There

comes a time when one asks, even of Shakespeare, even of Beethoven,

“Is that all there is?”

Well yeah, Beethoven, but what did he know? My money’s on Sergei Rachmaninoff, of whom I will never, ever, ask, “Is that all there is?”

Last night (it’s early Saturday morning) my body sat fifteen feet away from soloist John Chernoff as he dazzlingly bravura’d through Rachmaninoff ‘s Second Piano Concerto. It’s an astonishing work, the Russian composer’s most popular piece, used on the soundtrack of countless movies; astonishing because half the time the orchestra accompanies the soloist, the other half the piano is accompaniment to the orchestra, all the while with a zillion changes of key. There must be gazillion individual notes in the long concerto, alternatively thrilling and moody, unruly and scary. I like to think Rachmaninoff wrote this piece (in 1900) to celebrate emerging from a four-year long depression: the music had been inside his dark self all along, and now it was uncaged in the light, free at last.

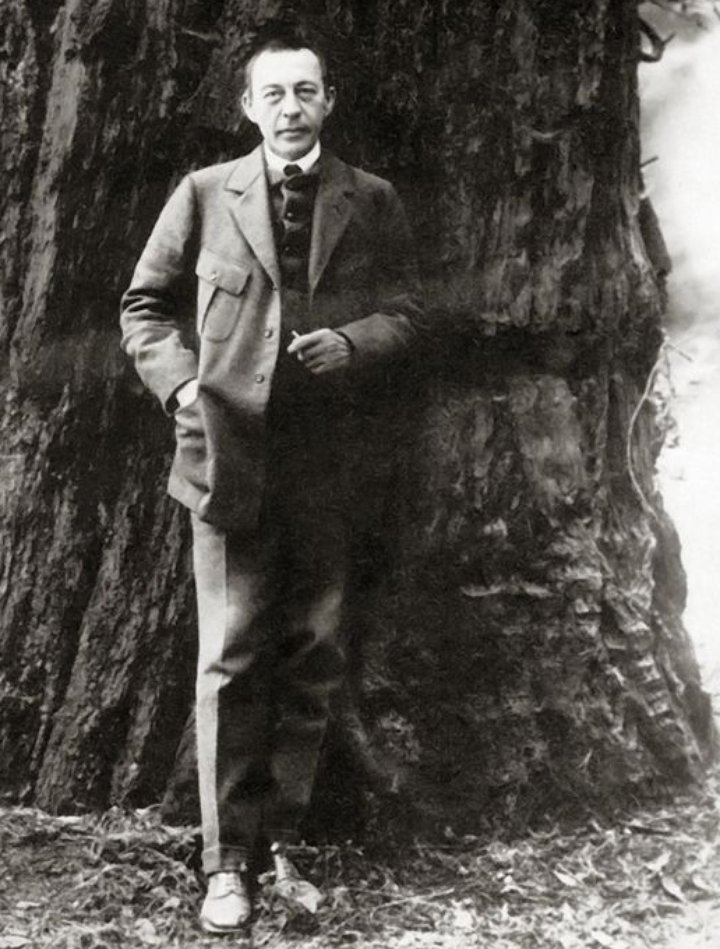

Sergei Rachmaninoff, in 1919, aged 46 in front of a redwood tree near San Francisco. He acquired American citizenship just before his death in Beverly Hills in 1943. (Unknown photographer, public domain)

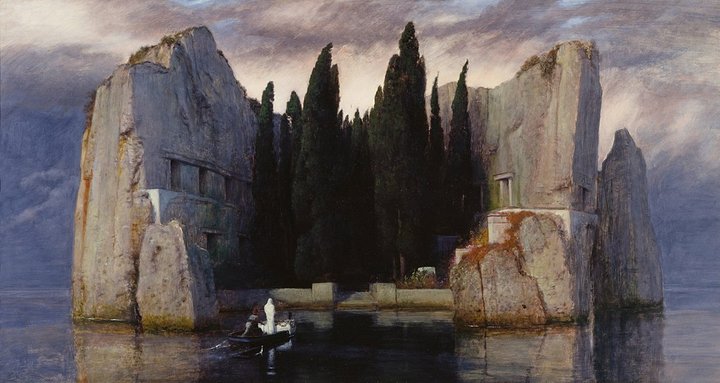

(It’s not my favorite work by the “last of the Russian romantics” — that would be his tone poem “Isle of the Dead” or his Third Piano Concerto, both written about a decade later. The latter is the one you play if you want to win a virtuoso piano competition, as hard as they come, apparently, immortalized in the movie “Shine” that resulted in the 1996 Oscar for Best Actor for in Geoffrey Rush.)

A black-and-white version of Arnold Böcklin’s painting “Isle of the Dead” inspired Rachmaninoff’s symphonic poem of the same name. (Public domain)

So that’s where my body was, left front, Arkley Center, Friday night. My mind, though, was far away and long ago, sitting in Jenny Hay’s living room in my hometown in southeast England. I must have been 12 or 13, during my early puppy-dog adoration stage for Jenny (which has never abated). We’re sitting in front of the coal fire on a cold winter’s night, Jenny and me on one side of the fireplace, her mum and dad on the other. We’re listening to Rach-2 on Mr. Hays’ hi-fi—he’d just bought the piece on one of those new-fangled 12-inch LPs — in total silence. You didn’t talk when Jenny’s dad played his music. It ended and he finally broke the enormous silence, looking deeply into my eyes, his face wild and tear-riven. “Doesn’t that music reach into the depths of your very soul, Barry?” He asked. I wasn’t sure I had a soul, let alone its depths, but I recall replying emphatically, “Oh yes, sir.” No way was I going to argue with my beloved’s dad.

Finally, my point: music maketh memory. Actually, listening to the music last night, that scene was more than a memory: it was as real as the cup of coffee in front of me now. The brogue of his Aberdeen accent, the warmth of the fire, my feeling of ineptitude not understanding what he meant, Jenny’s cornflower-blue cotton dress — I was there. And I know you know what I mean because it’s universal, this music-memory connection. Therapists use it to evoke past experiences in their patients, doctors bring Alzheimer’s sufferers relief by helping them remember their earlier lives. Bards of old didn’t just recite the epics and eddas, they chanted them for ease of recall. It’s all in the limbic brain, I understand. (Not true, I don’t understand, but I can sort of imagine the ancient brain stem being aroused by rhythm and undulation.) According to UC Davies neuroscientist Petr Janata, “What seems to happen is that a piece of familiar music serves as a soundtrack for a mental movie that starts playing in our head.”

Apparently pop songs from when we were in our early-to-mid-teens have the greatest memory-invoking effect. Play Del Shannon’s “Runaway” or the Don and Phil’s “Dream” or Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” or Elvis’ “A Fool Such As I” and I’ll give you chapter and verse: where I was, whom I was with, my state of mind, the weather. Don’t be angry with me if I cry.

You too, I bet.

CLICK TO MANAGE