Tamara Myers can hardly put the importance of the Freshwater Community Guild into words.

For one, there’s its relationship with Garfield School, which dates back 137 years, by Myers’ estimate. Across a small lane and parking lot from one another, the hall and school, both bright red, might easily pass as the same entity to any passerby unfamiliar with Freshwater. It’s where Myers tested out her acting chops in a school production of Oliver Twist, and where she scribbled her name on a wall backstage alongside dozens of other childrens’ graffiti, chronicling back to the early 1900s.

Kiddos have been graffitiing backstage at Freshwater Community Guild since the 1910s. | Photos by Jacquelyn Opalach

And then there’s the fact that the hall is the only public space Freshwater has for neighbors to connect. Thousands have do-si-doed on the hall’s wood floors over decades of dances. Every Halloween, the hall is a warm, festive refuge for families taking a break from Freshwater’s epic trick-or-treating scene. And for generations, folks have known that missing the monthly pancake breakfast means missing the latest local gossip, Myers’ mother, Mary Myers, who has been the organization’s secretary for more than 30 years, told the Outpost.

And so for Myers, it’s hard to talk about the Freshwater community without talking about the hall.

“I just can’t imagine it not being there,” she told the Outpost. “It’s very much a part of my reality, my world.”

But Freshwater Community Guild — formerly known as the Freshwater Grange — might close its doors.

Until several years ago, Freshwater Community Guild was part of the Grange, a nationwide organization founded in 1867 to advocate for farmers and rural communities. The California State Grange chapter wants Freshwater’s hall to become a Grange once again, and they want its volunteers to become Grange members, or Grangers.

But locals don’t want to. So the State Grange sued for their property.

The same conflict has risen at community halls across the state, and Freshwater Community Guild, as well as three other halls in Humboldt — Bayside Community Hall, Van Duzen River Guild and Fieldbrook Community Hall — continue to resist the Grange.

They resist it because the California Grange didn’t buy and hasn’t maintained the properties — local communities did. They resist it because they believe the Grange no longer represents their communities’ interests, and because it honors traditions and rituals that locals find off-putting. One hall leader said the organization feels cultish.

They resist it because they don’t want to be Grangers, but they also don’t want to lose their halls.

If these halls are successful in beating back the Grange, it would be a first. Over the last few years, dozens of local California halls have resisted the Grange. Each was independently sued and fought isolated from their neighbors. The few California renegades that remain unswallowed by the Grange — half of which are in Humboldt County — are putting forward a question untested by California courts: Whether California property law and corporate rights trump the dated, amendable rules of a fraternal organization.

The Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry — referred to here as a singular organization, although it is composed of national, state, regional and local chapters — argues that their intention is to retain these halls as local grange chapters for the benefit of small communities. But the local volunteers who run them worry that if the Grange is successful in seizing the properties, its leaders will fail to maintain them from afar, and some of Humboldt’s tightest-knit communities will lose the gathering places they’ve loved for generations.

Freshwater Community Guild

A decades-old clash

The lawsuits are the result of a conflict that began years ago between the state and national grange chapters. Due to what Myers summed up as “personality conflicts” between leaders of each chapter, the National Grange revoked the California State Grange’s charter, intending to deactivate the state organization.

But instead, the California State Grange decided to operate as an entity separate from the National Grange. Its president, Bob McFarland, renamed the California organization the California Guild (because of a trademark lawsuit from the National Grange), and most local halls followed suit over the next few years by changing their own names from “grange” to “guild” or “community hall.”

The number of Grange-affiliated halls dropped from about 180 to 26, according to Lillian Booth, secretary of the California State Grange.

Freshwater Community Guild’s hall

At the request of those 26, the National Grange rechartered the California State Grange with new leadership. At that point, there was both a California State Grange and a California Guild, but the rechartered State Grange soon sued the Guild for its property and assets and won.

“When National Grange revoked the charter of the State Grange, they did not revoke any of the charters of the local granges,” Booth told the Outpost. “All those charters stayed in effect, until they took some bad advice, which was to change the name of their organization, change their corporation and change the deeds on the property.” According to rules of the organization, taking those actions was illegal.

And so because halls made those changes, the State Grange revoked dozens of local charters from 2018-2020 and asked halls to turn their properties over.

