Maybe it’s the geographical isolation.

Or the remnants of our old nuclear plant? The thick and wafting fog of marijuana smoke that hangs drowsily over all our heads, a low psychedelic ceiling that makes residents take the long view when distractions — like good jobs, disposable income, economic development — come tapping at our upstairs window?

Whatever the reason, Eureka nurtures a certain kind of creative spirit, hosts a motley collection of eccentric artistic savants both young and old; it’s this wide and roiling current of wild mind here that fosters so many aspirations, so many weekend dreams, to fruition.

While the atmosphere here may, like so many chemtrails, seed people’s minds with the occasional good idea, it’s the crowds of people — of every type and aesthetic disposition — who emerge from their clapboard hovels in the trees to work your idea, spend countless hours believing in your project and fighting for your project, who linger for the after party.

With a good crew, the difficult suddenly becomes possible; momentum has a mind of its own.

Case in point: Something in the dank newsroom air almost ten years ago made me agree to take on the savage, unholy task of directing a feature-length film. Because I’d worked for a TV station, and directed morning newscasts at KVIQ in the late 1990s, the screenwriter Chris Durant thought I might make a good fit.

Coworkers whose two desks were shoved together so tightly that it was anyone’s guess where my food wrappers ended and his empty Rock Stars began, we hatched the plan with confident nonchalance.

“Fuck Hollywood,” he said. “We’re going to introduce them to the other end of the state.”

Because I was already convinced of my own latent genius, a condition common to many Eurekans, I immediately said yes. This decision, fueled by natural optimism and an ego drunk on its own fumes, would dominate my life for the next two years.

Action.

It takes a special kind of fool to think he can pick up an artistic medium of vast scope and detail, learn the basics on the Internet and by skimming rather vague though well-intentioned books and magazines, and deliver a masterpiece. Or, at the very least, a cult stoner classic.

But again, Eureka fosters belief. As soon as I’d said yes and sought help, I found it. Everywhere.

Good friends took roles on the crew and in the film, the equipment already belonged to a member of the posse, and a coworker at the Times-Standard offered up a chunk of her retirement to fund the endeavor.

Full of hope, and by now a little terrified, I scratched out a list of everything I believed necessary for successful completion. And from that point on, until production began in earnest, we moved methodically down the list, accomplishing one seemingly impossible task after another.

We held a casting call in a downtown dance studio, and hundreds came. Young, hairy, handsome, petite, half-dead, corpulent, old and exotic, they lined up in the halls and out the doors to land a role in our movie. Thrilled by this support, almost overwhelmed, the crew barricaded itself upstairs in a drafty loft to watch people read their excised bits of dialogue and smile pretty for the rolling camera.

Our leading role was already taken, of course.

Hoping to absorb a bit of his long career’s happy magic, Emmy Award winner Jack Hanrahan, a writer for “Laugh-In” and “Inspector Gadget,” was cast as our hero, Jack Snyder.

A first name turned out to be one of the more minor, less troubling similarities the two men shared.

I say he was cast, but in actual fact, the man was adamant that the role be his. He’d read the script as a favor to Durant, and called him up shortly afterward to declare his affection for the film and its protagonist.

It was his support that offered us credibility, at least in our own minds. Though he’d already reached the pinnacle of his career and had in fact been riding a steep decline in fortunes over the last two decades, and despite his advancing age and ill health, accompanied occasionally by erratic behavior, he made it possible to believe in ourselves.

After we’d parsed all the audition footage, assigned more than 20 roles to the best performers, and organized rehearsals, the breadth of our local talent reservoir was made plain. Local theater stalwarts and dramatic neophytes alike, each of those chosen had the skill or raw talent enough to do this, we knew.

Failure wouldn’t result from their shoddy work. They had the goods.

They weren’t the only ones.

All down my list, local people and businesses offered up their storefronts and lobbies, their inventory and services, to help us get our movie made. At any one of these early stages, a refusal of assistance could have sunk the project, drained our coffers and our enthusiasm.

Instead, people here leapt at the chance to help, bent over backward for a chance to sponsor their name into the credits or just be involved. Sets, locations, props, gear, everything virtually, fell into our laps through their excited support.

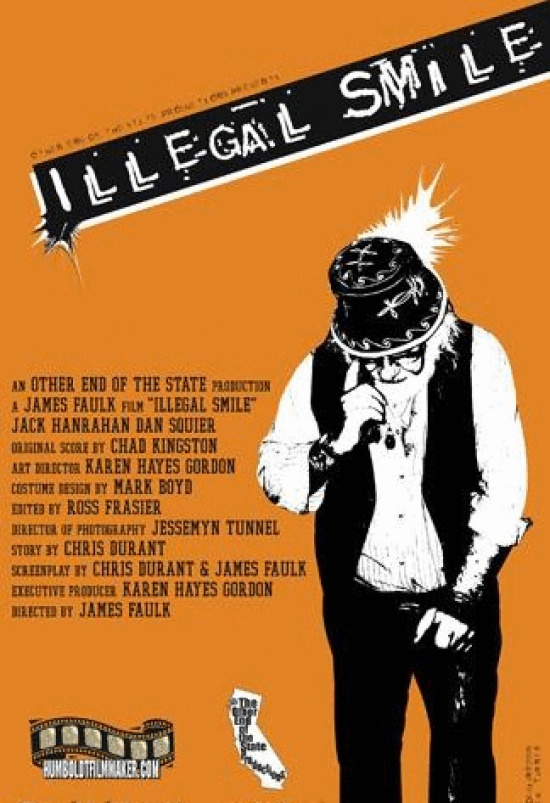

“Illegal Smile” was off the ground, and though it eventually landed with much fanfare and a packed house at the Eureka Theater, it simply isn’t very good.

No, really.

But now, after some distance and humbling reflection, that’s almost an afterthought.

Despite countless challenges, delays, crises and breakdowns, the winnowed crew and I hauled this gargantuan, bloody creation across the finish line.

We followed through.

We learned what was possible given determination, vision and support. We also discovered that enthusiasm and confidence have their limits. Bravado can only get you so far.

Yet we persevered.

Soaked to the throat in a frigid ocean wearing a handmade fish head and red Target polo.

On our third reshoot at a McKinleyville pet store where the odor made our eyes leak real tears, and the resident deputy dog didn’t like us.

Trailing an ATV around the narrow streets of King Salmon, shooting and reshooting an early sequence to make sure the antlers made the shot while never distracting from the scene.

Finally discarding the cue cards after figuring out that our lead actor had a harder time reading than remembering.

Ultimately, we failed as storytellers, and our film is poorly shot and often disconnected. But we flourished as friends and collaborators, and learned the hard way how to manage complex projects in the face of scant resources and little experience.

We learned that collaboration is key, and that pharaohs didn’t build shit — it was all the rock jocks, sweating and huffing inside their burlap skirts and deepening tans, that raised the great pyramids.

Better yet, we came to know and depend upon this little bundle of bayside burgs, sandwiched so tight between mountains and the sea, to finish what often seemed an impossible yet worthwhile task.

Through that process, I fell hard in love with where I live.

###

James Faulk is a writer living in Eureka. He can be reached at faulk.james@yahoo.com.

CLICK TO MANAGE