Yurok Tribal Headquarters in Klamath. Photo: Andrew Goff.

###

For years, rumors of sexual harassment, intimidation and professional misconduct surrounded Javier Kinney. The rumors were known and openly discussed among the Yurok tribal council, employees and members of the tribe. Several women have either told the Outpost or spoken out during a public meeting to say that multiple complaints were filed, but the tribe never fired him. In fact, he was able to attain the position of executive director in December 2018 after being appointed by current Yurok Chairman Joe James.

But Kinney is the now former executive director of the Yurok Tribe, after formally resigning on November 5, one day after a phone call from the Outpost. The press release issued by the tribe that day is direct and to the point about Kinney’s resignation, but it offers little explanation as to why he stepped down. It mentions the tribe’s “sexual harassment policy” but does not go into detail. The press release states that “[H]uman Resources Policies require personnel issues to remain confidential” — something that has proven to be a barrier not only for the press but also for tribal members speaking out.

Something had happened in the days leading up to Kinney’s sudden resignation — some sort of precipitating event. The Outpost has not yet been able to confirm precisely what that was, but on Nov. 1 tribal member Onna Joseph issued a loud condemnation of sexual harassment, obliquely aimed at Kinney, in a Facebook post that garnered wide attention and support within the Yurok community.

“If a man is sexual harassing women and these women are reporting it…he should be held accountable for it,” the post reads. “Losing his job is a start but also counseling and please don’t give him another job within the tribe… .”

A few days later, after Kinney had officially resigned, a meeting was held at tribal headquarters in Klamath. During the meeting, eight women came forward and shared stories of past trauma. They also expressed their frustrations about the lack of action from those in power within the tribe.

Vice-Chairman Frankie Joe Myers opened the meeting with a prayer and thanked “the Creator.” He also told the attendees that due to the tribal Human Resources Policy, people who wished to speak could not name any person involved in a “personnel issue.” Instead, speakers alluded to Kinney, or referred to him as “him.” But one woman did say, “I’m scared of Javier.”

“We all know what the right thing to do is, and that is to exclude him,” she continued. “I fear for my children. I fear for my grandchildren. I quit going to the dances. Exclude him. Enough is enough.”

An investigation by the Outpost has further found allegations of physical, verbal and emotional abuse by Kinney’s soon-to-be ex-wife, allegations of sexual harassment and intimidation by a former employee and what would appear, on the face of it, to be a habitual disregard from tribal management of formal complaints filed by Yurok employees.

During the reporting for this story, the Outpost reached out to Yurok Chairman Joe James, the Yurok Tribal Courts, the Yurok Public Relations manager and other representatives multiple times and in multiple ways, but never got a response back. The Outpost also tried contacting Javier Kinney multiple times after speaking with him in person, but never got a response back.

###

Kinney — then tribal self-governance director — with US Attorney Melinda Haag in 2010. Photo: US Department of Justice.

Javier Kinney was born on Jan. 11, 1974, and grew up in Weitchpec. He graduated from Hoopa Valley High School and went on to get a bachelor’s degree from the University of California at Davis in 1997, majoring in history and Native American studies. From there, his path brought him to Tufts University, where he received a master’s degree in law and diplomacy.

In 2001, Kinney began attending Suffolk University in Boston, Mass. where he earned a law degree. Shortly after graduating from the East Coast school, Kinney took a position with the San Manuel Band of Serrano Mission Indians in Southern California, where he worked as a senior policy analyst.

Kinney eventually returned home to the North Coast in 2008, when he got hired as the transportation manager for the Yurok Tribe. For the next few years he worked to bring infrastructure upgrades to the tribal lands and helped negotiate the purchase of more than 22,000 acres of ancestral Yurok land from the Green Diamond Resource Company in 2011.