“When people say we left the Grange — no, actually, that’s not what happened,” Myers said. “We got kicked out. They revoked our charter.”

The State Grange followed up with lawsuits in pursuit of halls’ properties soon after revoking their charters.

A cozy corner of Freshwater’s hall.

“The lawsuits unfortunately had to start because that was the only way to retain the property, and, hopefully, the members who wanted to come back to the Grange,” Booth said. “It breaks my heart we had to go down this road.”

Over the years, the conflict has been hashed out in more detail by other publications around California, including the North Coast Journal. The State Grange also has a summary of events posted on its website.

Different halls are in different spots of their lawsuit timelines, but so far nearly every case has been resolved through summary judgment, in which the judge decides the legal questions presented without a trial. The speed of that resolution process has been upsetting to local halls, who feel their cases should warrant a trial. The Grange has won almost every case, but an appeal of that decision could lead to a trial and reverse the outcome.

Today, about 100 of 180 original halls have returned to the Grange, Booth said. Many returned as the result of a lawsuit. Others did so to avoid one. “Many of them said that they were just glad to be back doing what they had already been doing in the community,” Booth said.

As of early August, about 10 halls were still battling lawsuits, although that number is decreasing as more halls agree to rejoin the Grange. About 20 halls are empty and in a custodial status, meaning the Grange is actively trying to find a membership for them. A few of the 50-some granges unaccounted for in the original 180 may have only ever existed on paper, Booth said. Others were sold or demolished by the State Grange and no longer exist.

An old backstage painting at Freshwater Community Guild.

Carolyn Jones, president of the Bayside Community Hall, believes that the State Grange is operating in this heavy-handed manner because few local halls in California have any attachment to the Grange name.

“I’m sure they would disagree with this, but I believe that they are feeling very insecure about attracting members to the organization in its own right,” she said. “And so now, the way that they have attracted the membership they currently have is by essentially holding these halls hostage.

“There are many halls, I believe, that would not be grange chapters if they didn’t think they had to be in order to maintain control of their hall.”

Property law on the Grange’s terms

Founded in 1867, the Grange system is a fraternal, hierarchical organization spanning from national, to state, to regional and local control. Each pillar of the organization is chartered by the national chapter and is meant to follow its own sets of rules, or bylaws, as well state and national bylaws. The National Grange’s Digest of Laws has been amended a number of times since the organization’s genesis.

One of those National bylaws — 4.12.1 — states that if a local, regional or state grange ever loses its charter, it becomes an “inactive grange,” and its hall and assets — bank accounts, business interests, all property — become the responsibility of the grange level above it. While in that “custodial” status, the State Grange attempts to reorganize a local grange chapter for the hall. In other words: Once a part of the Grange, always a part of the Grange.

Because this bylaw didn’t exist when some halls were chartered, and because the deeds of these halls specify local ownership — rather than State or National Grange ownership — local hall leaders don’t see how the Grange’s legal argument holds water, marking the root of this conflict.

Issued by the National organization, “the charter is essentially the birth certificate of a grange,” Booth said. “It goes from one generation to the next, and that’s how it’s been able to be a viable organization for over 150 years now.”

The leading volunteers of Humboldt’s local halls disagree.

“Until the National is gone, as far as they’re concerned, no piece of property that we own is actually ours, which would appear to be in violation or in contravention of certain parts of California law,” Jones said.

“The real legal issue here, I think, is this one-page charter, and that’s what all of us is dependent on — a single page charter with a nice little seal in the corner, and not a whole lot of writing on it — that single page document and its power is up against all of California law.”

Fieldbrook Community Hall

‘Not a single dollar donated’

Equipped with kitchens, stages and often yards, Humboldt’s four renegade community halls are used for private and public events like weddings, dances and pancake breakfasts. By providing an affordable rental space or by hosting fundraisers, each hall also helps local entities like schools, emergency response teams and nonprofits.

All were built using local funds and local labor, and have since been maintained — one of them for more than a century, and others for nearly that long — by local volunteers. Some were built specifically for the grange chapters they held; others predated their grange.

