If you lose a prescribed fire, your career is probably on the

line.

– Stephen Pyne, Fire Historian, Arizona State University

###

Last week, my quick-and-dirty commentary on the California wildfire situation (bad, getting worse) blamed human-caused global warming as the primary culprit of today’s “new normal” fires. California’s record three-digit July temperatures resulted (almost certainly, science doesn’t deal in 100% certainties) from the three parts per million of CO2 that we’re adding to the atmosphere every year. However, even if we stopped burning fossil fuels cold-turkey, the damage is already done: we’re in for a long period — centuries! — of increasing global temperatures. Short term, the best we can do at this point is to convert — fast — to non-carbon-emitting energy sources.

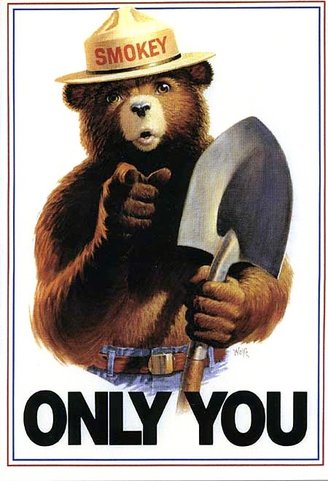

Sorry Smokey, prevention isn’t always the best policy..

However, other problems are responsible for the hotter, larger and more frequent wildfires that I didn’t discuss last week. They include:

- Nearly a century of absolutist fire suppression policy by the Forest Service. The “10 a.m. rule” (the goal of extinguishing every wildfire by 10 a.m. the day after it was reported) was instituted following the 1910 “Great Fire” (or “Big Blowup”) that burned nearly five million square miles of Idaho, Montana and beyond. This inflexible policy has altered the natural fire cycle, leading to a vast build-up of flammable underbrush and dead trees. Previously, low-intensity fires were the norm every decade or two. Sorry Smokey, your prevention policy was — and is—dead wrong. And according to a paper in Nature (6/26/17), lightning causes most fires, not humans.

- Little focus on prescribed, or controlled, burns to clear out dead brush and ward off invasive species. The Forest Service started prescribed burns in the 1940s, but on a very limited scale, and, as indicated above, they present dangers of their own. (A prescribed burn in Colorado in 2012 that got out of control and killed three people led to a five-year moratorium in that state.) Here in California, it typically takes CalFire a year to obtain CEQA approval for a prescribed burn — unlike, for instance, in Florida, where such burns are the norm: over 3,000 square miles annually, compared with 31 square miles in California, according to Stephen Pyne, quoted above.

Controlled burn in ponderosa pine, eastern Washington (USFWS - Pacific Region, Creative Commons)

- The current focus — -including state budget money — on fighting fires, rather than preventing them in the first place.

- Traditional clear-cutting practices. Modern forestry management calls for thinning trees, rather than clear cutting, but this is a comparatively recent practice. Compare Maxxam’s destructive maximum-bottom-line approach versus Pacific Lumber’s (mostly) sustainable forestry practices. PLC was, of course, a family company, while Charles Hurwitz’ Maxxam is a predatory mega corporation.

- The invasion of bark beetles in the West, resulting in millions of dead trees creating what Mark Finney of the Missoula Fire Sciences Laboratory calls “a giant heap of dead forest.” He goes on, “The fuel conditions we’re seeing have implications for fire behavior beyond our current understanding and models.”

- Increasing amounts of deadwood leading to “spotting”: hot embers picked up by the wind and being scattered a mile or more ahead of the fire line. (Idaho’s 1967 Sundance fire sent embers eight miles ahead of the actual flames.) Most houses are set afire by embers, not by the actual flames, thus “pretty much render[ing] fire containment impossible,” according to Dr. Finney.

- Highly flammable homes, often with wood shingles (!), built in the wild/urban interface (it being way cheaper to build out in the country than up in urban areas). Check out CalFire’s readyforwildfire.com to improve your chances if you’re living in one such house.

- Drought. While droughts are part and parcel of California’s ecology (you can make a good case that the last hundred years of our comparatively wet climate is an aberration), they’re getting longer and more severe. The current drought is now six years old.

And on and on. Last June saw the first meeting of the Forest Management Task Force (initially announced by Jerry Brown in his January State of the State address), which, one hopes, will look at these issues. I hope priority will be given to clearing dead trees, removing dry underbrush and thinning the unhealthy stands created by previous clear cutting.

Bottom line: Even thought a stable climate system is a thing of the past, we can still do a whole lot better with forestry management practices.

CLICK TO MANAGE