The obvious objection to the death penalty is that it can’t be undone. If a prisoner, jailed for life, is subsequently proved to be innocent through, for instance, DNA testing, he or she can be released. There’s no such reprieve for the dead.

In the US, the most notorious example of a reprieve occurred 13 years after five Black and Latino teenagers, the Central Park Five, were sentenced to jail terms in 1989 on the strength of their confessions to a brutal assault and rape. Within weeks of their interrogations, made without the presence of their attorneys, they all claimed to have been intimidated, lied to, and coerced by police into making false confessions. The trial and subsequent sentencing was muddied by full-page advertisements in four New York papers calling for the return of the death penalty, paid for by a real estate developer. Thirteen years later a convicted serial rapist and murderer, then serving a life sentence in New York State, confessed to the crime, which DNA tests corroborated. The verdicts were vacated in 2002, and 12 years later, the city settled with the five for $41 million.

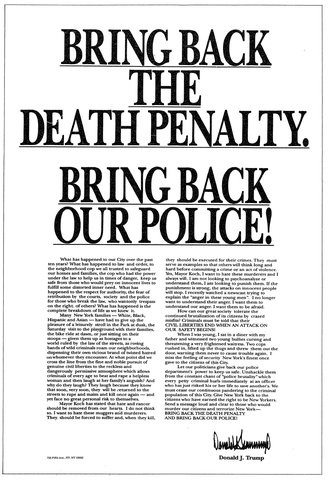

Donald Trump’s full-page ad placed in the New York Times, May 1, 1989, which, according to defense lawyers for the Central Park Five, biased their trial.

The developer, of course, was Donald Trump. Fortunately for everyone concerned, they weren’t executed (and New York formally abolished capital punishment in 2007), although he was unrepentant when asked recently by a reporter if he had any regrets about his role in the affair: “You have people on both sides of that, they admitted their guilt.” (When John McCain retracted his endorsement of Trump in 2016, he said that the candidate’s responses were “outrageous statements about the innocent men in the Central Park Five case.”)

I bring this up now because, as reported by The Washington Post, Trump’s Department of Justice executed more people (eight) in the five months starting in July 2020 than the DOJ did in the previous 50 years (three). Five more are scheduled to die before the new administration begins on January 20, including Dustin Higgs, a Black who didn’t actually fire the shots that killed three women in 1996. The last time a Federal execution took place during the transition of administrations was 100 years ago.

Exoneration of the Central Park Five is hardly unprecedented. According to the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Civil & Constitutional Rights (with updates by the Death Penalty Information Center), 172 people have been released from death row with evidence of their innocence since 1973. (Any older Brits reading this might remember the case that led to ending capital punishment in the UK, when Timothy Evans was executed for a murder later shown to have been committed by his landlord.)

The usual justification for retaining capital punishment is that it deters homicides. The facts say otherwise, and, in a survey, 88% of criminologists rejected the notion that the death penalty acts as a deterrent to murder. The South, for instance, with a murder rate of 6.0 per 100,000, accounts for 80% of all executions in this country; the Northeast, with half the South’s murder rate, had fewer than 0.5% of all executions.

You can read here why the death penalty is counter-productive, inhumane, costly, biased against Blacks, and opposed by most of us—61% according to a 2010 poll. If any of this moves you to action, please consider joining the seven million of us who belong to Amnesty International.

Aftermath

Trisha Meili, the jogger who was raped and nearly killed, somehow recovered (doctors at first thought she wouldn’t awake from the coma she was in), resumed jogging and went back to work as an investment banker. In 2003 she published a book, I Am the Central Park Jogger, and now works with victims of sexual assault through a program at the Mount Sinai Hospital. She still has bouts of memory loss.

Three of the defendants supported reform of New York State’s criminal justice practices by advocating methods to prevent false confessions and eyewitness misidentifications. According to Wikipedia, “Among their goals was required videotaping of interrogations by law enforcement; such a law was passed by the New York State legislature and went into effect on April 1, 2018.”

Another defendant, who now works as a speaker and justice reform activist, “donated $190,000 of his 2014 settlement to the chapter of the Innocence Project at the University of Colorado Law School, to aid other wrongfully convicted people to gain exoneration.”

CLICK TO MANAGE