Hall members might feel differently about the lawsuit if the Grange had a history of helping with disasters, repairs and upkeep, but locally, at least, it doesn’t. In Bayside alone, volunteers have raised and completed $400,000 worth of renovations for their hall over the last three years.

“They’re not willing to invest,” said one member of the Freshwater Community Guild. “Not a single dollar donated.”

When a 1964 flood wiped out the Redwood Grange — now the Redcrest Community Center, which this week opted to rejoin the Grange — and its nearby communities, it was left up to a few local Grangers to rebuild. Pacific Lumber Company donated a lot, and using local funds and labor, volunteers rebuilt without help from the State and National Granges.

More recently, when the Van Duzen River Guild — formerly the Van Duzen River Grange — needed a new roof in the 1990s, it applied for a loan from the California State Grange, which ran a credit check and denied their request. It took donations and volunteer help from Alves Inc and the community to get the job done.

“That left a really really bad taste in the mouth of the community,” said George Warner, president of the Van Duzen River Guild. “They were really incensed by the fact that nobody would help us.”

Fieldbrook Hall’s hall

That would be handled differently today, Booth said. “Things are not the same now as they were then,” she said, adding that communication is a two-way street, and that grange halls need to let the state know when they need help. That help would be in the form of a loan, via the Grange’s loan fund, Booth said.

But animosity is not what’s fueling these halls’ efforts to fight their lawsuits. They’re more concerned about what it would mean for their communities, and the partnerships they’ve built, if the Grange wins.

All four halls have developed important relationships with nearby schools.

For instance, Freshwater Community Guild does more than just allowing Garfield School to use their hall for performances and graduations. The hall leases its parking lot to Garfield School for one dollar a year, and the hall once raised $10,000 to fund speed humps on the road nearby.

“If we were to close for any reason, it would have such a detrimental impact on Garfield School,” Myers said. “The amount of kids that could be enrolled would go down.”

In Hydesville, Cuddeback School has been hosting graduations at the Van Duzen River Guild for decades. “My mom walked across that stage in 1943 in the middle of World War II. Graduated eighth grade,” said Warner, president of the hall. “It’s part of us. Part of our family, part of our community.”

Similarly, when Fieldbrook School was being rebuilt, lower grades held classes in Fieldbrook Community Hall.

And Bayside Community Hall does the same.

A corner of Fieldbrook Community Hall

“We have a school right next door. They use our yard, they use our hall for performances and meetings and things like that in exchange for maintenance work on the property,” Jones said. “The hall has morphed, I think, like all of ours have, into what the local community finds useful and helpful and valuable. And it doesn’t appear to be the kind of one-size-all that the Grange wants to sell us.”

Led by longtime member Margie Plant, Redcrest Community Center in Southern Humboldt resisted the Grange alongside the other four halls for years. Particularly important to this hall was a partnership with the Redcrest Volunteer Fire Department, which recently began construction of a fire truck security building on the hall’s property. With direct access to the freeway, the fire department deemed the property ideal for immediate emergency access, and so in 2012, when the hall was still a grange, hall volunteers agreed to the building’s construction and secured permission from then-State President Bob McFarland to do so. Construction commenced shortly after the hall received notice of their lawsuit.

To discuss potentially rejoining the Grange, Redcrest Community Center met with four Grange representatives, including Booth and state president Kent Westwood, earlier this month. At that meeting, the Grange wouldn’t promise that they would allow completion of the building, claiming they hadn’t seen the paperwork.

Unfinished, the fate of this Redcrest Volunteer Fire Station security building is in the State Grange’s hands.

On Monday seven members of the hall voted to rejoin the Grange, Margie Plant, the hall’s former president, told the Outpost. Attendance at that meeting, which had only the vote on its agenda, was poor, Plant said, adding that it seemed like the members not in attendance felt put off and disheartened by their prior meeting with the State Grange.

Deflated, Plant resigned following the vote. “I don’t want anything to do with the Grange organization,” she told the Outpost.

It’s unclear whether the State Grange will allow completion of the fire truck security building, or whether they’ll charge rent if it is completed. The remaining members are hopeful they’ll come to an agreement for its completion in a settlement with the Grange, Plant said, but nothing is guaranteed.