Stevie Lemke started working for the Yurok Tribe in March 2015 as the assistant director of self-governance. The director of that department, at the time, was Kinney. Lemke grew up in Portland, Ore., and earned a law degree from Lewis and Clark University. Before her time with the Yurok Tribe, she worked in Washington, D.C., in the Division of Indian Affairs at the Department of the Interior’s Office of the Solicitor. She ended up working for the Yurok Tribe after meeting a friend who was interning with the National Indian Gaming Commission.

In an interview with the Outpost in the wake of Kinney’s resignation, she said the harassment from him started almost immediately.

“Within two or three days he was making comments about how I needed to have my hair pulled back because I had bangs and how it wasn’t appropriate in Yurok culture to have your hair hanging down,” Lemke said. “He liked to close the door and lock me in the office. It was more emotional intimidation than anything.”

Lemke also said a point of contention was the way she dressed. Kinney would tell her that she needed to wear high heels and was particular about how she presented herself. She said Kinney’s actions and mistreatment of female employees were widely known in the tribe, and within the first few months of her employment she had tribal council members asking her if she liked her new boss. At first she thought it was a trick question and stayed tight-lipped about her problems. But over time that reticence wore off.

“I started being really honest and telling council members, ‘Honestly I feel really uncomfortable,’” Lemke said. “[My] position historically was held by younger women and he was primarily known for intimidating women. Everyone complained, everyone complained that he was derogatory.”

Lemke said she got to know two women who held her position before her. She said they told her that they issued formal complaints about Kinney’s behavior and that if she took that route, she should mention their complaints and how Kinney has a history. She eventually filed her own formal complaint against Kinney, but she said nothing really changed because of it.

“The only person who had the power to [fire him] would have been the executive director and that would still have to be done with the consent of tribal council,” Lemke said. She went on to say that former tribal executive director Troy Fletcher assigned her complaint to be looked into by Earl Jackson, the deputy executive director at the time. Lemke said Jackson didn’t take the complaint seriously and chalked it up to being a “personality conflict.”

“I remember telling Earl that it isn’t a personality conflict when it is a conflict with every female that works here,” she said.

Lemke talked openly about her issues with Kinney and her frustrations with having to work under him. She said Rose Sylvia, former director of Yurok Human Resources, knew about the complaints against Kinney. So did Oscar Gensaw, another former HR employee, as well as Don Barnes, director of Tribal Employment Rights Office, and Abby Abinanti, chief judge of the Yurok Tribal Court. But nothing happened.

“When I say that everybody knew, I spoke with absolutely everyone in the tribe about it,” Lemke said. “I was not shy in saying, ‘I am having issues with Javier.’ The whole planning department knew. The whole tribal court knew. The whole office of the tribal attorney knew. I am not exaggerating when I am saying that I spoke with everybody about it.”

Lemke finally resigned from her position on January 8, 2016, at 2:11 p.m. In her resignation letter to the tribal council, Lemke pointed out the “notoriously difficult working conditions.”

The environment within the [Office of Self-Governance] is unsustainable, disruptive, and threatening. Within a month of joining the Tribe, my position within the organization was threatened, and I was bullied by the Director when I chose to take my concerns through the appropriate management levels. The OSG Director regularly flaunts disregard for Tribal personnel policies and procedures, and disparages and bullies female employees of the Tribe. I have attempted to reconcile my concerns and apply for positions within other Yurok Tribal departments without success. It is for these reasons that I feel that I must protect my emotional and spiritual health by pursuing opportunities in a more productive working environment.

Before she left that day, she had to face Kinney one last time. Lemke let HR know she was leaving, but this eluded Kinney until her last day. She was working through a list of tasks that needed to be completed before she left, one of which was to file paperwork to be compensated for $40 she had spent on a trip. Lemke remembers a coworker giving her a hard time about the paperwork and reimbursing the money.

Kinney asked if she had completed everything on the checklist and Lemke told him she was still waiting on the reimbursement. Kinney asked her what the problem was and she told him there was a miscommunication about how the paperwork needed to be filled out and that she was waiting on the fiscal director to reconcile the paperwork. If the paperwork was not filled out correctly Lemke would have been out the $40.

