My wife Louisa Rogers has been following the latest Catholic priest abuse scandals, particularly regarding the complicity of those who knew, but did not speak up. This is her guest column:

About ten years ago, I attended a committee meeting of a spiritual group I belonged to. During the meeting, one of the senior members, a man with great standing in the group, got furious at another member, blowing up at her. She hadn’t been observing the best meeting protocol, it’s true—she had jumped in to speak before he was finished. But we had all been interrupting each other; she was just the latest. He yelled at her while the rest of us sat there in stunned silence. I was so shocked by his rudeness that I said nothing.

On my way home, I tormented myself. Why didn’t I speak up? It was uncalled for, how he had treated her. Later I phoned her and apologized for not intervening on her behalf. And I told the committee chair we needed to create guidelines for how to communicate in meetings so that this would not happen again. It was the least I could do. But I still cringe when I think of my silence.

Another time I didn’t speak up: in a crowded bus station in Boston in the late 70s, I watched, horrified, as a guy in his 20s dragged his companion by one of her braids along the length of the bus station floor and out onto the sidewalk. Passengers seated in chairs waiting for their buses, people buying tickets—to my knowledge, none of us acted. I’ve often wondered what happened to that young woman.

In both those situations, I was participating in what’s called the “bystander effect,” the phenomenon in which individuals are less likely to offer help to a victim when other people are present. The greater the number of bystanders, the less likely it is that any one of us will help.

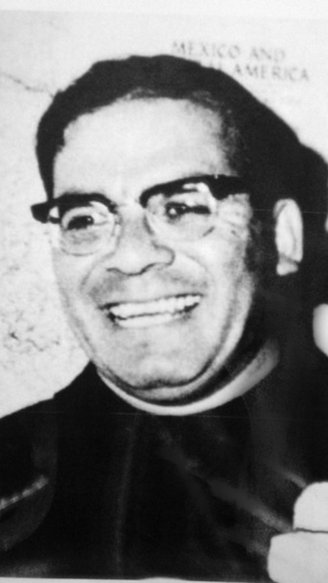

I thought of these experiences recently when I read an excerpt of a memoir called Unspeakable Joy, by Seattle writer Fred Moody. The book describes his adolescent years in a Franciscan seminary during the 60s in Santa Barbara. The priest, Father Mario Cimmarrusti, along with eight friars, were later exposed for sexual abuse that had gone on for decades. The Franciscans paid out millions of dollars in damages to settle civil suits. Due to the statute of limitations, none of them ever faced criminal charges.

Father Mario Cimmarrusti, 1931 - 2013 (Unknown photographer)

Moody was 14 when he and other seminarians, standing in the parking lot outside an open window of the school, heard their fellow student screaming in Father Mario’s room. None of them said or did anything. Fifty years later, he still feels shame at his silence. It wasn’t just the adults who had blinders on, he writes; it was the students too. When he finally brought himself to read the court documents from the lawsuit, he says it was hard to know which was worse: becoming aware of the scope of the abuse, or recognizing the names of some of the victims—those he could have helped, but did not.

Since he escaped the abuse, Moody was one of the lucky ones. But it’s my belief that bystanders also pay a price, even those who rationalize away their participation. I’m not suggesting they suffer to the degree victims do, with the hallmark symptoms of sexual abuse: withdrawal, depression, low self-esteem, and even suicide.

Still, the knowledge that he might have been able to make a difference but chose not to, is painful. Moody points out that his complicity left Father Mario’s crimes undiscovered until after their statute of limitations had expired and helped the abuse to continue for decades, not only in Santa Barbara but throughout the Catholic Church.

But you were only 14! I think. Give yourself a break. How could you have known that the sexual abuse you were privy to in your small world was a worldwide phenomenon?

I think back on myself at 14. I was a ninth-grader at a large junior high school in suburban Washington, D.C. Would I have spoken up in the face of cruelty or injustice? I did tell my mother at age 11 that my grade-school principal, using the word “n***er,” had forbidden a black boy and a white girl to dance the limbo together. But telling her wasn’t much of a risk. When she called the principal, it turned out other parents had already reported it. So much for my moment of whistle-blowing. And unlike Moody, I didn’t have any fear of talking to her.

“Catholic priests were revered figures,” Moody writes. “I couldn’t imagine getting either of my parents to believe anything bad about anyone in the clergy. To give voice to the kind of unease I felt around Father Mario would be to invite opprobrium, even punishment, from my parents.”

At 14, Moody was older than many kids who look away, knowing something awful is happening. It’s a lot to ask a 7- or 8-year-old witness to challenge an authority figure and question the accepted norms. And yet, how do you raise a child not to be a bystander— so they don’t become the bishops and cardinals who hide and protect, or in the secular world, the staffers who knowingly send young stars up to Harvey Weinstein’s suite?

As for Moody, he lives “a complicated sanity: a normal married life, with an astonishing wife and astonishing children, and this secret dark little gnome gnawing away at my heart.”

I feel for him. I hope writing his memoir helped to dissolve the little gnome and excoriate his shame, just as I hope that writing about the times I did nothing will help me act next time.

CLICK TO MANAGE