“It is difficult to fathom that when the community donates land, builds the building, and maintains it consistently over all these years, that a large corporation could suddenly lay claim to it,” Rowetta Miller, executive chair of Fieldbrook Community Hall, told the Outpost. “This corporate land grab would be an obvious injustice.”

Redcrest Community Center will soon again be Redwood Grange.

No comfortable option

The lawsuits would disappear if halls opted to rejoin the Grange, which is the organization’s goal. Members would apply to become Grangers, take an oath to follow the Grange’s bylaws and pay dues of $30 per year to the organization.

Walking away from their halls would have the same outcome as losing the lawsuit: surrendering the properties to the Grange, which would hold the halls in a custodial status — temporarily claiming jurisdiction over the property and assets — while attempting to reorganize chapters for each building in no less than seven years. To do that, the Grange would host an open house at the hall and invite locals to learn about the organization.

Once there are 13 or more members — with at least four men and four women, according to bylaws — the charter is restored and the State Grange steps out, Booth said. “The good work that they have been doing will continue. But unfortunately, they need to continue as a grange, not as a community hall or as a guild. They need to come back into the Grange, and we welcome everyone back into the Grange.”

Locals doubt the Grange will find enough folks willing to join, but Booth told the Outpost that it hasn’t been a problem in other parts of the state, and she doubts it would be a problem here. In Redcrest, for instance, seven current members will become Grangers. If the Grange were to win Fieldbrook, though, none of the hall’s existing 25-30 members are willing to join the organization, Miller said.

In the interim, the State Grange would attempt to meet existing obligations of these halls, like weddings, dances, or other events renters have booked in the coming months. They would also be responsible for maintaining the hall during that time. Booth said that the Grange usually tries to find a local willing to volunteer to do that work.

If a new chapter isn’t formed within seven years, the State Grange can sell the property. Halls are only sold if in irreversible disrepair, Booth told the Outpost, and 85 percent of the profits go to the Grange loan fund — which finances repairs for grange halls — while the other 15 percent goes to the State Grange general fund.

Appealing lost cases is a gamble. To maintain local control during their appeals, which will likely take more than two years, halls would need to post bond, and bonds on halls around California have ranged from $50,000 to more than $200,000.

The State Grange will take control of halls that don’t post bond during their appeal.

If a hall wins its appeal, the case will go to trial locally, and the ruling of that trial will finally determine who owns the hall.

“Those of us who have insurance, we’re able to fight, but we’re losing,” Jones said. “Almost every motion for summary judgment has been granted, giving the Grange hall property without a trial.”

Three of Humboldt’s halls have been able to fight because they have liability insurance to fund their legal defenses. Fieldbrook Community Hall doesn’t have insurance because they thought they had a valuable edge to their case: a clause in their grange chapter’s original deed, which specifies that if the Grange were to ever dissolve, the title to the property would revert back to the Fieldbrook Community Club, the hall’s original owners.

“This makes our situation unique and a bit different than other halls. We thought we were safe as our property was secured with a legally recorded agreement,” Miller, the hall’s executive chair, told the Outpost. “They sued us anyway. Because we do not have directors and officers insurance, we’ve had to limit our legal representation to what we can afford.”

Jones thinks she’s worked out a reasonable compromise to this conflict that would satisfy the goals of each side. She wants the Grange to institute a new type of membership, and wrote a petition to garner support for the idea, which has so far collected 218 signatures:

We petition the California State Grange to declare that all halls are owned by their local communities. We petition for development of a membership option that allows a former grange to become a non-voting affiliate, to pay dues and provide a meeting place for a chartered local chapter, but to otherwise function as an autonomous organization. We believe that this would provide the best opportunity for success for both local halls and the grange organization.

Booth declined to comment about the idea, claiming she hadn’t been made aware of the compromise.

A former grange in Shasta County — Palo Cedro Community Guild — is ahead of all the others. Determining their case warranted a trial, the Shasta County judge denied the motion for summary judgment requested by the Grange. Their case will go to trial in September.

“If they win, that would be huge,” Jones said. “If they lose it, that’s it.”

Bayside Community Hall

Why not join the Grange?