“I was sitting in the self-governance office and Javier came in,” Lemke said.

After he walked in, she remembers he shut the door behind him and walked over to her desk. She remembers he put his hands on either side of her chair, preventing her from getting up. He stared into her eyes and lowered himself to within an inch or two of her face — so close that she could feel his breath.

“He got super close and aggressively said, ‘Are you telling me that you want your lasting impression with the Yurok Tribe to be over $40?’” Lemke said. “He knows how to tip-toe that line where he knows that he is not going to get in trouble, but he is going to make your life hell.”

###

In 2014 Kinney met his second wife, Erika Brundin. Brundin is a local to the North Coast and grew up in Crescent City and Fort Dick. She said she first met Kinney through mutual friends when she was doing roller derby at the time.

“When we first met he swept me off my feet,” Brundin told the Outpost. “He showed me what I wanted to see.”

The two hit it off and married within a year. Kinney was a well-known person in the community at that time. He was a cultural and spiritual leader, but a dark side soon came out.

“He isolated me from my family,” Brundin said. “I started learning that is how abuse starts — slowly. I didn’t quite see it until now.”

Brundin said she was subjected to both physical and verbal abuse from Kinney and that she had to put on a facade because she was a politician’s wife. Although she was never “employed” during her time with Kinney, her role as his wife was a full-time job. She had to entertain guests that ranged from county representatives to state commissioners. She said her main job was to simply stand by Kinney’s side and be his “trophy wife.”

“I am not a trophy wife; I am someone who has a voice,” Brundin said. “I got treated like a pile of shit after his friends went home.”

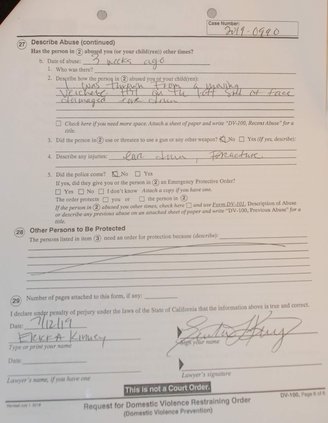

Brundin filed for a restraining order against Kinney on July 12 in Del Norte County — one day after Kinney filed for divorce in Humboldt County. In court documents, Brundin says that during an argument one night, Kinney threw her from a moving vehicle, pulled her hair, spat on her and hit her on the left side of her face, damaging her eardrum.

Request for domestic violence restraining order

“My body was hanging outside of the car and was touching the ground,” Brundin said. “He pulled me back in by my hair. I thought I was going to die.”

The petition was ultimately denied by Judge Robert Cochran on July 26. Cochran ruled that the case essentially has no connection to Del Norte County since the incidents in question all happened in Humboldt.

Brundin said she would ask herself why she put up with these types of attacks and said she eventually lost hope in herself. She described Kinney as an “alpha male” who is both physically and intellectually intimidating. She said he is a “typical abuser” who is “very good at what he does.”

“What he has told me before is that he intellectually gets to somebody and will knife them up on the inside and pull the knife out when he is ready,” Brundin said. “It is like a game of chess for him.”

Throughout her years with Kinney, Brundin said she heard about his treatment of women at work. She heard about rumors of sexual harassment and bullying.

###

A video profile of Kinney by the Earth Innovation Institute published last year.

Joe James, the current chairman for the tribe, worked directly across the hall from Lemke when she was employed in the office of self-governance. Lemke said James watched as Kinney would harass her, often to the point of tears. She said James knew what was going on, but had little power to stop him at the time. However, years later James pushed for Kinney to be the executive director of the tribe.

“Joe is no stranger to knowing how Javier treats women, and Joe is the one who pushed for him to become the executive director,” Lemke said. “Joe is the one who went out on a ledge to make that happen.”

Brundin said James also knew about her experiences with Kinney and that James was “one of the ones that wanted to sweep it under the rug.”

