I like almonds as much as anyone – they’re high protein, healthy snacks. And with California producing four-fifths of the world’s almonds (mostly for export to China and Europe), it’s hard to Just Say No to the State’s farmers. But something has to give—the water to grow them isn’t there anymore, and one year’s El Niño (assuming it does materialize this winter) isn’t going to do a whole lot, either for the State’s surface water or underground aquifers. Water’s running out — not tomorrow, but now.

Surface Water

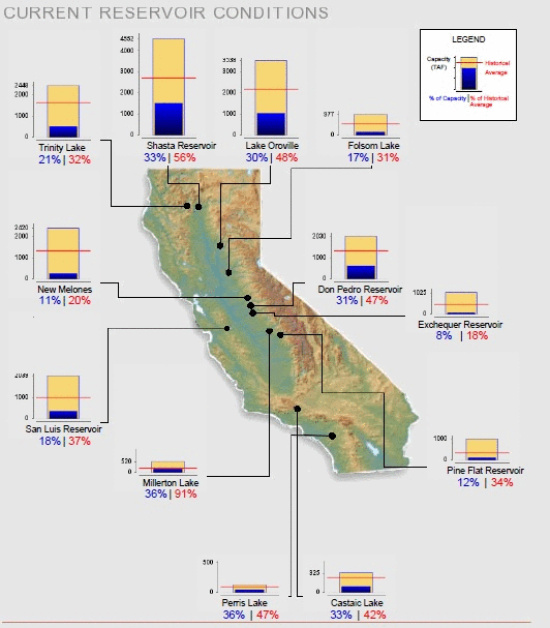

We’re just back from a couple of weeks in Yosemite and the western Sierra foothills in our camper van, where we were able to see first-hand at least part of the problem. Several nights, we parked adjacent to reservoirs – or what would have been “adjacent” a few years ago. After four drought-ridden years, the water levels were down, way down. Boat ramps ended short of the water, vegetation was growing on what had recently been lake bed, and bridges built with the high water level in mind looked like lonely mistakes on their exposed, spindly piers. In mid-October, California’s major reservoirs were at 27 percent of capacity, overall.

Take the State’s sixth largest reservoir, New Don Pedro Lake, some 40 miles downstream of Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy on the Tuolumne River. In addition to generating power from a hydroelectric plant, the Modesto and the Turlock Irrigation Districts irrigate hundreds of square miles of farmland in the Central Valley using the lake’s stored water. Normal high water level is 830 ft., which generally drops to about 760 feet in October. Today, though, the water is way down – around 630 feet – with the lake at less than one third of its capacity.

Aquifers

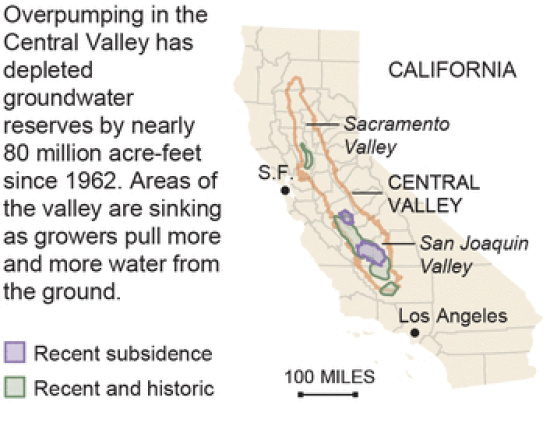

Not all the water needed to irrigate farms in the Central Valley comes from runoff, of course. Farmers far from canals and irrigation channels, without ready access to surface water, pump from the 400-mile-long aquifer that lies beneath the San Joaquin and Sacramento valleys. Over 100,000 wells tap into water that seeped into the aquifer tens of thousands of years ago. Much of it is used to irrigate California’s one million acres of almond orchards. Because water is being extracted much faster than rainfall can restore, the Central Valley’s water table is dropping faster than ever, typically by about ten feet a year, but in some places much more. Over the past 100 years, wells have brought about five Lake Meads-worth of ancient water to the surface.

It’s not that the aquifer is in any danger of running dry soon; it probably still holds 85 percent of water that was there when white settlers began farming and pumping. But wells are going deeper and deeper – 500’ deep wells are now a thing of the past, and 1,000’ wells are now commonplace. At some point, perhaps at the 2,000’ depth, the economics of pumping will cause orchards to be abandoned. Even now, deep water produces its own set of problems; high alkalinity and mineral content calls for expensive treatment before it can be used for irrigation.

Another problem with the depletion of California’s aquifer is that it can never be totally replenished – once water is sucked from clay beds, the fine-grained material compacts (hence subsidence) and doesn’t have the same water-bearing capacity it had before pumping. Not that it’s likely to be replenished anyway – the past 150 years have been much wetter than average conditions over the past three millennia. Southern California is probably heading back to its normally arid climate, global warming or not.

Areas of subsidence in the Central Valley (CA Department of Water Resources/USGS)

One Gallon per Almond

With all this increasing lack of water, you might think farmers would hesitate before planting such water-hungry crops as almonds: a single almond uses about a gallon of water (a walnut needs about five gallons). But apparently that’s not how California’s $5 billion almond industry sees it. We encountered miles and miles of newly planted almond groves, testament to the doubling of the State’s almond orchards in the past decade, to keep up with domestic and international demand. And an almond tree, once planted, will die if it’s not watered.

So you may want to enjoy that healthy snack or glass of almond milk while you can. The good times are running out.

CLICK TO MANAGE