“People who are

oppressed or suppressed need an outlet, so they write on walls. It’s

free.”

—Terrance Lindall, Director, Williamsburg Art and Historic Center

Photoshop-inverted graffiti behind Bayshore Mall. (All photos Barry Evans)

I have a love-hate relationship with graffiti. The love is appreciation for artistry, color, form, humor — everything that goes into creating a personal work of art in a public space (usually illicitly). The hate is for ugly tags and obscenities with no discernible motive other than antagonism, a desire to offend and desecrate, especially — this is where it really gets to me — when it’s done on bare stone, meaning it can’t be erased without sandblasting.

(This is a real issue in Guanajuato, Mexico, where we spend part of our lives. The UNESCO World Heritage city is known for its “canterra,” a green-tinged copper-infused sandstone quarried from the surrounding hills. Over time, the stone acquires a hard patina on its surface, protecting it from the elements. Sandblasting removes the veneer, making it vulnerable to erosion.)

Wildstyle graffiti, Verona, Italy

Seems the Powers That Be have an ambivalent reaction. For example, for years, Humboldt’s five orphaned locomotives sitting at the east end of the Balloon Track next to Waterfront Drive were ennobled by graffiti — not anything that would have passed an art critic’s muster, but colorful and not (to my uncritical eye) offensive. But after years of toleration: “Hey, that’s like, anarchism, right?” So They (someone with enough money to pay for the paint and to rent an industrial spray gun) covered it all over with a sort of puke-green color. Now we have five ghost locomotives. Awaiting the next round of, um, artistry.

Graffiti has been with us forever, apparently. Wikipedia helpfully has pics from ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome, including — from Pompeii, RIP 79 AD — directions to the local brothel, complete with a price list. I was shocked (I was more naive once) too see that Lord Byron, lauded as a great poet in the UK, not so much in the US, had scrawled his name 200 years ago on an otherwise stately Doric column, part of the remains of the idyllically-sited temple of Cape Sounion, not too far from Athens. (The gods had their revenge — he died young in Greece of fever.)

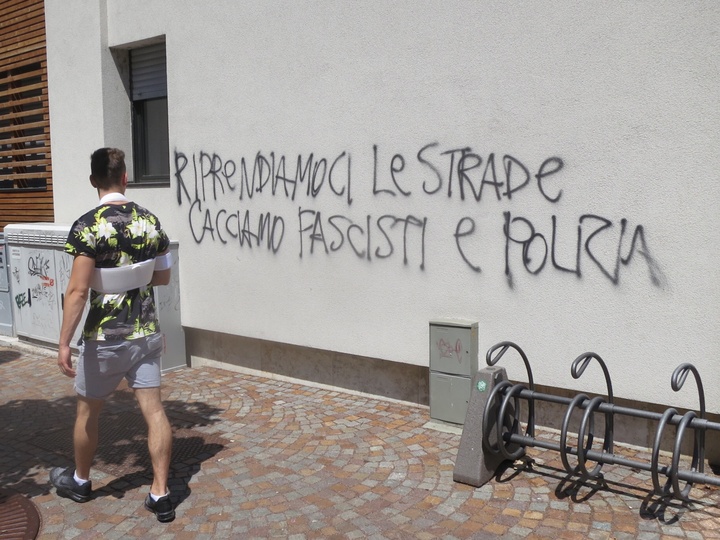

Loose translation: Take back the streets, kick out fascists and police. (Trento, Italy)

Louisa has her own system of dealing with local graffiti in Guanajuato. Trusting the “broken window theory” that says garbage and graffiti attract more of the same, she satisfies her urge for harmony and security by covering up the previous night’s gang tags and wildstyles (interlocking letters) within hours of their creation. And it works! Graffiti in our neighborhood is way down.

In an “If you can’t beat them…” approach, many jurisdictions set aside dedicated urban zones where graffiti isn’t just tolerated, it’s encouraged: Taiwan, for instance, or closer to home, “Art Alley” in Rapid City, South Dakota. This means that spray-paint artists can spend as much time as they want to create their masterworks, without the constant fear of being caught. Unless of course, that adrenaline-laced fear and urge for dissidence is actually the incentive to spray graffiti in the first place.

St. Jerome (?), Verona, Italy

Vandalism or street art? Your call. And if it really bothers you, get out there with matching paint and solvents and do some anti-graffiti of your own.

CLICK TO MANAGE