Some locals deep in lawsuits wholeheartedly believe the Grange served its purpose well in these communities for a long time and respect the organization’s mission, and there are few other halls in Humboldt County successfully operating as granges. But today, aside from the lawsuit fiasco, current volunteers of these four halls largely aren’t interested in joining the Grange because they don’t personally identify with its values.

Since its post-Civil War establishment in 1867, the National Grange has marketed itself as a bipartisan advocacy group for rural farmers and communities. Local halls are meant to drive that advocacy.

“We don’t take our partisanship into the Grange. We support issues, not candidates. We advocate on so many different levels. And if that’s not for you, then we have the other parts of the Grange, which are educational,” Booth told the Outpost.

Rather than attracting Arcata residents, Jones thinks the advocacy element is probably off-putting for most, given that the city is not so rural anymore.

Bayside Community Hall has renovated their entire kitchen since 2018.

“We have a really mixed community, way more mixed than appears to be the demographic of the Grange. They say: ‘We’re rural, we’re agricultural, we can advocate for you!’ Well, my point is that almost any position that they take is probably gonna piss off half of our community,” Jones said. “We want to be there for the entire community.”

As a fraternal organization, the Grange must offer something of tangible value to its members. At one time, that thing was super-affordable insurance, which, some say, is what encouraged folks to join their local grange back in the day.

“The Grange insurance was cheap. I can’t think of hardly anybody that I’ve talked to over the years that, at one point, their family or somebody in their family hadn’t had Grange insurance,” Warner said. “We had almost 400 members in the late 80s, early 90s because to get insurance, you had to be a member.”

But years ago, before this conflict even began, the insurance provider, Grange Insurance Association, took their company public. And now, as far as local hall leaders can tell, there’s not much of anything tangible the Grange is offering up.

Booth didn’t deny it and pointed to the intensity of the split and its consequential loss of membership. “Because the split happened in 2012 — this is nine years ago — and when you lose that force of membership behind getting tangible benefits, it takes time to rebuild that,” Booth said. “You have to have the membership behind it, you know, the numbers. It has to make sense for the companies,” she said, adding that the Grange is actively seeking out new benefits.

Bayside Community Hall’s hall

She mentioned a potential partnership with AmeriGas, a propane company, which currently offers a discount to grange members in certain regions of California. “We’re looking at talking to them about doing that on a statewide basis,” she said. “So, yes, it applies mostly to rural communities that have propane, but it’s still a tangible benefit.”

Beyond lack of interest in the Grange’s basic offerings and benefits, members are wary of the organization’s bylaws and practices. For instance, new Grangers must be unanimously voted in by the existing local membership.

“It has the inherent potential for being a closed organization. We may all run ours in such a way that anybody who fills out the form, we want in.” Jones said, but “it is very easy for a grange to deny someone membership or to vote someone out by their rules.”

And their rules are extensive. Local granges must use a state-developed template to create a set of bylaws that cannot conflict with the bylaws of the state and national chapters. These bylaws run to more than 100 pages long, and in theory local granges are supposed to follow to the letter.

“How many people are actually going to go and really learn about what [they’re joining]?” Jones wondered. “They’re joining to be part of their community, right? Not to pledge faithful allegiance to a complex set of national rules that have changed over the years. And a lot of us don’t even really know what those rules looked like when our halls were chartered, which should be a really important issue, one would think.”

Locals claim that in the past, bylaw enforcement seemed to ebb and flow.

“They used to send people around to our meetings to intimidate us and threaten [us to] follow their rules,” Warner said. “It didn’t sit well.”

Nowadays, though, the bylaws are apparently no big thing. Local hall volunteers say that other grange halls have encouraged them to just rejoin, claiming that as long as member dues are paid, the State Grange gives little attention to whether local granges are actually following bylaws.

“That also makes me very uncomfortable: The idea of joining something, and saying you’ll follow the rules, and then just ignoring the rules until such time as the state or national organization decides that they want to call on you for not obeying the rules,” Jones said. “I mean, they can do that at any time.”

Inside Bayside

That’s a rumor, Booth said later in an interview, the Grange mentors local halls and keeps an eye out. “If there’s a problem with the bylaws, then we help them understand the bylaws,” she said.

