When white people

aspire to get points for consciousness, they walk right into the

cross hairs between allyship and appropriation…Wokeness has

currency, but it’s all too easy to spend it.

— Amanda Hess, NYT Sunday Magazine, 4/24/16

###

I was introduced to the idea of “woke,” if not the word, in 1962. As an engineering student at the University of London, I loved our weekly Student Union meeting, at which topics affecting us all were debated. The issue in question was whether to extend an invitation to Max Mosley to speak to us. Max is the son of the leader of the British Fascist leader Oswald Mosley, whose “Blackshirts” had rampaged through the East End of London on anti-Semitic race riots, smashing Jewish shop windows and terrorizing black immigrants. At the time, Max supported his dad’s views (he later quit politics to become a racing driver), and the question before our Union was, Should we give someone of his ilk a platform?

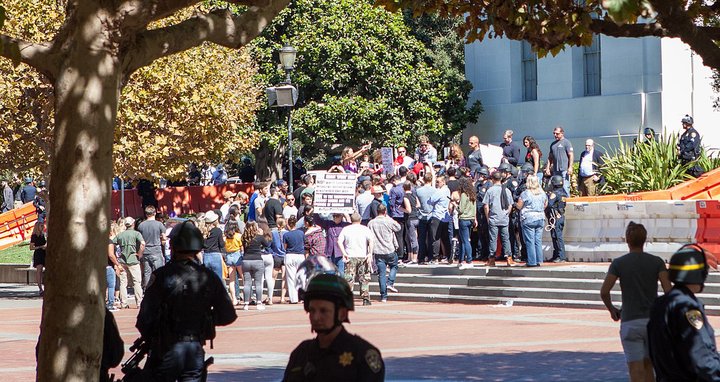

This scenario has played out countless times in colleges across the US, where students clash over whether, for instance, the well-known racist-misogynist Milo Yiannopoulos should be permitted to address students at Berkeley. He eventually did, after bitter debates, but was drowned out by protesters. As I understand it, wokeness won the day.

Milo Yiannopoulos greeting supporters on the steps of Sproul Hall, UC Berkeley, 24 September 2017. (Pax Ahimsa Gethen, Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons)

So, “woke.” The word seems to have come to public attention with the BLM protests about seven years ago, although it’s been around for a lot longer – probably the controversial Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey was the first to popularize it. While the word seems to have started off with the best of intentions – “Alert to injustice in society, especially racism” (Oxford Languages), it seems to have morphed into a term of derision – too much wokeness and you’re virtue signaling. That’s if you’re white – I hope non-whites will respond in the comments. The problem is summed up by what been happening at the venerable New York Times, starting in August 2016. You can read about it here, but briefly:

In August 2016, during the penultimate presidential election, NYT “writer-at-large,” Jim Rutenberg, changed the rules in a front-page story. “If you view a Trump presidency as something that is potentially dangerous, then your reporting is going to reflect that.” News media analyst Martin Gurri, commenting on this, wrote, “Once objectivity was sacrificed, an immense field of subjective possibilities presented themselves. A vision of the journalist as arbiter of racial justice would soon divide the generations inside the New York Times newsroom.” Thus, according to Gurri’s storyline, began the paper’s slide into what he calls “post-journalism,” from journalism-as-fact to journalism-as-opinion; the opinion, in this case, being the one that supports the liberal struggle against injustice.

This change of focus came to a head with the Times’ publication, on June 3, 2020, of an ultra-right op-ed by Arkansas Senator Tom Cotton, “Send in the Troops,” in which he recommended harsh measures against BLM protesters. The backlash by many of the Times staff has apparently, resulted in a change of editorial policy, from facts to woke, not to mention the resignation of its editorial page director, James Bennet. (Why not bring back the Fairness Doctrine, in which opinion pieces that promote extreme POV’s are balanced with op-eds from the “other side, I wonder?)

The Times has, of course, always had a liberal tilt, but until a few years ago, it was a moderate bias compared to, say, HuffPost on the left and Breitbart on the right. (Although its months-long vendetta against Hillary Clinton and her private emails seemed to align with Trumpist propaganda at the time.) What I used to appreciate about it was, in essence, the Times’ willingness to trust its readers by publishing the facts, letting us decide what to make of them. Seems to me, no longer: now we’re protected against illiberal commentary because, I guess, we’re too vulnerable to think for ourselves. The Times is now woke.

Which pisses me off, just as denying Yiannopoulos a platform to express his offensive views infantilizes students: being offended by what someone says isn’t a valid reason to deny their right to say it. (As Stephen Fry succinctly put it, “You’re offended by what I’m saying? So fucking what?”) If students are going to be protected against weird and hateful opinions at university, how the hell are they going to manage out in the real world? IMHO, they should be welcoming any opportunities to hear, debate and agree or disagree with any points of view, no matter how outlandish or offensive. This is how we learn to discriminate, to separate the wheat from the chaff, to think skeptically, and to understand the dangers of confirmation bias. In short, to be adults.

In 1962, I voted against inviting Max Mosley to speak to us, because, I suppose, I thought that was the “woke” thing to do, had I known the word then. Today I would vote the other way: denying free speech is the enemy of democracy, and only encourages those whose views I object to. And yes, I am a card-carrying member of the ACLU.

CLICK TO MANAGE