PREVIOUSLY:

###

Jim was a swaggering cowboy, his distressed leather shitkicker boots falling long and hard out of his stone-washed jeans, feathered hair parted meticulously along the flattest part of his skull.

It was natural, and so was he.

He was also lean like a rodeo star, buckled to the belly button under a .925 longhorn steer. He claimed Texas and the rebel flag, Billy Graham and all that Baptist rigamarole.

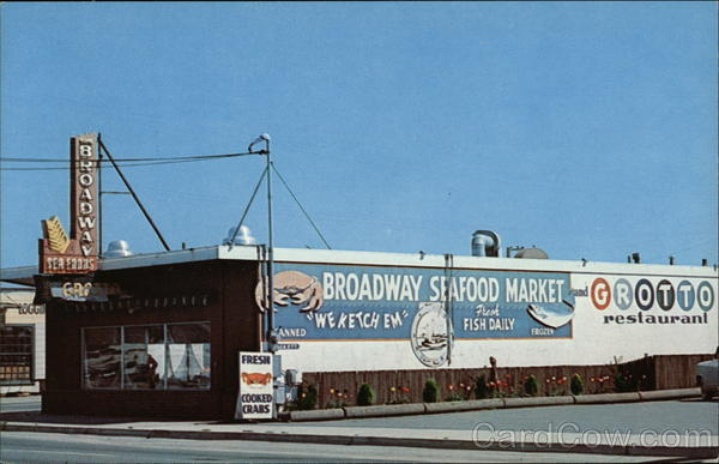

Somehow, this throwback left his Lone Star state and moseyed up the highways past parched deserts and low hills, under the long-shadowed redwoods that gird our corner of the world, until he washed up at Eureka’s 6th and Broadway. Fifteen minutes after his A-Team van rolled into the triangular parking lot, his wicked tongue worked its standard miracle and landed him a job at the Seafood Grotto, as well as a date with the prettiest waitress on the floor.

He’d mumbled something to Dale the manager about qualifications, life on the road and the ephemeral nature of references and resumes. He claimed a five-star pedigree, a taste for mackerel and a wicked spatula backhand.

Dale, fresh out of talent since Steve the Cook had fallen off the wagon and face-first into the mud, blinked his weepy eyes and nodded his head. That was all the permission old Jim ever needed.

The con lasted, as these things do, for far too long. When someone challenged Jim or any of his odd behaviors, he’d swell up like a porcupine, launch into one or another wild tale of his past serving as the black-belted bronc-busting chef of East Austin serving fried zucchini to Asleep at the Wheel, shit on a shingle to old Willie and Waylon.

He had a story for every occasion. Vietnam had taught him that coffee grounds in a bleeding wound would staunch the gore and save lives in a pinch. Three hours in an emergency room taught me well that this was absolutely not the case.

Serving slop on an Alaskan crabber had taught him the value of Worcestershire. And the well-heeled Peterson sisters had reminded him of a lesson he’d first learned working on an oil rig in the gulf: Don’t shit where you eat.

And don’t eat with your hands.

Despite those last lessons, Jim spent a lot of time in the Grotto’s grimey head. When the dining room filled up with blue hairs. When waitresses were forced to flick roaches off their sleeves while serving the owner’s family. When his waitress girlfriend snuck a steak knife from the kitchen and came hunting for his head.

Either one would do, she said, as she prowled the back halls and porch in search of her pleated playboy.

It was after one such incident, when Jim had disappeared from the kitchen and couldn’t be found, that my political principles were put to the ultimate test.

In a cupboard by the back door, Mission Linen habitually stuffed mounds of our white work shirts, along with aprons, towels, wash cloths and sundry other supplies that required a weekly boiling.

As a fishmonger working the back counter, I’d often go through two or three shirts a day. Scales and blood spray had a way of piling up, and the stink got to me. One evening in early January, after spending several hours ripping crabs apart and tossing their insides into a squelching garbage can, I was in search of a fresh uniform. On top of a teetering stool, all 250 pounds of me hanging precariously over the edge, it took a moment for me to register the hairy hand on the back of my leg.

Agility has never been my strong suit. Be that as it may, I pirouetted just fine to find the lean mug of Cowboy Jim staring up at me. His eyes were shining, his lips parted just enough to see the black bits of tobacco that stained his front teeth.

“I like big men’s thighs,” Jim said, grinning like a fool in a half-hearted way to make this thing a joke, if it suddenly needed to be a joke.

Despite years of professed liberal leanings, and a finely honed tolerance for other people’s get down, I’m almost ashamed to say I slapped his creepy hand away and skittered half up the wall and ceiling to somehow get around him and out of that enclosed space.

In scant seconds, I was ensconced behind the well-lit fish case sharpening my knife and preparing for battle.

It never came. Jimbo never mentioned his pass, and I never let him. As soon as it became clear he and I were approaching any kind of solitude, I’d find my spider legs and make haste for my glass fortress at the back end of the restaurant.

Weeks later, the strange charade came to an end. Dobber, the manager’s pet favorite and supervisor of the fish market, was freshly returned from a self-inflicted knife wound of his own, earned in the course of a romantic dissolution with waitress Donna. She’d taken an interest in a shuffling busboy named Carl, and Dobber wasn’t ready to let her go.

In a grand act of cowardice, he proclaimed his feelings to a dining room full of patrons before plunging said knife as hard as he could into his torso. Several women fainted, three bowls of chowder hit the floor, and every roach in the building took cover where it was found.

Lucky for Dobber, the butter knife proved too dull to break the skin. He spent two weeks on emergency medical leave, while Donna and her busboy Lothario caught a Greyhound headed north.

Dobber’s first day back, Jim exploded out of the kitchen at a trot, slamming open fish case doors and rifling through the merchandise. He’d run out of salmon for the day’s special, and needed fresh meat fast.

This of course violated Dobber’s number one rule of operations: Our inventory is not their inventory. If the kitchen needed fish, they had to buy it like everyone else. Jim grabbed a salmon by the tail, while Dobber caught hold of the front end, his fingers luckily laced through the gill.

It took Dobber only two seconds to win that tug of war, and when he found he alone had ownership of the now floppy fish, he cracked again. Like a rioter in the streets, he clobbered Jim upside the coiffed head, then again on the back and shoulders, knocking Jim off his feet.

He landed several more blows before the manager and I could pry him loose. Seconds later, Jim was staggering but on his feet long enough to rip off his apron and throw it to the ground.

Spitting out bits of pink meat, he gave an impromptu — and entirely incoherent — speech referencing Confederate General Stonewall Jackson before stomping crookedly from the store.

We watched him limp to his van and climb inside, the engine roaring to life in a strange display of automotive ferocity. Tires squealed as he tore out of the parking lot and into traffic, half-heartedly clipping an old man walking his dog.

Not knowing what else to do, I handed Jim’s bootheel to Manager Dale.

He arched an eyebrow.

“Dunno,” I said. “I think he lost it in the melee.”

###

James Faulk is a writer living in Eureka. He can be reached at faulk.james@yahoo.com. Some name have been changed to protect the guilty.

CLICK TO MANAGE