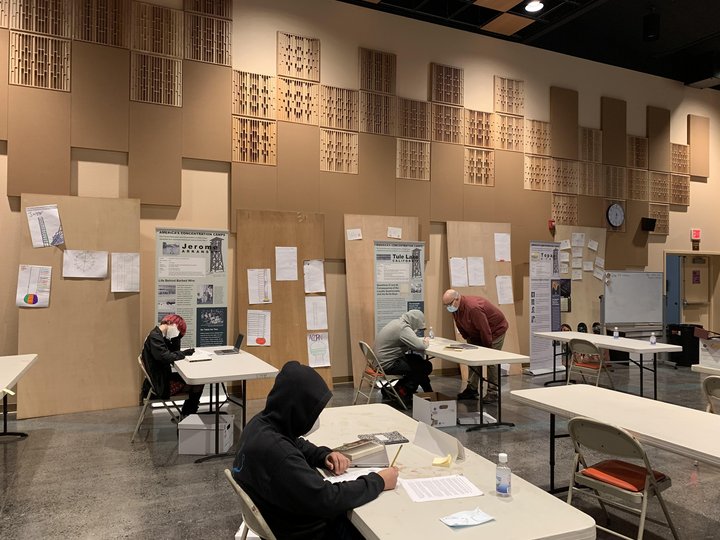

Inside the Acorn Project classroom. Photo: NHUHSD.

###

To ensure that learning through COVID doesn’t knock struggling freshmen off track, the Northern Humboldt Union High School District has introduced a new program, called the Acorn Project, to help students make up units lost during their first semester of high school.

As they near one year taught almost entirely virtually, the district’s three comprehensive high schools — Arcata High, McKinleyville High and Six Rivers Charter High — saw an increase in the number of students earning at least one D or F during the 2020 fall semester compared to pandemic-free semesters past.

“We’ve got a number of kids who, if it was not for COVID, they would have been doing fine,” Jack Bareilles, NoHum’s grants and evaluations administrator, career and technical education administrator, and a main visionary of the Acorn Project, told the Outpost recently. “It’s just, COVID has been hard. Stay-at-home has been hard on everybody, and some of our children have really just struggled.”

Younger students have struggled more than older ones — 57.8 percent of freshmen versus 23.3 percent of seniors ended up with at least one D or F on their transcripts this fall. By comparison, during the fall 2019 semester, 36.2 percent of freshmen versus 22.6 percent of seniors were on that list.

A different, and perhaps better, way to understand the challenge students are facing right now is to compare how the grades of a specific group have changed pre- and post-lockdown. The 36.2 percent of freshmen who earned at least one D or F in 2019 have jumped to 42.9 percent as those children became pandemic-era sophomores. By contrast, fewer students from fall’s 2019 junior class are now on the list as seniors; 26.4 percent has dropped to 23.3 percent. Some students are academically doing better with distance learning.

NoHum is not alone; schools everywhere are reporting double and triple the F’s they typically see under normal, non-pandemic circumstances. Districts are on their own when it comes to finding a solution.

The long-term impacts of COVID-driven academic setbacks have been on the mind of Greg Cornelison, the Acorn Project’s lead teacher, since before he was hired a couple months ago. If students flunk their freshman year because of COVID, how will that impact the rest of their high school experience, and beyond? He said he worried “we would lose a big chunk of this generation” to dropping out or depression.

After moving to Humboldt from Merced in August 2019, Cornelison, with years of full-time teaching behind him, worked as a substitute teacher around the county. He ended up teaching tech essentials at NoHum as a long-term sub last semester. When the Acorn position opened, “I jumped at the opportunity to, you know, be a part of a solution. I don’t know if it’s the solution, but it’s a solution, and it seems to be working,” said Cornelison.

That solution, the Acorn Project, is an emergency intervention classroom currently supporting 20 Arcata and McKinleyville freshmen who have been unable to keep up in a virtual format and have fallen significantly behind in units. The goal is to help those students make up the credits they lost last semester, which would set them on track to enter tenth grade and eventually graduate alongside the rest of their class from one of the district’s comprehensive high schools. The program launched virtually at the beginning of January, but they started bringing the students on campus a few weeks ago.

“It’s going great,” Cornelison said of the program. “The kids are just so happy to be back with other students, and having some social contact.”

Bareilles said the program is averaging a 90 percent attendance rate. “They’re showing up, they’re happy to be there. I mean, my gosh, after being at home during COVID, it’s a joy to come to school.”

The classroom is set up in compliance with COVID safety measures. Large, single-person folding tables are spread several feet apart across the auditorium in Arcata High’s Fine Arts Building, and all students and staff are supplied with KN95 masks. The school day runs from 8:30 to 12:30, with a break in the middle and breakfast and lunch provided on either side. The curriculum covers English, math, global life science, and health and tech.

