“Audubon strongly supports properly sited wind power as a renewable energy source that helps reduce the threats posed to birds and people by climate change.” So begins a position paper on wind power by the National Audubon Society, the world’s oldest and largest bird conservation organization.

From Audubon’s point of view, reduction of fossil fuel emissions trumps death by turbine blades of comparatively few birds, writing, “…climate change has already affected half of the world’s species’ breeding, distribution, abundance, and survival rates … if climate change proceeds as expected, one in six species worldwide could face extinction.”

Now that the Terra-Gen proposal for 47 huge (nearly 600-foot high) wind turbines on Monument and Bear River Ridges has been voted down by our County supervisors, it’s worth taking a moment to review the realities of that decision. Had the Wiyot Tribe been fully involved from the start — given that the Bear River Ridge is an ancestral prayer site (Tsakiyuwit) — and had the planners persuaded the tribal elders that on balance, the project was good for the Earth, the vote may have gone the other way. But from the press reports, it looks like there was another important consideration leading to the negative votes: the potential impact to birds.

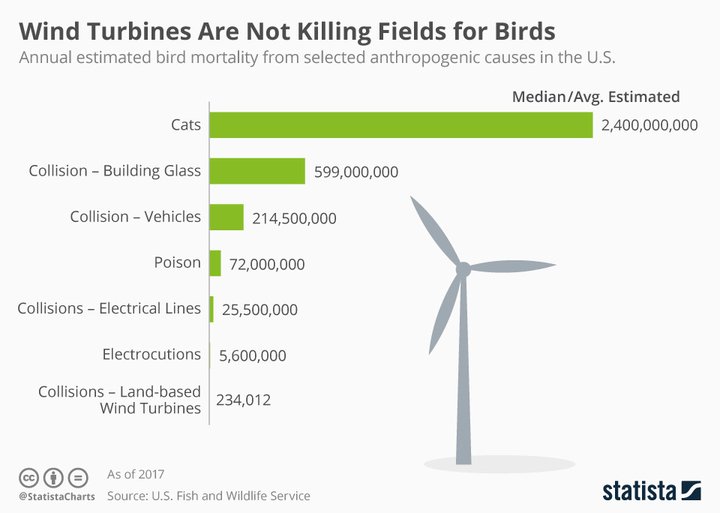

Statista, from US Fish and Wildlife data. Creative Commons license.

Putting aside emotional arguments, cats, both domesticated and feral, are by far the largest killers of birds in this country. The nation’s 100 million cats kill an estimated 2.4 billion birds annually. The killer-cat numbers come from a combined Smithsonian Institution and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2013 study. Here’s the link:

Currently about 50,000 wind turbines operate in the US, with a sixfold increase by 2050, potentially killing about 1.4 million birds per year. This means that cats kill nearly 2,000 times the projected 2050 wind turbine deaths. These numbers can be somewhat misleading, in that cats don’t kill raptors, their natural prey are songbirds (passerines), while those high slicing turbine blades can be lethal to the larger birds.

That’s why, for instance, at the Alta wind farm in Tehachapi, turbines in the path of California Condors are automatically shut down when the birds are detected (most wear radio transponders). Other experimental systems under consideration to deter birds include lights to make turbine blades visible at night, blaring sirens activated by proximity sensors and purple blades. (The latter supposedly attract fewer insects, and thus fewer songbirds.) Of course, what Audubon really means by “properly sited” is, away from bird migration and feeding areas.

California Condor with radio transponder, Pinnacles National Park. (Barry Evans)

But the bottom line for bird conservation is what the Audubon paper advocates: reduce emissions from coal- and oil-fired power plants. Wind power has the potential to supply 20 percent of the nation’s electricity, according to the DOE. (The Terra-Gen’s project would have supplied about half Humboldt’s electricity demand.) I fervently hope a less contentious wind generating site can be found here in Humboldt, and soon. And — word to the wise — that whoever proposes it gets our native tribes on board from the start.

CLICK TO MANAGE