Brundin and Lemke both said that the formal complaints filed against Kinney were deleted once he became executive director. But verifying this information has proven to be difficult. Since the tribe operates under its own sovereignty, neither the California Public Records Act nor the Freedom of Information Act could compel the tribe to release any records.

“Tribes aren’t automatically under the purview of that federal law. So it would be a matter of looking at the specific Tribe’s laws/statues around FOIA, and then figuring out what is and isn’t subject to FOIA,” a representative from the American Civil Liberties Union wrote to the Outpost in an email.

But Brundin and Lemke aren’t the only ones to allege a cover-up by the tribe.

###

On November 6, a tribal council meeting was held to address the sudden resignation by Kinney.

While rumors abound, the Outpost could not verify the exact reason for Kinney’s sudden resignation and the subsequent outcry. But tribal members definitely have a theory. A tip by an anonymous source led the Outpost to Onna Joseph. She invited the Outpost to the tribal meeting on that Wednesday afternoon.

The meeting that day can be described as a #MeToo moment for the tribe. Eight women shared stories of past trauma done to them by men. A male tribal member also shared a story of sexual assault that happened to him at the age of 14.

Joseph was the second woman to address the tribal council on that foggy afternoon. She said she found the strength and courage to share her story because of the women that have historically spoke out against sexual abuse.

“I felt small and weak, but I know that I am far from small and weak,” Joseph said during the meeting.

She said that the incidents that led to the meeting that day should come as no surprise to the community. She called on the council to “do the right thing and quit the cover-ups.” Joseph went on to say that the council needs to do better to ensure a safe environment for the women who work for the tribe and for the tribe to take ownership of their actions.

“You’re not the Catholic Church who transfers dirty secrets to another parish,” Joseph said. “We should never move a predator to another department. Shame on you and this institution.”

Joseph called on the tribe to hire an independent investigator to look into the sexual harassment complaints. She said the staff and council lack the moral integrity “to document and enforce employment laws.”

Another woman who came forward asked the tribe to “take a really good look” at their personnel policies and alleged that “there has been some sweeping under the rug.”

“I’ve made complaints and I know there are complaints that are not in the files,”said Ruthie Maloney, a former employee of the tribe. “There has been some sweeping under the rug of some employees that have been harassed and have issues with supervisors. It looks like [the tribe] has been condoning this behavior and that is exactly how I felt.”

She went on to say that the work environment under Kinney was a main reason why there is a high turnover for those who work under him. She also said that these type of incidents are “something that has been going on for years” and called for a third party to review the complaints issued against other Yurok employees.

Celinda Gonzalez also addressed the council that afternoon. Gonzales said Yurok women have spoken out for quite a while about the issues surrounding Kinney. She asked what become of personal integrity in terms of how tribal employees conduct themselves. She also wondered what happened to the respect for Yurok women and questioned the favorable treatment given to Kinney.

“If this would have been anyone else, they would have been fired, not able to resign at their leisure,” Gonzalez said. “We are talking about a sexual misconduct. We are talking about a sexual predator.”

Gonzalez went on to say that the tribe should treat all employees the same and called for them to enforce sexual harassment policies more strictly. She also made a promise to other women.

“I am going to be a protector,” Gonzalez said. “I am going to be a warrior woman. Now is not the time to sit down and shut up; it is time to stand up. It is time to do better.”

A male tribal member who spoke up during the meeting called for the revocation of Kinney’s leadership position in ceremonial dances.

“High Dance family, no more,” Victor Knight said. “He cannot hold that position no more. Hereby revoke it.”

Kinney was in attendance that afternoon. After the eight women addressed the council he gave a brief statement. He said he was going through some personal issues and wanted to apologize for his actions.

“I want to apologize to Chairman James, to the council and to the community,” Kinney said. “I look forward to the cultural work and I look forward to the success of the tribe.”

When asked about the allegations against him, Kinney told the Outpost: “All personnel matters are confidential, and I hope you would respect that.”

###

The Wild Rivers Outpost’s Jessica Cejnar contributed to this report.

CLICK TO MANAGE