That’s a line from Ted Hughes’ spirited translation of Aeschylus’ Oresteia, as spoken by Cassandra, the Trojan princess both blessed and cursed by Apollo: blessed with the gift of prophecy, cursed because no one believes her.

The Oresteia, written about 460 BC, is probably the earliest work to explore the issue of free will. It was a conundrum the ancient Greeks pondered and stewed over as much as modern-day philosophers—any of us, really, who has asked ourselves how our decisions in life are actually made. The Oresteia features so many deaths and so much justification, with everyone appealing to fate, to duty, to the gods.

- Agamemnon had to sacrifice his daughter, or the Greek fleet wouldn’t have gotten a west wind to sail to Troy.

- Clytemnestra had to kill her husband Agamemnon to avenge her daughter’s murder.

- Orestes had to kill his mom Clytemnestra to avenge his dad, since he couldn’t disobey Apollo’s order.

- The Furies had to torture Orestes near to death for murdering his mother, since this was their Fate-bound role.

The Furies (spirits of retribution) pursue Orestes after he had avenged the death of his father by murdering his mother. (William-Adolphe Bouguereau, 1862). Public domain.

The question Aeschylus keeps throwing at his audience (then and now) is this: Could any of them have done otherwise? Could Agamemnon have said, “Y’know guys, my daughter’s life is a damn sight more important than sailing off to Troy to bring my sister-in-law (Helen) back!” Could Clytemnestra have done otherwise in response to her daughter being sacrificed? What about Orestes: “Hey Apollo, mom killed dad because dad killed my sister, duh. Why should I do your bidding?” In other words, did they have free will? Or were they all fated to follow Cassandra’s gloomy dictum, What must happen has already happened?

I keep returning to the paradox of free will, because I see it as a sort of back-door approach to consciousness and self—and it’s much more accessible than the usual high-level approaches. That is, “self” is such a woolly concept, a metaphor for…what? Mind? (Which is a metaphor for…self?) Whereas I think most of us can agree that free will is a real issue, one we can get our teeth into, since it goes to the heart of life and living. For instance, if we don’t have conscious free will, where does that leave our justice system? (“Sure I shot him, your honor, but I didn’t have a choice!”)

Suppose someone proves, beyond all doubt, that you don’t actually have a “self”—there’s no little person inside of you—it’s all an illusion, you’re deluded, and now you (!) have seen the light. And you say, “So what?” Me, I still hurt when I read about injustice in the Middle East. I still feel pain when I cut myself. I still feel good when I laugh. Nothing changes, self or no-self.

This is an intensely personal issue. I had a profound awareness 45 years ago that left me with the belief that I am, indeed, on “automatic.” I was participating in a day of self-massage and meditation when a friend asked me from across the room if I was OK. “I’m fine, Mick, thanks,” I replied. Those were the words that came out of my mouth, but what I clearly “saw” was a vast laboratory filled with computers, with those words coming straight off an old reel-to-reel tape recorder, completely automatically. “I” was merely the observer, not the decision maker. It was all pre-programmed. That incident changed my life, paradoxically filling me with gratitude that has never left.

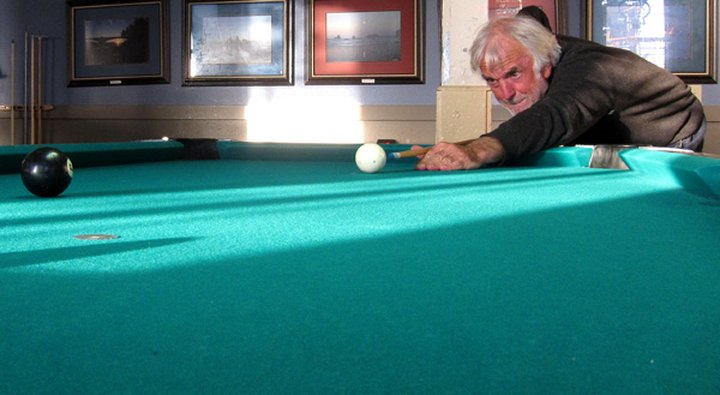

Are you the player or the ball on the great pool table of life? (Jacob Pounds)

While I believe that self and free will

are two sides of the same coin, free will seems to be the more

accessible. It’s the issue that I can discuss while having at least

some idea of what I mean.

Hello? Anyone out there?

CLICK TO MANAGE