People are also perplexed by the organization’s traditional practices, and are worried about joining something with antiquated beliefs. The Grange has a history of honoring farming-themed rituals, which state president Kent Westwood told the Outpost are basically little performances that local halls are not required to practice. Jones, who in her life has attended just one formal grange meeting, said it felt cultish.

For instance, the State Grange constitution outlines that members of local granges work their way through four degree ranks, which each bear different responsibilities. Each degree is represented by two gendered titles, like the First Degree’s “Laborers” and “Maids,” for example. That type of thing is just a part of Grange history, Westwood said, and most halls just ignore it nowadays.

Booth implied that the only required practice is the opening ceremony, which takes three minutes.

That said, the Grange continues to honor religious practices. Here are a couple of bylaws from the National organization’s Digest of Laws, from the Code of the Junior Grange and Code of Ritual, Degrees and Regalia, respectively:

“The Chaplain shall encourage reverence to God through the opening prayer. The emblem of the office is the Bible, the book in which all should look for guidance.” And: “All Granges shall have the Bible open on the altar and the flag of the United States of America properly displayed in the Grange meeting room.”

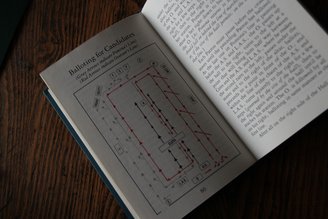

Grange ritual diagram outlining where certain members are to walk and stand during a traditional ceremony.

Touting the organization’s bylaw resolution process — which is meant to be driven by local granges — Booth said the California State Grange is interested in amending that second rule to allow any holy text, and said the State Grange has brought that resolution to the National Grange convention three years in a row now and will continue to do so until that bylaw is more inclusive.

“If you don’t like the rules, there is a system to change them,” Booth said in an interview. “But until you do that, granges have to follow the rules.”

Today, Grange membership is declining. In its heyday, all 50 states had state and local charters; now only 34 do. Before the lawsuits between the state and national organizations began, California membership was at 10,000; now it is half that. Since 2000, Humboldt County and Del Norte have lost more than a dozen granges, Jones said.

Few locals are jazzed about joining the Grange, but some are willing to do it to maintain control of their hall. A recent poll of 55 Bayside Community Hall members, published in a regular Mad River Union column written by Jones, found that more than half will become less involved with the hall if it returns to the Grange. Seven people would be highly interested and ten somewhat interested in joining the Grange, the poll found, but 78 percent of respondents agreed that the hall should not voluntarily return to the Grange.

Van Duzen River Guild

Bleak and less bleak outcomes

If the Grange wins, these halls, their assets and accounts would become the Grange’s responsibility, which would attempt to recharter a new grange chapter in these buildings within the next seven years. In the meantime, though, it’s unclear whether partnerships — like those with the schools — would survive the transition, and whether the Grange would manage to honor upcoming events scheduled at the halls.

“What’s gonna happen to all of those? Are they actually going to come in and unlock the doors, and clean bathrooms between events, and clean up the yard, and pay the bills and make sure that the trash is taken out? ” Jones said. “Are they gonna do all that stuff?”

Van Duzen River Guild’s hall

The State Grange says it will.

Some hall volunteers, who have been trying to gauge Grange interest in their communities without much luck, worry their halls will sit, shuttered, until being sold due to disrepair in seven years. That’s a huge concern of Myers’, who said Freshwater’s hall needs pretty consistent attention to keep standing.

Booth seriously doubts the Grange will lose. “We have not lost any of these. And I don’t anticipate us losing any of them, either,” she said. “The loss is the fact that we aren’t able to sit down and talk.”

The fighting hall volunteers are exhausted.

“[I’m feeling] disenchanted but hopeful,” said Warner of the Van Duzen River Guild.

“Me personally? I’m not terribly hopeful,” Jones said. “I don’t think there’s any justice in what’s going on at all. It doesn’t make any sense to me … Our ruling, to give away, you know, all of our property, was a page and a half long. It did not address any of the legal arguments made by our attorneys.”

Myers is thinking along the same lines. “I am incensed that there has not been a day in court, not at the state level. It’s all been motions for summary judgment,” she said. “I am worried. I am worried about our community. That’s really what keeps me up at night. I am worried the school will not have an asset. Every day.”

CLICK TO MANAGE