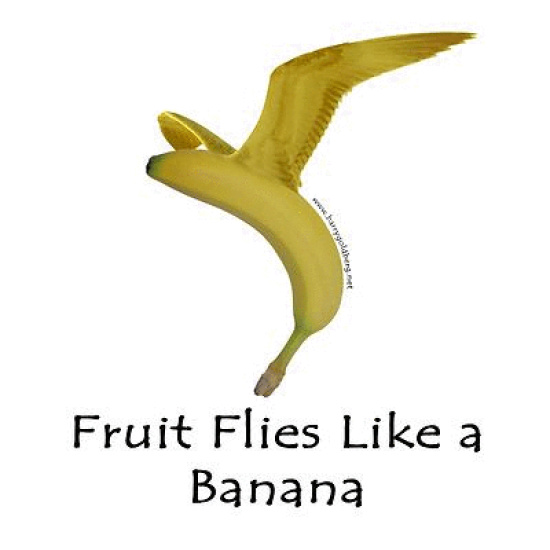

“Time flies like an arrow.”

This old chestnut offers an insight into how a simple sentence in English can be interpreted in at least five ways:

- If you know how to measure the speed of an arrow, you can time flies in the same way. (Imperative)

- Imagine how a sentient arrow would time flies, and follow its example. (As in, say, “Eat ants like an anteater.”) (Imperative)

- Measure how fast arrow-shaped flies travel. (Imperative)

- “Time” whizzes by just as an arrow does. (Declarative) (The usual understanding of the phrase.)

- Not just any old flies (not even fruit flies) but the sub-species “time flies” really enjoy an arrow.

12:00 a.m. or p.m.?

The sign on the counter of a local sports equipment store read, “Kayak classes Fridays 9-12 p.m.” “Isn’t that rather late for a class?” I asked. After doing a double take, the clerk assured me that the class ran for three hours in the morning, ending at noon. “But 11:59 p.m. is a minute before midnight, so wouldn’t 12:00 p.m. be midnight?” I persisted. We agreed to differ, victims of the trap that claims countless travelers every year (which is why you’ll often see flights leaving at 11:59 a.m. or 11:59 p.m., to avoid the ambiguity).

The daylight savings snare

Consider what might have happened to a plane scheduled for a 1:30 a.m. departure on Sunday November 1 (in the middle of putting the clocks back an hour). Did it leave at 1:30 a.m. PDT—or one hour later, at 1:30 a.m. PST? Who knows? Who cares? Well, everyone involved in scheduling: flight planners, air traffic controllers, passengers and crew.

Meanwhile if the flight was to the UK (nominally 8 hours ahead of Pacific Time), can we figure out when it will arrive in London? Only if we remember that “limey summertime” ended a week earlier, on October 25.

Oh, and don’t forget, if you were in Hawaii, most of Arizona and a small part of Alaska, you wouldn’t have had to do a thing—no daylight savings there. (Trivia: Indiana had three time zones until 2006.)

(This isn’t small potatoes. If we all take 10 minutes changing our clocks and watches twice a year, at the current average hourly wage of $22.45, that’s collectively costing us nearly two billion dollars annually.)

“This” and “next”

Let’s say you’re reading this on Sunday, November 15, and I refer to an event coming up next Friday. You’re hooked, and turn up on Thursday 26 — only to be told it had happened on Thursday the 19th. “But it said ‘next Thursday’!” you insist. “Right, and the next Thursday to November 15 is the 19th.”

But c’mon. If I’d said, “Next Monday,” you’d have known for sure that was the 23rd, because Monday 16th would be “This Monday.” Right? At what point does “next” go from one week ahead back to the literal “next”?

More or less?

We get into the same sort of trouble when quantifying savings. The lede in last Saturday’s — that is, eight days ago (November 7) — Times Standard read, “Water Use Numbers: Three local suppliers below required conservation mandate.”

“Great,” I thought, “we’re saving more water than the state requires us to.” The body told a different story: “…three Humboldt County suppliers — Fortuna, Arcata and the Humboldt Community Services District — did not meet their cumulative conservation mandate for the four-month period.”

Move the date forward

Another crazy one is the business of moving the date forward. “That meeting we had scheduled for Wednesday, can we move it forward a day?” “Sure, see you on Tuesday.” “No, no, I mean forward a day, not backwards. I want to meet on Thursday…”

See you this next Sunday!

CLICK TO MANAGE