Wednesdays at the Acorn Project are reserved for field trips and community service projects. For instance, the class might go to the Arcata marsh or other outdoor areas where students could do some kind of science lab.

“I’m hoping to work with Yurok and/or Hoopa Valley tribal fisheries, and get the kids up on the river and be able to work with the fisheries’ biologists,” Bareilles said. “My hope is that they get their science credits, or their science experiences, by being out in the field and working and learning from your actual practitioners.”

Students will also take a college and career success class at College of the Redwoods, make a four-year plan, and have access to academic and crisis counselors. Beyond helping them catch up, the goal is to help these students feel prepared and equipped to take on their sophomore year, when they’ll rejoin the rest of their class with credit recovery behind them.

“Everyone’s supporting these kids like crazy. It’s just awesome to see, and they’re responding,” Cornelison said. “I have not heard one say ‘This sucks, I want to go back to Zoom.’ You know, they’re just happy to be there, even though they’re doing school.”

The Arcata Acorn classroom is at capacity, and the district plans to open a second classroom at McKinleyville High later this month, which will serve 12 more students.

If not for the program, these students would need to take three sessions of summer school to catch up. Otherwise, they would likely need to transfer to one of the district’s continuation schools — Mad River or Pacific Coast — which help students 16 and older earn back credits needed to graduate but do not assign grades. “Those are all really, really good programs, who really, really care for the kids,” Barellis said. But transferring does mean that students are left with little opportunity to participate in the electives and extracurriculars available at NoHum’s comprehensive schools, like the Arcata Arts Institute, ArMack Orchestra, culinary classes, wood and metal shop, or other career and technical education opportunities (all of which are all currently available to students during COVID). “It’s not that the teachers aren’t caring and compassionate and wonderful. But when you only get a kid for a few hours a day, you have to limit what you can do with them,” Bareilles said. (In California, continuation schools require students to spend a minimum of 15 hours per week at school.)

Without access to more niche educational opportunities, Bareilles worries, students might be missing out on the resources to develop job skills or discover a potential career path.

Students shouldn’t miss out on that because of a pandemic, which is why the Acorn Project is arriving now. But freshmen who fall behind in units under normal circumstances shouldn’t miss out either, Bareilles says. And the problem existed before COVID — it’s just intensified with distance learning.

For instance, 30 percent of the class of 2019, which entered the district in 2015, didn’t graduate from one of NoHum’s comprehensive high schools. Because of falling behind in units, those students had to relocate to and graduate from continuation schools or other alternative programs outside of the district, Bareilles said, adding that “we do a really good job of keeping kids in high school.”

NoHum has been aware for a long time that “our schools have an attrition problem with kids who start ninth grade and don’t make it to 11th grade in the comprehensive high schools,” Bareilles said. In contrast to the continuation schools, Acorn is an early intervention program that will allow students to rejoin their class at a comprehensive school after one semester, rather than separating them down the road and permanently.

At a December board meeting, Bareilles shared that 30 percent statistic, and Board Member Cedric Aaron asked if there is a way the district might measure why students are choosing to switch schools. Aaron referenced a recent equity roundtable discussion — where speakers shared that they left high school because of discrimination, bias, microaggrassions and macroaggressions — and wondered whether there might sometimes be more to deciding to leave than just not understanding the academics.

Bareilles assured Arron that students change programs almost always because they lack units, but why they lack units is harder to quantify.

One reason, Bareilles later explained to the Outpost, might be that the stakes rise monumentally from eighth to ninth grade, and students don’t realize it. In K-8, schools for the most part use “social promotion” — boosting students to the next grade whether or not they’ve learned the material — with the belief that keeping students with their peer group is more beneficial for them than holding them back. “Kids come into high school and don’t realize what a unit is,” Bareilles said. “But in high school, if you don’t get the units, you don’t get to stay.”

Finding a way to help students transition from middle to high school is something the district has been brainstorming for a while now, and so the hope is that this semester’s Acorn class will be the pilot of a long-term, expanded program. Bareilles has already submitted a state grant that, if awarded, would fund Acorn classrooms to operate in Arcata, McKinleyville, Hoopa and Del Norte starting in August.

“My hope is within a few years we’re able to have these classes serving 15 percent of our freshmen and keeping them in our comprehensive high schools, where they can take advantage of all the enrichment opportunities, all the career technical opportunities, all the sports and other things that make school a richer experience,” Bareilles said.

With unit loss on the rise in other grades as well, NoHum is also planning a summer school opportunity for other students who need to make units in order to graduate on time.

CLICK TO MANAGE