As a part of a plan to slash a whopping $9 million from the budget over the next two years, administrators at Humboldt State University have proposed a change in how lecturers and faculty members get compensated for teaching large classes.

For many years now, instructors who teach courses with 75 or more students have been awarded extra credit in the form of “weighted teaching units,” or WTUs. Just as students get credit for the number of units they take each semester, instructors are paid based on how many weighted teaching units they carry. So if, say, a biology professor has a class with 96 students, she could receive two extra WTUs. If her class has 125 students she could get three extra WTUs. For more than two decades these bonus units have been viewed as fair compensation for the extra work that goes into teaching so many students.

But administrators have proposed changing this practice starting next semester. Rather than being awarded with extra WTUs, instructors with large classes would be assigned student teaching assistants to help them with the extra work.

While this hasn’t been common practice at HSU, it is technically the policy that’s on the books — and has been for nearly 25 years. A 1993 memo spells it out: “For classes with census date enrollment of between 75 and 120 [students] and exceptional workload, a graduate assistant or student assistant may be allocated.” Bonus WTUs are only permitted when there’s no teaching assistant available, according to this policy.

The proposed change in practice, reverting back to the policy as written, is expected to save the university between $355,000 and $375,000 during the 2018-19 academic year, according to university spokesperson Frank Whitlatch. “This support model is utilized at hundreds of universities across the United States,” Whitlatch said via email.

But faculty members are up in arms. More than 20 grievances have been filed through the California Faculty Association (CFA), and they say their objections are about more than the cuts to their “already absurdly low” pay. They say this change will harm the student learning environment.

“My worry,” said Loren Cannon, chair of the HSU chapter of CFA’s Faculty Rights Committee, “is that when they do cuts, like with these WTUs, it overworks faculty members, [which] results in lowering education quality.” [Disclosure: Cannon is a personal friend of this reporter.]

When tenure-line faculty sign up to teach more classes — in order to teach their “full load” as it has been re-defined — it will leave longtime lecturers without enough classes to qualify for health insurance, Cannon said. “Some are just losing their jobs completely,” he added. “This is how the university ‘saves’ the money. The tenure-line folks are overworked, lecturers are overworked, and some lecturers go without benefits or a job.”

Cannon believes teachers and students are paying the price for years of mismanagement, and others agree.

Earlier this month, Jane Monroe, a lecturer in HSU’s Department of Biological Sciences, wrote a letter to President Lisa Rossbacher, accusing her and fellow administrators of trying to fix the budget “on the backs of some of the lowest-paid people on campus.”

“Cutting our pay is demoralizing, insulting, and detrimental to our students,” Monroe wrote. “The pay cut means that I will make about $30,000 next year, which is not a living wage. I will have to take a second job to make ends meet. Therefore I will have far less time and energy for the two hundred students I educate each semester.”

Monroe suggested that rather than cutting teachers’ salaries, “perhaps a five percent pay cut to any administrator making over $100,000 a year would help with the so-called budget problem.”

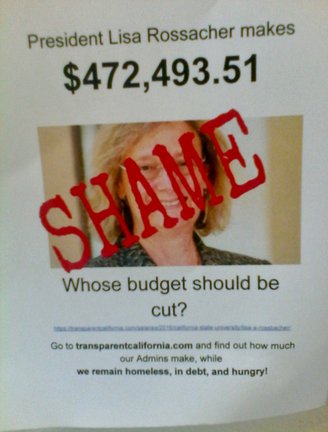

A student flyer shows the total pay and benefits earned by HSU’s president in 2016, according to the online database Transparent California. Her salary is currently $327,181.

Administrator pay has been lambasted by student protesters, too. They’ve hung flyers on campus with the word “SHAME” stamped across Rossbacher’s face, and other flyers (including this one) showing administrator compensation as reported on the online database maintained by Transparent California.

But Whitlatch said HSU has already eliminated three administrator positions, and the budget plan calls for cutting another 14 administrator and staff positions in the short term, plus an additional 30 in future years.

Whitlatch also pointed to the university’s budget FAQ page, which notes, “Based on employee data from Fall 2016, the number of administrators at HSU has declined from 86 to 79 over a ten-year period.”

Over that same period, administrative positions across the California State University (CSU) system increased by more than 16 percent.

As for Rossbacher specifically, her current salary of $327,181 puts her just below average among presidents in the CSU system. And Whitlatch said executive compensation in the CSU system is below market compared to similar institutions.

In 2014, the average public college president in the United States earned just over $428,000. In the CSU system four years later the average is about $334,000.

When the university announced its 2018-19 budget, Rossbacher dubbed it a “students first budget,” but instructors insist that the proposed change in practice will erode the quality of students’ education.

Alisha Gaskins, a lecturer in HSU’s Department of Anthropology, told the Outpost that while the practice of awarding an extra unit for teaching large classes “is apparently not common practice in the CSU or in universities in general, it has allowed me to provide a more meaningful, responsive, and effective education for the last three years at HSU.”

Gaskins has filed a grievance over the proposed change, and in a statement prepared for an on-campus inquiry into the issue she argued that a student teaching assistant could be more of a hinderance than a help. When a former student volunteered to fill that role last semester, Gaskins felt compelled to personally oversee the volunteer’s work in grading papers.

“This isn’t because she didn’t do an amazing job,” Gaskins wrote. “It’s because I ultimately feel responsible to assess student work to gauge if students are understanding the key concepts in our course … . Through this trial run, I learned that having to oversee someone else do the grading is actually more work for me.

Cannon said many instructors feel the same way. In an informal survey of faculty members conducted earlier this year about 80 percent of respondents said that having a teaching assistant would not offset the extra workload in big classes, and would instead impede on other professional tasks.

“There is no evidence that these kinds of measures increase student learning,” Cannon said.

Whitlatch disagreed. “The model of integrating student assistance is being used very successfully already in some departments,” he said. The model is being utilized in many other four-year universities with graduate programs, too, and Whitlatch suggested that the lack of evidence cited by Cannon cuts both ways. “There is no evidence that having a TA adds to faculty workload,” Whitlatch said.

The grievance process, as spelled out in the current collective bargaining agreement, is generally lengthy and involved. and it may be complicated in this case by the fact that the written policy differs from longstanding practice at HSU. As things currently stand, the change in practice is set to take effect in the upcoming fall semester.

CLICK TO MANAGE