The brain is a three-pound mass you can hold in your hand that can conceive of a universe a hundred billion years light years across.

— Marian Diamond

###

The fact that we’re alive today tells us that our brains are (more or less) optimized for whatever it took to survive and reproduce way back when, in conditions very different from our own. Here we are, living in a 21st century environment with brains which most recently evolved during the past million years—the last half of the Pleistocene epoch. Yet it’s pretty obvious—if you look around, read a newspaper, eat a typical “American” meal—that what worked long ago on the African savannah doesn’t necessarily work now, and from the point of view of our brains, they’re living in an alien world.

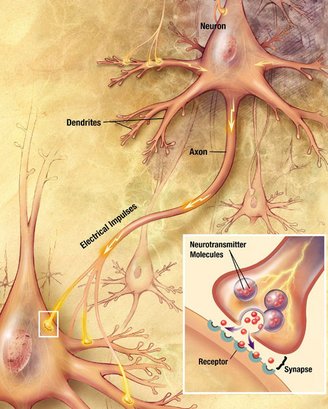

A human brain has 86 billion neurons (someone counted, apparently), each of which is connected to about 10,000 other neurons. (Looie496/National Institutes of Health. Public domain)

We can surmise, for instance, that those who survived—our foremothers and fathers—were the ones whose brains had the optimum mix of competition and cooperation to transmit their genes on to the next generation. That mix, though, may not be the best one for today’s national and international politics, since back then communities came in groupings of maybe a couple of hundred souls, most of whom would have been blood relatives. No wonder international peace is so elusive when you’re trying to deal with several million unrelated folks.

Then there are all those Pleistocene brain attributes that don’t quite translate into present-day advantages. Hear a hiss behind you? It’s OK, it’s just the espresso machine, not a snake. Or take happiness. A “happiness gene” would probably have a negative effect overall on genetic prowess, since (especially when food is scarce) anxiety would have played a lot better when it came to survival than contentment. So it’s hardly surprising today that happiness is fleeting. In addition: We cannot be other than irrational. It’s just the way we’re built. Survival a million years ago came from snap decisions, not from considered, thought-out ones.

More Pleistocene-evolved limitations:

- We cannot believe just anything: we are limited by the architecture of our brains.

- We cannot experience what our brains aren’t structured to experience. See in the infrared like snakes and frogs? Navigate by radar like bats? Smell like dogs? Forget it.

- We cannot understand everything: the wonder is that our Stone Age brains can make any sense at all of the universe as a whole. Quantum physics, consciousness, the origin of everything? They all may forever be beyond our capacity to understand. (But not, presumably, beyond the capacity of future AIs.)

- We’re stuck with the illusion of free will. Again, the architecture of our brains creates this illusion. (Why would someone who believes, “Everything is predetermined!” bother to run from danger?) We seem to act freely, of course, but, as I discussed recently, we don’t have a choice in that.

Meanwhile, the fact that our brains have us surviving, thriving even, in this alien world is testament to the adaptability of those 86,000,000,000 neurons. Yay brain!

CLICK TO MANAGE